Moon Magic: The Apollo 11 Landing Wasn't the Only Fantastical Event of July 20, 1969

This story appears in the July 15, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price.Click here for more.

"If you want to know what aspect of the moon landing was discussed most in the bullpen it was the sex lives of the astronauts. We thought it a terrible arrangement that they should go three weeks or more without any sex life. Gelnar said that if those scientists were really on the ball. . . ."

—Jim Bouton, Ball Four

Back when former PGA golfer Chris Perry was a kid, the world could pretty much be divided up into sun people and moon people. Sun “worshippers” embraced the outdoors and sported permatans; moon people were flaky night owls, happiest cavorting in a cool lunar light. As one who spent his youth striding fairways, Perry, 57, figured to be the former. Yet it’s not even close: On clear nights he can still find himself full-on moonstruck, stirred nearly to tears by wonder, awe and 50 years of persistent connections that he can’t begin to explain.

“It just goes on and on and on,” Perry says. “What are the odds? Give me a lottery ticket. It’s bizarre.”

Moon love these days is hardly rare, of course. Rising temperatures, not to mention drought and skin cancer fears, have seriously dented the sun’s image; meanwhile, nothing recharges a romance like a nice, round anniversary. Fifty years ago, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to land on the moon. Commemorations have been under way for months now and are sure to last deep into fall. The first reason is because it remains a spectacular human achievement. The second is because of the 1969 Amazin’ Mets.

Pairing the moon landing with the hapless franchise’s first, and most unlikely, World Series title has long been a thing—if only because of context. In an era scarred by race riots, assassinations and the cultural earthquake of the Vietnam War, both events registered as against-all-odds triumphs, examples of the species at its lovable best, never mind the carping of Cubs fans. That Mets players, watching Armstrong’s moonwalk that night in a Montreal airport bar, tipsily declared themselves moon people only helped.

“We all sat there in disbelief that something like that could happen,” Mets ace Tom Seaver later recalled. “And you talk about metaphors: I mean, we just looked at each other and said, you know, ‘Why not?’ ”

Still, it should be noted that any inspiration was slow-acting; on that momentous day the second-place Mets, four games behind Chicago, began a free fall that, by Aug. 13, had them 10 back. No, for a more immediate sense of impact, you have to shift 3,000 miles west and seven years earlier, when the Perry family began a relationship with the moon that proved far more personal and, well, cosmic than any “miracle” in Flushing Meadows.

Sources differ—it was either 1962 or ’63, in the Giants’ dugout at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park or Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Chris’s uncle, future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry, was taking batting practice when a Giants beat writer named, yes, Harry Jupiter called out to manager Alvin Dark that the young pitcher looked like he had some pop.

To which the equally aptly named Dark replied, “No way. There’ll be a man on the moon before Gaylord Perry hits a home run.”

So it happened: At 1:17 p.m., during Gaylord’s shaky first inning against the Los Angeles Dodgers, the announcement came at Candlestick that Apollo 11 had touched down. A moment of silence ensued. Something changed. Perry, who had already given up three runs, surrendered none over the next eight innings to earn the win; more whimsically, 34 minutes after the announcement he fulfilled, as one wag put it, “Dark’s aside of the moon” by belting—in his 485th major league at bat—Claude Osteen’s high fastball through a biting wind for his first career home run.

“It’s all true,” Osteen says. “But I certainly wasn’t watching him run around the bases. Anybody that says that they enjoy giving up a home run is crazy—especially to a pitcher. It was embarrassing for me.”

