The Death of Paper Tickets and the Stories They Leave Behind

This story appears in the Sept. 23, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated.For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

John Burns held season tickets to Xavier basketball games for more than 40 years, in three different Cincinnati arenas, his seats maturing along with him—from raucous baseline in youth, to second level near the beer stand in middle age, to wheelchair-accessible seats when his aging friends required them. They were like The Giving Tree, those tickets, which Burns shared with seven pals. "Eventually, Dad needed the disabled seats himself," says his daughter, Mary Ann. "I can still see him sitting at the dining room table, dividing the tickets into envelopes. Dad was always The Guy in Charge of the Tickets."

John Burns died at 78 on April 1, 2010, his spirit ascending skyward in the manner of his seat location. In his casket his family placed objects he esteemed: a thoroughbred racing form, a pencil to pick the winners and a can of Cincy's own Hudepohl beer. "But the thing he loved most in life was Xavier basketball," says Mary Ann. And so Burns wore his season tickets into eternity, tucked into his funeral blazer like a pocket square. They were fanned out for St. Peter, expediting him through heaven's gate, a reminder that the cheap seats high up in English theaters and soccer stadiums are called "the gods."

Like the golden ticket in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or the letters of transit in Casablanca, tickets almost always provide passage to a better place. They are redeemable, like our souls; and like our souls they may be sold on the secondary market. As with the afterlife, tickets promise a better future. They don't always deliver on that promise, but tickets—be they baseball or raffle or lottery—provide hope before the reckoning.

"I grew up outside L.A., was a huge Dodgers fan as a kid, and to get tickets you had to go to a little department store called Holbrook's that sold gym clothes and Boy Scout stuff and had a ticket service to Dodger Stadium," says Russ Havens, who at 54 is old enough to remember a time—the mid '70s, in his case—when there were still department stores with their own box offices that sold tickets made of thin cardboard to Boy Scouts. "I'd buy tickets weeks in advance, pin them up in my bedroom, and those tickets would remind me every day: Hey, you're gonna see the Dodgers. I held onto those stubs." And those stubs held on to him.

"Say you're 10 and you go to a game with your dad; you give [the ticket] to the attendant, the attendant tears it and—boom—that stub is your memory," says Gary Piattoni, a collectibles appraiser who appears regularly on Antiques Roadshow. "These are the objects that make an imprint at an early age, before you discover the opposite sex."

