Two Playoff Teams, Two New Stadiums and One Great Divide

This story appears in the Oct. 7, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Two maps tell the story.

First, John Schuerholz stared into a camera and stunned a city. Unflinching, the Braves' GM turned president, whose teams had won 14 straight division titles, explained to Atlanta baseball fans on Nov. 11, 2013, that the club was abandoning the area just south of downtown, its home since 1966. No longer would the Braves play at Turner Field, where skyscrapers looming over left center made it feel as if the entire city was watching. Instead, the franchise would build a stadium 14 miles north, in Cobb County. "This new ballpark," Schuerholz said of what would come to be called SunTrust Park, "will be in the heart of Braves Country."

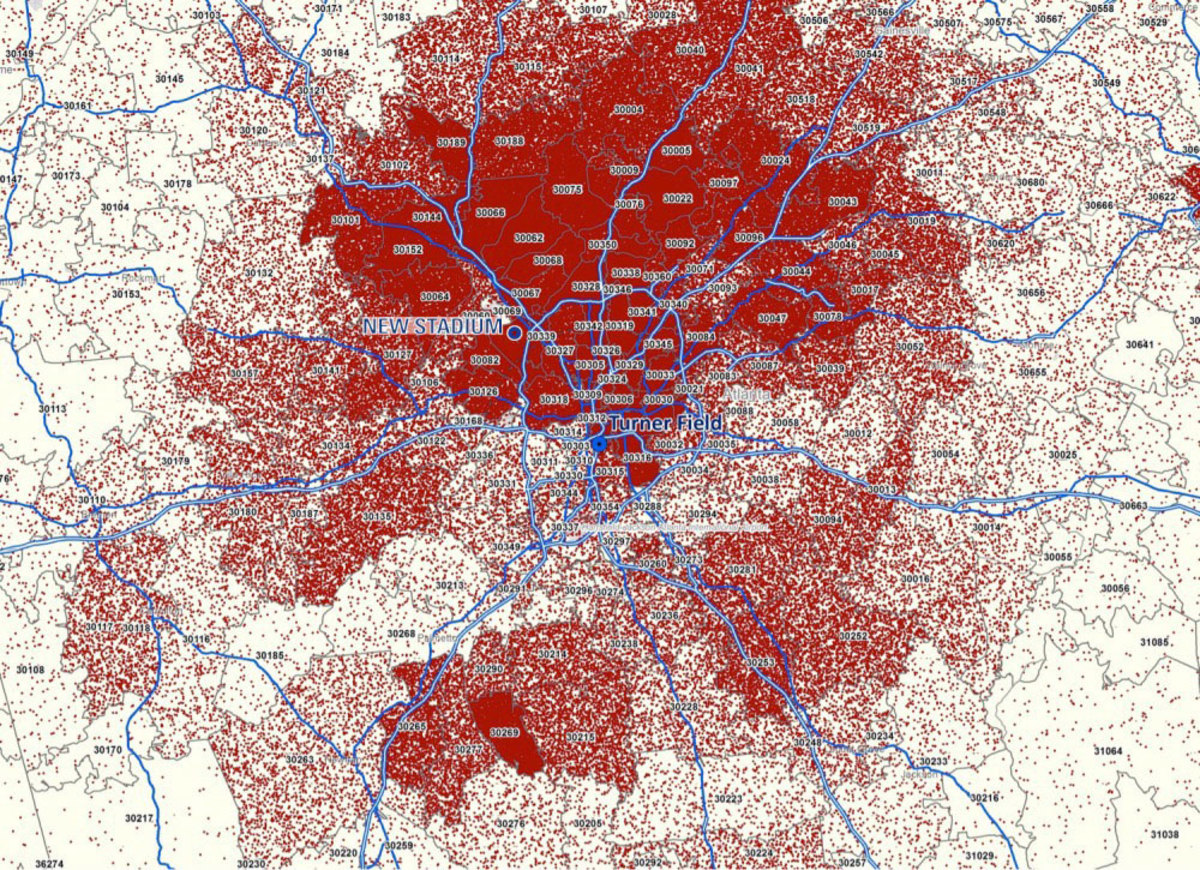

Accompanying the announcement, the team released a map showing where, precisely, Braves Country was—and, notably, where it wasn't. That view of the greater Atlanta area was speckled with red dots, each one indicating the home of a 2012 ticket buyer, including season-ticket holders. Only a smattering of red appeared to the east, west and south of Turner Field, while thousands of dots congealed into a ribbon above downtown that expanded into a wide swath in the half-dozen suburban and exurban counties to the north. The new stadium would be closer to the middle of that mass, which happened to embody an older, whiter and more conservative population than the city proper. Those northern suburbs were fast diversifying, yet many in Atlanta—particularly in its black population—felt slighted by the decision, their perspectives colored by decades of racial and political tension between city and sprawl.

