Tom Seaver and the Enduring Hope of the 1969 Mets

Editor's note: Tom Seaver died on Aug. 31, 2020, at age 75. This story was written in October 2019.

Tom Seaver looked out the window of his home office in Calistoga, Calif., his back to baseball and the past.

Behind him on this day in May 2017 were photographs and totems of a career that in both form and substance stands as the closest man has ever come to mastering the art of pitching. There was a shot of young Tom standing with Gil Hodges, not only his manager with the Mets but also a fellow Marine and a second father to him. There were his three Cy Young Awards, from 1969, '73 and '75.

Body and coif still robustly thick at age 72, Tom peered ahead, to his grape arbors on Diamond Mountain, with Mount St. Helena looming in the distance. Dear God, he could not believe how lucky he was.

One day back when Tom was at the height of his pitching prowess, his brother-in-law asked him, "What will you do when you're done?"

Tom shot back an answer without even thinking, one of the few times in his life when he moved a piece on his chessboard without meticulous study.

"I'll go back to California and grow grapes."

With that quick answer Tom Seaver cast his lot.

And in 1998 he found it on the sunny western rim of the Napa Valley—a 116-acre slice of earth as beautiful as heaven allows. It was covered with trees then. Tom saw how it faced south, tilted toward the Sun, and how it rested several hundred feet above the valley, less troubled by fog. The soil was volcanic, porous, perfect for cooling under all that sun and for growing small, intensely flavored Cabernet grapes. He bought the land and, with dirt under his fingernails, has tended to it and his 3 1/2-acre winery ever since.

He hired a friend from Massachusetts, Kenneth Ken-Sin Martin Kao, to create the home on the lot where he and his wife, Nancy, have lived. The son of a minister and teacher, Kao designed in the spirit of his passions: bike racing, boat building, Frank Lloyd Wright, passive technologies, the environment. The Seaver house quietly blends into the landscape, without calling attention to itself or the fame of its owner.

Four friends stood with Seaver in his office that day: Bud Harrelson, Jerry Koosman, Art Shamsky and Ron Swoboda, teammates from the 1969 world champion Mets.

Left unspoken was the knowledge that they might never again see one another like this. And last March, less than two years later, the Seaver family announced that Tom was suffering from advancing dementia and "has chosen to completely retire from public life."

We love sports for many reasons, but none more than Possibility. What might happen in the unscripted world of competition? And no team better defines this inherent appeal than the 1969 Mets. They are the Patron Saints of Possibility. In a year when man walked on the Moon, the Jets upset the Colts in Super Bowl III, the Beatles released Abbey Road, the first U.S. troops withdrew from Vietnam and Woodstock rocked, the Mets carved a unique place in the pantheon of what's possible. They leveraged holistic teamwork into one of the most unlikely championships ever seen or even imagined. Fifty years ago this month, and 100-to-1 long shots when the season began, New York beat the mighty Orioles in five games to win the World Series.

***

Because of the granite reliability of his pitching and his steady persona in a turbulent time, Seaver is the touchstone to that 1969 magic. The numbers speak to the passage of time. He was 25-7 with a 2.21 ERA. As the young Mets ran down the more seasoned Cubs in the National League East, Seaver went 10-0 with a 1.34 ERA in his last 11 starts. He was nearly perfect in six September turns: no home runs, no stolen bases allowed, no losses and no relievers.

Astoundingly, Seaver was 12-5 that year when New York scored just three runs or fewer (.706), the highest winning percentage in such low-scoring games in the live ball era (minimum 14 games since 1920). No better testament to his will exists than this: Seaver pitched the ninth inning 18 times and never surrendered a run or even an extra base hit. Seaver and Virgil Trucks ('49) are the only starting pitchers to do that.

Seaver, Harrelson, Koosman, Shamsky and Swoboda all were between 24 and 27 that year. When they reunited in 2017, those young boys of summer knew mortality too well. Harrelson was in the early stages of Alzheimer's. Seaver had battled Lyme disease, and now word had spread among his former teammates that his cognition was waning. Shamsky wanted to write a book about that team. He knew time and memory were slipping away. "I would say more books have been written about that team than any team in history," Shamsky, who published After the Miracle (coauthored with Erik Sherman) earlier this year, says. "We wanted to write a book not about the game, but about the relationships we developed. We already lost 10 members of that team. I knew I wanted to talk to Tom, but I didn't want to do it over the phone. I said, 'We've got to do it face-to-face.' "

Says Swoboda, "I wish none of this was happening: Bud Harrelson, Tom . . . two of the smartest guys on the team. God, it's an awful thing."

Shamsky first telephoned Seaver.

"Look, talk to my wife," he said. "She's making my schedule."

Tom put Nancy on the phone.

"There are good days and bad days," Nancy told Shamsky. "I can't guarantee you anything. You could get all the way out here and he might not feel well that day."

Shamsky and the teammates coordinated their trips for a weekend: Shamsky and Harrelson from New York; Koosman from Wisconsin; and Swoboda from Louisiana. They landed late on a Friday afternoon in San Francisco, intending to drive up that day. Shamsky phoned Nancy. The news was bad.

"He's not feeling great," she said.

Shamsky's heart sank. He knew that left only Saturday before their return flights on Sunday.

The next morning, a fearful Shamsky called Nancy for the verdict. "You lucked out," she said. "Get over as soon as you can."

***

The marble not yet carved can hold the form of every thought the greatest artist has.

