What Made Roy Fly

Twenty months after Roy Halladay’s plane went down, Roy Halladay’s plane goes up. Roy III—Roy the son, Roy the Hall of Fame pitcher—is dead. Roy Jr.—Roy the father, Roy the commercial pilot—is blinking into the sunlight on a small private airfield outside Denver.

He hoists himself into the cockpit and smooths his headset over his Blue Jays cap. He runs through his preflight checklist and taxis out to intersection Bravo.

“Tower,” he radios. “Chipmunk one-nine-five-six Delta is ready on one-two left.”

Roy III never flew in this plane, a two-seat, single-engine de Havilland Canada DHC-1 Chipmunk. Roy Jr. bought it in March 2018, six months after his son’s body was recovered from the wreckage of his own plane, an Icon A5.

He would have loved it, the father muses wistfully. He was always so good at flying tail-wheelers, which require more skill to land than nose-wheelers. Roy Jr.’s profession is also his passion: He also owns half a dozen antique small aircraft, which he rotates regularly. Every time he restores one, he sells it, then goes in search of a new project.

He was back in the air a day or two after his son’s crash. He doesn’t even remember that first trip. He had errands to run, or people to visit, or something. So he went out behind his house to his little runway and climbed into his little plane. The decision to fly again so soon does not strike him as remarkable. The statistics remained the same. He was in no more danger than he was when his son was alive.

Flying a plane can be exhilarating. It can be terrifying. To do it successfully requires the belief that you control the outcome. In that way, it’s like pitching. And for Roy Jr., it was like parenting.

Roy Jr. taught Roy III to master two things. Many baseball fans know how the father searched for a house with a basement at least 60 feet, six inches long; charted the son’s velocity; honed his focus. They do not know that the father also passed on another, greater love: for flying.

Those moments in the air brought Roy III such pleasure, but knowing how it all ended, his mother, Linda, wishes he had never had them. She is angry with her son for whatever happened that day, for whatever he did that took him away from her. His sisters, Merinda and Heather, agree. “I’d rather he be here and miserable,” Heather says. Roy Jr. does not traffic in counterfactuals.

“I wish that he had been more careful,” he says, “But I’m not sorry for what he was doing, and never sorry that he was enjoying his life.”

Father and son were so close that even the rest of the family believes Roy III’s death was hardest on Roy Jr. But he is determined not to show it. “There are a lot of people depending on me,” he says. “So you have to be strong even though you might not feel that way.”

Roy Jr. has mostly maintained his veneer of stoicism. Only the people closest to him notice how his words have softened since Roy III’s death. How he now calls his daughters to tell them, unprompted, how proud he is of them. How much gentler he is with his grandkids.

Roy Jr. does not take to the air to think about his son. He can do that on the ground. He can wonder what his son’s death says about his life, and what his life tells us about his death. He can wonder why he couldn’t save his son. He can wonder if he should have seen the end coming.

Two things: to pitch, and to fly. One gave his son life. The other killed him.

Back in the Chipmunk, Roy Jr. points out the Rocky Mountains to the west. These are his favorite moments, when the chaotic world shrinks beneath him.

Roy Halladay III is in the cockpit, logging his first official hours as his father’s aviation student. He is two years old. Roy Jr. does not think he is too young. It doesn't take too much, Roy Jr. thinks, molding Roy III’s hands around the control stick. He can keep the wings level.

Roy Halladay III did not file a final flight plan with the FAA. He did not make a mayday call. He was simply there and then he was not.

The last flight of his life, on November 7, 2017, lasted 17 minutes. He crashed in the Gulf of Mexico about 20 miles northwest of his home in Odessa, Fla., a suburb of Tampa. Telemetry data suggests that he was performing maneuvers you might see at an airshow: rocketing up, then shooting back down. He flew as close as 75 feet to nearby houses. Halladay was not certified in what is known as aerobatics, and he violated FAA regulations requiring a minimum distance of 500 feet from “any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure.” The toxicology report shocked the public. It did not shock his family. It revealed high levels of zolpidem—a sedative sometimes known as Ambien—amphetamines and morphine in his system. There were also traces of tobacco; hydromorphone, a narcotic often marketed as Dilaudid; and fluoxetine, an antidepressant sometimes sold under the name Prozac. The medical examiner could not determine the source of these substances or when he took them, but the FAA prohibits pilots from flying under the influence of most of them. If he had survived, he could have been prosecuted.