Five months later MLS commissioner Don Garber, Falcons owner Arthur Blank and then-mayor Kasim Reed proclaimed in their own press conference that downtown Atlanta would be home to MLS's 22nd franchise, and the new club, Atlanta United, would take the pitch in 2017, the same year the Braves headed to Cobb. The soccer team would play in the same new $1.6 billion stadium the Falcons would soon call home, but United would be no afterthought. The facility would be designed to accommodate the beautiful game from the start. Pushing back against skepticism and pointing to an influx of young professionals near Atlanta's urban core, Blank assured MLS's leaders he could fill the massive venue, even in a market known for lukewarm enthusiasm toward pro sports. Reed boasted that his city's foreign-born (and, seemingly implied, soccer-loving) population was growing at the second-fastest rate in the U.S. Garber himself insisted these factors combined to make downtown an ideal MLS incubator. The city "embodies what we call a 'new America,'" he said, "an America that's blossoming with ethnic diversity."

Fast-forward five years, and Atlanta United's ticket-sales map, while not a direct inverse, is considerably more centralized than Braves Country (or even, says United president Darren Eales, a depiction of the Falcons' fan base). United, meanwhile, aided no doubt by winning the 2018 MLS Cup, has led MLS in attendance in each of its three seasons, averaging 53,003 fans in '19, among the highest in the world. This echoes the success the Braves found when they chased their audience to the north, the farthest any MLB team had ventured from its city center in 50 years. The Braves' average home attendance, aided too by on-field success, reached 32,779 fans this season, up 31% from their last year at Turner Field.

Both teams, with their concurrent seasons, have attracted a phalanx of fans despite appealing to markedly different demographics in the same metropolitan area. But those who study Atlanta's history and its evolving urban geography suggest the two franchises' parallel successes reflect a broader American fissure that has been widening for decades. A 2019 study at the University of Maryland found that geopolitical divisions within states are more prevalent now than at anytime since the years leading up to the Civil War—and Georgia, those researchers determined, was more polarized than all but one other state.

As a pair of talent-laden teams march to the postseason, might an unprecedented national bifurcation have found its way into Atlanta's sports venues, its precious few remaining patches of common ground? Could the brilliant and incongruous business strategies of the city's baseball and soccer clubs have been the inevitable byproducts of decades of disunion? "In retrospect," says Larry Keating, professor emeritus of city and regional planning at Georgia Tech, who has studied race, class and urban development in Atlanta for more than 30 years, "it was a predictable evolution."

While these are trends and not absolutes, Atlanta's denizens appear to be retreating in their leisure time to a pair of resplendent safe spaces. And many in those two thrumming crowds, only a dozen miles away from each other, seem eager to remain worlds apart.

Kevin Kruse, a Princeton history professor, understands better than most people where Atlanta's split started. His 2005 book, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism, traces the city's racial and political changes since the 1950s. While comparable trends occurred in a litany of municipalities, Kruse homed in on Atlanta in part to address the misleading moniker employed in the 1960s by mayor William Hartsfield: The City Too Busy to Hate.

That hopeful notion, Kruse has found, was ill-informed. The white population within Atlanta's city limits dwindled by more than 50% between 1960 and '80, as those who fled to the suburbs, Kruse writes, fought to stop contributing to the funding of shared public spaces—golf courses, parks, pools, schools—that they believed would be used by the inner city's African-Americans.

In 1965, five metro-Atlanta counties were asked to vote on a public transit system to link the city to the sprawl, and all but Cobb voted in favor. (Two more would back out in '71.) Here opposition was rooted in the notion that tethering white Cobb to black Atlanta would trigger an influx of crime in the area. Almost 50 years later the resultant bus and rail system, MARTA—which for decades has been referred to in certain racist circles as Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta—still doesn't pass through the county.

