Jon Peters and the Pain of Being 'SUPERKID'

Sports Illustrated’s annual “Where Are They Now?” issue catches up with the stars and prominent figures from yesteryear—past features have included Sammy Sosa, Brett Favre, Dennis Rodman, Tony Hawk and Don King. The 2019 issue features an inside look into the new life of Alex Rodriguez, Yao Ming’s mission for Chinese basketball and more.

For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

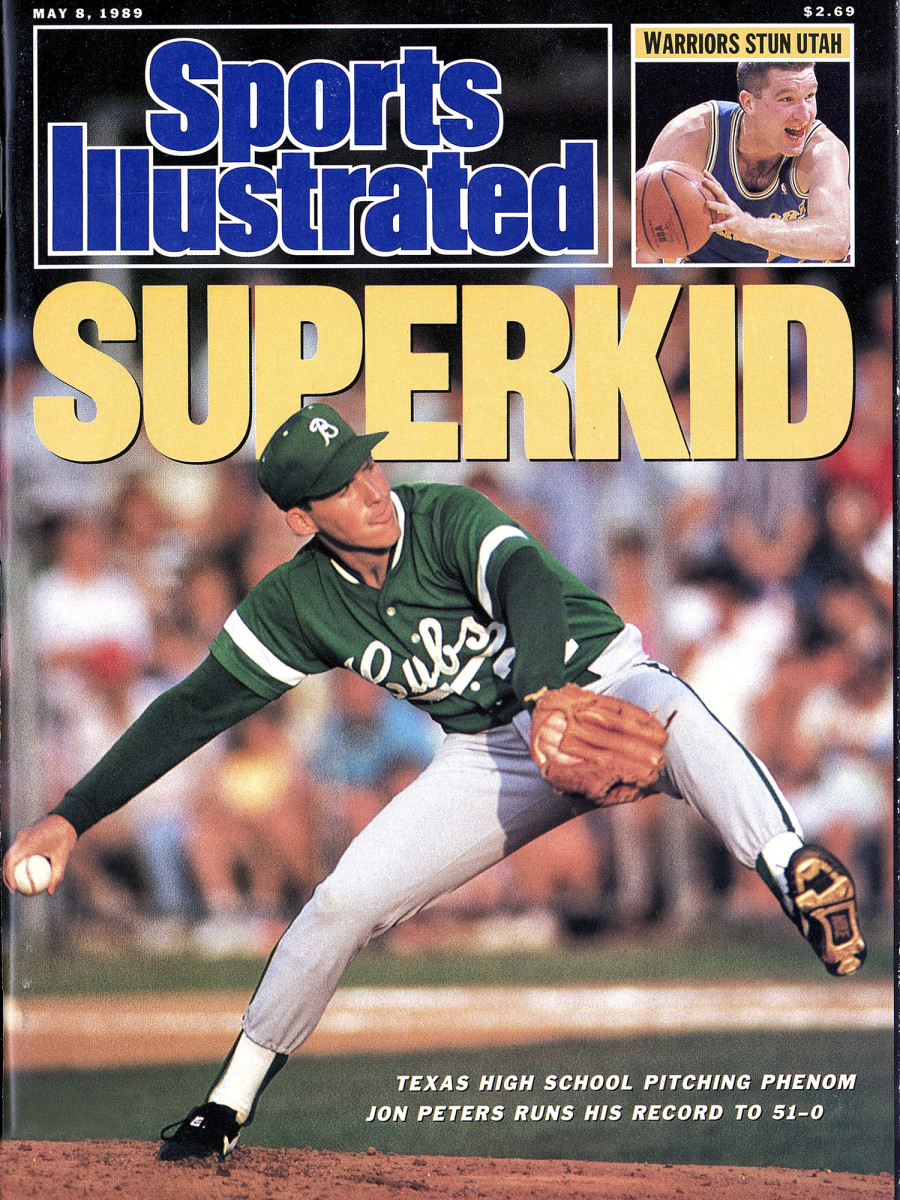

There he is on the cover of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, 30 years ago last spring: May 8, 1989. He is on a pitcher's mound, rearing back with a baseball in his right hand, his left foot in the air, his pink face bathed in sunlight beneath the green cap of Brenham High. His tongue is squeezed between his lips. Above his head, a single word in yellow capital letters: SUPERKID. Never before had a high school baseball player been featured on the cover of SI. The story inside opens with a photo spread in which he stands solemnly on that same mound, turned toward centerfield with his hat held over his heart during the playing of the national anthem, his eyes cast downward. Behind him, the school band members in their white polos, and beyond them a sea of blurry faces in the grandstand behind home plate. The headline: AN AMERICAN CLASSIC.