The Icon A5 is a $389,000, 23-foot-long two-seater powered by an engine descended from a snowmobile. Its wings fold in, its windows are removable and it can take off from and land in water. Its marketing materials describe it as being “like a fighter jet.” A witness told the National Transportation Safety Board he saw Halladay’s plane soar to between 300 and 500 feet, then make a sharp left turn and descend at a 45-degree angle. Then he saw the splash.

Tributes to the icon began almost immediately. Twenty-five MLB teams tweeted their condolences, as did teams in Philadelphia (Eagles, 76ers and Flyers) and Toronto (Raptors and Maple Leafs), the cities where Halladay spent his 16-year major league career. The Raptors held a moment of silence. Seemingly every baseball luminary past and present remembered him, many with stories.

Like this one: Phillies second baseman Chase Utley arrived at 5:45 a.m. on the first day of spring training 2010 to find Halladay drenched. “Was it raining when you got in?” Utley asked. “No,” Halladay said. “I just finished my workout.”

And this one: Two years later, Halladay and Tigers righty Max Scherzer faced off in spring training. Afterwards, Scherzer ate lunch, showered and was on his way to his car when he noticed Halladay on the back fields, soaked in sweat, running foul pole to foul pole.

Dodgers righty Brandon McCarthy tweeted, “Roy Halladay was your favorite player’s favorite player.”

Pennsylvania governor Tom Wolf and Toronto mayor John Tory expressed their sadness. Drummer Questlove, CNN’s Jake Tapper, pro wrestler Tommy Dreamer, gossip columnist Perez Hilton, actress Alyssa Milano—even the Philadelphia zoo weighed in.

Halladay’s little sister Heather could barely watch. She was the one who got the call from his wife, Brandy, all but incomprehensible through the sobs. Heather raced to reach her parents and sister before they saw the news. Her father did not believe it.

“Maybe they made a mistake,” he said.

Heather watched TV and wondered: How could people have filmed this? Why didn’t they help? He was still breathing when he hit the water—what if an extra few seconds would have mattered?

A week later, the Phillies hosted a memorial service at their spring training facility in Clearwater, 15 miles southwest of Odessa. A highlight video played and a string of baseball men spoke. Roy Jr. gave a eulogy. Brandy gave a eulogy.

Heather did not find comfort there. She had never cared about Roy the baseball star. She just wanted to find a quiet place to remember the Roy who, as a child, would run into a door to make her laugh when she was upset. It took her nearly two months to laugh again: She came upon a picture neither of his death nor of his life as a celebrity, but of her 40-year-old brother months before his death, having just caught a trout, pretending to poop it out.

His parents and sisters were not fully integrated into Halladay’s life as a major leaguer, and that distance did not close once he retired. They lived a continent apart, and life got in the way—his parents’ divorce, his sister’s baby, work, adulthood. That meant that the people who understood where he came from could not really understand what he was going through. And the people who understood what he was going through did not really understand where he came from.

At Bright House Field, before the service, one of Halladay’s post-baseball best friends, Bill Davis, noticed a group of All-Stars—Chris Carpenter, Cole Hamels, Frank Thomas—clustered together. These were the colleagues who loved Halladay most. Davis approached the group and gestured to a man standing alone. “I just want to let you know,” he told them, “That’s Mr. Halladay.”

Roy Halladay III is in the cockpit, his father by his side. He is 17, about to graduate from high school. He has nearly 200 hours in his logbook, but Roy Jr. refuses to allow him to fly alone. The father sees danger where the son doesn’t. Four years ago, the 20-year-old son of a local air-traffic manager went up with a friend on a perfect day, skimmed low over a reservoir and caught the edge of the plane in the water. Both young men died on impact. So Roy III has to wait.

Harry Leroy Halladay Jr. wanted to name his son Merlin—not for the magician, but for the Rolls-Royce Merlin, a World War II–era aircraft engine. But Linda nixed the name. The baby would be Harry Leroy Halladay III, and the golden retriever would be Merlin.

The Roys both hated Harry and they both hated Leroy. So they went by Big Roy and Little Roy. While baseball fans cheered Doc, he still signed his Mother’s Day cards Little Roy. Even now, that’s what his family calls him.

Big Roy believed his son could be a star pitcher. Little Roy loved baseball and ached to please his dad, so he did, too. Big Roy recited motivational phrases: “The attitude of success is a quality of mind that will give vigor and strength to all you do.” Little Roy recited them right back: “Stick to the task ’til it sticks to you. Beginners are many but finishers are few.” When Big Roy encouraged him to work on his grades, Little Roy began arriving at school at 6 a.m.