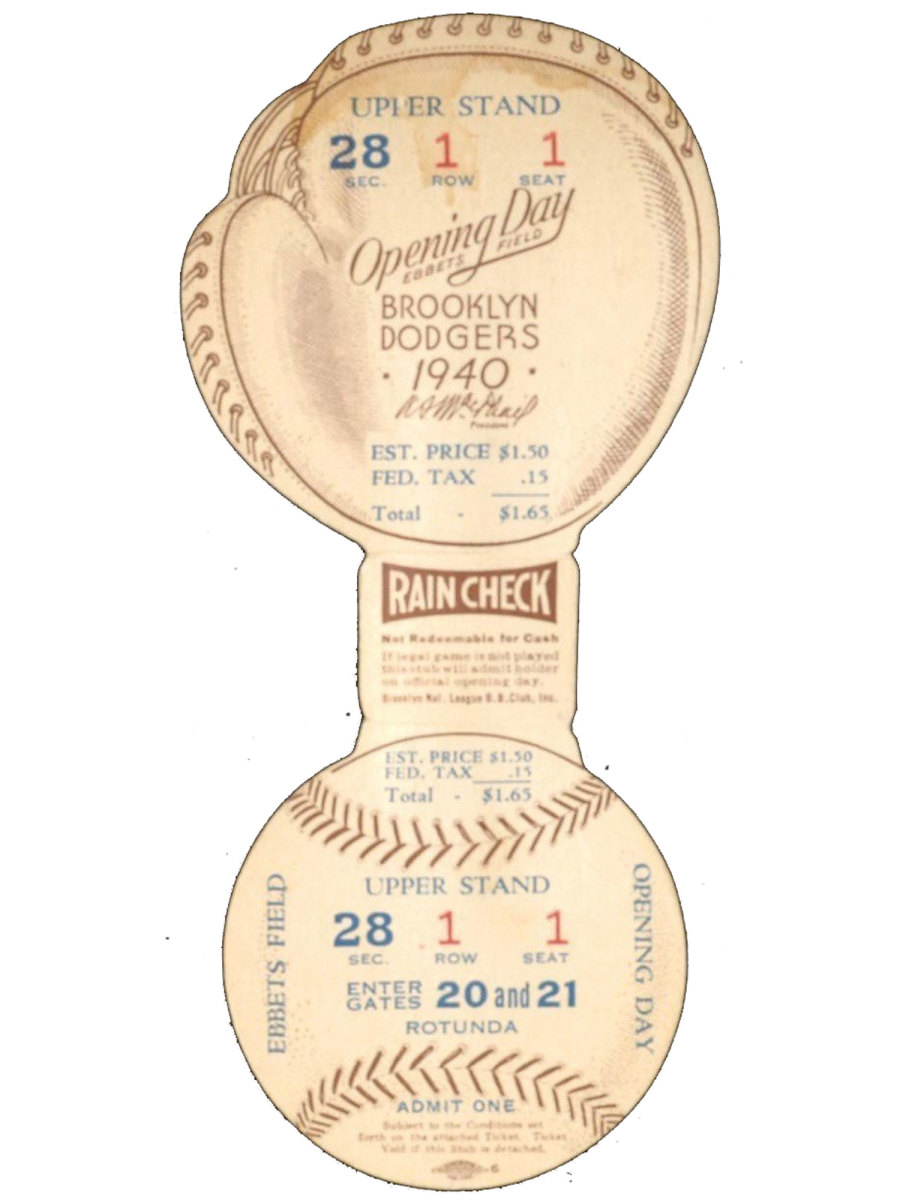

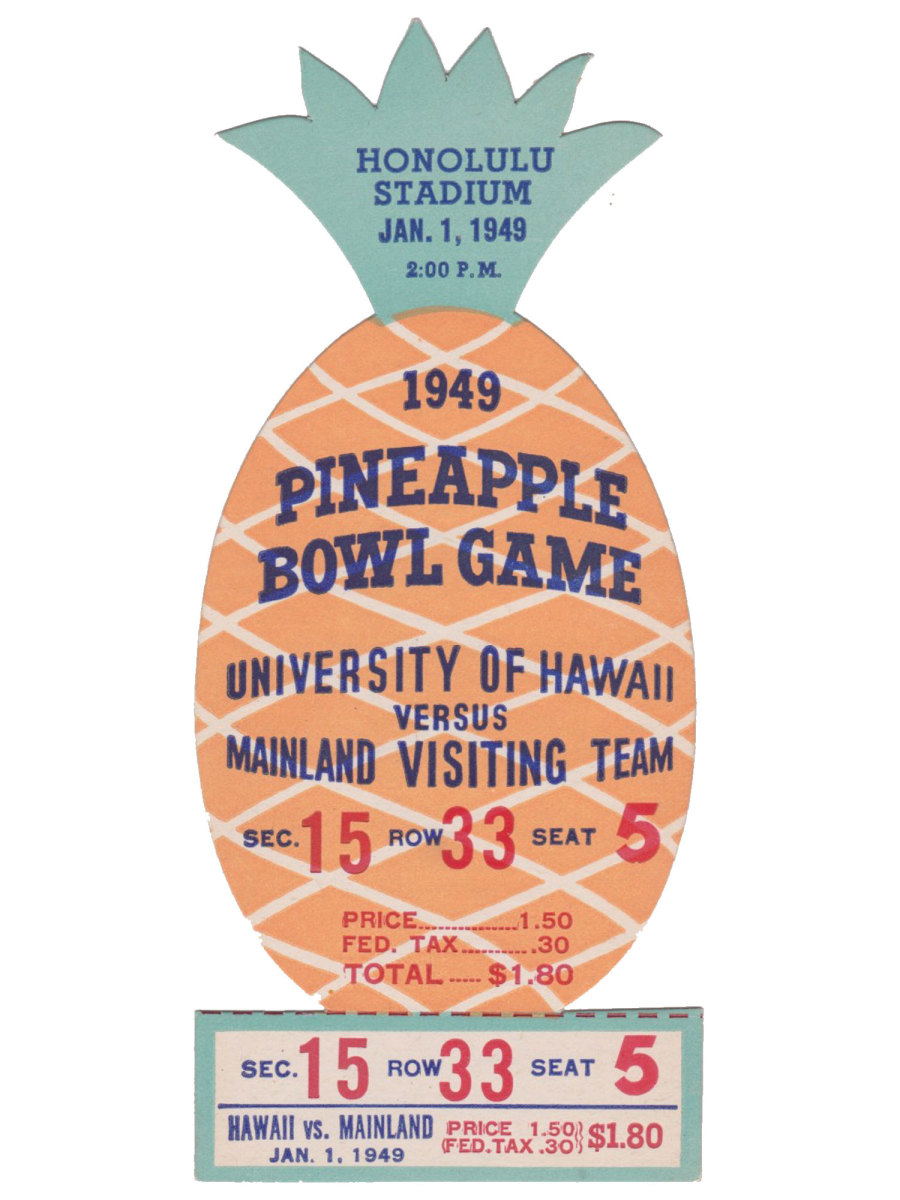

Tickets have often been objets d'art in their own right, something to hold and to behold. All 15,000 attendees at Honolulu Stadium on New Year's Day 1949 would have been reluctant to surrender their tickets to the Pineapple Bowl, so beautiful were those die-cut ducats shaped like the tropical plant. The Brooklyn Dodgers' passes for Opening Day of '40—a die-cut ball and glove, linked by a rain check—were more beautiful still. Anyone watching the two parts ripped asunder at an Ebbets Field turnstile would have experienced a special kind of separation anxiety. "That ticket is the holy grail," says Havens, curator of Ticketstubcollection.com, a site devoted to ticket artwork and history. His 12-year-old son and 16-year-old daughter, though, don't share his passion for old strips of cardboard. To them, he says, "it's an absolute mystery."