There are certain kinds of irresistible sports stories. One involves a small town uncorrupted by the march of time and a player or team unspoiled by money or fame or drugs. It is a story that subliminally (or loudly) purports to travel across generations to an era when athletes were heroes and sports were an oasis of purity, a time that never existed but which we are forever seeking to rediscover. In the spring of 1989, Brenham, Texas, was that place and Jon Peters was that athlete.

The story reached its climax on the evening of Friday, April 28, at Fireman's Park in Brenham, a town of 11,000 residents 75 miles northwest of Houston (and the home of Blue Bell Ice Cream, a detail that made its way into all the stories about Peters, including the one you're reading right now). More than 5,000 spectators squeezed into a stadium that seats 1,200, while in the parking lot half a dozen satellite trucks provided news coverage. SI sent Rick Reilly, then the best-known writer at the magazine, to watch Peters try to set a national record with his 51st consecutive victory. Reilly got right into the throwback spirit:

"There is a real baseball legend in this country and he's not Robert Redford or Kevin Costner. This legend is 18 years old, shaves twice a week and just had a big fight with his best girl. His name is Jon Peters and he's from Brenham, Texas."

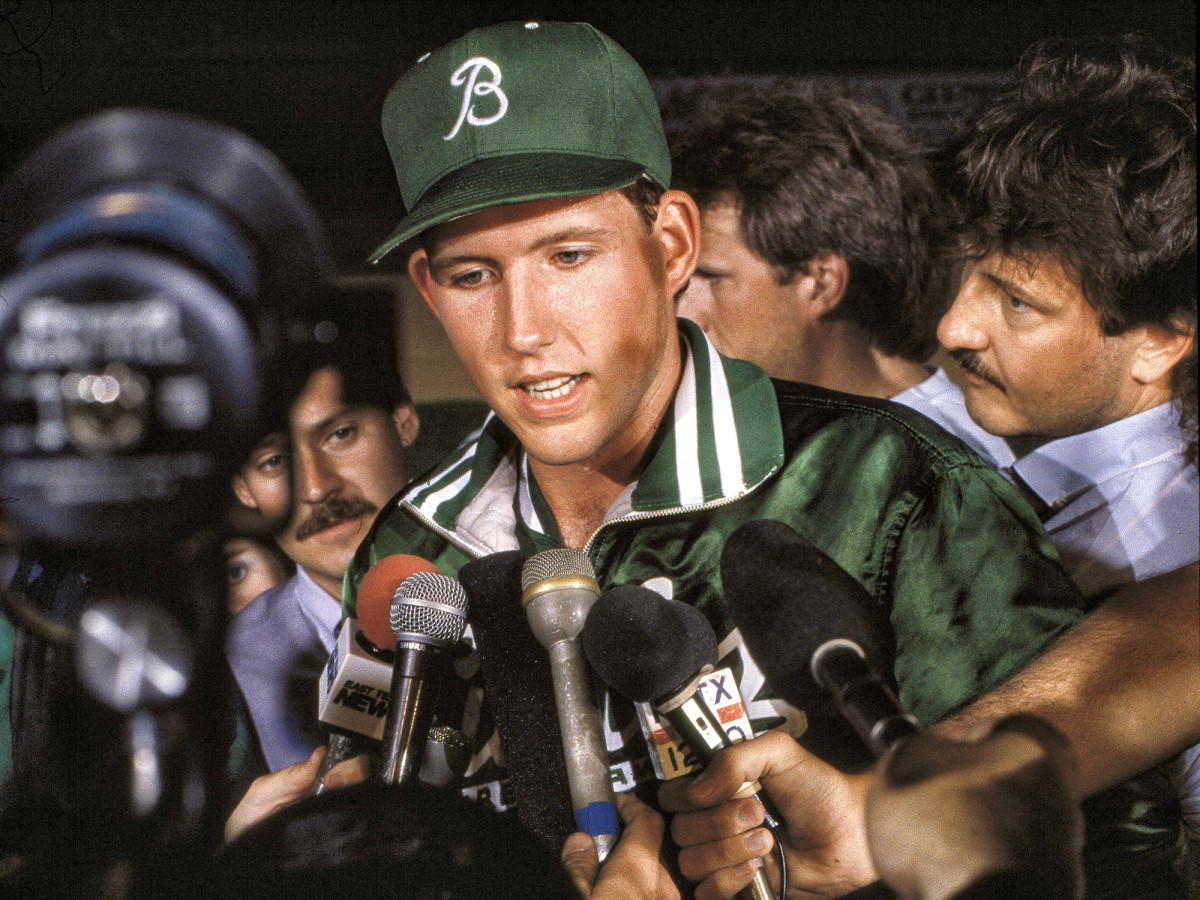

Peters was a relative unknown in 1989, ripe for discovery by the media. (Such a revelation would be impossible in 2019, when his feats would have gone viral.) Peters played his part perfectly that night. He threw a 12-strikeout no-hitter and in the fifth inning stroked a single to right for the run that gave the Brenham Cubs a 10-0 mercy-rule victory over Snyder High. He rode off the field in twilight on the shoulders of his teammates. He was surrounded by cameras and notebooks and provided just the right quotes. "Never in my wildest dreams," he said, "did I think I'd make it to this record."

There was nothing wrong with this tale, as far as it went. It was just incomplete. The fans in attendance, the reporters covering the event could not have known that not only was this the best day of Peters's young life, but it was also the worst. They couldn't have known that Superkid was in fact a bundle of adolescent insecurity and anger, dating to when he was first nicknamed Big Pete and had to wear an adultsized Little League uniform that looked different from his teammates'. Or that on the eve of the record-setting game, Peters says he swallowed three-quarters of a bottle of Tylenol, one tablet at time, in an attempt to end his own life. "Just wanted it to be all done," he says now. "I felt like everybody's lives would be better without me." He woke up the next morning very much alive, with a fierce ringing in his ears.

