In Cincinnati, It's Just Thursday

Among the sadder sights in a world without baseball will be the barren stretch of asphalt that is Race Street in downtown Cincinnati at midday Thursday. There will be no marching bands, no pickup trucks carrying grand marshal commissioner Rob Manfred, parade ambassador Johnny Bench and Reds pitchers Sonny Gray and Anthony DeSclafani, no kids cutting school the way their parents and grandparents did, and no restorative powers that come with the return of baseball on a day forecast to be 67 degrees and partly sunny.

Opening Day is the longest-running and perhaps most meaningful societal ritual in American professional sports. Part of its enchantment is the calendar itself. Out from the gelid, gray grip of winter, we are granted official passage into the open, golden arms of spring. We fill ballparks across the country in our zest to—remember this?—gather outdoors in the growing light of day.

Nowhere is this import greater than in Cincinnati. The Queen City is home to baseball’s first professional team and a charter member of the National League, host city for Opening Day baseball 130 times in the past 132 years, and host to an Opening Day parade for the past 130 years, the past 100 of which have been known as the Findlay Market Parade thanks to the support of local shopkeepers. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, there is no parade Thursday.

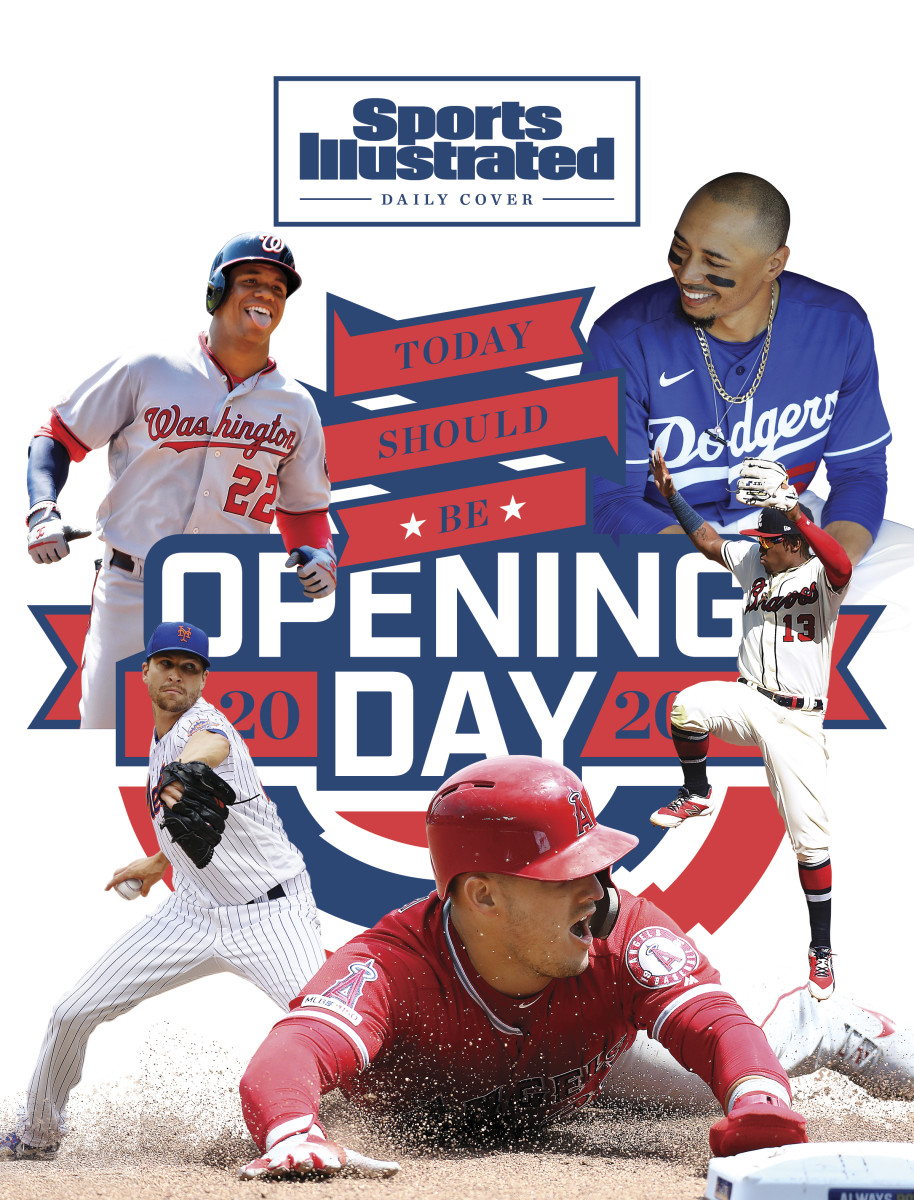

The day was supposed to begin with the defending world champion Nationals playing in New York against the Mets, and the worst team from last year, the Tigers, playing in Cleveland against the Indians. Gerrit Cole will not make his Yankees debut against the Orioles in Baltimore. Christian Yelich will not be back in the Brewers’ lineup against the Cubs in Milwaukee. Anthony Rendon will not make his Angels debut in his hometown, Houston, against those disgraced Astros. The Giants will not renew their rivalry against the Dodgers in Los Angeles. There is no first pitch against the St. Louis Cardinals at 4:10 p.m. at Great American Ball Park. There is no Opening Day.

“It’s terrible,” says Rick Stowe, Reds senior director of clubhouse operations. “I think all of Cincinnati is reeling over it because it’s such a celebration.”

Stowe will spend what would have been Opening Day under quarantine. Immediately after he returned home upon spring training’s shutdown, Stowe was informed that an employee at the team’s Goodyear, Ariz., camp tested positive for the coronavirus. (Stowe is awaiting his own test results.)

“I just got done painting the basement,” he says. “I absolutely love my job and wish we were still playing baseball. It’s not like a 9-to-5 job. Every day is different. I can tell you 12 hours at the ballpark go by a lot faster than 12 hours sitting here at my house.”

Stowe joined the Reds in 1981. His brother, Mark, the clubhouse assistant, has been with the team since ’75. The brothers have followed in the footsteps of their late father, Bernie, the former clubhouse and equipment manager who served the Reds for an astounding 67 Opening Days through his retirement in 2013.

