The Curse of Bunned Meat and Breadsticks: Why the Twins Can't Beat the Yankees

This story appears in the Sept. 23, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated.For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

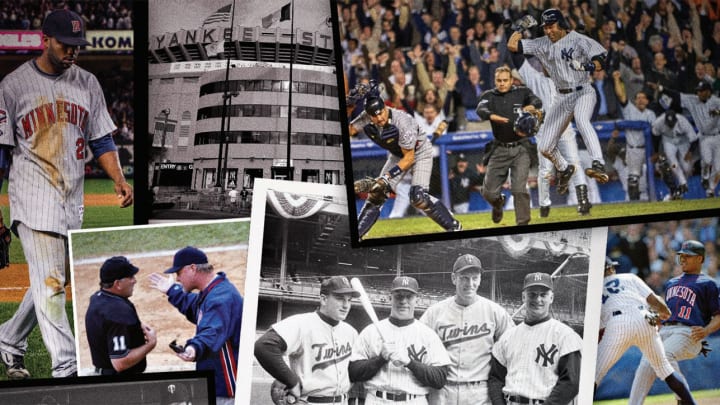

On April 11, 1961, the Twins played their first game, beating the American League champion Yankees 6-0 in front of Marilyn Monroe, Joe DiMaggio and Toots Shor, who sat beneath that white scalloped frieze at Yankee Stadium, its famous arches suggesting grandeur, antiquity and empire. The new home of the Twins, meanwhile, was a minor league ballyard in a former Bloomington, Minn., cornfield, providing the first of many comparisons between the two teams and the communities they represent in which Minnesota always comes off as a lesser New York—Big Apple vs. Minneapple, Yankees vs. Twinkies, Mickey Mantle vs. Mickey Hatcher.

Even the franchise's inaugural victory was largely forgotten by the next morning, when Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space. But the ballgame remains historic, for it began the Twins' own long-standing Cold War with the Yanks. As those two teams await the 2019 playoffs and another possible matchup, Minnesotans are keenly aware (as New Yorkers are not) that the Twins have lost a record 13 consecutive postseason games, an ignominious distinction they share with the Yankees' more famous rivals, the Red Sox. Minnesota's last playoff win was at the old Yankee Stadium on Oct. 5, 2004, in Game 1 of the AL Division Series. Of the 13 losses that have followed, all but three—a sweep by the A's in the '06 ALDS—were to the Yankees, most recently in the '17 wild-card game. For almost the entire 21st century the Bronx Bombers have had Minnesota's number, and that number is still stored in a Nokia flip phone.