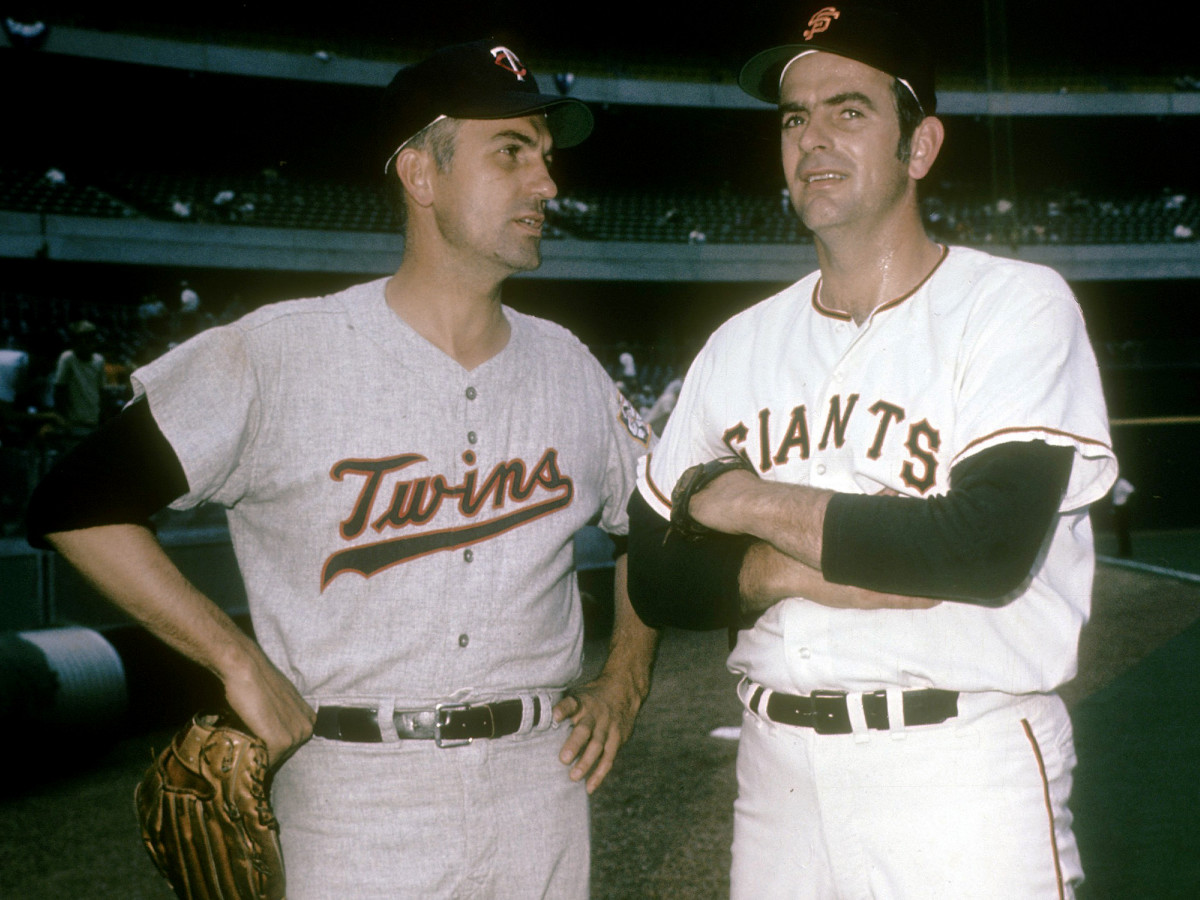

Meanwhile, up in Seattle, Gaylord’s older brother, Minnesota Twins pitcher Jim Perry, was at work on his own rarity. First, he threw two shutout innings—and doubled and scored the game-winning run on a bases-loaded balk by Pilots pitcher John Gelnar—to finish an 18-inning game continued from the night before. Then, after missing the televised landing because he was out warming up, Jim threw nine more shutout innings to—again—beat Gelnar for his second win of the day.

“I’d have liked to have seen the guy set down on the moon,” Jim says. “But I said, ‘I’ll see it tonight on the news. I can’t help him. I’ve got to get my stuff together for the next game out there.’ ”

That should’ve ended all galactic ties, with the nifty postscript that, in the 1975 trade that sent him spinning into retirement, Jim was shipped to Oakland for—yes—John (Blue Moon) Odom. But on Aug. 17, 1985, Jim’s son, Chris, married college sweetheart Kathy Solacoff—and there, at the reception held at Elk’s Lodge #83 in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, stood one of his new father-in-law’s childhood friends: Neil Armstrong. So it was that Jim and Gaylord Perry, a pair of sharecropper’s sons from Williamston, N.C., seized their chance to tell the first man on the moon that, back in July of ’69, they’d had a big day, too.

“Oh, he was glad to hear it,” Jim says of Armstrong. “He said, ‘That’s great: Something else happened good. . . .’ I said, ‘That’s right. You were just about out of this world, you had all these machines, but you just push buttons! I couldn’t do that. I’m in the world here, and I had to do it myself.’ We had a good conversation.”

