Why MLB Issued Historic Punishment to Astros for Sign Stealing

The largest sign-stealing scandal in the history of baseball, a game that for more than a century treated the dark arts of cheating with a wink and nod, began with Major League Baseball embracing technology.

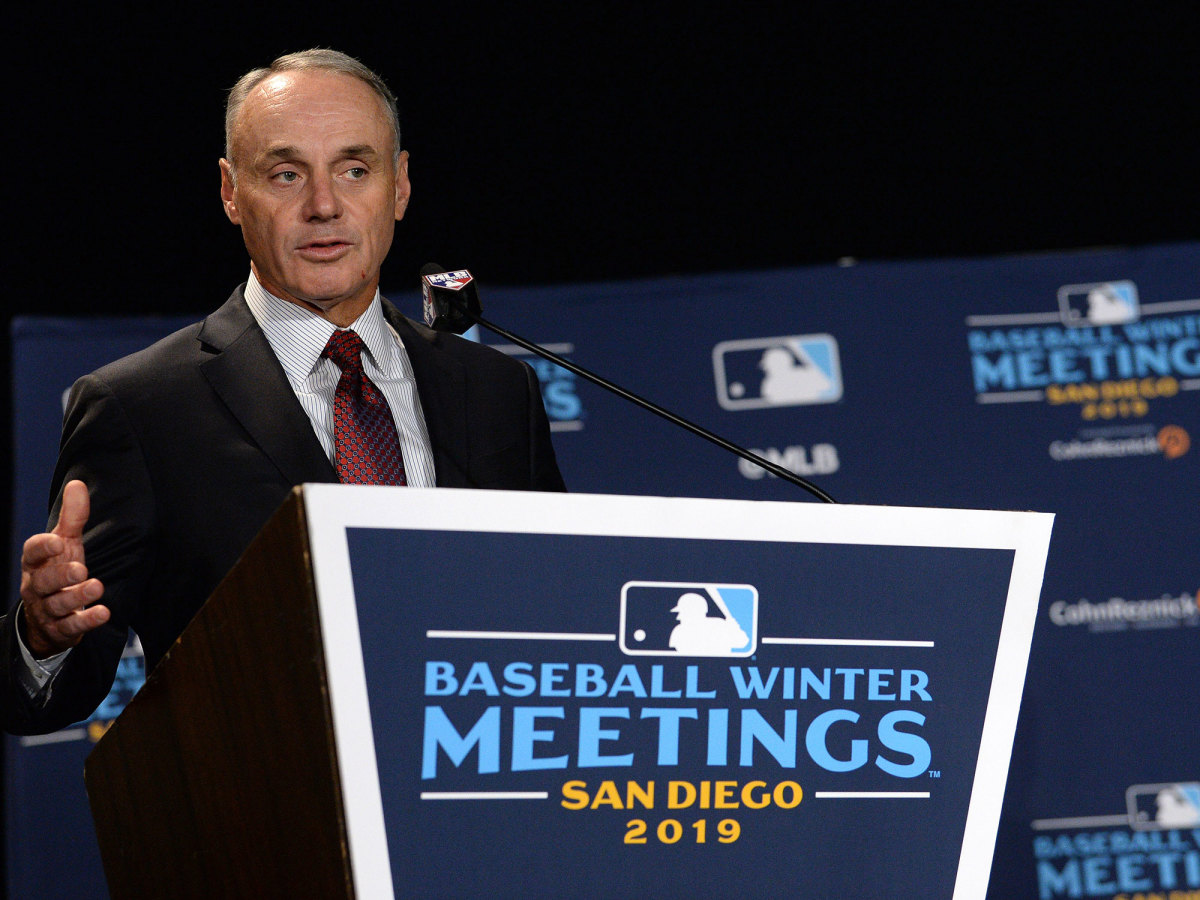

In 2014 MLB adopted a challenge-based replay system that put live television monitors close to dugouts. If Pandora’s Box unintentionally opened then, commissioner Rob Manfred, in the most severe action of his five-year term, attempted to slam it shut Monday by imposing massive precedent-setting penalties against the Houston Astros for their misuse of technology in 2017 and 2018.