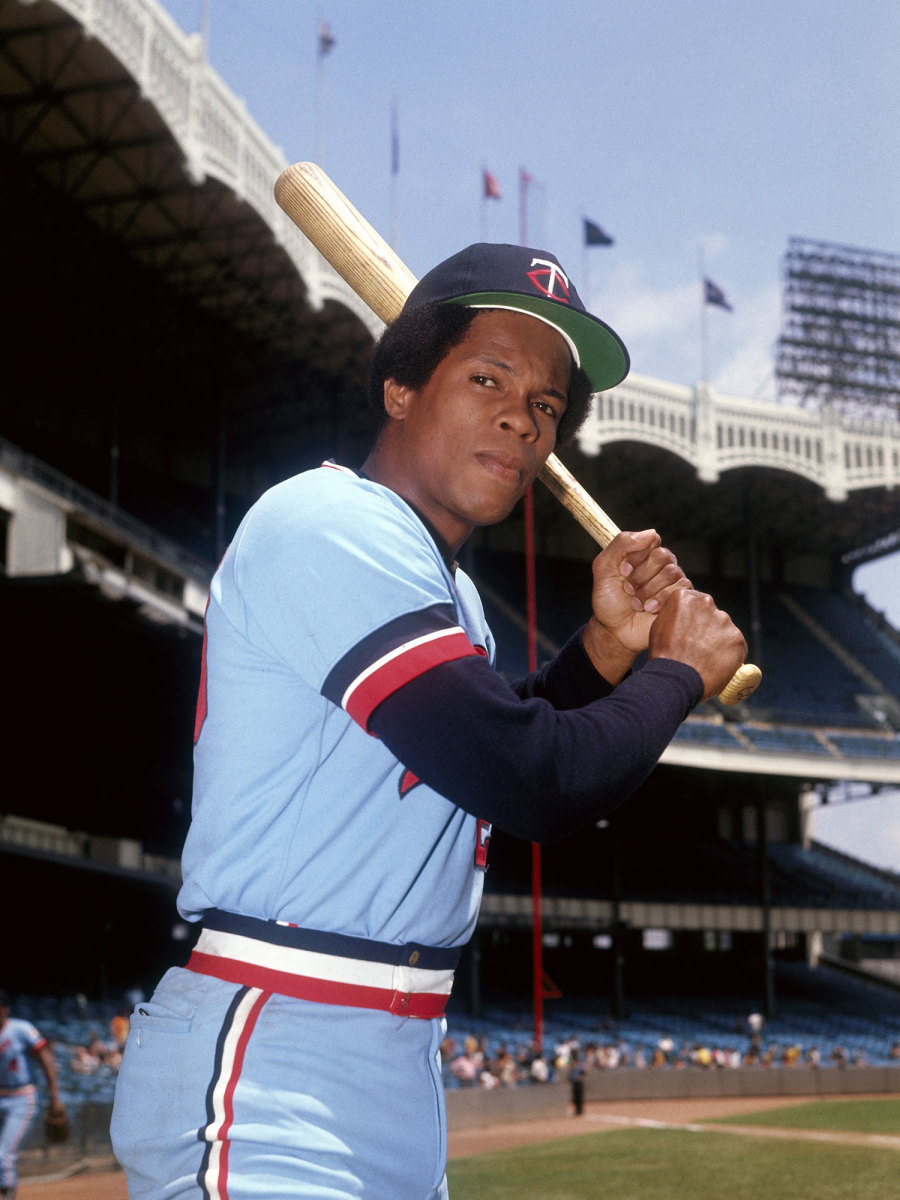

The Yankees' inexplicable domination in this century began very differently in the last one. In 1964, a recent graduate of George Washington High in Washington Heights—a Panamanian national then playing for a sandlot team in the Bronx called the N.Y. Cavaliers—traveled a couple of miles across the Harlem River to work out for the Twins at Yankee Stadium. After just a few swings Minnesota officials bundled the 19-year-old out of sight, lest he be seen by a Yankees executive with a fat book of blank checks. They spirited Rodney Cline Carew to an Italian restaurant in the Bronx, the Stella D'Oro, across from the breadstick factory of the same name, and signed the second baseman on the spot. It was a bank heist in broad daylight, and one for which there would be disproportionate karmic payback.

Carew would be named the AL Rookie of the Year in 1967, then win seven batting titles (while the scouts who signed him—Herb Stein and Monroe Katz—were given, for all we know, Bronze Breadsticks). But in '78, with the frugal Twins intent on dealing him, Carew expressed his desire to play for the Yankees, in the stadium where it all began. "I'd rather hit there than in any of the other teams' parks," said Carew, who also admired New York's skipper, Billy Martin, his former manager in Minnesota and the godfather to the second of his three daughters. Alas, Carew also had the temerity to entertain other offers, upsetting Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, who thought the future Hall of Famer didn't sufficiently appreciate "the privilege of playing for the Yankees." So Carew signed with the Angels and the Yankees maintained their imperious and often disdainful view of the Twins as backwater tightwads who didn't sufficiently appreciate the privilege of playing against the Yankees, much less for them.

You could hardly blame them. In 1979, Steinbrenner fired Martin after he punched out—of all the provincial Midwestern occupations—a traveling marshmallow salesman in the bar of a Bloomington, Minn., hotel a few miles from the Met. In Minnesota "the Met" referred to the Twins' tinker-toy stadium, while in New York "the Met" was and remains both a palatial opera house and world-class art museum, which nicely sums up the high- and low-brow distinction between the two locales. New York invented baked Alaska and Eggs Benedict. Minnesota gave the world Tater Tot Hotdish and Cocoa Puffs.

"This place stinks," Martin famously said of the Twins' next home, the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, in 1985, after he had been rehired by Steinbrenner. "It's a shame a great guy like HHH had to be named after it."

And while the Dome was in fact named for the former vice president and not the other way around, that wasn't Martin's point. The Dome "should be banned [as] a Little League field," Martin said. "Why doesn't [Twins' owner Carl Pohlad] spend $100,000 and paint the ceiling so you can see the ball? What is he . . . a billionaire? Tell him they don't put pockets in coffins." This is another recurring theme, one shared over the decades by Twins fans themselves: that the team's owners—first Calvin Griffith, then the Pohlad family—were unwilling to shell out for high-priced free agents. Pohlad never talked, Steinbrenner never stopped talking, and their personalities embodied the ethos of their respective cities.