—Michelangelo

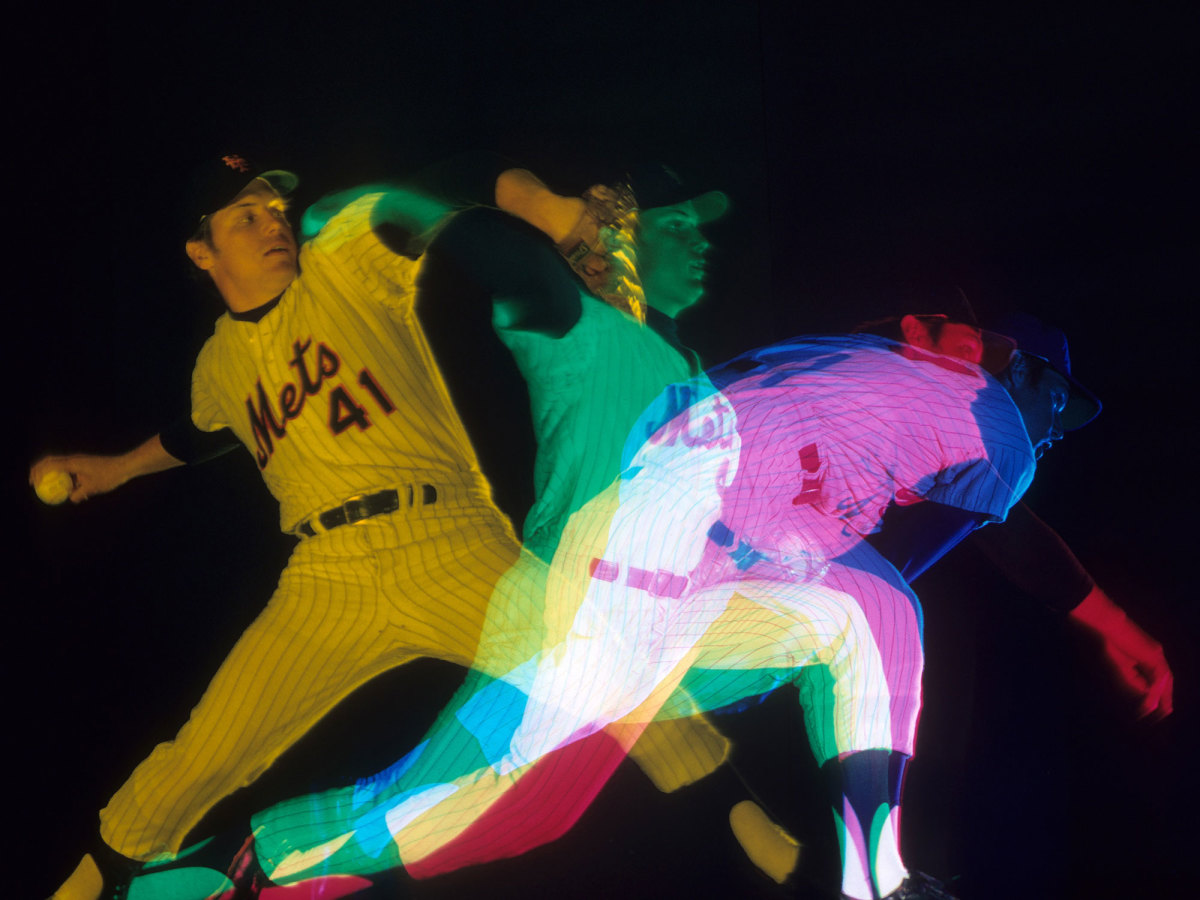

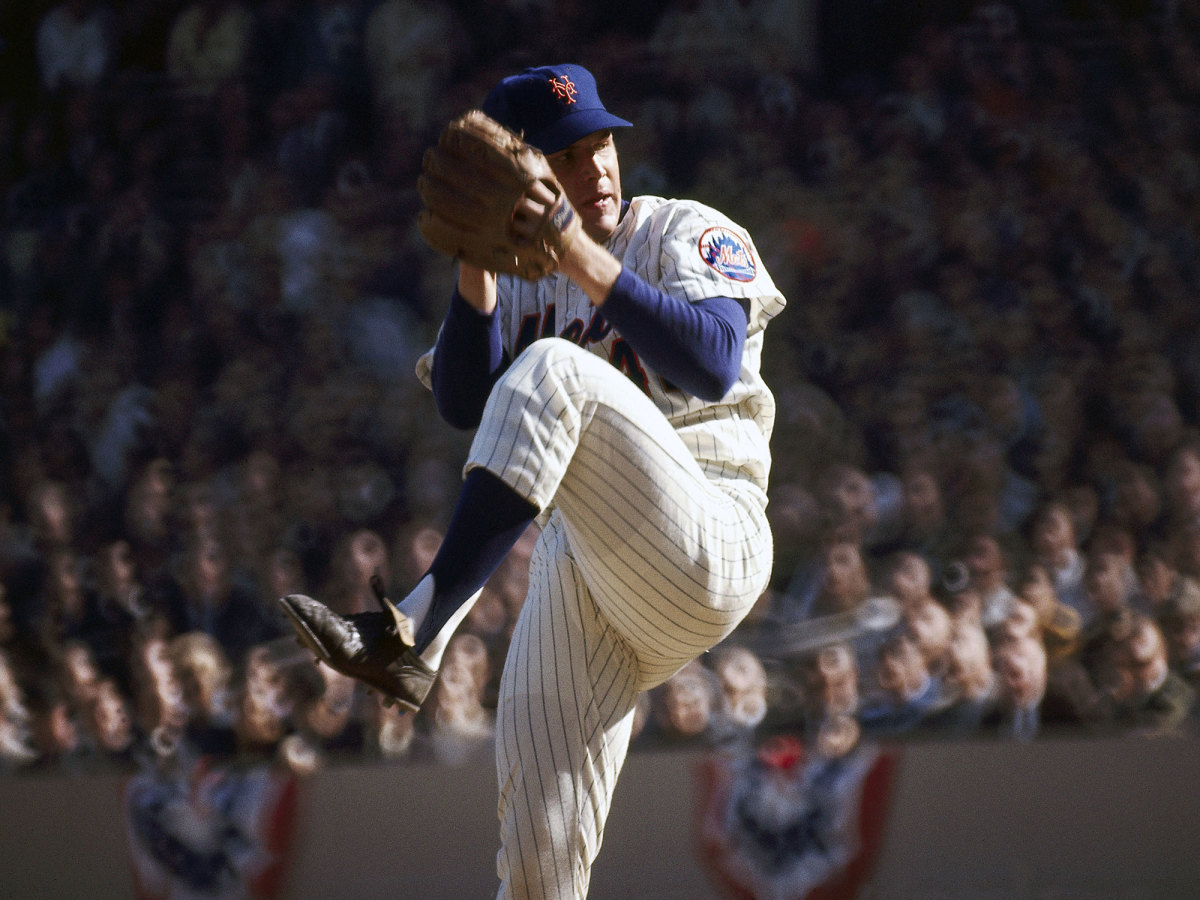

As a pitcher, in form and function, Seaver was impeccably carved. When longtime major league player and manager Harry Walker taught pitching, he used still images of the righthanded Seaver as his template. He had the leg strength of a running back, the balance of a ballet dancer and the will of a marathoner. The hands over the head, the "drop and drive" of the lower body, with legs, hips and glutes firing like cannons, the back knee hitting the ground hard enough to need a pad there under his uniform pants, the arm bursting through last . . . so familiar. . . perfection on repeat. Watching Seaver uncoil was like standing next to the train tracks as a 200-ton diesel locomotive roared by, the speed and power leaving a wake of awe.

"When he showed up in 1967 [in the big leagues] he was the same guy," says Swoboda. "He was the same Hall of Fame guy, same stuff, same bearing on the mound. There was no break-in period. He came out of the box Tom Seaver."

Tom Seaver had power and command in elite portions. He said in 1969 that he threw seven pitches: three types of fastballs ("It sinks, sails or runs in"), two curveballs (one slow, one fast), a changeup and a slider. All behaved as well as children on Christmas Eve. He once said if he threw 125 pitches in a game all but about a handful ended precisely where he intended. So good was Seaver that Reggie Jackson once said of him, "Blind men come to the park just to hear him pitch."

Seaver was the happiest accident that ever happened to the Mets. Growing up in Fresno, Seaver didn't make his high school baseball team until his senior year. He went to Fresno City College, where he was a good pitcher but nothing special, then transferred to USC, where he blossomed. In 1966 the Braves gave him a $51,500 contract, but commissioner William Eckert nullified the deal on a technicality: College players weren't eligible to sign once their seasons had started. (The Trojans had played two exhibition games.) Eckert announced a lottery for Seaver. Any team willing to meet the $51,500 bonus price could enter. Only three other teams did: the Phillies, Indians and Mets.

On April 3, 1966, Eckert pulled the Mets' name out of a hat. Losers of no fewer than 109 games in each of their four years of existence, the Mets finally won something. They literally hit the lottery.

A year later Seaver was in the big leagues. He won 16 games and the Rookie of the Year award, then another 16 in 1968, when ninth-place New York had a very modest 73-89 record—the best in club history.

That offseason Seaver went back to USC to complete his degree in public relations. Mets GM Johnny Murphy signed him for $40,000, making him the highest-paid player on the team, and told other clubs that Seaver and lefthander Koosman were "the untouchables."