MLB suspended Astros manager AJ Hinch and general manager Jeff Luhnow for a year, through the 2020 World Series. (Editor's note: Astros owner Jim Crane has since fired Hinch and Luhnow.) The team has been stripped of its first- and second-round draft picks in 2020 and 2021. Additionally the league fined the Astros $5 million, the maximum amount allowed under the MLB Constitution. No players were suspended as the league chose only to go after the club's managerial figures.

Perhaps the most damaging information to come from Major League Baseball's report is that its investigation found the Astros used their replay room and video monitor improperly “throughout the postseason" in 2017, when Houston won the World Series. The report officially taints Astros' title.

In the kind of informational archeology reminiscent of The Steroid Era, baseball is learning what happens when “gaining an edge” pushes into new frontiers. Two sources familiar with the investigation, which lasted three months and included more than 70,000 e-mails and 60 interviews, said various Astros personnel told MLB investigators about eight other teams who used technology to steal signs in 2017 or 2018–such was the culture of the time.

Only one of those teams, the Boston Red Sox, is under a known investigation as a result of information baseball found credible. Boston now understands the scope of possible penalties, including to Alex Cora, its manager. Cora is linked to both teams, as bench coach for the 2017 Astros and manager of the 2018 Red Sox. Both teams won the World Series. According to MLB's report, Cora used the Astros dugout phone connected to the replay room to obtain information on opponents' signs early in the 2017 season.

When Manfred researched precedents for sign-stealing penalties he found them “woefully inadequate” where they existed at all. Moreover, he knew the reach and ease of use of technology created temptations like never before. With these penalties he defined the penal system for the electronic age: violators risk their place in the game, and it is management, not players, who bear the greatest responsibility.

Manfred sat down with SI last week for a wide-ranging interview on the occasion of the upcoming fifth-year anniversary of his commissionership. He was hired January 25, 2015 to a five-year term. Owners granted his second term, also five years, as part of an extension in November 2018. (The fuller scope of that interview will run in the next issue of the magazine.)

During that interview Manfred told SI that holding officials, managers and coaches more accountable than players is “bigger here than union protection. It’s about recognizing the reality that figuring out which individual players were in and out and what their participation was, you just never are going to get there in the clubhouse culture that exists.

“It’s a question of putting the responsibility on people who have an opportunity to really make a difference as to whether the activity goes on in the first place.”

Manfred hit Hinch with the second-longest suspension of a manager in baseball history. Only Pete Rose, banned in 1989 for life for gambling received a longer punishment.

MLB found that while Hinch did not participate in or condone the infractions, it disciplined him for failing to stop them in a timely manner. The Astros stole signs for three months in the 2017 regular season before Hinch at least twice explicitly made known to the players he disapproved of the behavior by breaking the television monitor.

Paranoia about sign-stealing and the misuse of technology has grown so wild that some news reports suggested the Astros may have relayed signs with the use of a buzzer embedded in bandages on the skin. (Such an idea led to speculation that Houston catcher Robinson Chirinos scrambled to recover such an electronic bandage that fell while batting in the 2019 World Series. Actually, it was a pad to protect a bone bruise in his hand).

“I will tell you this: we found no Band-Aid buzzer issues,” Manfred told SI. “There’s a lot of paranoia out there.”

This is the story of the digital age. This is the story of how the temptation of technology ensnared baseball, why Manfred dropped such a heavy hammer, and where baseball goes from here.

The Beginning

On January 16, 2014 MLB announced the approval of an expanded, challenge-based replay system. Embedded in that announcement was a section titled “Club Access to Video.” That section established that “personnel in the dugout will be permitted to communicate with a video specialist in the clubhouse who has access to the same video that is available to replay officials.”

The unintended consequence of getting calls right on the field gave players easy access to real-time video. Many replay monitors, on the premise of expediency, soon moved from the clubhouse to positions closer to the dugout, as the Astros did at Minute Maid Park.

