Masks, Fundraisers and Smallpox-Only Teams: How Baseball Has Dealt With Infectious Diseases Before

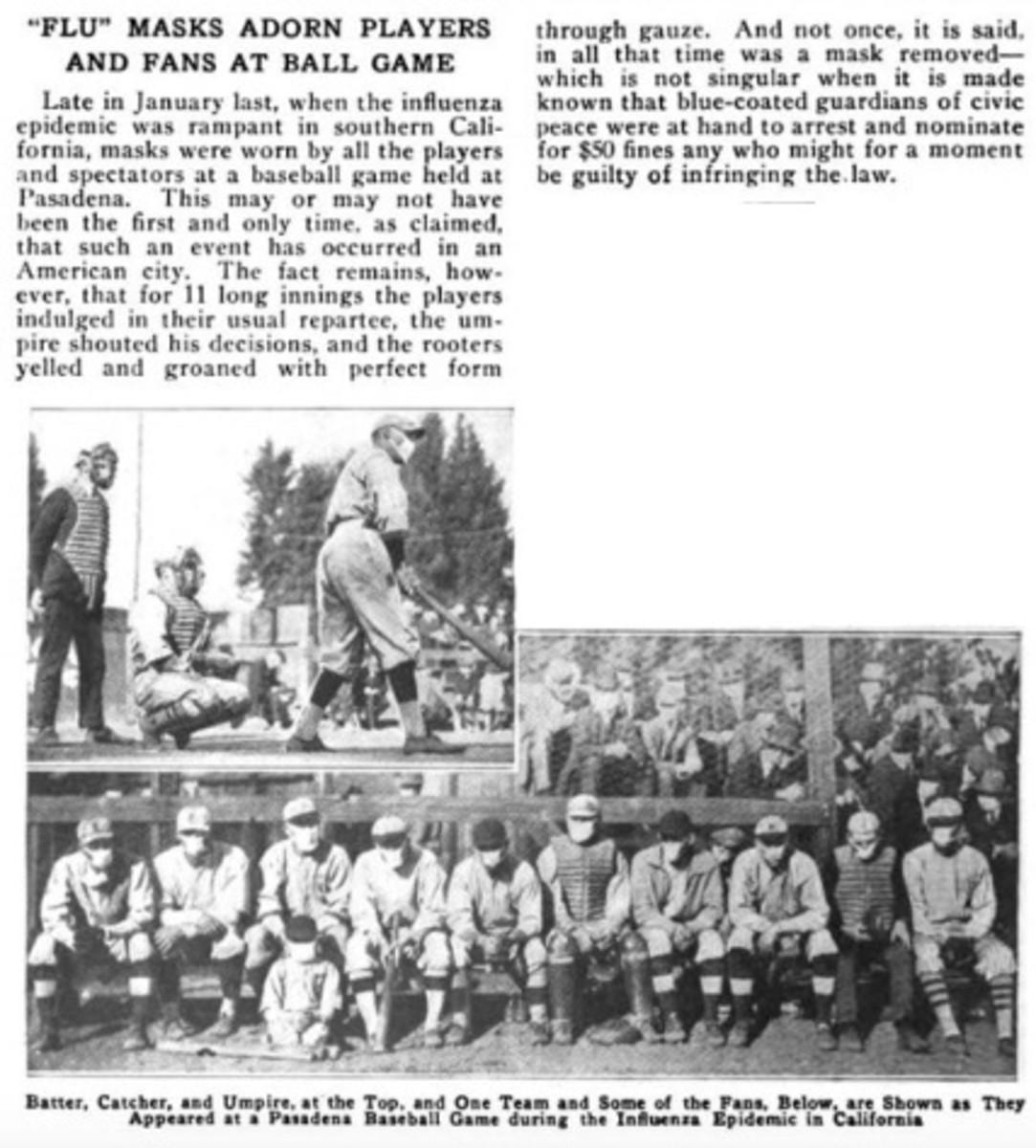

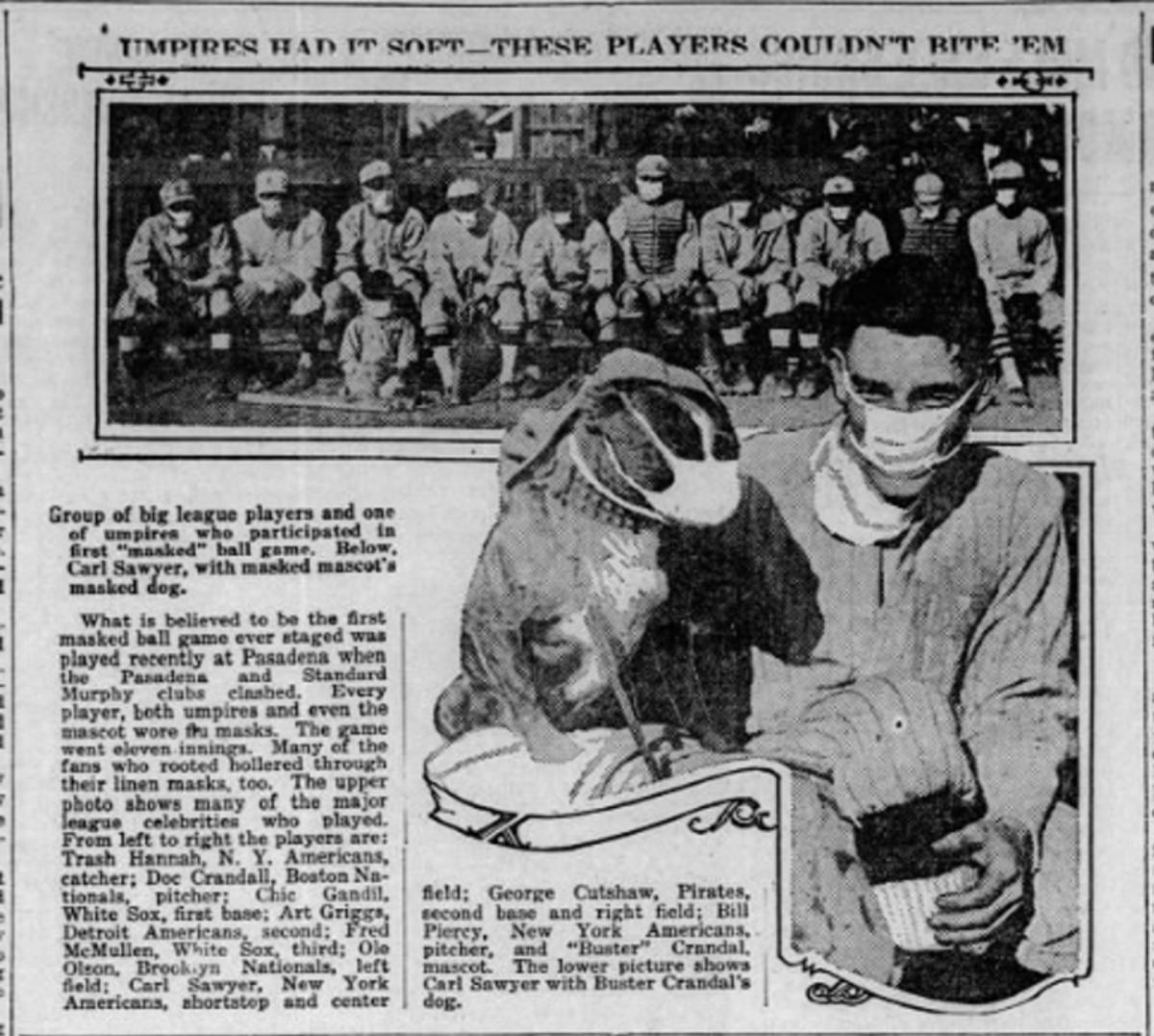

The pictures show an old-school baseball game, typical in every way save one: Everyone wears a mask. There’s a face mask on the hitter, the bench and the crowd. Underneath their standard equipment, the umpire and catcher have them, too.