Big Roy taught Little Roy to finish a workout and ask, “Do we get to go again?” Big Roy would sometimes leave tiny traps to confirm that Little Roy was doing full workouts: a chalk line under the weights that moving them would erase, a loose pin in a bench that he would have to tighten before leaning back.

Big Roy remembers a child who defused parental anger with humor. Heather recalls a boy who sent himself to his room and waited anxiously for his dad to come home so he could apologize. When Little Roy was a young teenager, he put a fishhook through his pitching hand. He felt the fear of disappointing his father more acutely than the pain. Big Roy did not always see how much his approval meant.

When the Roys were not tinkering with Little Roy’s delivery, they fiddled with metal. They built and flew hundreds of model airplanes. They took apart Big Roy’s brother’s discarded old MG and restored it so nicely that he asked for it back. They refurbished an old Corvette. And they spent hours in the hangar, sprawled on the floor, repairing planes.

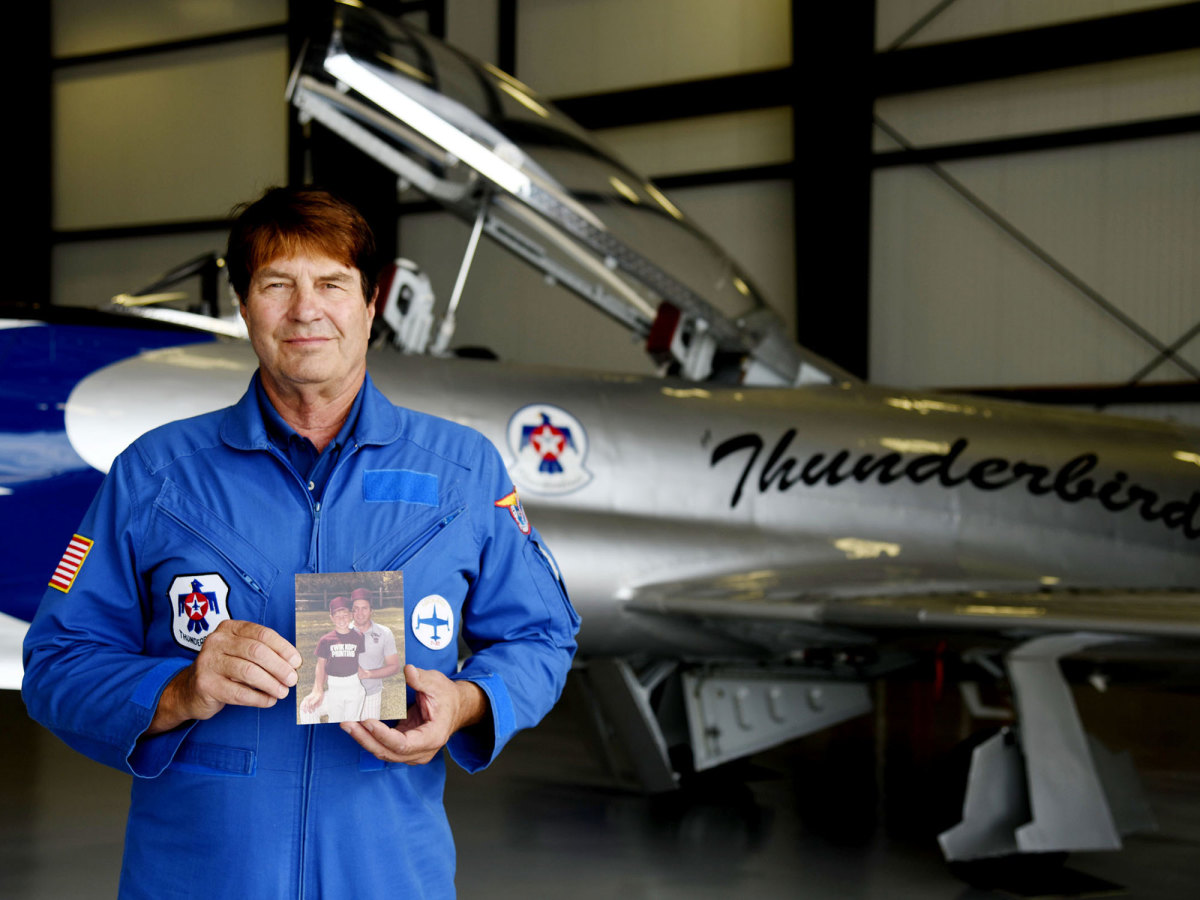

Their favorite was a Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star, a jet that made its military debut in 1948. Big Roy traded some car parts for this one—“just a piece of aluminum,” he says—in ’90. He bought pieces from junkyards and they got to work, stripping the plane down and rebuilding it. It took them a decade. The tail number is 514RH—Little Roy’s birthday and initials. The plan was for Big Roy to fly it down to Little Roy eventually and leave it for him as a gift. Instead, Big Roy will now sell it.