On March 18, 1969, Seaver told reporters, "I might be a supreme optimist, but I think we have a good chance to be in the World Series."

By mid-June the Mets actually had a winning record (29-25) but trailed manager Leo Durocher's Cubs by 8 1/2 games. "We've got the best pitching in the majors," Seaver said the day before a start at Dodger Stadium. "I think our pitching will hold up better than Durocher's. And it gets hot in Chicago in the daytime in July and August."

Seaver beat Don Sutton the next night 3-1. The Mets would go 71-37 from that game on. They won in such improbable ways, they embarrassed magicians. They took both ends of a doubleheader 1-0, with each run driven in by a pitcher. They struck out 19 times and made four errors and won. They won when Hodges put the hit-and-run on with the bases loaded; the runner at third, Cleon Jones, sprinted so hard that the batter, Jerry Grote, had to check his swing for fear of maiming his teammate. He hit a bloop over the head of a first baseman for a three-run double. Of course.

Three years earlier Time asked in a famous cover headline, Is God Dead? By October, Seaver had an answer.

"God is a Met," he said. "I heard that somewhere. Now I believe it. Don't you believe it? God is alive and living in New York, and I know who's paying his rent."

***

Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment, that was known as Camelot.

—Lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner

One week after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, his widow, Jackie, told Life that at bedtime she often would play the Broadway recording of Camelot on an old Victrola. The song he loved best, she said, was the last one on the record. Those lyrics and the couple came to define that small window in history when hope abounded.

Six years later Jackie, dressed in a "white sweater and brown miniskirt" (news reports in those days customarily described a woman's clothing); her second husband, Aristotle Onassis; and her children, John and Caroline, watched the Mets host their first World Series game. Other celebrities in attendance at Shea Stadium included Pearl Bailey, Jerry Lewis, Ed Sullivan, Mayor John Lindsay and, yes, Nancy Seaver.

Tom and Nancy created a baseball Camelot. They were the couple atop the wedding cake: handsome, fashionable, smart and in love. Super Bowl-winning Joe Namath was threatening to quit football and was running a notorious bar in New York City. (National League president Warren Giles issued a directive in June asking players to stay out of Bachelors III.) Slugger Ken Harrelson cut a divisive figure with his wild outfits, contract demands and controversial book. Mickey Mantle had just retired.