They couldn't have known that Jon Peters, the athlete, had peaked two years earlier, when his fastball reached 92 mph in winning the Class 4A state championship game. "At that point Jon Peters was a top-five-rounds draft choice, I'm sure," says Lee Driggers, who coached Peters's first two years in high school after discovering him as a seventh-grader. Shoulder surgery in the summer after his sophomore year dropped Peters's heater into the low 80s and prompted mechanical changes that led to three more operations by age 21. Through two high school seasons and the final 23 of his 51 record-setting wins, he got hitters out with a funky delivery, mixing guile and control with just enough speed. Peters had accepted a scholarship to Texas A&M, but there was still talk that he would go straight to professional baseball. In fact, that was no longer a practical option. Scott Nethery was a 29-year-old with the Major League Scouting Bureau when he saw Peters pitch in high school. "His delivery was real unbalanced, and with a fair amount of effort," says Nethery, who would later become friends with Peters. "I told people, 'He's gonna get hurt.' I just didn't see him as a pro prospect."

They couldn't have known that Peters would walk out of Fireman's Park that night and into more than 20 years of adulthood spent battling physical pain, depression and alcoholism, a divorced father of two children whose life was slipping away.

Three decades have passed. It is a late-spring afternoon in southeast Texas, where a restless, warm breeze promises the summer heat to come and a gray sky portends the dangerous thunderstorms that will follow. Much has changed since Peters's big night. The population of metropolitan Houston has nearly doubled to seven million; Brenham has grown to almost 17,000, some of them moving from Houston in search of space and tranquility. Blue Bell has recovered from a 2015 health-scare shutdown, and Peters's old high school has been replaced with an updated facility. Two other high schoolers, Bryce Harper and Hunter Greene, have appeared on the cover of SI since. (Also, 2010 Heisman Trophy winner and NFL quarterback Cam Newton restarted his career at Blinn Junior College, which is in Brenham.)

Yet Fireman's Park seems nearly frozen in time, from the green, wooden grandstand to the tall oaks beyond the outfield fence to the railroad tracks at the top of a grassy berm, freight trains rolling past at all times of the day and night. As ever, an iron gate in the shape of a baseball diamond provides entry to the field. Other than a giant baseball-shaped sign on the outfield fence that displays Peters's name and number 21, it is as if, in this place, time has stood still. Peters's life experience, however, is a reminder that it never does.