Merinda never really wanted to fly. Heather did, in part because she saw it as a way to spend time with her father. But she has only logged 17 hours in her 37 years. In Big Roy’s eyes, she says, “I just never compared to my brother. I didn’t want to be behind him.”

The girls teasingly referred to their brother as Prince Roy because their father was so devoted to him, but the devotion had a price. On birthdays, everyone else got a slice and Little Roy got the rest of the cake, but on drives home after games, the family listened as Big Roy lectured Little Roy on what he would do better the next time out. The girls did not envy their brother’s life.

“I feel like my brother lost out on a lot of his childhood,” Heather says. “I don’t fault [my dad] for it anymore, but I think that my brother could’ve been just as good without being pushed so much and having all that responsibility.”

In the years before he died, Heather and Little Roy looked back at their youth. Little Roy became everything he and Big Roy ever wanted: a two-time Cy Young Award winner, a capable pilot. But he admitted that he didn’t always get to be a kid.

Was it worth it?

Little Roy considered alternate realities: Alongside his dozens of baseball offers, he got the letter that tickled him most—a partial scholarship to play basketball at a junior college. He could have done that. He could have gone to Arizona, where he had committed before signing with the Blue Jays. He could have simply been a good high school pitcher then gotten a real job. But he was happy with the path he took. Little Roy told Heather the process was worth it because of the rewards.

For Big Roy, the process was the reward.

“When we were working on the T-33, we thought, Boy, I can’t wait to get it finished because we’ll go flying and it’ll be so much fun,” Big Roy says. “When we got it all done, we thought, That was sure fun putting it together. Flying is O.K., but the fun part was putting it together, and that’s kind of how I felt about [Little Roy’s childhood].”

Roy Halladay III is in the cockpit. He is an adult, a famous baseball player, but he still needs his father in the plane with him. Little Roy’s major-league contract forbids him from being the pilot-in-command. Big Roy tries to match his days off with Little Roy’s start schedule, and whenever they line up, Big Roy flies to watch him. Sometimes he can stay only a few hours. But when he can scrape together a day or two, they go up and tool around together. It helps keep them close.

Little Roy never won a World Series. He toiled for a decade in his prime for a moribund Blue Jays team that never made the playoffs. When Toronto traded him to Philadelphia before the 2010 season, the deal was widely regarded as a kindness: Finally, the ultimate competitor would have a chance to compete for something.

In his first postseason start, he threw a no-hitter. He told Big Roy afterward that he couldn’t hear anything while he was on the mound that night. “I wish I could figure out how to get that feeling more often,” Little Roy said.

So much of his life was noise. Shortly after that game, he entered a restaurant to a standing ovation. He turned and left. Big Roy had prepared his son for nearly everything—except fame.

Even after he retired, he could not escape. Geoff Miller, the Phillies’ mental-skills coordinator, once described trying to wrangle his kids and his bags onto a 5:30 a.m. flight. “Yeah,” Halladay answered. “Imagine everyone in that airport knew who you were and they were waiting for you to lose it.”

Over the years he learned strategies to winnow his focus. After a promising start to his major league career, he collapsed in his third season: a 10.64 ERA, a demotion all the way to Class A. He joked about jumping out a window. But then Brandy gave him a book, The Mental ABCs of Pitching, by Harvey Dorfman. (Brandy, through Davis, declined to be interviewed for this story.) It reminded Little Roy of how he had been taught to think as a boy. He devoured it and took notes in a journal. Eventually he befriended the author and handed out the book to his teammates.

When Halladay succumbed in 2013 to two stress fractures in his back and an eroded disc, he became a stay-at-home dad. But by April ’15 he was emailing the psychology department at the University of South Florida, asking if he could audit classes. He wrote, “I am comfortable in sports psychology with the 10 years I spent under Harvey Dorfman. I would however like to take some general psychology courses because I feel the root of many athletes struggles is a warped or underdeveloped self worth and identity.”