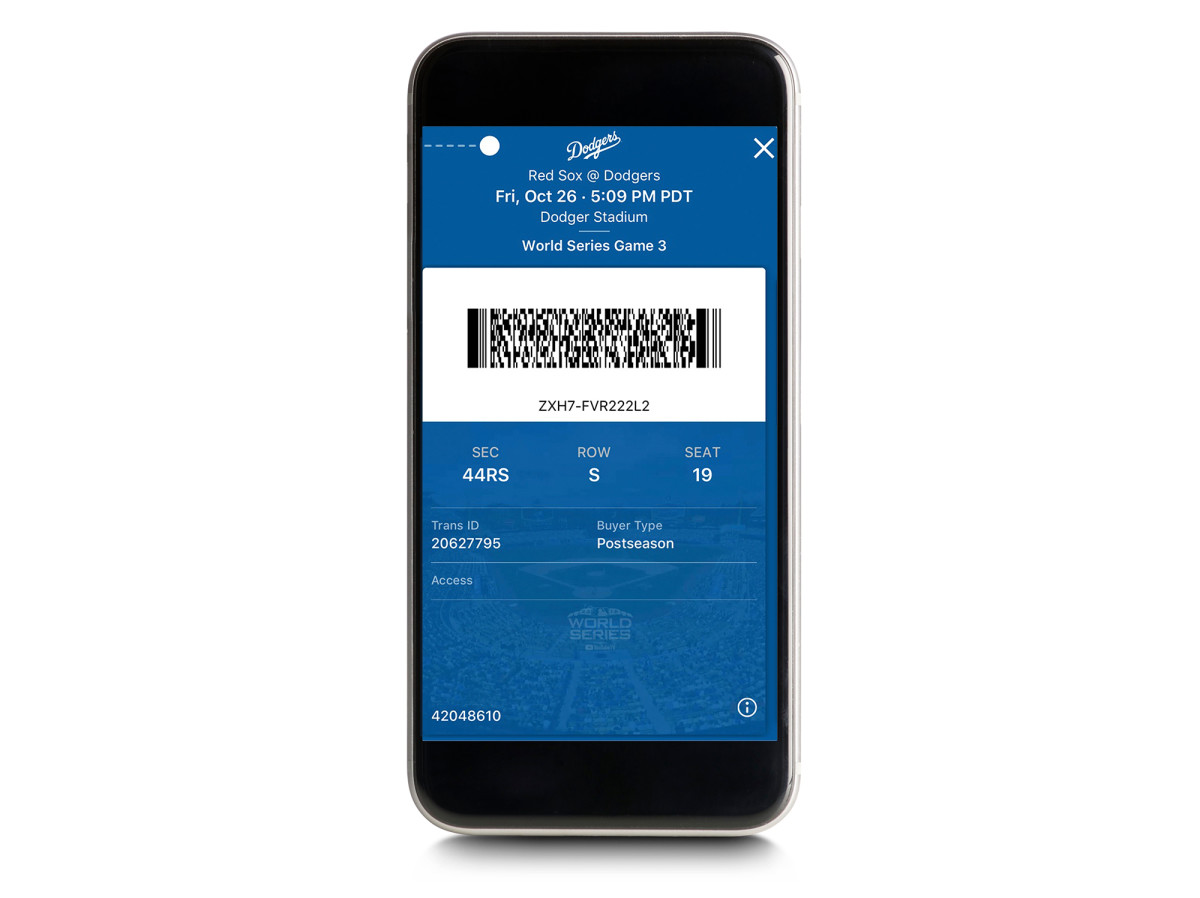

That's because tickets in the last decade have, like John Burns from Cincinnati, transitioned out of the physical realm. They are now, largely, purchased on and delivered to a mobile device, then scanned at the former site of the stadium turnstile. There is no more Guy in Charge of the Tickets, stuffing envelopes in his dining room, because fans now share tickets with one another on their phones rather than rendezvous at the giant bat outside old Yankee Stadium.

Today's tickets aren't keepsakes to take home, much less to the grave, for QR-coded receipts—bought on a secondary market like StubHub and printed at home—are nobody's idea of a souvenir. At heaven's gate, should you make it past the guy with the latex gloves and the hand wand, St. Peter will greet you now with a handheld scanner.

The NFL last season did away entirely with hard tickets, going "fully digital," a technological milestone—like Dylan going electric—that has its drawbacks and consolations. In the NBA, you can still walk up to, say, the Miami Heat box office and buy a ticket, but it will be sent to your iPhone, not slid through a window. And baseball: "You can go to the box office and get a commemorative ticket [at most stadiums], but far fewer people do that than you'd think," says Noah Garden, who oversees MLB's ticketing. The number of fans who still use hard tickets, he says, is "very, very low. Really low."

And why wouldn't it be? Mobile tickets are infinitely more convenient and secure. You can't lose them. But the question remains: As physical tickets disappear, have we sacrificed something precious, like art or memory or the joys of inconvenience?

Todd Radom knows "the polarized nature" of tickets in 2019. "I'm a Red Sox fan, and I was at Games 3, 4 and 5 of the World Series [last year] and saw the Red Sox win it," he says. "I had electronic tickets. Great! I could transfer a ticket to my friend. But I also wanted a memory to feel and touch and look at—and, really, there's nothing to look at with a screenshot."

Which isn't to say Radom didn't screenshot his mobile ticket. Of course he did. He is, after all, a graphic designer who has created throwback hard tickets for Tigers and White Sox premium season-ticket holders. "I print them out," he says of his screenshots. "It's still a record." With tickets, as with many other technological innovations, progress is complicated. Something is lost and something is found.

Found in the rubble left behind by the Joplin, Mo., tornado of 2011: a ticket stub for a March 14, 2002, spring training game between the Dodgers and the Cardinals. Some person saved that stub for nine years, the token of a Thursday afternoon in the sun at Holman Stadium in Dodgertown, a split-squad exhibition, Albert Pujols homering for the visitors, who won 4--1 beneath a canopy of blue—all those memories igniting when a finger comes in contact with the touch-paper of a ticket stub.

In such a circumstance, the hard ticket is irreplaceable. It always was. Wonka's golden ticket warned, "Be certain to have this ticket with you, otherwise you will not be admitted," and the anxiety that this knowledge induced was part of every excursion to ballpark or airport, panicky men and women frisking themselves, inquiring in the car, in a rising Jerry Seinfeld voice: "Do we have the tickets? Who has the tickets?!"