Earlier in the day I had met Peters, 48, in Houston, where he lives with his wife, Lauren, not far from his two children and ex-wife, and we drove the 75 minutes to Brenham. Along the way, Peters narrated the years before and after his big night in '89, the former a road map to the anguish that gripped him in high school, the latter a long, hard climb to physical and mental health. He is almost nine years sober now, since Sept. 7, 2010, his 40th birthday. He works in business development for an oil and gas company but hopes to build a career as a public speaker, telling others the story of his life and his faith, which he has done on several occasions, including in a 2018 memoir, When Life Grabs You by the Baseballs.

It is the great paradox of Peters's life that the one thing he loved best and excelled at most became the vehicle by which his demons found him. Not that he blames baseball. He doesn't blame anybody or anything, including the media that made him a 15-minute celebrity when he was not prepared for it. "I was the fool that kept all my problems to myself," he says. "If I would have shared with somebody, who knows what would have happened? It wasn't a miserable experience, I was just miserable inside." The son of Valgene, a math professor, and Ruth, a former college softball player who was Jon's first battery mate, Peters grew up outside Brenham in a ranch house on a dead-end street that was renamed Pitcher's Lane in 1989. Jon had an older brother, Ronnie. The family owned 20 acres and every year kept a few cows for slaughter. Jon and his buddies would fish in nearby ponds, which they called honey holes. Jon grew quickly into a tall and pudgy boy, painfully self-conscious. "That was a big thing to me, feeling fat all the time," says Peters. "Even today, sometimes I feel fat." (Peters is 6'2" and 200 pounds, certainly not fat by any obvious measure).

But even in his awkward youth, baseball discovered him. The Cubs have a proud tradition, with seven state high school titles and numerous homegrown pros. "I grew up watching Brenham play," says Peters. "Then I found out I was pretty good at throwing. And I liked it." His first sip of fame came at age 12, when he struck out all 18 opponents in a Little League all-star game. Some family friends two hours away in San Antonio saw his name in the local paper, though the story was picked up nationwide. It was the beginning. "Here in Brenham, Jon Peters was always a big deal," says Kris Krause, who grew up with Peters and was the bullpen catcher in their high school team (and later a football player at Blinn). "He was Big Pete."

When Peters reached seventh grade, nearly fully grown, he met Driggers, who was in his first year as Cubs coach. Driggers made Peters the varsity team manager and offered him guidance on getting ready for his high school career. Peters embraced the challenge. "Jon was a pleaser," says Driggers.

Matt Fisher, a high school teammate, says, "Jon was relentless in the work he put into baseball. I mean, it was nonstop with Jon." John Schulte, another high school teammate and later a third-round draft choice of the Pirates, says, "Jon worked harder than anybody on the team. He would run five miles every morning to stay in shape."

The benefits came quickly: Peters went 13-0 as a freshman and 15-0 as a sophomore, and Brenham won the state title both years. Along with 92-mph heat he had command of three pitches: fastball, curve and changeup. "Jon was a pitcher, not a thrower," says Driggers. "He could spot his fastball anywhere, and he could throw a curveball anywhere in the count. Those are things most kids his age could not do."

In the summer of 1987, after Peters's sophomore year, he was invited to Junior Olympic tryouts in Raleigh. His right arm was already prone to soreness when he made his first relief stint in Raleigh. "As I wound up and released the ball toward my catcher," Peters writes in his book, "my arm felt as though it snapped off and went with the throw." Back in Texas he underwent arthroscopic surgery to repair a tear in the anterior capsule (a group of ligaments) in his shoulder. He would never throw as hard again, though it scarcely constrained him. Owing to the unreliability of certain high school records, he first "broke" the mark for consecutive wins with his 34th straight on April 12, 1988, surpassing a record that was believed to have been set 11 years earlier. SI covered that one, too, with a story by SI senior writer E.M. Swift, who ended his piece: "If you like trains and you like baseball and you like the sweet smell of honeysuckle growing wild along the embankment, you should take in a game at Fireman's Park this spring when Jon Peters is pitching. When he is 17. It is a very good time, and he will remember it for the rest of his life."