This is how the Pasadena Merchants and Standard-Murphys played a game in the Southern California Winter League on January 26, 1919. The influenza epidemic that had started the previous year was spreading, and California was concerned. Pasadena had started requiring residents to wear masks in public; on the first day that the rule went into effect, the city made 60 arrests to show that the new law was for real. So how does a baseball team operate under these regulations? Simple: Just make everyone wear a mask. Per the Los Angeles Times, “even when sliding for bases, the runners managed to keep the cloth over their noses and mouths.”

This was not how most baseball teams addressed the flu. While the MLB season was cut a few weeks short in 1918, that was due less to the outbreak and more to World War I, and it started back on schedule in 1919. But MLB went without any formal protocol about how to handle the outbreak, with no serious talk of canceled games or empty stadiums, and baseball went on, even as the illness came for some of its key figures. (It’s worth saying here that there was no commissioner to issue any formal protocol: Kenesaw Mountain Landis didn’t become the first to hold the gig until a year later, as an answer to the Black Sox scandal.)

Now, a century later, the situation is significantly different. As coronavirus has continued to spread, baseball has started to take precautions. MLB has established an internal task force, with no plans to cancel games as of yet, and has sent recommendations to teams about how to handle the situation. Clubs have begun to institute their own safety measures: Tampa Bay has ditched high-fives for toe taps, Minnesota has banned autographs, and Pittsburgh has sanitized their spring training facility out of an “overabundance of caution”. In Japan, NPB spring training is happening in empty arenas and KBO spring games have been canceled in South Korea. Other sporting events have also been played without fans or postponed entirely as every league looks at how to handle the virus.

Baseball, by virtue of its history, has a long record of accommodating outbreak. But even so, there are few examples of professional games that have been canceled, relocated, or closed to fans due to disease. (A notable exception is the 2016 Marlins-Pirates series in Puerto Rico, which was moved to Miami due to Zika virus.) Of course, the current moment is its own; the game is more global, the world understands more about disease, and a closed stadium feels like less of a radical suggestion in an environment where in-person attendance means less than ever. But the history here, if not directly useful, is still rich.

In a sense, baseball owes its origins to disease outbreak, points out MLB historian John Thorn. With the spread of yellow fever and cholera in the decades before the Civil War, adult men could justify playing a game such as baseball as a specifically healthy pursuit, “a ‘manual’ sport rather than a leisurely pastime,” Thorn found in his research for Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game.

As America went in the late 19th and early 20th century, so did baseball. When Maryland was struck with smallpox in 1906, there were reports of smallpox-only baseball teams, for patients who were well enough to play. Three years later, as typhoid fever spread in California, the San Francisco Examiner ran the front-page headline “Epidemic Threatens to Ruin Ball Team” as the Pacific Coast League saw several players fall sick at once. The illness-related charity games have evolved with the times, too: The St. Louis Cardinals had an annual “Tuberculosis Day” game for more than two decades, and years later, President Eisenhower declared “Baseball Polio Day,” when MLB games were used to raise money for the disease on July 4, 1957.