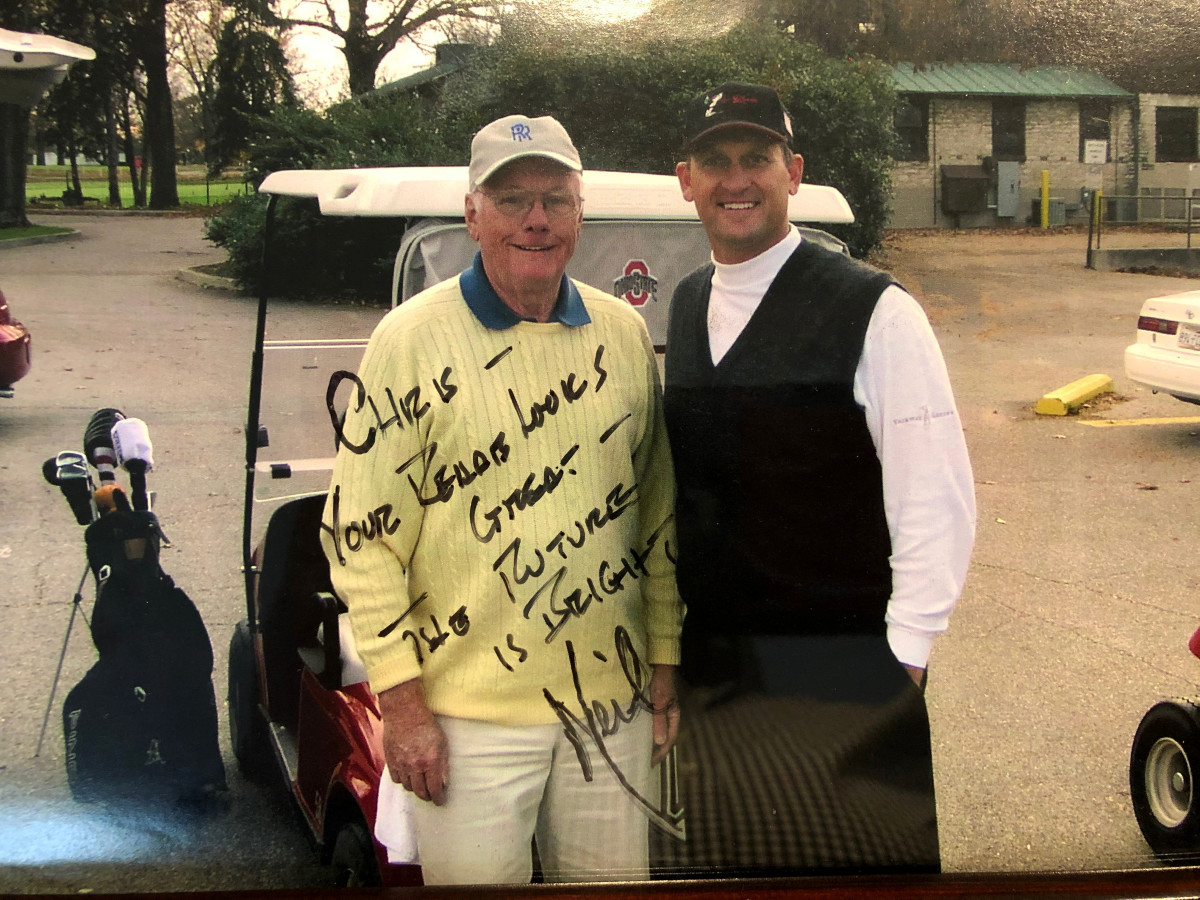

Every so often, in ensuing years, the Perrys and Armstrong would have another casual encounter: Chris played golf with him a few times, and in 2001 the astronaut stopped by Chris’s home in Ohio. Chris and Kathy’s unsuspecting five-year-old, Emily, took her grandpa’s friend by the hand for a tour, showed him a closet, a dead bug, her books—one that happened to be about . . . Apollo 11. “Oh,” she said finally, “your name is Neil Armstrong, too, isn’t it?”

But childlike wonder can’t last forever, especially in adults. Though they won a state high school baseball title together, became the only brothers to win the Cy Young Award, combined to win 45 games with the Indians in 1974–75 and today live in the same state, Jim, 83 and Gaylord, 80, have recently had what the family calls “differences.” At some point a squabble between the two escalated—Jim won’t talk about why, and Gaylord declined an interview request—and now, Jim says, “I haven’t talked to Gaylord for a couple years. He goes his way, and I go my way.”

“It’s kind of sad,” Chris says. “I’ve just stayed out of it.”

But maybe there’s one last bit of moon magic for the Perrys. Chris says that, come the 50th anniversary, he’s going to urge his father to phone Gaylord, to revel in what they did together. And to a reporter, at least, Jim doesn’t seem averse. “I might do that, July the 20th,” he says. Then, after a pause, he adds, “When’s this coming out? Make sure to send me four, five copies because I might give Gaylord one. You know, send it to him?”