By 2017, teams had figured out that access to live video provided a competitive advantage. In June of that year, Carlos Beltran, culling from knowledge gained from a previous year, decided to use the replay monitor in home games to figure out what pitch was coming. Support personnel could watch video–which included a dedicated camera on the home plate area–to decode the catcher’s signs.

From there, according to a source familiar with the investigation, a system developed. “It kind of grows,” the source said. “It wasn’t like a massive program that started one day. It happened over time.”

It worked like this: when the catcher called for an off-speed pitch, support personnel would bang a hard plastic trash can, which was stationed next to the monitor just steps from the home dugout at Minute Maid Park. The batter would be able to hear the bang to know an off-speed pitch was coming. If he heard nothing, he sat on a fastball.

ICYMI - This is the infamous garbage can banging noise from a Blue Jays and Astros game back in 2017. It's very clear if you listen with headphones, too. pic.twitter.com/FLevUbzKnj

— Ian Hunter (@BlueJayHunter) November 14, 2019

Not all Astros used the system and those who did used it part of the time. Houston’s hitting against non-fastballs at home in 2017 improved only marginally in the second half as compared to the first (from .249 to .252 in batting average and from .396 to .415 in slugging).

But knowing what was coming allowed the Astros not to chase as many breaking pitches and changeups–pitches designed to work on deception. The Astros lowered their chase rate on non-fastballs at home from 30.2% in the first half to 26.9% in the second half.

The Astros were not alone in corrupt use of technology at the time. Just two months after the Astros’ system began in 2017, Boston took two out of three games from the Yankees in a series at Fenway Park August 18-20. The Red Sox hit .333 with runners in scoring position in that series, including .375 with a runner on second base, whence he could signal pitches to the batter. (The Red Sox would finish two games ahead of the Yankees to win the AL East.) After that series New York general manager Brian Cashman filed a complaint with the commissioner’s office that Boston was stealing signs.

An investigation by the commissioner’s office confirmed the Red Sox for several weeks had been using the replay monitor to steal signs. Their system support personnel watching the replay monitor communicated via Apple Watch with a trainer in the dugout about the next pitch. The trainer would alert a player standing nearby. The player would communicate to players on the field, such as the runner at second base, through hand signals. The runner at second could inform the batter.

Manfred fined the Red Sox. (Boston filed a counter-claim against New York. The commissioner’s office issued a smaller fine to the Yankees for improper use of a dugout telephone in a previous season–related to communication between coaches and the replay monitor about whether pitches were balls or strikes.)

Upon first learning of the Red Sox’s espionage, Manfred said, “We’re 100% comfortable that it is not an ongoing issue.”

In fact, Manfred quickly learned the game was awash in electronic sign stealing and the paranoia it engendered. The Boston scandal was a turning point for him. It opened his eyes to the unintended consequences wrought by the replay system.

The Warnings

Baseball has a long history of stealing signs from outside the playing field. In 1973, for instance, Rangers manager Whitey Herzog filed a complaint that Bernie Brewer, the Milwaukee Brewers mascot clad in Bavarian clothing, relayed signs to Milwaukee hitters by clapping with his white gloves or not while sitting in the outfield bleachers at County Stadium.

As Manfred was deciding what to do about sign stealing in 2017, he researched how baseball treated such past incidents. The answer: with little more than a wink and a nod.

“One of the reasons we did what we did in September ’17 was there were some sign stealing penalties going back years and years and the precedent was woefully inadequate to address today’s environment,” Manfred said. “I felt it was necessary to put people on notice that it was going to be a different penalty structure if people continued to disobey.”

The National League in the early 1960s, for instance, endured rampant accusations of illicit sign stealing. The Braves in 1960 stationed two starting pitchers in the centerfield bleachers of Wrigley Field, where they could signal the signs of the Cubs’ catchers with white scorecards. In a turnabout in September 1961, Braves manager Birdie Tebbetts filed a protest that the Cubs used lights in the scoreboard to signal pitches: a steady red light for a fastball and a blinking one for an off-speed pitch.