Tom and Nancy gave Americans torn by the turbulence in sports and society a safe harbor. Newspapers knew the appeal of baseball's First Couple, and they invariably reported how Tom and Nancy looked and what they wore. The New York Daily News in April: "With brown hair falling boyishly over his forehead and apple cheeks aglow, Tom Seaver doesn't look old enough to cuss." By June the News was calling him Mr. Dreamboat.

The Fresno Bee in June described Nancy as "the wide-eyed 5-6 blond who has those bathing suit measurements."

Nancy Lynn McIntyre had been a pep girl and diver at McLane High in Fresno. Tom went to Fresno High. Nancy watched him play basketball then—Seaver was all-city in that sport, not baseball—but he made no impression on her. "He was only 5' 10", she once explained. Upon graduation Seaver spent the next year in the Marine Corps. There he grew into a man. When Nancy was attending Fresno City College and saw Tom again, she was smitten.

"After Tom finished his duty in the Marine Corps, he was 6' 1 and it was a different story," said Nancy, who according to The Fresno Bee was "the campus queen and came within a judge's wink of making All Miss Fresno County."

After the Mets won the lottery they assigned Seaver to the Triple A Jacksonville Suns. Tom and Nancy had been considering marriage after that season, but Nancy, after consulting with her parents, decided it was best if they wed quickly. So she hopped a plane to Florida and they were married in June 1966 on the afternoon of a night game in between his starts. The newlywed pitched two days later. Seaver gave up four runs, made two errors and was knocked from the game in the fourth inning.

Arriving in New York the next season, Tom, Nancy and their French poodle, Slider, quickly became the darlings of the press, especially because Nancy was such a conspicuous cheerleader for her husband. Once in 1967, Seaver was hit on the right elbow by a pitch from Dennis Ribant of the Pirates. Nancy waited nervously outside the New York clubhouse. A reporter she recognized walked out.

"The right arm," Nancy said. "Why couldn't it have hit him in the head?"

On April 20, 1969, returning late from a trip to St. Louis, Seaver drove his brown '68 Porsche home to Bayside, Queens, and parked it on the street. When he awoke the next morning Nancy asked him, "Where's the car?"

"Right in front of the house, where I parked it."

"No, it isn't."

Seaver looked out the window. There was no Porsche.

"What the hell," Seaver said. "As long as nobody steals you or the dog. The car is just a piece of tin."

On Aug. 31, 1969, Parade magazine published a story from Tom under the headline, WHAT IT'S LIKE TO HAVE MY WIFE WATCH ME WORK. It was a love letter shared with millions.

"My wife is extremely important to me in my baseball career," he wrote. "I often look up at Nancy, not only when I'm pitching but when I'm in the on deck circle waiting to bat. Just a glimpse of her sitting in the stands gives me a great deal of encouragement. I'll tip my cap to her and she'll tip an imaginary cap back, letting me know there is something extremely personal between us no matter what the outcome of the game. Baseball is my entire life, but I could never play this game if it were not for my wife."

Seaver grew up studying the humble, understated brilliance of Sandy Koufax and Hank Aaron. His father, Charlie, a vice president at Bonner Packing Company, was the 1933 California amateur golf champion and a Walker Cup member who showed Tom how to compete with honor at Sunnyside Country Club, just down the street from the Seaver home on East Rancho Drive. Tom was fiercely proud of his military training on the half-million acres of Marine Corps Base, Twentynine Palms, Calif. The discipline he learned there, he said, would help him become a better pitcher. He embraced the all-American image.

A reporter asked Seaver if he ever had trouble with anyone. Yes, he replied: Ralph Houk, the Yankees' manager. Seaver explained that in 1967, he had stopped at Toots Shor's, the famous sports hangout, after the banquet in which he received his Rookie of the Year award. It was 1:30 in the morning when Houk saw him there.

"You'll never be a big league pitcher keeping hours like this," Houk snarled.

"If you had 25 players like me," Seaver snapped back, "you wouldn't finish 10th."

***

The events of life are not so important. The moments are essential. It is all about relationships.

—Carol Howell, Let's Talk Dementia: A Caregiver's Guide

It was a go. The teammates folded themselves into a car and pointed it toward Diamond Mountain. Harrelson, the plucky whippet of a shortstop, had been Seaver's roommate and dear friend. In his condition, he had been accompanied to California by Shamsky, the witty first baseman-outfielder who hit a pinch-hit, three-run homer off Seaver in 1967 as a Red, then dared not mention it to him over the next four seasons as his teammate. Koosman, the broad-backed Midwesterner, was the southpaw complement to Seaver in the rotation. Swoboda was the brash, ne'er-do-well rightfielder who became a productive role player in Hodges's platoon system.

Koosman and Swoboda, as if picking up where they left off 50 years earlier, when Vietnam divided dinner tables and clubhouses, immediately fell into heated political debates in the car, knowing they would have to table the arguments once they reached Seaver's house.

"Koosman is just a joy," Swoboda says, "when he isn't burying you in über-right-wing crap.

"I didn't run or hang out with Tom [in 1969]. I wish I would have. I was a guy who could find various ways to piss off Gil Hodges. All Gil wanted you to do was act like an adult and make you the best player you could be and help the Mets win ball games. I could do some of it some of the time, not all of it all the time like Seaver. Seaver was so focused and so organized in the way he approached things."

On that Saturday in May 2017, Tom and Nancy greeted the 1969 Mets at the door of their house. Seaver looked good. Robust. Healthy. They hugged. He gave them a tour of the home. Later they would drive to a restaurant for a long lunch.

They shared some wine and they swapped stories about 1969 in the unique intimacy of teammates. These tales, forged in the battles of youth, are the mortar of friendships. They linger not as stored memories, like dusty photographs in a shoe box, but as elements of our very being, like wrinkles and scars. They are not just part of what we did. They are who we are.