Digital tickets are easily replaced, thank goodness, but this safeguard against loss is itself a kind of loss. Time was, if you lost your ticket—often while inebriated in a bar—you placed a newspaper ad. "LOST—Twins baseball tickets for Sept. 21 [1965]. Vicinity of Mart Bar. 8th & Wash. Will finder please return...." Ads like this one, in the Minneapolis Star, frequently ran in newspaper classifieds, two more artifacts—newspapers and the classified ads within them—displaced by a digital simulacrum.

This paper-to-digital revolution has cut both ways for Russ Havens. After 1,300 used tickets and stubs were stolen in a burglary of his house, he was grateful that he'd already scanned them to his computer.

Is it perverse to long for a less convenient time, when printed products prevailed and fans sometimes had to be collage artists or crime-scene re-creators merely to attend a game? The wife of a Packers fan accidentally put his playoff ticket through a paper shredder in 2008. Reds fans occasionally saw their tickets destroyed in the rinse cycle, a team ticket manager said in the 1970s, back when the biggest nemesis for the biggest fans of the Big Red Machine was the Big Wet Machine. One U.S. Open golf spectator was given a replacement ticket after persuading officials that his dog really had eaten his pass. But the Michigan State basketball season-ticket holder who inadvertently threw his tickets into his fireplace while burning old files was SOL. His tickets did not rise, phoenix-like, from the ashes. Nor will paper tickets more generally.

In 1997, a Mets fan had no trouble getting into Shea Stadium with his baseball tickets—but once there he watched his theater tickets blow onto the screen behind home plate. The fan climbed the netting to retrieve them. These misadventures are no longer commonplace, so let's pass a reverential moment for the men and women who sacrificed in a previous age. Michael Smith and his wife, Pam, accidentally threw away their tickets to the '89 World Series and then spent hours searching through three tons of trash at a marina garbage disposal site in San Francisco, where they eventually emerged—malodorous but victorious—with tickets in hand. They would be forgiven for waving those tickets over their heads in triumph, like Wall Street traders waving buy orders on the floor of the stock exchange. The hard ticket, bought with hard cash, was hard-earned.

If you’re 10 now, you've never seen a ticket, so at 50 you won't say you wish you had them," says Gary Piattoni, who likens hard tickets to the tin toys popular at the turn of the 20th century: no longer desired as collectibles as their devotees die off. By 2100, no one alive will know why they're saying, when declining an invitation: I'll take a rain check.

Until then, there remain collectors of old ticket stubs, tokens of events attended by others. A mezzanine box ticket to Yankee Stadium on July 4, 1939—signed by Lou Gehrig on the day he retired and called himself "the luckiest man on the face of the earth"—sold at auction in 2014 for $95,600. (Original price: $2.20.) Of the 61,808 tickets to that game, two are reported to have survived. By comparison, stubs from Game 3 of the 1932 World Series at Wrigley Field—on the day Babe Ruth may or may not have called his shot—go for several thousand dollars on eBay. Such stubs are often "slabbed" beneath clear plastic and preserved like Lenin in his glass tomb.

Speaking of tombs, tickets will still be taken to the grave in decades distant, but not in the way John Burns took his. Last year Ilja Pankow, a 31-year-old supporter of Hertha Berlin in the German Bundesliga, won a fan contest with the prize of a lifetime ticket to see his favorite soccer team play, though the ticket came as a matrix barcode tattooed on his right forearm, scannable at the turnstile. An A's fan had his own $48 ticket to the May 9, 2010, home game against the Rays rendered onto one of his calves as a tattoo, replete with bar code, to forever commemorate Dallas Braden's no-hitter that day, as viewed from Section 119, Row 10, Seat 9. St. Peter will know where to put this guy.

Tickets also have the power to reanimate the departed. "I think about people I went to games with, many of them no longer with us," says Todd Radom, leafing through an album of stubs at his home in Brewster, N.Y. "I'm looking right here at April 30, 1977, Yankees and Mariners at Yankee Stadium, and remember it distinctly. That was the first month of the Seattle Mariners, I went with my uncle Gus, the Yankees became a World Series team, and I would go to the Series with my dad. I'm 55. I was 13 at the time. Uncle Gus departed this earth many, many years ago. I look at this now and think of him.

