The Numbers Behind MLB's Home Run Surge

Maybe it was the one-handed, one-legged home run hit by Todd Frazier of the Mets. Maybe it was Ketel Marte of the Diamondbacks hitting a home run 482 feet. Maybe it was Arizona and Philadelphia smashing a record 13 home runs on Monday, or the Nationals going back-to-back-to-back-to-back Sunday. Maybe it was Eugenio Suarez hitting a home run with an exit velocity of just 86.7 mph.

Chances are you have reached a tipping point when it comes to the way the ball is flying out of ballparks this year. And because we are conditioned to explain changes in our world by yelling “Conspiracy!” in a Pavlovian way, we are flooded with conclusions that the baseball is “a joke” and that owners secretly “juiced” the ball to jolt declining attendance.

Now that such theories are so widespread, individual events and games are loaded with “confirmation bias.” We believe the ball is juiced, and so every opposite field homer is proof that it is.

What’s actually going on? Setting aside conspiracy theories, these are the facts:

• The ball is flying more than it did last year. However, it is not quite flying like it did in 2017, when the conspiracies began (with some good reason).

• Hitters are hitting the ball harder and in the air more than ever before.

We have to be go beyond the simplicity of the “juiced ball” theory and take a hard look at how hitting has changed and will continue to change. Hitting has lagged behind pitching when it comes to leveraging science and technology, but that is beginning to change, which I wrote about before the season started.

Marte, for instance, is just one of many hitters who have crossed this Rubicon. From 2015–17 he hit eight home runs and slugged .361. He swung the bat like an old-school middle infielder: quick to and through the ball with a strong top hand and a short, low finish. Now at 6'1", 165 pounds, he swings like Jim Thome: the bat is in the zone longer, he extends fully through contact with his arms extended to a high finish that creates so much loft he often winds up on the heel of his front foot, with his toes off the ground, the way that Thome back-legged home runs. He has learned to create speed and leverage—to hit the ball better and higher, not more often.

Over the past two years Marte has hit 30 homers and slugged .467. His launch angle increased from 5.7 degrees last year to 11.3 this year. His exit velocity improved from 88.5 mph to 91.0 mph.

There are stories like his in every clubhouse. This is how you win (it’s too hard to stitch three hits together to score) and this is how you get paid. Yes, strikeouts keep going up, but when hitters swing now they swing for maximum damage. It’s increasingly a boom-or-bust game.

So let’s set aside conspiracy theories and stick to the facts. Here is what is going on:

1. Baseball is on a record pace of home runs

At this rate, MLB hitters will break the record of 6,105 home runs set in 2017 not by a little, but by a lot: by 456 homers, or 7.5%. Compared to last year, homers are up 17.5%, with almost one thousand more dingers expected. The 2017 season was so home-run happy that to help stem the conspiracy theories MLB commissioned an independent study to examine the baseball. The panel found that while the physical properties of the baseball appeared to be unchanged, the ball did create less drag as it moved through the air. Less drag equals more distance. More distance means more home runs. It wasn’t your imagination. The ball played “hotter.” In 2018, home runs retreated sharply (down 8.5%), but now they are flying again. The whip-saw nature of these major swings—up 8.8% in 2017, down 8.5% in 2018, up 17.5% in 2019—encourages the idea that MLB is messing with the baseball like it’s a thermostat, turning it up or down at will.

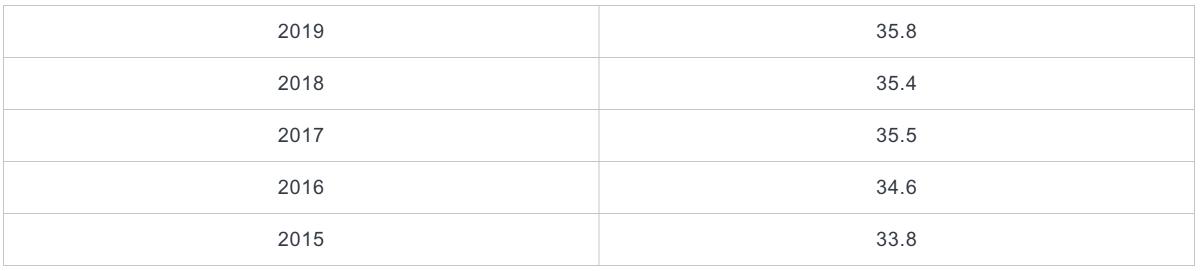

2. Batters are hitting more fly balls

The saying around the game is “slug is in the air.” Nobody wants to hit a groundball. And so we get a record rate of flyballs:

MLB Fly Ball Percentage

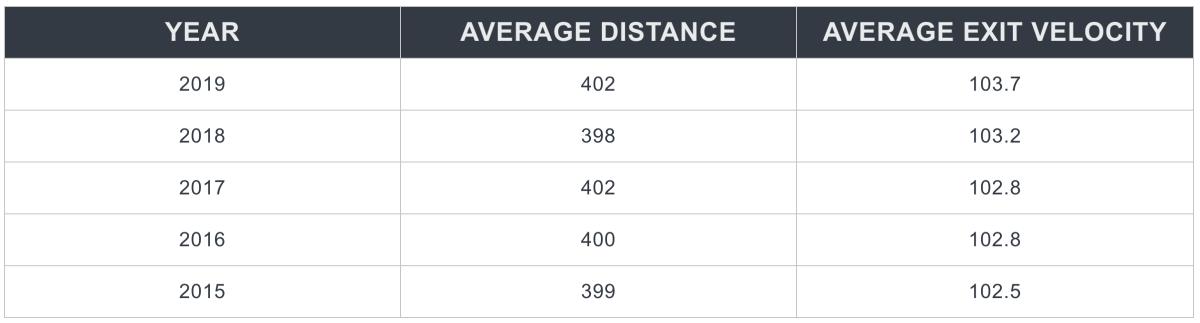

3. Batters are hitting the ball harder

Take a look at this: fly balls that are home runs are being hit harder each year:

Fly Ball Home Runs

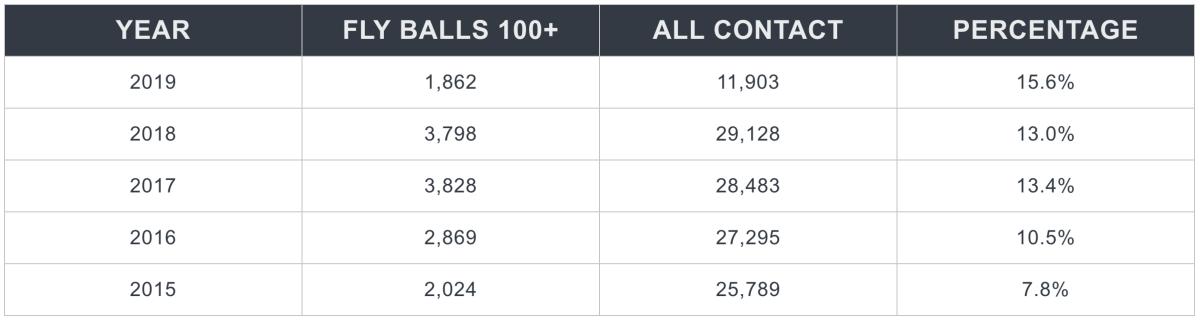

4. More well-hit fly balls are going out of the park

Let’s take all the fly balls hit at least 100 mph. They are occurring this season at double the rate as they did in 2015, which means we have seen almost as many such hard-hit fly balls as we saw the entire 2015 season:

Fly Balls Hit 100+ MPH

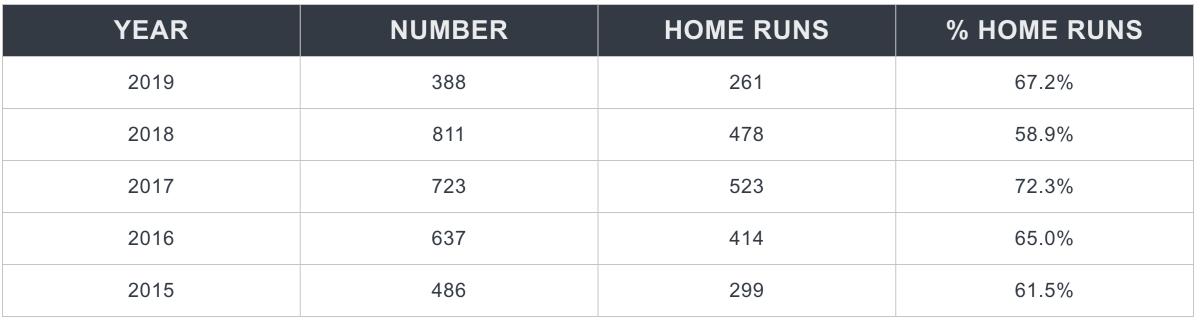

5. The “hotter” baseball—the one with less drag baseball admitted to from 2017—seems to be back

Let’s try an experiment. The average exit velocity of a home run last year was 103.5. So let’s examine what happened to all fly balls hit in the past five seasons at between 103 and 104 mph. The average launch angle for such fly balls in each season happens to be exactly the same in four of those years (30 degrees) and virtually the same in the fifth (31 degrees in 2016).

With fixed coordinates, this experiment is the equivalent of Iron Byron, one of those golf ball testing robots. We can look at how baseballs fly when they are hit at the same exit velocity and the same launch angle:

Fly Balls Hit 103–104 MPH

What does that mean? It means a fly ball hit at those parameters this year is 14% more likely to be a home run this year than it was last year. (But 3% less likely than the same batted ball in 2017.)

3% sounds like a margin of error, subject to differences in weather and schedule. But 14% is a large difference.

So this is the environment that creates more home runs: hitters are learning to hit more fly balls, they are hitting the ball harder (when they do hit it), and the ball is carrying farther this year than it did last year.