In 1975, Kruse writes, Joe Mack Wilson, a state representative from north of Atlanta, went so far as to point to the Chattahoochee River, which separates Cobb from the city, and tell a reporter that his constituents "wish they could build forts [on the river banks] to keep people from coming up here." Flash-forward to 2013 and Cobb County Republican Party chairman Joe Dendy echoed that sentiment, saying access to the new stadium was "all about moving cars in and around Cobb . . . where most Braves fans travel from, and not moving people into Cobb by rail from Atlanta."

Through all of this, the city has expanded and evolved. Since 2010, the 29-county metro area has experienced the fourth-largest population growth of any U.S. city, to nearly six million. And that expansion has seen new groups, including a vast black middle class, spill into Atlanta's suburban counties. In Cobb, for instance, nonwhites are expected to outnumber whites by '21. That shift, Kruse notes, has triggered many white families to move even farther from the city, to the metro area's exurban counties. (Meanwhile, a slew of young, white transplants are flooding the city center, further diversifying the mix—just the type of fan base United sought to court.) Indeed, the MLB club noted in the '18 iteration of its Braves Country map that the concentration of red has ticked even farther north and, says a team spokesperson, the northern metro area remains the team's "stronghold."

When Andy Walter saw the Braves Country map in 2013, it reminded him of other depictions of Atlanta that he'd seen in his work as an economic and urban geography professor at the University of West Georgia—particularly maps that delineated black and white, or rich and poor. Laid atop one another, all these maps seemed uncannily similar.

Beyond merely reflecting reality, Walter says, maps can actually prescribe meaning by calling attention to differences, which influences how people identify themselves and label others. "You can 'other' people," Walter says. "That's how identities often work. You figure out what you're not."

He even saw this in his own living room in Inman Park, where refurbished homes are packed tight and rainbow flags abound. When the Braves announced their move, Walter's wife, Katherine Hankins, a Georgia State urban geography professor who grew up an hour south of Atlanta and latched onto the Braves during their 1990s ascendance, declared she was boycotting the team. No more games on TV. No more muggy evenings under the stadium lights. Because of what decades spent digesting maps had told her about herself and her city, those 14 miles the Braves moved were saturated with meaning.

Katherine stresses she wasn't a baseball fan. She was a Braves fan. The team had been the vessel through which she felt connected to Atlanta—and now it planned to move to the "morass" north of the city, with which she didn't identify. "I felt abandoned," she says. "I thought: The Braves are dead to me. I'm having nothing to do with this team."

Were she to attend a game today, Hankins might see that disconnect embodied. Howard Evans, the 72-year-old president of the Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club, was at SunTrust Park on May 29 when the team announced it would host the 2021 All-Star Game. And he took note when Governor Brian Kemp, a Republican (who has been accused in the past of working to suppress the black vote), earned one of the loudest ovations of the day's speakers. "This is Republican territory," Evans says. "It's very red." (Keisha Lance Bottoms, Atlanta's sixth-consecutive black Democrat mayor, was greeted with polite applause at her first trip to SunTrust.)

To be clear: Residing in a suburban county to Atlanta's north is no indication of a right-leaning worldview, just as living downtown is no guarantee you're a liberal or of a minority. Furthermore, the Braves did not relocate to chase an ideology or a race. In fact, team execs spent the good part of a decade negotiating to stay in their longtime home. But that dialogue stretched across two mayoral administrations and slowed considerably when the city began hashing out a $200 million deal for what would eventually become Blank's football-and-soccer facility, Mercedes-Benz Stadium. "I don't think anybody thought the Braves would actually leave Atlanta," says Bottoms. "There was probably a bit of envy because the Falcons were getting a lot of attention—energy the Braves didn't get."

Ultimately the Braves secured nearly $400 million from Cobb County in a deal to build what would become the $672 million SunTrust Park, and they invested $700 million to develop an adjacent mixed-use development, now dubbed The Battery. With ample funding, full ownership of The Battery, infrastructure for traffic and parking demands, a fertile fan base north of the city and a chance to better accommodate the roughly half-million people who flood in from neighboring Southern states every season, the business argument for the Braves' move seems unimpeachable. Mike Plant, president of the team's development company, says, simply, "It's math."

