Nationals' Dream Season Nothing Short of a Miracle

HOUSTON – One hundred five years ago, a team won the World Series so improbably that to this day it occupies a sacred place among the 115 champions. The 1914 Boston Braves are forever the Miracle Braves. They came from so far down—16 games below .500—that they are baseball’s patron saints of lost causes.

Older than the toaster, the Miracle Braves have remained alive as the epitome of long shot champions. We conjure them like incense or prayer. It took more than a century, but now they have company.

The 2019 Washington Nationals are world champions that never shall be forgotten, as much for how they did it as who they are. They came from 12 games down (19-31) to win the World Series, a resuscitation bettered only by the Miracle Braves.

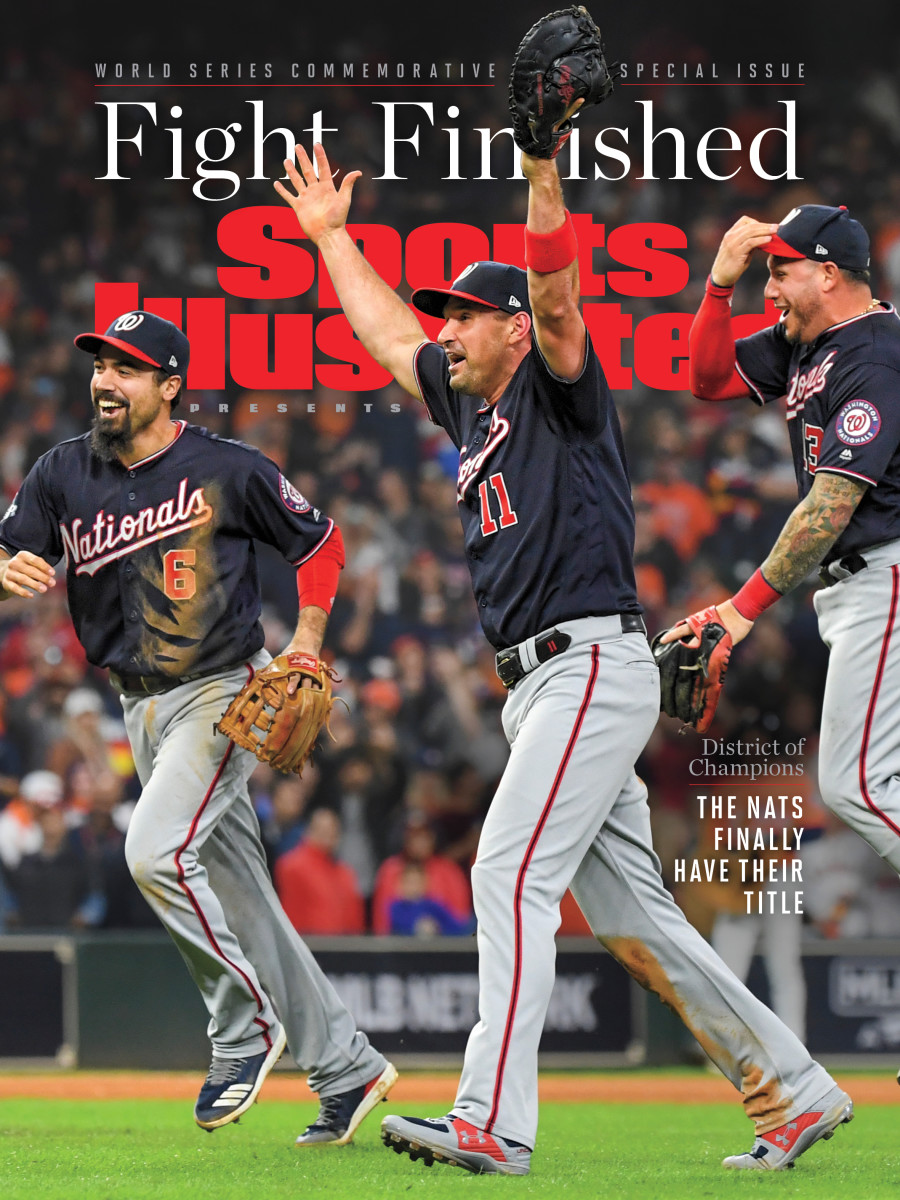

• Get SI’s Washington Nationals World Series Champions commemorative issue here.