In 2017, he asked Phillies GM Matt Klentak if the team could use him. But he didn’t want to do what most former players enjoy, standing around in baseball pants and occasionally adjusting a pitcher’s grip. It wasn’t Halladay’s arm that had brought him back from the hole he once thought he’d be buried in. It was his brain. Klentak sent him to Miller.

Halladay made appearances during big league camp, but extended spring training was perfect for him. He worked mostly with young players, and the days ran from 7 a.m. until early afternoon. He spent a month developing how he would take notes. He bought a four-figure massage chair and offered sign-up slots to players. He held office hours. He patrolled the facility with a can of Dr. Pepper in his hand and two more in his pockets. When his coworkers cleaned out his office after he died, they found dents in the drywall from where he lost control of his drones.

He planned to fly himself to the minor league affiliates. (“I don’t know if the Phillies will reimburse you for the fuel,” Miller cautioned. “I don’t care about that!” Halladay said.) He gave journals to anyone who would take them. He discovered there was no audiobook of The Mental ABCs, so he booked studio space and paid someone to read it aloud. He planned to pursue a bachelor’s degree and eventually a master’s.

Outside of Bright House Field, Halladay coached his teenage sons, Braden and Ryan. He echoed his father’s insistence on persistence, but he did not push them quite so hard. Big Roy mentioned that Little Roy had been throwing 90 m.p.h. at 17, but Braden at the same age struggled to hit 80. Little Roy didn’t want to hear it. He was a father, too, and he would teach his boys his way.

He befriended Bill Davis, a captain in the Pasco County Sheriff’s office, and took him up in his Cessna 208 Caravan whenever they could sneak away. One time they flew to Orlando to play golf at Isleworth with Ken Griffey Jr.

Gradually, the A5 replaced the Caravan as Halladay’s preferred form of travel. He parked it in the lake behind his house and flew it nearly every day. He took his boys and their friends up. And sometimes he just used it to be alone. He seemed to be living a dream, but he was also trying to escape.

Flying or boating??? Who cares I love them both!! Icon A5 dream machine!! Jimmy Buffet you need one of these!!! pic.twitter.com/z6vBxxUCtB

— Roy Halladay (@RoyHalladay) May 18, 2016

Heather could tell he found the transition to retirement harder than any of them expected. He would eventually confide in her that he was struggling. He asked her: Do I have depression, or am I just lost?

“I think it’s probably a little of both,” she told him.

In April 2015, Little Roy was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame. Heather noticed a change in her brother: He seemed sweaty, dry-mouthed, lethargic. She asked Big Roy if he had noticed a problem. He told her the truth: Little Roy was addicted to lorazepam, an anti-anxiety drug often marketed under the brand name Ativan. He had been prescribed it, but eventually began abusing it. He had been to rehab, but he had relapsed. It was a “really dark period,” Big Roy says now.

Heather did not say anything to Little Roy. She knew how desperately he wanted to impress everyone in his life. But the August before he died, she and her family went to Disney World with him. Little Roy held the bags and waited as everyone else had fun; his back hurt too much for him to sit on any of the rides. Heather noted how careful he was not to mix up his painkillers. At one point he even declined an aspirin for a headache. Finally he confided in her: Addiction was “a wicked thing,” he said. He encouraged her never to accept a prescription for lorazepam. He had been back to rehab. They had given him a journal there. It seemed to be helping.

“You made a smart choice,” she told him.

Now she sighs and says, “I think he felt like he needed to hide his mistakes because he didn’t want anyone to think he wasn’t as good as they thought he was. He thought they wouldn’t understand that he was human. Just because you’re a good baseball player doesn’t mean you don’t make mistakes.”

He seemed surprised at how well the family had handled his revelation. Big Roy had always been strict about drug and alcohol use, but even he reacted gently. Heather thought Little Roy was beginning to realize he did not have to carry his burdens alone.

He had spent so much of his life trying to be who everyone else wanted him to be. He was not sure who he was outside of baseball—who he was as a husband, a father, a friend. But buzzing around among the clouds, he answered only to himself. His mother and sister believe that was the appeal of flight.

“I think he finally felt free,” Heather says softly.

Had he ever felt freedom before? Heather and Linda look at each other.

“No,” they say, together.