Soon it was discovered that a high school kid in 1980 in McColl, S.C., had won 50 straight, so for Peters, the chase began anew, and it brought him back to Fireman's Park on the night of April 28, 1989. There were more cameras, more reporters and more attention than the last time. Reilly's story hinted at Peters's discomfort, quoting him about the fight with his girlfriend: "I swear," said Peters the night before the game, "if I had an ulcer, it'd be fixin' to bust."

But even these nuggets are presented as minor impediments to an unfolding slice of Americana, the fuzzy-cheeked hero with requisite nerves, straight out of central casting. Fair enough. Peters never told anybody how bad he felt. Never told anybody about the suicide attempt until years later. Never told anybody about his crippling insecurity and the temper tantrums that only his family saw. Never told anybody what he thought as the attention built: I'm a fake. I'm a loser. Everybody is laughing at me. "To the outside world I was this all-American guy," he says now. "I was thinking, I'm not this all-American guy at all. I've got you all fooled."

Now Peters is standing outside Fireman's Park, after three decades have passed. I ask him about that night. He turns and points at the parking lot. "We would get dressed in our uniforms at home, and then drive and park right over there," he says. "I had a Cutlass Supreme. Oldsmobile. That night I pulled in and there was a security guard at the gate, and I mean, it was just packed, way before the game. ABC, NBC, ESPN. I got out of the car and I just pulled my hat way down low." Peters stops talking, clearly troubled. He begins again and his voice catches in the back of his throat, a grown man in a golf shirt, khakis and loafers, reliving 30-year-old pain. "I was so scared," he ways. "I was hoping maybe nobody would recognize me."

Peters wipes his eyes and takes a deep breath. He nods toward the gate. "Once I got through there and got out on the field, I was in another place," he says. "That's the way it always was with me, back then. On the field, I was like, Let's just stay out here as long as we can." When the game was over, the celebration finished and the interviews done, Peters climbed into his Olds with his girlfriend, patched things up for the time being and went home.

Though he finished at Brenham with a 54-1 record, there would never be another big baseball moment for Peters. He accepted the scholarship to A&M but needed elbow surgery as a freshman. He transferred to Blinn and moved back home, but things did not get better. Tommy John surgery in the spring of 1991 and, a year later, rotator cuff repair. Three years after he became Superkid, Peters had the damaged right arm of a very old man. He had also started drinking, and would keep drinking. First beer, then wine and vodka. Through a seven-year marriage and a divorce, through the birth of his two children (Kylie, now 15, and Jake, 12), through at least five jobs.

By the spring of 2010, a few months after his divorce, Peters was going through two 1.75-liter plastic bottles of vodka every day, almost entirely alone. He would keep one bottle in his truck. "I was a maniac," says Peters. "Just killing it every day." One night Peters called his boss at the time, Wes Weatherred, and told him he couldn't stop drinking and wanted to die. Weatherred rushed to Peters's apartment. Shortly after that, Peters did a 28-day residential rehab stint. "Didn't stick," he says. In September he flew to Georgia for another one. That one has stuck for nearly nine years, and along that same journey he has embraced his faith in God for strength and guidance.

In 2014 he shared every bit of his story in a talk at East Texas Baptist University, where Driggers had been baseball coach. He expected a handful of students to attend; there were hundreds. Afterward, Peters recalls, a young man "came up to me and said, 'When I came into the room today, I wanted to die. I never felt like I fit in. I don't feel like I'm worthy. Now I don't want to die anymore.'" When Peters's book was published last year, it shocked many of his old friends, who had little notion of his struggles. "Jon wasn't the kind of guy to ask for help," says Fisher. "But man, everybody has demons. I hope he's got 'em whipped. He's a great guy and he's got our support."

Back at Fireman's Park, the sky grows darker and the wind gusts up from the west. Peters goes back again to that time and that night. "It should have been the time of my life," he says. He also appreciates better than most that life, happiness and sobriety are dispensed one day at a time, and no more. He is happy today, and with a vision. "Maybe when I'm gone, people will say, 'Oh, he's got that record,'" says Peters. "But maybe they'll say, 'That guy struggled, and he was real and helped people.'" The ballpark is empty, the grass pristine and the dirt smooth. Up on the hillside, a freight train clacks into view, blasts its whistle three times and then rolls toward a distant horizon.