But their ascension is so much more than that. Five times they played a postseason game in which a loss would have ended their season. In each of those elimination games they fell behind. The pitchers they faced in those near-death deficit situations were Josh Hader, the National League relief pitcher of the year; Rich Hill, the lefthanded curveball specialist; and three Cy Young Award winners, Clayton Kershaw, Justin Verlander and Zack Greinke.

The Nationals won all five games by a combined score of 30-11, including 19-0 from the seventh inning on. They became the first team to mount five come-from-behind wins when facing elimination, including a 6-2 comeback to win World Series Game 7 against the Houston Astros. If this season wasn’t another miracle, it at least bordered on the supernatural.

“I do think this was a destined team,” says Washington hitting coach Kevin Long. “What this team has done will go down as one of the most amazing feats any team will ever accomplish.”

At so many turns the Nationals defied the logic of natural baseball law, such as the idea that a ridiculous, stick-to-your-brain toddlers’ tune could become the equivalent of a fight song for a fan base. (“Baby Shark” was their “Hell’s Bells” or “Dirty Water”.) Or that you could even make the playoffs with a bullpen ERA as bad as 5.68, which no team had ever done before.

The manager actually had to watch a World Series game with a cardiologist standing by him. One of the ace pitchers, with his neck and arms locked in spasms, literally fell out of bed on the day he was supposed to start Game 5. The other ace won the World Series MVP, but only because a video coordinator alerted the pitching coach that he was tipping his pitches. The man who closed the series was released by the pitching-poor Angels in spring training. The team suffered the worst three-game home sweep in the history of the World Series.

Somehow it all ended with the first World Series title in Washington since 1924, which was so long ago that Walter Johnson was the winning pitcher of the final game. The span of 62 baseball seasons without a title since then—major league baseball went dark in D.C. for 33 years between the Senators leaving and the Nationals arriving—was the longest running streak except for the 71-year drought Clevelanders have been enduring.

In just the past 15 years baseball has wiped out half of the dozen longest World Series droughts: the 2016 Cubs (107 years without a title), 2005 White Sox (87), 2004 Red Sox (85), 2017 Astros (55), 2010 Giants (55) and 2019 Expos/Nationals (50).

“This year,” Washington manager Dave Martinez says, “I can honestly say nothing would have surprised me. We’ve been through a lot.

“But like I said before, these guys, we stuck together. They believed in each other. I believed in them.”

Martinez is the votive candle on which the Nationals placed their prayers—or at least the Autumn Wreath aromatherapy candle he burned in his office before every World Series game, home and road. Martinez also plays soothing music out of a boombox that emits mood-friendly lights, sips tea, and speaks in the quiet, optimistic ways of a yogi. Such placidity came in handy when the Nationals lost 31 of their first 50 games, when the pitching coach, Derek Lilliquist, was fired and Martinez and anyone else on the staff knew they could have been next with one more bad week.

“They could have fired us all,” Long says. “We were all in jeopardy of being fired. [Lilliquist’s firing] was very emotional. When he left he said, ‘I know you guys will figure it out.’”

As they began to get injured players back, such as shortstop Trea Turner and third baseman Anthony Rendon, the Nationals held a team meeting and vowed to stay the course.

“I’ll never forget it,” Long says. “It was around that time we were 19-31. We were all in the conference room at home. We just came together and decided, ‘We’re going to be all right.’”

• Nationals fans, get your World Series championship gear here.

Martinez always had a calmness about him, even when he was 13 years old and came home from school one day to be told by his parents that they were shipping him from New York to Florida to live with an uncle. His mother and father saw great baseball talent, and wanted it nurtured on groomed playing fields of Florida rather than the concrete and asphalt of upper Manhattan.

Martinez did grow that talent into a 16-year major league career. Five years after retirement, Martinez joined manager Joe Maddon as a guest instructor at the Tampa Bay Rays’ spring training camp. Rays general manager Andrew Friedman was so impressed by how Martinez quickly connected with everyone there—young, old; English-or Spanish-speaking—that he eventually added Martinez to the staff. Maddon brought Martinez to the Cubs in 2015 as his bench coach, and Nationals GM Mike Rizzo hired him for the 2018 season to be Washington’s manager.

Truth be told, these days Martinez’s cool mannerisms also happen to fall under doctor’s orders. Martinez, 55, felt such severe heart pain and dizziness on Sept. 15 that he briefly was hospitalized. He underwent a catheterization. His cardiologists ordered him to cut out caffeine (which meant goodbye to his half-dozen cups of coffee a day) and his post-game glasses of wine, and to sit rather than stand during games.