Roy Halladay III is in the cockpit with his father, getting the hang of his new Caravan. Little Roy is retired now, but even as the rest of his life shifts, his love for aviation remains constant. When Little Roy shops for planes, he brings Big Roy along for the test flights. Long after Little Roy has stopped needing Big Roy’s input on grips or deliveries, father can still teach son about flying.

Big Roy used to love picking up Little Roy from school. He wanted to know every single thing happening in his son’s life. They talked on the phone two or three times a week once Little Roy was drafted, in the first round in 1995 by Toronto, and the connection remained strong. But, Big Roy says, “that density of time disappeared.” At times they could go a month without a phone call. This happens to parents of adult children: First there is physical distance, and then eventually there is emotional distance.

The Roys papered over that gap by tracking each other’s flights online. It was a way to stay close even when they could not find the time to be together.

Big Roy rarely tracked the A5—its flights were too short—but the plane worried him. Big Roy did not approve. He considers light-sport aircraft to be a dalliance, and not a particularly safe one. There had been two accidents in the A5, one fatal, he reminded Little Roy. In more than a dozen conversations, he made his case: The plane itself was well made, but it encouraged bad behavior.

Now this is FLYING!! Love this airplane!! The Icon A5!! If you fly or ever dreamed of flying this is your airplane!! pic.twitter.com/KVq8aSkpRE

— Roy Halladay (@RoyHalladay) May 18, 2016

Little Roy had said he felt like he was flying a fighter jet. “You’re not,” Big Roy reminded him. “Be careful.” When he died, Little Roy had 703.9 hours. Insurance rates generally decline at 1,000. Big Roy had told him that he was in the danger zone: enough experience to feel confident, not quite enough to have mastered aviation.

At first, Big Roy’s virtual co-piloting just left him proud of his son’s judgment. But starting a year or two before Little Roy died, Big Roy began to grow concerned. Little Roy seemed to be taking unnecessary risks. There was one trip in the Caravan, from Dallas to Miami, clear across the Gulf of Mexico, that especially upset Big Roy. “That’s too aggressive,” he said. “You need to dial it back.”

Little Roy seemed to hear him. But Big Roy kept tracking, and he kept worrying.

Roy Halladay III is in the cockpit, alone. He loves it up here. It’s a week before the crash. Big Roy is on the ground, and he is concerned. He calls Little Roy and begs him to be careful. Your favorite player’s favorite player is still his father’s little boy. It is the last conversation they will ever have.

What, exactly, happened on the last day of Little Roy’s life?

Was this just an accident? Big Roy has examined every report. He has watched every video. He spent three hours on the phone with Noreen Price, the lead NTSB investigator assigned to the case.

Initially Big Roy had believed that the one of the wings got caught in the water: a misjudgment by a man suffering from what Big Roy refers to as “hot-rod-itis.” But Price said that all their telemetry data suggested that the Icon was flying at 36 feet before the nose suddenly pitched up, then dove down. Big Roy asked if the center of gravity was off somehow. He asked if there was too much pressure on the plane, and the wings stalled, and it dipped. He asked what the G-load was.

Price said that she didn’t know, she didn’t know and she didn’t know. She can’t know, she says now. “You never can,” she says, “Unless there’s a camera in the cockpit recording everything.” Big Roy called an engineer friend and asked him whether the plane could have gone into a deep stall. He didn’t know.

Was Little Roy too high to understand what he was doing? His family derives some comfort from the knowledge that the medical examiner did not find lorazepam in Little Roy’s system. But the narcotics … the Ambien … the Prozac ... the concentration of amphetamines alone could have killed him. He might have been too impaired to walk safely down the street. They think about that toxicology screen and they wonder if his darkness smothered him.

Did he take his own life? He was planning for the future: a second home in Denver, more time together. But depression is a powerful disease.

“I don’t know,” Big Roy says.

Finally, he stopped asking. But not because he believed the answers do not exist. If he just read one more report, studied one more video, asked one more question—if he just kept digging, he is sure, he could understand what happened to his son. He considered hiring a private investigator. Then he decided against it.

“I’ve kind of come to the conclusion that I don’t need to know exactly why,” he says. “I just know that it did happen. And I’m not going to investigate it anymore, because the more you get into it, the more grief you can cause yourself. Now I don’t have to concentrate on those things. I can think about what a cool kid he was.”

This is what he knows: At 11:47 a.m. on November 7, 2017, Little Roy took off from the lake in his backyard. He kept the wings level. The chaotic world shrank beneath him. Up there, it was quiet, and he was free.