According to Braves president Derek Schiller, the team knew well the civic and social implications of leaving the congressional district represented by civil rights hero John Lewis for one that had long been in white Republican hands. Schiller says he agonized over the decision. The Braves went so far as to consult with local African-American leaders, including Hank Aaron and his wife, Billye. And they studied Cobb's evolving demographics, noting the area's own burgeoning international and minority populations. "The perception is that Cobb County today is what Cobb County was 40 or 50 years ago," Schiller says. But "it's a misnomer. . . . We represent all of metro Atlanta, all of the South. We have to be open and welcoming to all people."

But intent and perception are often incongruous. Brian Jordan played for the Falcons from 1989 to '91 and the Braves across five years in the '90s and 2000s, and after growing up in Baltimore, he was surprised by how fervently Atlanta embraced an African-American athlete. Today he works as an analyst for local Braves broadcasts, which has him living in Roswell, 25 miles north of the city center. And the difference between the two places, in racial and cultural makeup, he says, is jarring—"like you're on the other side of the world." When the Braves left, many of his friends in Atlanta's black community were furious. "They took offense. No question."

"People felt like [the Braves] were abandoning the city," says Bottoms, who adds that it was "a slap in the face" when the team sought to bring along a statue of Aaron that had stood outside the Braves' two stadiums since 1982. (The statue ultimately remained by the former Turner Field, which has been repurposed into Georgia State's football stadium.) Three years after the move, Atlanta's mayor says she still hears people refer to the team derisively as the Cobb County Braves.

Still, she applauds the team for hosting nights dedicated to local HBCUs and for making efforts to reconnect with the African-American fans it may have lost six years ago. "There's no gain for us to see [the Braves] not succeed," she says. "It's time for us to heal."

Atlanta United's most loyal supporters pass the pregame hours under grimy city overpasses, on a wide swath of pavement set aside from a cluster of train tracks by chain-link fencing. The Gulch—a dystopian name for a grungy setting—is an unsightly urban ditch surrounded by concrete columns that hold city streets aloft. But it's teeming with life.

Stroll this lot, one block east of Mercedes-Benz Stadium, and Atlanta's essence is condensed into a few acres of asphalt. The music pouring from car stereos changes every few strides: Upbeat Latin pop blurs into country fiddling, then the thumping undergirding of a Southern rap song. Venezuelan flags yield to German flags yield to American flags. The scent of Mexican spices blends with the perfume of barbecue wafting off a neighboring grill.

This is all in vivid contrast to The Battery, with its careful planning evident throughout, where pop music flows through open spaces and fans dine in air-conditioned rooms, swaddled in soft booths. All of it evokes a theme park, a bubble floating free of the city around it, designed to keep you on site all day. The aesthetics—taupe brick; wide, clean alleys—mimic the upscale shopping centers peppering Atlanta's neighboring counties, the type of setting most Braves fans call home, akin to the purposely isolated enclaves the white flight generation carved out decades ago. (Indeed Braves data suggest little crossover with the United fan base.)

Of the 531 apartments erected on The Battery property (and sold by the team for $156 million), 97% are occupied. The allure? Meghan Bailey, a 31-year-old psychiatric nurse, has shared a unit at The Battery with her sister for two years. Beyond the proximity to the stadium, she loves that she can walk her dog at night without fear, a point she circles back to repeatedly as she nurses a margarita in a bar above rightfield at SunTrust. "We love it here," she says.

Cobb County Commission chairman Mike Boyce (R.) puts a finer point on it. "You can be here 24 hours a day," he says, "knowing you're going to be safe, no matter where you parked your car." Schiller gets at the same idea, framing the contrast between the old stadium—where crime rates were higher—and the new one this way: "Safe and secure. And welcoming. And friendly."

Kruse, the Princeton history professor, is blunt in his assessment of such feelings. "These ideas about downtown being a dangerous place are really about the people downtown," he says. For years he thought that "suburbanites want nothing to do with the city except to see the Braves." But today? "That last connection has been severed. I see this movement of the stadium as the culmination of white flight."