“My doctors keep wanting me to take a stress test,” Martinez says. “I tell them, ‘Are you kidding me? I’m getting one every night.’”

Watching the Nationals play in the postseason tested any ticker. They made a habit of getting to the brink of expiration, only to rally. No greater stress test developed for Martinez than the fire drill of a seventh inning that happened in Game 6. Washington had been down 2-1 to Verlander but rallied for a 3-2 lead on homers by Adam Eaton and Juan Soto. The seventh looked like a tack-on rally when pitcher Brad Peacock threw wildly to first on a topped grounder by Turner. As first baseman Yuli Gurriel reached for the throw, Turner, who had been running outside the 45-foot running lane, collided with Gurriel’s mitt on his last stride to the bag.

Home plate umpire Sam Holbrook called Turner out for interference. The controversial call became moot when Rendon smashed a two-run homer off Houston reliever Will Harris. Still, Martinez took up his argument with Holbrook after the inning, and did so with such vehemence he had to be restrained by bench coach Chip Hale from getting to Holbrook. Martinez was ejected, whereupon he retreated to his office at Minute Maid Park.

During the 7th inning stretch, Nationals Manager Dave Martinez was visibly upset with the umpires and was ejected during the exchange. pic.twitter.com/AZ23MusrNN

— FOX Sports: MLB (@MLBONFOX) October 30, 2019

A cardiologist immediately checked on Martinez, who was found to be suffering from a brief bout of shortness of breath. The doctor remained with Martinez as the Nationals closed out what was a 7-2 win.

The winning pitcher, for a second time in the series and a record-tying fifth time in the postseason, was Stephen Strasburg. He recovered from yielding two first inning runs only after Jonathan Tosches, the team’s 37-year-old coordinator of advance scouting, who is assigned to the team’s replay review monitor, noticed that Strasburg was tipping his pitches with the position of his hand and wrist as he gripped the ball in the set position. Tosches remembered how Strasburg had the same problem Aug. 3, when the Diamondbacks hung nine runs on him.

Tosches told pitching coach Paul Menhart, who told Strasburg after the second inning. The pitcher then began flapping his glove as he came set, which covered any pitch-tipping. The Astros didn’t score another run off him, going quietly at 3-for-21 as if they didn’t know what hit them.

“He told me it was—what is the right word here?—just so reassuring to him,” Menhart said about Strasburg. “It gave him such relief and confidence. He said, ‘I got takes on balls they were hitting before, and they were swinging and missing at balls they were spitting on in the first inning.’ It freed him up.”

Strasburg’s win brought the series back into the hands of Max Scherzer, which seemed an impossibility three days earlier.

Scherzer had been scheduled to pitch Game 5, but awoke that morning with his neck and upper shoulder so locked up with spasms that “it was impossible to pitch.” He was so rigid that his wife, Erica, had to dress him.

“The worst was when I woke up and couldn’t move,” Scherzer says. “I couldn’t even lift my arm above my shoulder. I was devastated because I knew I was letting the team down. The only way I got through that was my wife. She kept telling me, ‘Don’t worry. It’s going to be all right. Stras is going to deal and then you’re going to pitch Game 7.’ I’m telling you, there’s no way I get through that without her.”

Said Martinez, “When I saw him Sunday, I thought there’s no way he’s pitching again in the series.”

Said Long, “I saw him in the training room and thought he just had surgery or something. Seriously, he looked terrible. I didn’t know what happened.”

Doctors administered a cortisone shot to relax the muscles in his neck, after which they told Scherzer to do absolutely nothing for 24 hours.

“Do you know how hard that is for Max?” Martinez says. “He was told, ‘Don’t pick up anything. Don’t do anything with your arms.’ But he was good with it.”

He slept with a brace around his neck. Twenty-four hours after the shot, chiropractors worked on the area twice a day, hours at a time. He played catch before Game 6 and felt better.

• Get SI’s Washington Nationals World Series Champions commemorative issue here.

The next morning, soon after he awoke, Scherzer sent Martinez a text.

I’m good, it said.

“I got that text from him in the morning and knew he was good,” Martinez said about the morning of Game 7. “Then I saw him on the bus to the ballpark and he had his Max Scherzer game face on. That’s when I really knew he was good.”

Martinez gathered his team briefly before Game 7. Throughout the stretch run and the postseason, Martinez had emphasized to his team the importance of “staying in the moment”—not thinking about how many wins they needed but only the next one. His slogan became, “Let’s go 1-0 today.”