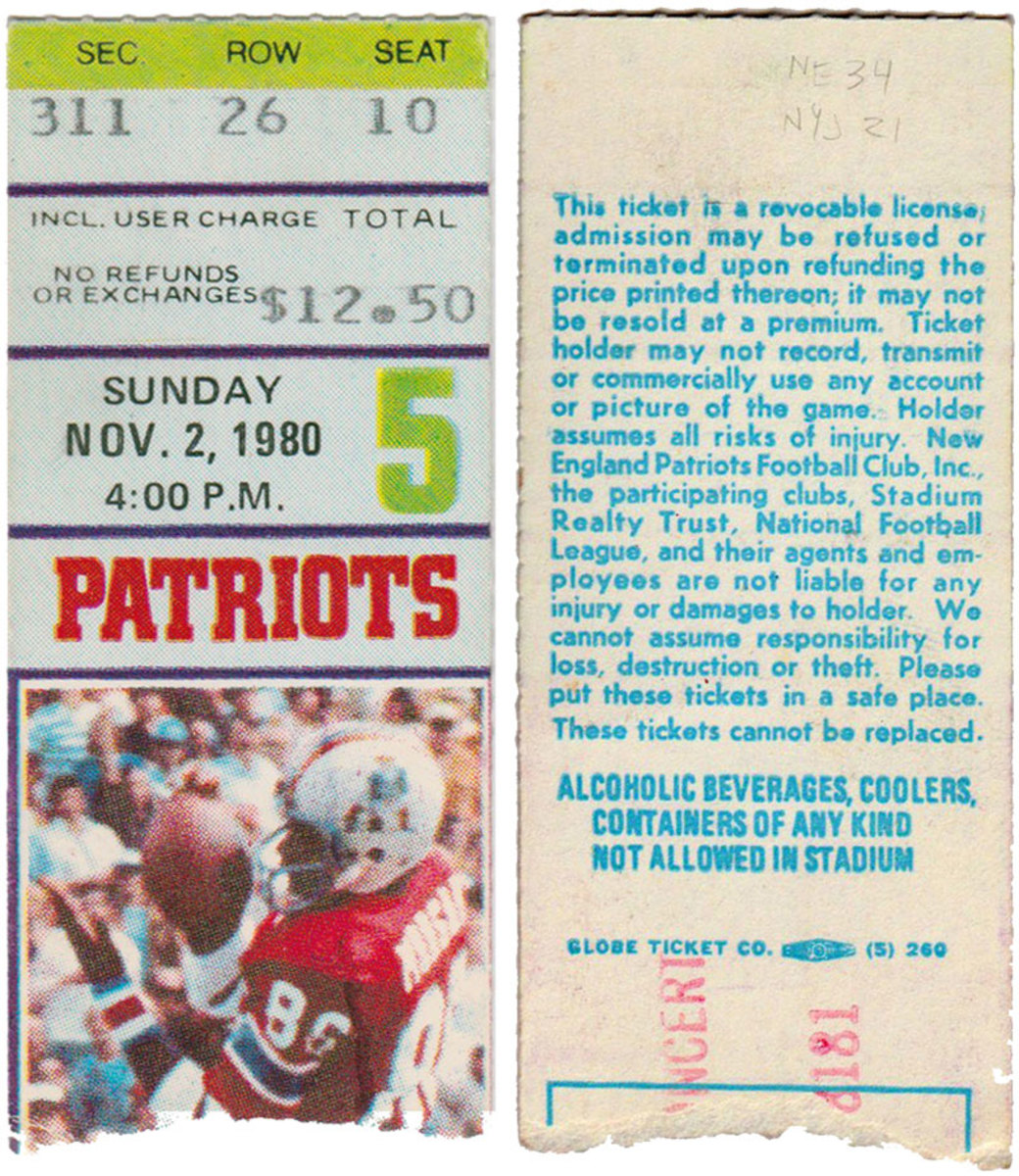

"This is from a game at Schaefer Stadium with my father," he goes on, rifling through his tickets. "A Pats game in 1980 against the Jets. Turn the thing over and I wrote the score in pencil because it's 1980 and they haven't invented the Internet yet, so how will we ever remember what the score was?" That score, as he wrote as a 17-year-old: Pats 34, Jets 21. "Sunday, Nov. 2," he says, lost in reverie. "The ticket has a picture of Stanley Morgan on it. We sat in Section 311, Row 26, Seat 10."