No penalties were issued. Responding to the accusations, National League president Warren Giles simply warned teams that stealing signs from “a vantage point not available to both teams was unsportsmanlike and a violation of the rules.” The potential penalty? Merely that the game might be replayed if the winning team were the offender. (Such penalty never occurred.)

The most recent action by the commissioner regarding the use of electronics involved the Yankees during the 1976 World Series. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn fined New York Yankees manager Billy Martin $1,000 for “conduct not in the best interest of baseball.” In the 1976 postseason the Yankees used Clyde King as their “eye on the sky” to position their defenders. King communicated with coach Gene Michael via walkie-talkies. The commissioner’s office pre-approved the system, but the Reds protested when King and two other New York scouts watched the World Series in Cincinnati from a radio booth equipped with a television monitor, not from the stands as they had done in the ALCS against Kansas City. Cincinnati charged King could steal signs with the use of the monitor. Martin’s fine was related to public comments about the Reds’ complaint, not to any actual sign stealing.

Manfred knew the game had entered a new era with the explosion of technology. On Sept. 15, 2017, in his statement announcing his fines of the Red Sox and Yankees, Manfred admitted “the prevalence of technology, especially the technology used in the replay process, has made it increasingly difficult to monitor appropriate and inappropriate uses of electronic equipment.”

He drew a line in the sand: “All 30 clubs have been notified that future violations of this type will be subject to more serious sanctions, including the possible loss of draft picks.”

Manfred explained, “When I did the fines with the Yankees and the Red Sox it was wholly out of whack with fines of the past and I knew it was thin soup at the time, which is why I wrote the thing the way that I did. Just stop. You have to stop. I think you know how clubs are about [draft] picks. That’s why I explicitly mentioned draft picks.”

Just six days after Manfred dropped his warning, the Astros used their trash can system against the Chicago White Sox, according to video and audio from the game. The moment Houston violated the commissioner’s Sept. 15 warning is the moment the Astros became subject to severe penalties.

According to two sources familiar with the investigation, Houston did not use the trash can system in the 2017 postseason. Banging on trash cans would be too obvious in the heightened scrutiny of the postseason environment.

Instead, playoff teams in 2017 would have to be more discreet about using technology to steal signs. Paranoia ran deep. By the end of the World Series, which had the sub-context of a sign-stealing competition between the Dodgers and Astros, Manfred knew the Boston scandal was only the tip to a massive iceberg.

According to one baseball source, MLB “spent the entire ’17 postseason running back and forth chasing down allegations about who was stealing signs. Everybody was charging everybody with doing it.”

Manfred doubled down on his warning. On March 27, 2018, under the signature of chief baseball operations officer Joe Torre, Manfred sent a three-page memo to “all club presidents, general managers and assistant general managers” defining the limits of technology. His goal was to remove any ambiguity that may have existed from his Sept. 15 statement.

The 2018 memo stated, “Electronic equipment, including game feeds in the club replay room and/or video room, may never be used during a game for the purpose of stealing the opposing team’s signs.”

In boldface the memo emphasized, “To be clear, the use of any equipment in the clubhouse or in the club’s replay or video rooms to decode opposing signs during the game violates this regulation.”

Said Manfred, “The way I read what I wrote was that there was going to be club responsibility and the people most able to control what was going on were field managers and general managers and it was their responsibility to make sure things were done correctly. Management has certain rights. They also have certain responsibilities.

“We made a decision in the 2017-18 offseason to draw the line.”

Still, the paranoia about cheating continued. Baseball announced that before the 2018 postseason “a number of clubs called the commissioner’s office about sign stealing and the inappropriate use of video equipment.” The charges came against “a number of clubs.” In February 2019 Manfred responded with stronger protocols against the misuse of technology, including banning all non-network cameras from foul pole to foul pole and placing all clubhouse and bullpen monitors on an eight-second delay.

The Investigation

Mike Fiers led the 2017 Astros in innings pitched but after he slumped down the stretch the Astros left him off their postseason roster. Last November he told The Athletic about his team’s sign-stealing stealing system, adding that he had warned his subsequent clubs, the Tigers and Athletics, about the need to be vigilant about signs when they play in Houston. The commissioner’s office promptly launched an investigation.