“Hey, I want you guys to just treat this as just another game,” Martinez told them. “It's Game 184, which is hard to do. But we made it this far. Just play one more game. One more 1-0.”

For six innings, the Nationals could do next to nothing against Greinke, who was throwing a one-hit shutout and making a 2-0 lead hold up. Houston ace Gerrit Cole was looming in the bullpen behind Greinke, the choice of Astros manager AJ Hinch to start an inning with a chance to win the World Series.

“When Cole was warming up we were like, ‘Please, bring him in. Anybody but Greinke,’” Long says. “That’s how good Greinke was. I’ve seen Greinke a lot and I’ve seen Greinke good. This was the best I’ve ever seen him.”

Scherzer pitched gallantly. Houston did nick him for two runs, the first when Yuli Gurriel became the first man to homer off Scherzer’s slider since Aug. 8, 2018—an incredible run of 766 consecutive sliders Scherzer kept in the yard. But Scherzer, dodging in and out of traffic, ended his five innings by stranding nine runners.

Trailing 2-0, the Nationals were down to their last eight outs when Greinke hung a 1-0 changeup to Rendon, one of the rare times Greinke left anything over the plate. Rendon crushed it into the Crawford Boxes in left. Washington still trailed, 2-1, but the tenor of the game had changed as surely as a window had been broken. Now the Nationals had Houston on the run.

Rendon with a ROCKET. #WorldSeries pic.twitter.com/KJKPAdx8ud

— MLB (@MLB) October 31, 2019

“That’s the at-bat that got us going,” Long says. “Anthony Rendon is the best hitter in baseball. Why? Because he does whatever is needed to be done. Give me any hitter against any pitcher in any situation and I’ll take Tony every time. That’s why I say he’s the best hitter in baseball.

“And when he got back to the bench he says real calmly, ‘Howie [Kendrick] doesn’t have a hit yet. It’s going to be his turn.’”

Next up was Juan Soto. It seemed Rendon and Soto were always batting out of order, such was the disruption they caused opponents. Every rally seemed to work its way through those two spots in the lineup.

Rendon’s homer changed how Greinke would have to pitch Soto. With a two-run lead, Greinke could have attacked Soto. But now that Soto represented the tying run, Greinke had to pitch him with the express purpose of keeping him in the ballpark—no easy task with the way Soto was running through All-Star pitchers in the postseason.

So confident is Long in Soto that before Game 1 he predicted, “I guarantee you he’s going to hit a home run off a high fastball” from Cole. His second time up, Soto did exactly that, whistling a high fastball onto the train tracks high above the leftfield wall—the longest opposite-field homer by a lefthanded hitter at Minute Maid Park in at least the past five years.

Cole decided to try another high fastball against Soto in Game 5, and Soto smashed that one to dead center for another homer. The next game Soto blasted a majestic homer off a high fastball from Verlander. That gave Soto five postseason homers, all off 2019 All-Star pitchers: Hyun-Jin Ryu, Kershaw, Cole (twice) and Verlander.

So Greinke approached Soto with extreme caution. He did get one swinging strike on a big curveball, but otherwise Greinke threw him four pitches far off the outside of the plate. He succeeded in not allowing a homer, but with the walk Greinke brought the go-ahead run to the plate and prompted Hinch to remove him from the game. That walk was the Jenga piece to Game 7.

The Game 1 swing Soto put on Cole haunted the Astros for the rest of the series. Oddly, their scouting report said they could get Soto out with high fastballs, even though Soto slugged .873 on high fastballs, the fifth-best mark in the regular season. Still they kept trying and still they kept getting burned.

They were burned when they pitched to Soto, and burned when they didn’t. They walked him five times, including the only intentional walk Hinch ordered all year. Four of those walks led directly to runs.

“That’s why Juan Soto is so special,” Long says. “He goes and takes his 90 feet. It’s amazing. He’s 21 years old. What do most 21-year-olds want to be? They want to be the hero. He’ll take his walks. He’s a hero for taking his walk.”

Said Martinez after the game, “You look at Rendon, who has no heartbeat. He’s just the same guy every day, every play, every second. And then you look at Soto, who’s a 20-year-old—well, a 21-year-old now, he had his first beer tonight, which is kind of nice— but you look at a 21-year-old kid that's just out there having fun like he's playing stickball in the backyard. That's who he is. He loves the moments. He loves going up there and picking up his teammates.”