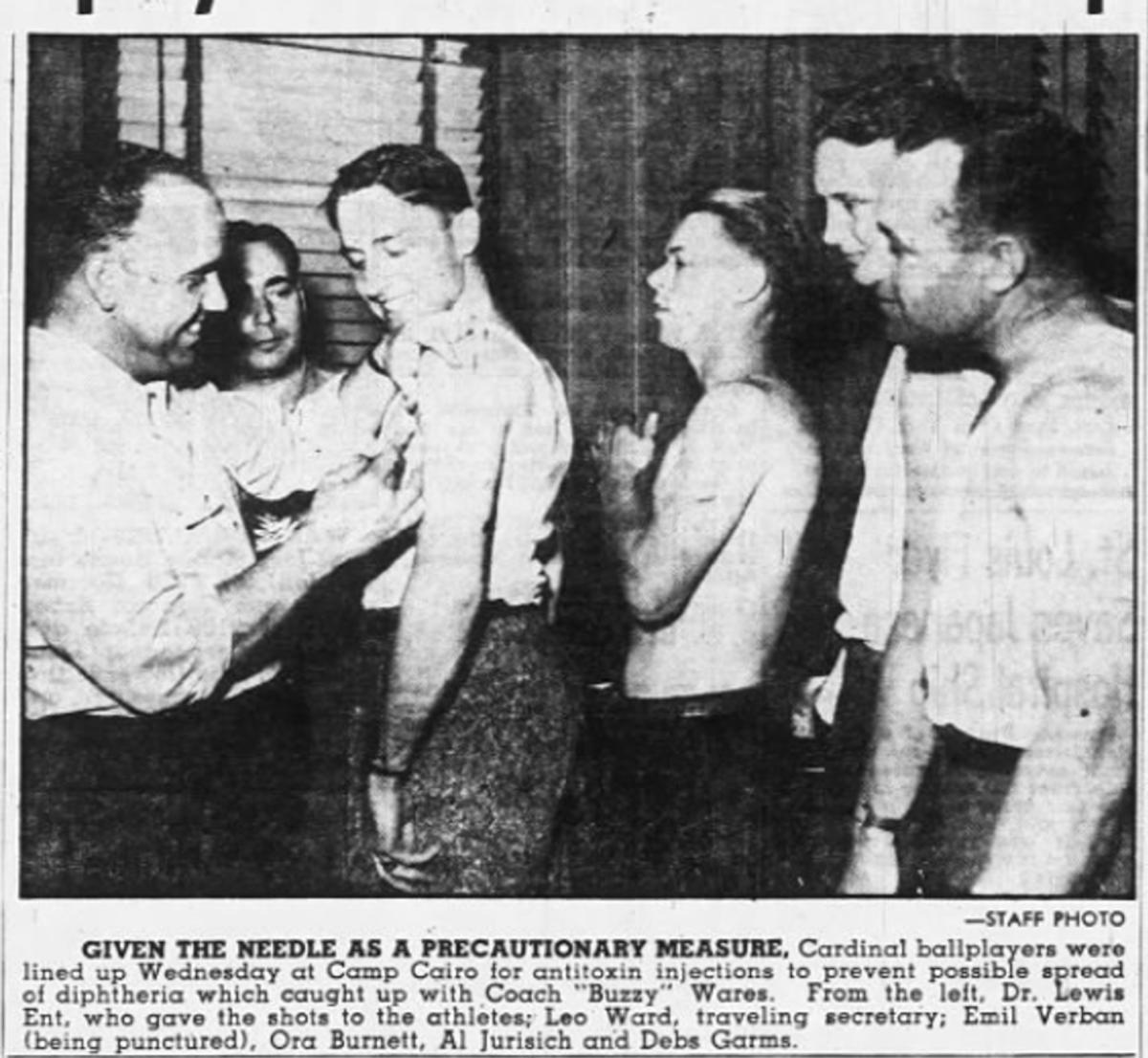

But it was rare to see any unified response to outbreak at the league level. Even when a Cardinals coach fell ill with diphtheria in 1944, the team received antitoxins and braced for a potential quarantine, but there was no official response from Commissioner Kenesaw Landis. At the time, there was no such thing as a league medical adviser—the role used to coordinate with teams on a single response to later outbreaks, such as SARS in 2003.

And as for the 1919 Pasadena Merchants, they appear to be an outlier. While flu masks were common during the outbreak of 1918, there’s not much record of other baseball teams with them, and Pasadena received national press for the novelty of “the masked ballgame.” An especially popular picture in newspapers across the country showed Carl Sawyer, who’d previously played in MLB with the Washington Senators, holding the team’s masked mascot, a dog:

The news at the time described it as the first ballgame played entirely in flu masks, but it now seems likely that it was the only—which it seems that it will remain. Probably.