The five teammates spent almost nine hours together. Seaver repeated himself with a few stories about Hodges or Rube Walker, the team's wizard of a pitching coach, but that was the only sliver of a sign that something might be amiss in that famously studious, analytical head.

The highlight of the day was when the teammates walked the vineyards with Tom and his dogs, as Seaver does every day. It was a brilliantly bright and warm day, the Cabernet grapes tilted toward the nurturing sun.

"It was a pretty spectacular place," Swoboda said. "He looked good and sounded good. It was so much fun because Tom was all there."

***

Yesterday I got a card in the mail to sign. I still get them all the time.

— Jimmy Qualls in 2016, to the Herald-Whig, Quincy, Ill.

Jimmy Qualls had 31 hits in his major league career. He is famous because of only one of them.

At 7:30 a.m. on July 9, fans began lining up at Shea for tickets for the 8 p.m. game against first-place Chicago, which led New York by 4 1/2 games in the NL East. By the time Seaver threw the first pitch, thousands still were lined up in vain past the elevated train station next to the stadium. Hundreds more nearly stormed the press gate to see the phenomenon that was Seaver and the Mets. A crowd of 59,083 people did squeeze into the joint, including 7,056 Midget Mets, part of the team's youth fan club. In Wallkill, N.Y., town administrators were fighting the idea of this festival called Woodstock, and at Cape Kennedy in Florida, Apollo 11 sat one week from its launch. But on this night Shea Stadium shook with enough noise and meaning as to be the center of the universe. As each inning went by without a Cub reaching base, Seaver and the crowd grew stronger, a symbiosis of belief and will that was visceral.

"My heart was beating so much and the feeling was almost out of my arm," Seaver said after the game.

Harrelson was watching at a bar in upstate New York, where he was serving a short stint in the Army Reserve at Fort Drum. As Seaver walked to the mound for the ninth, Harrelson, bursting with pride, turned to someone standing next to him and couldn't help but say, "Hey, I know him. I know Tom Seaver. Tom Seaver is a friend of mine."

Twenty-five up, 25 down. Two outs from a perfect game, Seaver looked in at Qualls, a 22-year-old centerfielder the veteran-loving Durocher put in the lineup for one of only 28 starts that year. Seaver's father and Nancy ("wine-colored dress") watched nervously from the stands.

Seaver threw a fastball, aiming low and away. It was one of his rare misbehaving children, staying over the middle of the plate. Qualls hit it firmly and cleanly into centerfield for a single.

"With a guy like Seaver," said Grote, his catcher, "you don't second-guess. He throws the type of game he wants to throw."

Seaver had poured so much into this 4-0 victory that the hit "felt like somebody opened a spout in my foot and it all ran out of me, the pressure all ran out." (In fact, Seaver would come away from that game with a tender shoulder; he went 1-4 in his next five starts.)

"He'll probably never be that fast again as long as he lives," Durocher scoffed, "and if he pitches like that every night, he'll never lose a game."

After the game, Nancy ran into Tom's arms, crying.

"Don't cry. We won the game," he told her, "and I still had a shutout."

Nancy looked at him and laughed through the tears. She made Tom laugh.

"It was the first time I laughed since he got the hit," Seaver said.

Headline in the Daily News the next day: NANCY SEAVER CRIED SOFTLY IN 9TH.

A baseball career can be like a beautiful sailboat. You can attend meticulously to it, and yet ultimately where it goes can turn on the whims of tide and wind. The organization, teammates and especially the manager and coaches a player draws will all affect his course. Seaver may have been so good as to be impervious to such influences. That he fell in with Hodges, Rube Walker and the Mets put the wind surely at his back.

New York traded for Hodges in 1967, a move Murphy, the GM, called "the first big turning point."

"It's time, I think, we did something about that clown image of the Mets," Hodges said when he was hired.

He banned poker playing, instituted a curfew, put controls on drinking and fined players $25 a pop for mental mistakes on the field.

"I think Tom looked at him as a father figure," Shamsky says. "They shared a lot of common things—the way they approached the game, they were ex-Marines. . . . We all to a person respected the man as much as you could respect a man. Tom had a personally close relationship with him."

Hodges brought with him as his pitching coach an old Brooklyn Dodgers teammate, Walker, then 43, the catcher who called the fastball that Bobby Thomson hit for the Shot Heard 'Round the World in 1951. Until '68, only one pitcher had ever made 30 starts in a season on four days' rest—one more than norm then (Jim Maloney in '63). But to protect Seaver and Koosman, as well as up-and-comers Nolan Ryan and Gary Gentry, Hodges and Walker used their young starters in a groundbreaking five-man rotation in '68 and again for most of '69.

Moreover, the coach instituted Walker's Law: No Mets pitcher was allowed to throw a baseball at any time, even for a game of catch, without Walker's permission. (Seaver, Koosman and Ryan would combine to throw 14,008 innings over 66 seasons; Gentry threw 902 2/3 in seven.)

Down the stretch in 1969, Hodges and Walker took the reins off. Seaver and Koosman, sometimes pitching on short rest, started 24 of New York's final 56 games. The Mets went 20-4. They blew past a wheezing Cubs team to win the division. By then Neil Armstrong had walked on the moon and man needed a new boundary to cross. A Mets world championship would do.

"[Tom] was moving toward superstardom, but you didn't get that vibe from him," says Swoboda. "[First baseman Donn] Clendenon would never have put up with it, anyway. He was a clubhouse lawyer and eventually passed the bar. Ron Taylor was an engineer working on a medical degree.

"We were a lot of different people. Guys from the South, black guys, California guys, us East Coast guys who didn't know from s---. It was such a wonderful romp."