Meanwhile, the same area the Braves found inhospitable for their fan base has become fertile ground for United to grow their own. Jeff Larentowicz, who joined the club before its first season, says the electricity of a 55,000-fan frenzy at United's first home game eclipsed anything he'd experienced in 12 years in MLS. That frenzy hasn't relented, and today's crowd, players and execs say, reflects the city. "We could take a photo of any section of the stands, and it would be young, old, black, white, Hispanic, female, male," says club president Darren Eales. "Real diverse. A real microcosm of Atlanta."

Explaining the club's surprising popularity is complicated. Sure, winning has helped. Eales further credits the city's vast number of transplants—a recent study found 37% of the metro population hails from somewhere else—who may have arrived with a favorite baseball or football team but who latched onto United as a means of connecting with their adopted city. The team purposely focused its early marketing efforts inside Interstate 285, a ring surrounding the core of the metro area and home to a diverse population that, executives thought, might be thirsting for the type of communal experience United could foster. The club appealed to the city's famously vibrant African-American community by making hip-hop central to its in-game experience, recruiting prominent local rappers like Goodie Mob, 2 Chainz and Waka Flocka Flame to anchor pregame festivities. The city has helped United grow too, partnering with a nonprofit, for example, to build small soccer fields atop a pair of MARTA stations, providing easy access to the sport for newly enraptured inner-city youth.

While the team and its fans boast about diversity—the ideal is even prominent in several supporters groups' mission statements—the crowd Eales describes tends not to include Atlantans from the poorest, predominantly African-American neighborhoods just west and south of downtown. Keating, a longtime city planner, worries those residents will soon be priced out of the area. Already there are plans to transform the Gulch into a $5 billion mixed-use development, beginning next year, and Blank's foundation has pledged $30 million to revitalizing the surrounding neighborhoods. United, meanwhile, is collaborating with supporters groups to replicate the organic atmosphere of today's Gulch in an adjacent lot.

Curtis Jenkins is the president of one such group, Footie Mob. He's also a native of the East Point area, southwest of downtown, with its 76% African-American population. He says the club is starting to gain a modest foothold in places like his hometown, but that support is minimal compared with the enthusiasm among Atlanta's multi-hued young professionals. Still. "You could've told me this would happen," he says, motioning to the hundreds of black, white and brown faces at one recent Footie Mob pregame party in the Gulch, "and I'd laugh at you."

At an Aug. 11 match against New York City FC, members of one United supporters group marched toward Mercedes-Benz Stadium carrying signs decrying gun violence and fascism. And while a good number of those banners were eventually confiscated (per a since-changed league policy), United supporters tend to feel at ease inside, or in the Gulch, surrounded by people who share their beliefs. "I kind of live inside the perimeter bubble"—a nickname for I-285—says David Prophitt, the president of All Stripes, an LGBTQ United supporters group. "It's much safer."

For a few overlapping hours on June 1, two polar-opposite fan bases urged their respective teams forward, toward promising fall playoff runs. In Cobb County the Braves wrapped up a 10-5 win over the Tigers at around 7 p.m. (Three months on, they would win the NL East.) About an hour later United closed out a 2--0 victory over the Chicago Fire. (They're now in second place in the Eastern Conference, with one game left.)

After the MLS match, diehards streamed up from their seats to a wide atrium at Mercedes-Benz Stadium's east end, which rests under a massive window framing the Atlanta skyline. They sang and danced and beat drums and waved flags before finally spilling out onto a plaza where a massive rainbow scarf had been draped over the neck of a 41-foot-tall statue of a falcon.

Had the Braves not left downtown, supporters in red-and-black United jerseys might have been packed in tight on nights like this with baseball fans in navy Braves T-shirts, at bustling bars and on sweaty train rides home. They might have traded smiles and congratulations. Maybe raised glasses. Maybe shared a fleeting moment of commonality with someone who looked different or believed in something else.

Instead, distance. If you'd lingered in The Battery for a beer or a burger that night, you wouldn't have heard United fans drumming far off, wouldn't have seen Atlanta's long spine of skyscrapers. Nor would the last stragglers downtown have seen any glimmers from the bright banks of stadium bulbs out in Cobb County. Even for the light, the gulf proved too vast.