“The investigation was thorough and extraordinarily well done and provides a sound factual basis for us to make disciplinary determinations,” Manfred said.

Astros employees were forced to turn over their e-mails and cellphones. Investigators grilled them about the meaning behind some seemingly innocuous text messages.

At the time baseball already had launched an investigation into Houston assistant general manager Brandon Taubman for his profane outburst toward female reporters after the clinching game of the 2019 ALCS, and the tone-deaf manner in which the team initially came to his defense. In MLB's report, Manfred said Taubman has been placed on the league's ineligible list.

Baseball also had investigated an incident at Yankee Stadium in May 2018 in which Taubman and another Houston front office employee, Kyle McLaughlin, walked to a centerfield camera well to confront a Yankees employee operating a camera. It turned out the Yankees had approval to use what was a slow-motion camera for pitcher training purposes.

In the 2018 postseason the Astros stationed an employee in camera wells near the home dugouts at Progressive Field in Cleveland and Fenway Park in Boston to surveil opponents with a cellphone camera. The Astros claimed they were “playing defense” against the possibility their opponents were cheating.

Leading into the 2017 postseason an Astros official suggested to advance scouts they surveil opposing dugouts to decipher signs.

Evidence kept mounting against questionable institutional control in Houston, though no penalties were assessed. But as baseball investigators dug into the trash-can system allegation, they found a new violation from 2018. Even after the explicit March 2018 warning from Manfred, the Astros, according to the results of the information released Monday, used video to decode signs with the help of analysts–a kind of “back room” workaround to the more explicit trash-can system.

The Future

Imagine this scenario in a game in 2020. A batter takes a called strike three with a runner on second base, ending a seven-pitch at-bat. He retreats to the team video room between the dugout and clubhouse to review the at-bat–maybe look for a flaw in his swing or see if that last pitch was indeed over the plate. All perfectly legal.

But what if by watching those seven pitches he decodes the signs the catcher is using with a runner at second base? What if he’s on second base two innings later in a tie game and now he knows what’s coming?

Under Manfred’s edict, such an act would be illegal; it is using video to decode signs during the game. But how is that enforced? And how would a manager or general manager–the ones Manfred holds responsible–even know about such a thing?

Taking it further, what if Band-Aids with buzzers actually become a thing? And who knows how technology will create the next level of sign stealing?

Now that Manfred has swung his hammer, he has to decide on how to assure a corrupt-free game in a high-tech world. The answer is either more technology or less technology, and he’s not sure which path is correct.

“We need to continue to evaluate where we have technology proximate to the dugout and whether there are technology changes that could be helpful in resolving this issue,” he said. “On the one hand you can attack the problem by saying, ‘I’m going to regulate more closely and monitor tougher.’ We will go down that route at least as an interim step to make sure we know exactly what’s going on and make sure people are following the rules.

“Longer term, for example, the idea of having a technology solution that eliminates some guy putting fingers above his cup might be a better answer.”

For instance, MLB has looked into the idea of a series of lights embedded in the pitching rubber visible only to the pitcher. The catcher could be equipped with a device to trigger the appropriate light.

On the other hand, why not eliminate as much technology as possible? If cameras and monitors are causing such subterfuge, why not turn them off as soon as the first pitch is thrown? Video rooms are locked. The only monitor available to a team is the replay one with the MLB security official standing next to it.

“That’s the first path,” Manfred said. “It is an option. We have talked about it. We are not done on 2020 [protocols], no.”

Asked if more protocols will be in place for Opening Day, he replied, “Absolutely.”

Two of baseball’s past three World Series champions created advantages with the misuse of technology. One investigation concluded Monday and another is underway. With his precedent-setting decision Monday, Manfred this time used more than just boldface type to put every club employee on notice as to why baseball’s history of winks and nods is over.

“Whenever you have an allegation that the outcome of a game was altered by a rules violation,” Manfred said, “that falls into the category where fans believe the competition has been affected, and it’s an integrity issue. The integrity of the competition.”