In The New York Times in September, sportswriter Leonard Koppett gauged the heart of this team better than an EKG, noting that 22 Mets had at least some college education and 21 of the 27 players used were between 21 and 28 years old. "As baseball teams go," he wrote, "these Mets are remarkably free of cliques and rivalries, and exceptionally in tune with the larger world of their day."

"A key figure in this respect is Tom Seaver, whose leadership by example is regarded as a major force in the club's maturation. He is open, alert, lively, kidding everyone yet serious about his work, competitive and emotional and natural. Such a man is an asset to any club, but when he is also the most talented and effective player the effect is magnified."

***

That guy believes in elves.

—Orioles third baseman Brooks Robinson, before Game 1, laughing at a writer who picked the Mets to beat Baltimore in the World Series

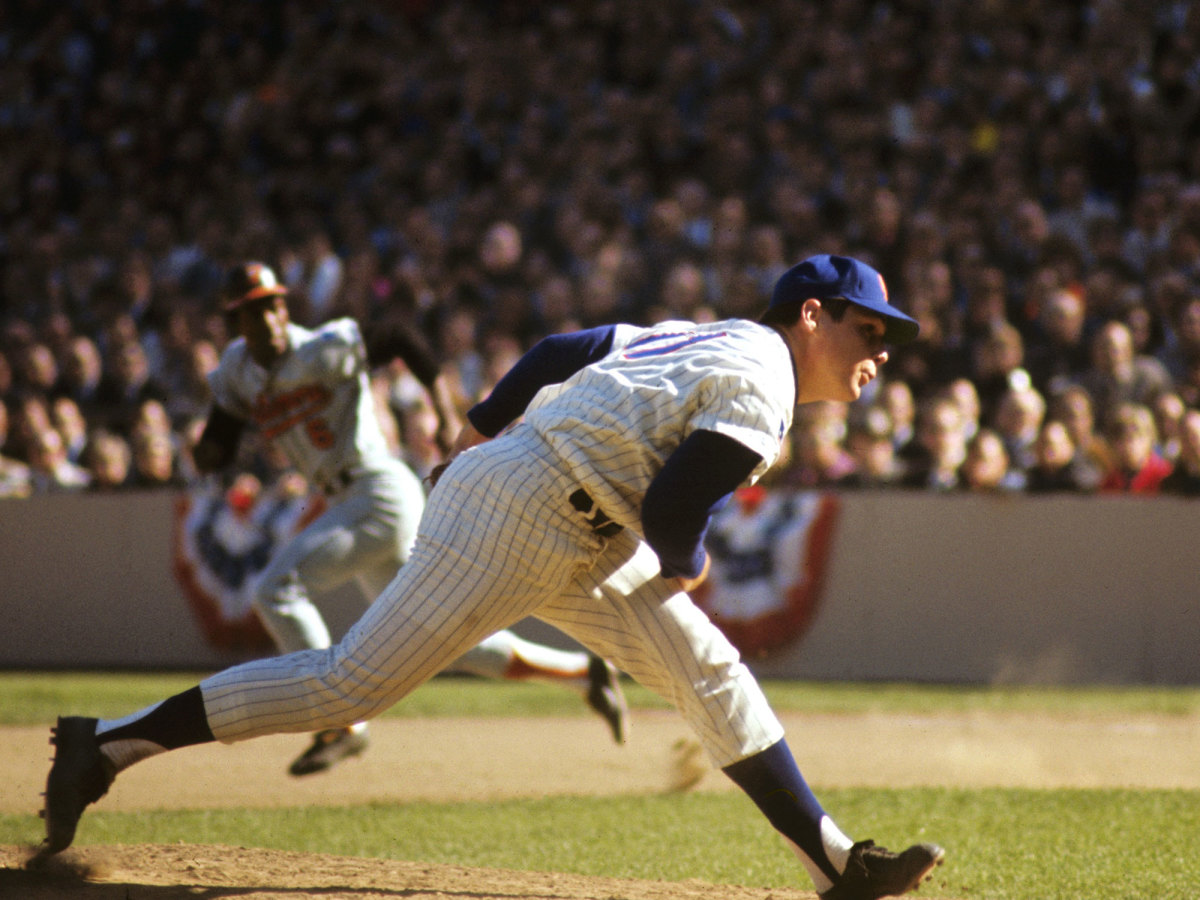

Seaver would run every day between starts to keep those hydraulic pistons that were his legs pumping strong. But after he beat the Braves 9-5 in Game 1 of the NLCS—in the first year of an extra round of the playoffs, New York would complete a three-game sweep of Atlanta—Seaver strained a leg muscle shagging flies and had to take off three days from running before Game 1 of the World Series. He lost 4-1 in Baltimore, allowing three runs in the fourth inning.

"I just ran out of gas," he said.

The Associated Press assigned a reporter to watch the game in the stands with Nancy ("stylish green cap that matched her pants suit"). "He had a good fastball but he just didn't have the curve," Nancy said. "And he must be awfully hungry. We didn't have any breakfast because the lines in the dining room were too long."

The reporter followed Nancy back to her hotel room and took note of how she dabbed at her eyes with a tissue: "Any other 24-year-old who so much resembles a Miss America and looks so vulnerable might have let the tears come. But Nancy Seaver has too much poise."

Seaver took the ball again in Game 4, on short rest, with the Mets up 2-1. Near the dugout at Shea, so many autograph seekers swarmed around Nancy ("brown knit pants suit, no coat," shivering as daylight expired) that the Mets had to summon security to control the crowd.

Tom held a 1-0 lead in the ninth when Baltimore put runners at first and third with one out. Hodges walked to the mound in that slow Indiana gait, fists tucked into the pockets of his jacket, with a grim, dark-eyed "wait-til-your-father-gets-home-from-work" look your mother warned you about. "If the ball is hit back to you, go to the plate if you can," Hodges told Seaver. "We want to stop that run from scoring. How do you feel?"