Steinbrenner said of the Twins' home: "What takes place in the Metrodome is not a ballgame, it's a circus. . . If I wanted my players to be Ping-Pong players I would send them to China to play the Chinese national team."

And while it's true that the Yankees had the greater history, and the more mythological Babe (Ruth over the Blue Ox, in a split decision), the Twins held the upper hand for a while, winning the World Series in 1987 and '91 inside their Teflon-coated circus tent. In 1998, in retribution, the Yankees traded for the '91 champs' leadoff hitter, Chuck Knoblauch, who had requested a trade to the Bronx. At last, the Yankees had a Twins' second baseman who sufficiently appreciated their pin-striped majesty, and the Bombers won the World Series the next three years, anchored by the only other Panamanian to make the Hall of Fame, closer Mariano Rivera, who has no known connections to the Stella D'Oro breadstick empire.

It was during this era, at the dawn of the new century, that the Twins-Yankees "rivalry" turned violent. When Knoblauch returned to the Metrodome on May 2, 2001, this time playing leftfield, closer to the drunks in General Admission than he ever was at the keystone sack, the faithful—penned behind Plexiglas—showered him with coins, trash and reasonably priced cylindrical sausages. (It was dollar dog night at the Dome.) The game was suspended twice, and Minnesota manager Tom Kelly trekked to the warning track to plead with fans, dozens of whom were ejected. Legendary P.A. announcer Bob Casey also scolded them, reminding them not that their drunken behavior was boorish and dangerous, but rather that, "This is an important game!" And it was—they all are against the Yankees. The Twins won 4-2, a small victory in the fight for respect.

That was the last year Minnesota took a season series from the Yanks. In the following 18 years the Twins have gone 35-87 against the Bombers, a .287 winning percentage, which extrapolates to a 46-116 record over 162-game season and the notion, fixed in the minds of most Minnesota fans, that the Yankees—like mortality or mosquitoes or road repair—are something to be surrendered to.

Of course, the Twins might yet avoid New York this postseason, but even an opening loss to the Astros in the ALDS would see them eclipse the Red Sox for the most ignominious postseason streak, though of course Boston has long-since vanquished its own ghosts from the 1980s and '90s with four World Series titles. To baseball's most famous curses—Bambino and Billy Goat—we might add Bunned Meat and Breadsticks, except that Minnesotans have seldom dealt in the supernatural self-pity, the emotional exhibitionism of Red Sox and Cub fans. The North Star State's attractions are less ostentatious, to say the least. New York City has the Statue of Liberty, lifting her lamp beside the golden door. Minneapolis has the statue of Mary Richards throwing her hat into the air on Nicollet Mall, as she did in the opening credits of The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

Mary's best friend on that show, set in Minneapolis, was the Bronx exile Rhoda Morgenstern, who once said to Ms. Richards: "You're talking about Midwestern love. I'm talking about Bronx love." Both are deeply felt but expressed differently. And while Bronx love is more demonstrative, Minnesotans are human, too, and any Twins games against the Yankees—or even a loss to the Astros, preventing such a matchup—will be no less painful for having been suffered in silence.

Steinbrenner and Pohlad and Martin and Casey have all shuffled off this mortal coil, and fewer Minnesotans remain who remember how this whole rivalry started, but the Twins (owned by the Pohlad heirs) and the Yankees (owned by the Steinbrenner heirs) will play on. As in the best (and worst) of feuds, the origins are forgotten but the animus endures. It would be a shame not to see them rejoin the battle in October.

Toward that end, the Twins in 2017 acquired ex-Yankee pitcher Michael Pineda, who went 11-5 with a 4.01 ERA this season, brightening prospects for a playoff run—at least until he was suspended on Sept. 7 for taking a banned diuretic. Minnesotans will be forgiven for suspecting he was a Trojan horse laced with hydrochlorothiazide, sent by the Bombers into Twins Territory (a fittingly more modest version of Red Sox Nation). At the very least, the righthander is the latest symbol of New York's dominion over Minnesota. Or perhaps another equine metaphor is more apt. The Twins have been a papier-mâché donkey, whom the Yankees intend to beat with a brass breadstick until every last piece of candy has fallen out. You say Pineda, I say piñata, but it's still too early—and far too interesting—to call this whole thing off.