Radom's father, Carl, died in 1984.

One Saturday in the fall of 1970, a woman walked into Nau's department store in Green Bay and bought an $80 suede coat. She returned it two days later, on a Monday. Her husband didn't like the coat, she said, and so she hadn't worn it. A Nau's worker refunded the purchase price and only later found, in one of the pockets, a Packers ticket stub for Section 18, Row 23, at Lambeau Field. The coat—having enjoyed a single Sunday of freedom in the West Stand, near the 40-yard-line—was then placed in a rummage sale. New price: $17.

Tickets were once smoking guns, exonerating suspects in courtroom dramas—My client was at the theater, your honor—and incriminating suspects in real life. In August 1961, an 80-year-old woman was brutally attacked in Washington, D.C. At the scene, police found a ticket stub from the previous night's Washington Senators loss to the Angels, at Griffith Stadium. The Senators I.D.'ed the ticket buyer, detectives interviewed people seated near him, and the man was arrested and charged, the stub providing a primitive kind of DNA.

In 1974, police in Oakland sought a man they believed responsible for two similar robberies—both were committed in taverns, and in both cases the gunman insisted his victims drop their pants. Whether this was done to prevent the poor saps from pursuing him or for the gunman's own amusement, police didn't say. The thefts, combined, yielded $2,100 and three desirable tickets to an A's game against the White Sox, on a Saturday in late September, with Vida Blue on the mound for the two-time defending world champions and Reggie Jackson batting cleanup. Security guards at Oakland Coliseum, notified by the cops, waited at the seats and apprehended two teenagers, one of whom said he got the tickets from his 25-year-old brother—not exactly a criminal mastermind—for whom an arrest warrant was promptly issued.

The physical ticket was easily stolen and easily fenced. In April 1977, in the first month of the Mariners' existence, a Seattle attorney had her purse stolen, with two tickets to the M's game against the Twins inside. She and her husband attended anyway, on different tickets, and stopped to see who was sitting in their seats. To their surprise, it was a Seattle police sergeant, who said he'd been given the tickets by someone he'd pulled over for driving without a license, who in turn claimed to have bought the tickets from a guy on the street, who almost certainly had his own alibi, and so on, into infinity. The cop and his son switched seats with the attorney and her husband; the Mariners walked it off in the bottom of the 10th for a 3--2 win over the Twins; and everyone involved knew that former Dodger general manager Fred Claire was right when he said of tickets: "With each stub comes a story."

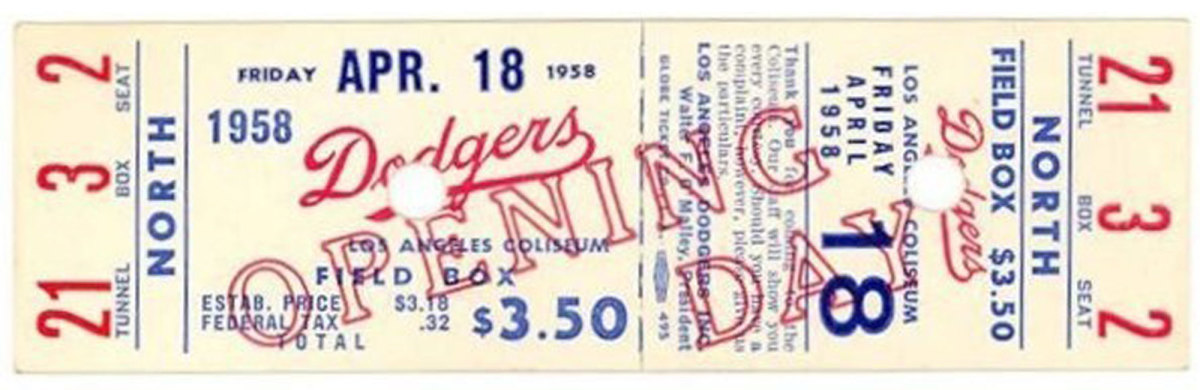

In 1970 the Dodgers offered free tickets for their 1,000th game in L.A. to any fan who could produce a stub from the team's first game there, in '58. "Who keeps tickets?" asked Claire, who then worked in the team's p.r. office. As it turned out, more than 500 people had.