"I'm running out of gas," Seaver said, "but I still have a few pitches left." There was no way Hodges was taking him out of the game.

Robinson, the All-Star who didn't believe in elves, smashed a line drive to rightfield. Swoboda broke toward it. Each day Swoboda would work on his defense with coach Eddie Yost. He never took fly balls. He always took line drives and ground balls from 150 feet away—the hard stuff. Teammates and coaches always kidded Swoboda about his goofy ways. Bullpen coach Joe Pignatano used to tell him, "Don't think, Swoboda. You'll only hurt the team."

But with these drills, "I figured out how to be a better outfielder," Swoboda says.

He dived for the ball, a choice Orioles slugger Frank Robinson later called dumb because it risked having both runners score. But Swoboda snagged it for the second out. One run, not two, scored.

Seaver went back out for the 10th. Again, two runners reached with one out. This time Walker ambled to the mound. "I'm getting tired, but I can continue," Seaver vowed. He induced a fly ball and then, with his 150th pitch on short rest, and working his 296th inning of the year, he struck out Paul Blair.

Mets magic finally showed up in the bottom of the 10th with another one of those Scotch-tape-and-bailing-wire rallies: a pop fly lost in the sun for a double, followed by a bunt, which the pitcher threw off the wrist of the runner at first for a game-ending error. Of course.

Seaver covered 10 innings without allowing an extra-base hit. Only two pitchers ever had won a World Series game that way: Christy Mathewson in 1913 and Carl Hubbell in '33. Nobody has done it since Seaver.

Seaver and Koosman started six of the Mets' eight postseason games, including complete-game victories over Baltimore in Games 4 and 5. A couple of hours after the clincher, a 5-3 win at Shea, Seaver and Gentry left the champagne-soaked clubhouse and headed out toward the field. They felt a pull to go back to the pitching mound, an almost sacred physical place for them, the epicenter of everything that happened in 1969, and give thanks.

"We just wanted to see it or walk on it once more," Seaver said then. "You know, like when nobody was around or making a big fuss."

Seaver climbed the dugout steps to the field. His shirt was open and wet, and he was wearing no shoes—only his baseball socks. When he and Gentry made it to the mound, they were not prepared for what they saw.

"By the time we got there, it was too late," Seaver said.

Thousands of fans had stormed the field after the last out, and as if to require physical evidence that the Mets really did win the World Series, they grabbed fistfuls of grass and dirt. Most of the mound where Tom Seaver did some of the best work in the annals of pitching was gone.

A few hundred fans still milled about, not wanting the moment to end. When they saw Seaver they let up one last, loud cheer. Seaver smiled.

"You deserve some congratulations too," he told them. "You people are amazing too."

***

Now available: Tom Seaver, America's top athlete and sports personality, plus Nancy Seaver, Tom's lovely wife, for those situations that call for young Mrs. America or husband-and-wife sales appeal."

—Newspaper ad, placed one week after the World Series by Seaver's agent, Frank Scott

Tom and Nancy, like Jack and Jackie, aglow in beauty and youthfulness, and now with success confirmed upon them, captured the hearts and hopes of America. Tom signed a book deal. He showed up on the stage for the Kraft Music Hall, a popular TV show, singing "Nancy (With the Laughing Face)" to his wife, accompanied by The Lettermen.

Tom and six of his teammates were booked for 17 days at Caesars Palace for $10,000 each to appear in singer Jimmie Rodgers's show. The boys sang "The Impossible Dream." Seaver left the gig early. He and Nancy decamped to the Virgin Islands.

A winter stock theater in Florida offered him $10,000 a week for a seven-week run. He turned it down.

One day, in November, while planning to winter in the New York area, he went shopping for a coat. Reporters were there. He decided on a size 43 long double-breasted mountain lion coat, but only after asking if there were any conservation laws against it. The proprietor produced a certificate that the lion was shot legally in the mountains of Mexico. Nancy picked out a coat for herself ($3,000 amber fox).

Fame is like wine: both sweet and dangerous, depending on how you consume it. Seaver sipped appropriately. On Dec. 15 he showed up at Toots Shor's for the premiere of the official World Series film. He revealed that he and Nancy had just bought an old farmhouse in Connecticut.

"You begin to value privacy much more," he said. "You don't have a moment to yourself or a moment to share with your teammates."

