The Most Interesting Things I Found On Baseball-Reference Monday Night

There are few institutions that can claim to be as simultaneously frustrating and tremendously boring as the rain delay—the practice of waiting indefinitely for an event that may or may not be continued, stuck in a closed environment, while everything around you is wet and getting wetter. It lacks the high stakes of physical peril or the practicality of waiting in line at the DMV. A rain delay has no true villain to absorb your frustration; instead, it has only the weather, which, as a general concept, is a little too one-dimensional to be a good anti-hero. (What can make a person feel more powerless, more hopelessly and stupidly human than getting angry at the weather?) A rain delay means you’ll get home late. It probably means you’ll be uncomfortable, or at least a little bit chilly. It makes up for this only by offering time to get drunk, or quietly marinate in existential dread, or both, though it isn’t recommended to mix the two.

With a series of rain delays around the league on Monday—first Astros-Reds, then Mets-Braves and, all along, Phillies-Nationals—baseball gave us plenty of time to marinate in this existential dread, or, alternately, to turn to the game’s best antidote for existential dread: Baseball-Reference. The website holds the record of every beautiful and terrible and weird thing that has ever happened in baseball, and the existence of the site is a magical record unto itself. There are not very many places on the internet anymore that feel pure, that feel worthy of losing yourself in. But there is Baseball-Reference. If there’s any better testament to the capacity of human knowledge, I’m not familiar with it. (I know about Encyclopedia Britannica, and I don’t particularly care.) Baseball-Reference is the perfect corrective for a rain delay. Getting lost on Baseball-Reference suggests that time can only be spent, rather than wasted; it’s a reminder of the texture and richness of history, enough to rival the flash of any action in the present. It can be accessed from your pocket. It has so many delightfully weird names from the nineteenth century. It’s perfect.

Here, then, are the best fragments of my journey across Baseball-Reference during the delays on Monday:

1. When did baseball stop nicknaming left-handers “Lefty”? Sure, it’s simple—arguably too simple—but this isn’t necessarily bad, and it’s not as if modern nicknames represent any great improvement here. Simple can be good. There were whole generations of baseball redheads nicknamed “Red.” A lefty will be constantly labeled by his left-handedness, anyway. Why not own it? Go by Lefty! Don’t be a lefty. Be Lefty.

In recent decades, the term has been used only occasionally, as a secondary nickname (à la Steve Carlton), rather than as a primary name. Baseball’s last true Lefty was Lefty Hayden, who appeared in three games in relief for the 1958 Cincinnati Redlegs, across a period of two weeks in midsummer. The 23-year-old’s performance was fine-ish on paper, certainly not great, but far from disastrous—2 runs, 5 hits, 17 batters faced—and yet he never pitched again, at any level of organized ball. The Cincinnati Enquirer wrote that he’d been “coming on like Gang Busters” when he was called up from Triple-A (he was said to have an “All-American curveball”), but there was no note on his disappearance from the roster or, indeed, the game as a whole. Lefty was, apparently, gone, and with him, so was his name. It’s been six decades, and baseball has not seen a single man since go by Lefty.

Eugene “Lefty” Hayden died in Lodi, California, in 2003, nearly half a century after his summer in Cincinnati. The Lodi News-Sentinel included the time and place of his funeral in a daily listing, but there was no obituary.

The last Lefty is gone. Bring back the Lefty.

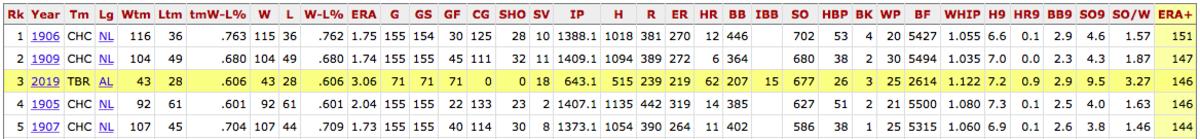

2. The 2019 Tampa Bay Rays’ place among baseball’s best pitching teams is terrifying and, frankly, ridiculous:

But the most important piece of this leaderboard is not pictured here. No, the most important piece of this leaderboard is that the 1906 Chicago Cubs—the most dominant pitching staff in history, by ERA+—had a pitcher named Orval Overall, a man whose parents presumably looked at him as a child and thought, “Ah, Orville Overall, a wonderful name for our darling boy, if only we could get Orville to look more like Overall.” (Orval went on to lead baseball in strikeouts in 1909, and eventually to become the manager of the Security First National Bank in Fresno and a director of the California State Automobile Association. The 2019 Rays can only hope!)

3. There’ve been 17 players nicknamed “Babe,” yet only one nicknamed “Baby”—Baby Ortiz, who somehow played 50 years before Big Papi Ortiz.

(“Baby Doll” Jacobson gets half credit here.)

4. In a Monday game that was not delayed by rain, Mike Trout hit his 20th home run of the year, guaranteeing him an eighth consecutive season with at least 20 HRs. (Of course, these eight consecutive seasons have also been the first eight seasons of his career.) By now, Mike Trout Fun Facts are a genre of baseball information unto themselves, so common and so commonly extreme that they feel beyond parody, a spiritual cousin to those Chuck Norris jokes that were weirdly popular in 2007. (“Mike Trout’s house has no doors, only walls that he walks through.”)

Welcome to the 2019 20 HR club, Mike Trout!

— FOX Sports: MLB (@MLBONFOX) June 18, 2019

That's 8 straight such seasons for Trout, nbd.

(via @Angels) pic.twitter.com/XLWz08aTSH

And, yet, there are still so many insane fun facts about Mike Trout! They’re still fun. At this point, we have no reason to disbelieve any of them, but they still all feel a little unbelievable.

So: Eight 20-HR seasons is a career’s worth. Edgar Martinez retired with eight. Larry Walker. Carl Yastrzemski. It’s only half of Alex Rodriguez’s or Babe Ruth’s 16, of course, and nowhere near Hank Aaron’s record 20—but it’s enough to fill a baseball lifetime, one fit for the Hall of Fame, even. And Mike Trout’s already there, at 27, perhaps only just entering his prime as a hitter. He’s already there (!).

5. Right now, as of tonight, baseball has seen 19,232 players; 1,971,904 runs; 306,601 stolen bases; 518,577 errors; and 387,206 double plays. These have combined for infinite heartbreaks and disappointments and moments of grace and minor consolations and first loves.

Tomorrow, all of these numbers will change. They’ll keep changing, and, with any luck, they’ll never stop.