Mrs. Richard Miranda of 739 North La Jolla Avenue had kept her stub because, as she wrote to the Dodgers: "This was my first time at a baseball game and Opening Day was a big thrill to my husband and two-year-old son. My boy was allowed to slip under the rail without a ticket. As you probably have guessed my son now is 15 and can no longer slip under the turnstile." The stub was a permanent reminder of an age when her nearly grown boy was small enough to hold on her lap.

"Every ticket tells a story" is a concept around which Matt Peter built an entire website, Stubstory.com, where fans can submit their sports or concert stubs and share an anecdote about them. ("Same church, different pew" as Havens's site, says Peter. Leave it to a ticket-stub collector to use a metaphor that requires an usher.) In one of those tales, 11-year-old Dan Erhardt had tickets to see David Cone pitch at Yankee Stadium on Yogi Berra Day—July 18, 1999—with Don Larsen throwing out the ceremonial first pitch. But Erhardt's dad decided, in the mysterious way of dads, that they couldn't attend that Sunday. Naturally, Cone threw a perfect game, as Larsen had done 43 years earlier in the World Series, and Erhardt's father framed the intact tickets, hanging them on the wall of their rec room as a lasting reminder—and also a lasting rebuke. Wrote Erhardt: "I can't watch any highlights of that game without looking to the sky and wailing, 'Why, God? Why?!'"

The unused ticket has that effect. There is value in never having been used, but like a Han Solo action figure forever imprisoned in his box, it's also a symbol of all the fun you didn't have, and never will. Russ Havens has a buddy whose car broke down en route to the Fabulous Forum the night the Kings' Wayne Gretzky scored goal number 802, breaking Gordie Howe's NHL record. "The ticket is now worth more than the car was," says Havens.

On the other hand, imagine you had four tickets to see the 13-0 Patriots host the Jets at Gillette Stadium on Dec. 16, 2007—but the night before that game, your two-year-old daughter was in the arms of her grandmother when they both fell down the stairs to the basement. Your daughter broke her leg, her grandmother shattered both wrists. The two of them were in the hospital overnight, as a Nor'easter came through New England, closing roads, and those tickets, for that unattended game, sat in your desk drawer for the next 12 years. Now imagine you were assigned to write about tickets for SPORTS ILLUSTRATED, and you could reach into that desk drawer and feel those tickets, and instantly conjure four empty, snow-covered seats—Section 108, Row 35, Seats 19--22—and the mother-in-law who has since passed away, and that two-year-old daughter, who had lay beneath her grandmother in a heap at the bottom of the stairs. She is now a 6'2'' teenager.

Is that writer shedding a tear for the passing of tickets, or for the passing of time? Is that writer—O.K., is this writer—just missing his uncle John, who lived in Cincinnati and loved the horses and Hudepohl beer, and really loved the Xavier Musketeers?

Every ticket is a license. It says so in the boilerplate on the back. It demands good behavior and requires the bearer to observe a litany of rules: no smoking, NO BAGS, NO RE-ENTRY.... It's easy to forget that the English etiquette derives from the French word for ticket, estiquette, because most boors at games justify their profane screaming with, I bought a ticket, I can say what I want! In that way, the ticket was a different kind of license, authorizing the holder to call the ump a bum. Like a driver's license, you didn't leave home without it, which is why for most of sports history fans reflexively frisked themselves before heading to the game.

"I still do that," says Matt Peter. "I still feel my pockets for tickets before leaving the house." It's the phantom pain of a phantom limb, an ancient muscle memory rendered unnecessary by technology.

The modern marvels that have made life easier can also make it slightly disorienting, and infinitesimally less interesting. Young people don't care that tickets have largely gone away, nor should they. Even old Luddites have welcomed the conveniences wrought by Silicon Valley. But the knowledge that they'll never again forget their tickets has also left some fans—usually of a certain age and disposition—feeling the way those tickets once were, and will never be again. Torn.