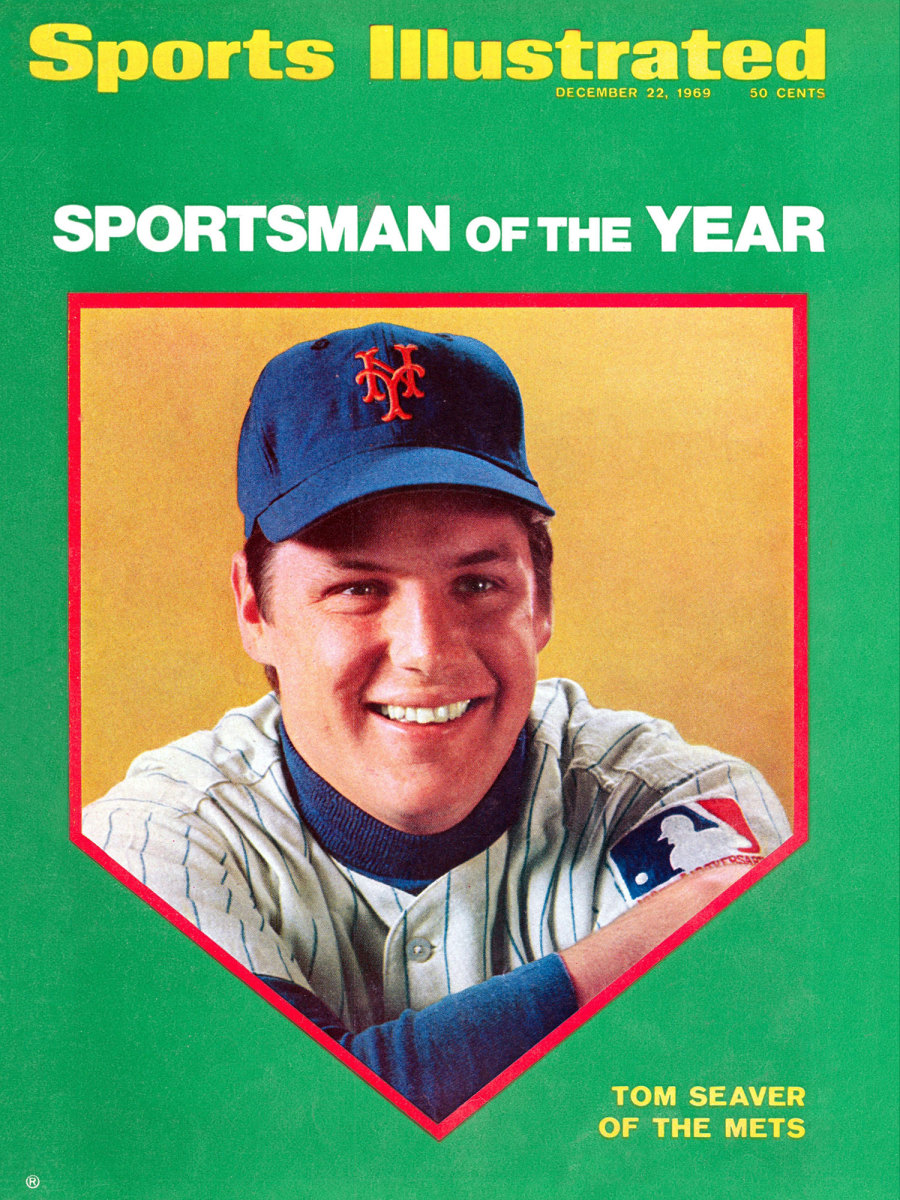

Two days later Seaver received the SI Sportsman of the Year award.

Officially handed the Grecian urn that goes with the award, Seaver spoke eloquently for 10 minutes. In conclusion, he turned to Nancy and said, "I couldn't have done it without her."

Nancy ("gray cashmere pants suit") broke down in tears.

"I told you not to cry," Tom said.

***

I was the immature one then. I was content just to be the lady of the moment, to get a taste of all those things that two kids from Fresno never get. I never stopped to ask him about goals. But Tom always has known what he wanted and where he was going.

—Nancy Seaver in 1981

Beauty is as ephemeral as the dried seeds of dandelions floating on a summer breeze like wispy, white parachutes. The sun over Napa Valley can only last for so long. It fell lower in the sky, lengthening the shadows of the grape arbors on Diamond Mountain. It was time to go. Time to say goodbye. Nobody wanted to say it, but they knew it was probably the last goodbye.

"It was eight to nine hours of unbelievable memories," Shamsky says. "When we left, it was bittersweet. Saying goodbye to guys in their 70s, you don't know what's going to happen."

Heeding a call within the soul, man must create. Only the most fortunate create as fully as did Tom Seaver. He created art—yes, art, because he made art on the mound—a loving marriage now in its 54th year, two daughters, a Hall of Fame career, a model of comportment, the winery, countless friends, goodwill and an aesthetic of time and place from 1969 that never will be duplicated or forgotten. But amid earth, air, sun and sky and the very fruits of their yield, even the most accomplished man is humbled by what is created from above.

Surrounded by his teammates in the vineyard, Seaver surveyed the greatness of this creation spread before him and told them, "You know, if I couldn't do anything else but walk out here every day with the dogs, I'd be happy."

Seaver is one of between five and six million Americans suffering from dementia. A 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 8.8% of the population 65 and older has dementia, a rate that works out to an average of about two or three players from a world championship team of 50 years ago. Working on his own book, Swoboda telephoned Seaver one day. It was around the time the teammates visited Tom on Diamond Mountain. Swoboda wasn't sure if it was just before or just after the get-together.

"Remember when Hodges came out to visit you on the mound in the ninth inning in the World Series?" Swoboda said to Seaver. "What did he say to you?"

Seaver could not remember the meeting.

"Remember that almost perfect game you had against the Cubs?" Swoboda asked.

Again, Seaver had no memory of it.

"Tom just didn't remember," Swoboda said. "He couldn't put any of those little pieces together. He couldn't find them. They were gone.

"It rattled me, if only because those memories are such treasures to me. The thought that something could sneak in and steal them from him and that now they are gone, just gone, is tragic beyond words."

Dementia is our most expensive disease. The cost of care is greater for dementia than for heart disease or cancer. The toll on loved ones when the mind fails before the body is incalculable.

Once in the flower of his youth, on the cusp of making it big, Seaver experienced a pitching epiphany. He was 22 years old and pitching a spring training game against the Braves, part of his first major league camp after a 12-12 season at Jacksonville the previous season.

"I gave up a couple of hits and fanned three or four men," he once remembered. "I suddenly saw if I pitched up to my capacity and used my head as well as my arm, I could get major league hitters out."

The head and the arm, in equal brilliance, served Seaver as well as any pitcher who climbed that dirt hill to answer the challenge, which makes his declining cognition all the more heartbreaking. Shakespeare's aging, dementia-stricken King Lear, in as anguished a tragedy as has ever been written, asks poignantly, "Who is it that can tell me who I am?"

He is Tom Seaver, the archetype of the thinking man's pitcher. Fifty years ago, Seaver and the 1969 Mets defined what was possible. Not just for a year, but for an eternity, even as the memories of such wonder are being stolen from his own beautiful mind.