The walk pushed Hinch up against his decision tree. Still up 2-1, Hinch still could win the World Series by covering eight outs. He had two choices to get them: use Harris and Roberto Osuna, or, as he suggested before the game, use Osuna and Cole for those outs. (Cole was not going to be thrust into a game mid-inning, but he could close the ninth if Osuna picked up five outs.) Hinch opted for Harris and Osuna.

“I wanted the game in the hands of my two best relievers,” said Hinch, who was leery about pushing Cole on two days of rest and with a huge free agent payday on the other side of the World Series.

There was one risk in his choice: Harris was on fumes. This was his 12th postseason appearance, including his fourth in five games. He had made a mistake with a 1-0 cutter to Rendon the previous night and paid for it with a homer. Now he was tasked with getting Howie Kendrick. This time it was an 0-1 cutter—not a terrible pitch, but a pitch in the strike zone away—that Kendrick caught flush, sending the baseball toward the rightfield corner. It clanked off the screen attached to the foul pole.

HOWIE FEELING, NATS FANS?! pic.twitter.com/TTO7sHHd5j

— MLB (@MLB) October 31, 2019

Just like that, in a span of nine pitches to three batters, the Nationals went from getting shut out to a 3-2 lead, a lead that was in the trusty hands of lefty Patrick Corbin.

Washington tacked on a run in the eighth when Hinch, caught in the Soto trap again, elected this time to pitch to Soto with first base open. Soto ripped a run-scoring single. Two more runs came across in the ninth on a single by Eaton.

Martinez called on Daniel Hudson to pitch the ninth. The series had been a strange one, especially because the road team happened to win all seven games—the first time the road team won as many as six games in any best-of-seven MLB, NBA or NHL series. The oddity was due mostly to Scherzer and Strasburg starting all four road games for Washington in the series. Across the postseason the Nationals went 10-0 when Scherzer and Strasburg started and 2-5 when they tried anybody else.

• Nationals fans, get your World Series championship gear here.

Moreover, the actual ballgames were so pedestrian as to fade into the background of what otherwise should have been the marginalia of the series: Scherzer’s neck, two flashers’ breasts, the belly of a two-fisted beer drinker that absorbed a hard-hit homer, the $12 million worth of bets lost by a Houston mattress magnate, the tweets of umpire Rob Drake, the actions of Astros executive Brandon Taubman, and the well-rested right arm of President Donald Trump, who showed up at Game 5 at Nationals Park but continued to be the only president not to throw out a first pitch since William Howard Taft started the presidential tradition in 1910.

Not only did the Nationals not win a game at home, but they also were outscored 19-3 without holding so much as a lead.

They saved their best work for the road. Their first comeback elimination win happened at home, when Soto beat Hader with a single that took a strange sideways bounce past Milwaukee rookie rightfielder Trent Grisham. After 50 years of Montreal Expos/Washington Nationals baseball without a pennant, and a franchise record of 1-5 in postseason series, that odd bounce of the baseball was the first clue that this year would be different, if not miraculous.

Then they took out the Dodgers with comeback elimination wins in NLDS Games 4 (at home) and 5 (at Dodger Stadium), before rallying at Minute Maid Park in World Series Games 6 and 7 against Verlander and Greinke, who rank 1-2 in career wins among active pitchers.

“When I took the mound,” Hudson said about the ninth inning of Game 7, “I told myself not to try to throw hard. Because I knew it was going to be there no matter what.”

Hudson was the last Washington pitcher of the World Series clincher, just as Johnson was in 1924 when the Senators beat the New York Giants on a 12th-inning walk-off double by Earl McNeely. Johnson was born in 1887. Hudson was born 100 years later. Hudson struck out Michael Brantley, swung a fist through the air, then flung his glove in the direction of his team’s dugout.

Among the first to greet him was Corbin, the winning pitcher in the clincher. Only three men ever won a World Series Game 7 with three or more innings of shutout relief. Corbin and Johnson are two of them (Joe Page of the 1947 Yankees is the other).

For the first time in 95 years, Washington is first in war, first in peace and first in major league baseball. But in their own way, these Nationals stand apart from their Senators forefathers and all the other 113 champions. Nobody else won the World Series like this—coming back from 12 games under and then coming back to win five elimination games. Next year, next decade, and even 105 years from now, the resolve of the 2019 Nationals will be as indelible as the miracle that was the 1914 Braves.