If Cincinnati is the unofficial home of Opening Day, the Stowes are its first family. The Reds have not played a season without a Stowe since 1946, before the game was integrated.

“I remember getting out of school as a kid,” Rick says. “My mom would call up and the nun would say, ‘That’s no problem.’ And Dad would leave two tickets for Sister Mary Walker. It’s like a holiday here. It’s our Christmas, our Easter.”

Among the many kids over the years who cut school for Opening Day was the Reds’ current manager, David Bell, whose brother Mike; father, Buddy; and grandfather, Gus, also played for the Reds. Few franchises boast familial bonds like the Reds—the lineages include not just the Bells, but Boones, Brennamans and Griffeys.

The Stowes predate all of them. Bernie was 12 years old in 1947 when one of his friends, Ralph Tate, turned his ankle and asked him, “Do you want my afterschool job?” The job was visitors’ batboy at Crosley Field. Bernie showed up and never left. He became the Reds’ batboy in 1950, soon graduated to clubhouse attendant and became clubhouse manager in 1968, replacing Chesty Evans, who had held the job for 46 years. He went so far back with the Reds that once, while throwing batting practice, he was chased off the mound by then-manager Rogers Hornsby, who was born in 1898. “You throw like a sissy,” scoffed the curmudgeon.

Bernie retired after the 2013 season as one of the most beloved figures in the team’s long history—Sparky Anderson, the manager of the legendary Big Red Machine, said of Bernie in 1977, “He’s one man we couldn’t replace”—and died three years later, at age 80. His gravestone bears a Reds logo.

The baseball season is a grind. There are 2,430 games in a full major league season, one game for every mile between Oceanside, Calif., and New York City. But Opening Day is an event that stands alone. It’s the first real baseball game in five months. Hopes are highest. Pessimism is lowest. And if you’re the equipment manager, there are literal last-minute alterations to make, even though Rick Stowe and his crew record the measurements of every player in spring training.

“On Opening Day you get guys saying, ‘This just isn’t fitting right,’ ” Stowe says. “Players have butterflies, and the mirrors get used a lot. It’s probably one of our busier days. Once the National Anthem gets going, you feel like you can take a breath of fresh air.”

Opening Day is so special it preserves otherwise mundane moments in amber. In 1987, for instance, Terry Francona hit a fourth-inning home run for the Reds in an 11–5 win over the Expos. Francona, nearly 28 and with two repaired knees, had been signed by Cincinnati that winter. He had hit just nine career homers in more than 1,000 at-bats.

“Terry Francona solidified himself as a hero in Cincinnati that day,” Stowe says.

Francona told a crowd of reporters after the game, “I hope I don’t get any hopes up too much.”

Francona hit his next home run in July. He finished the year with three.

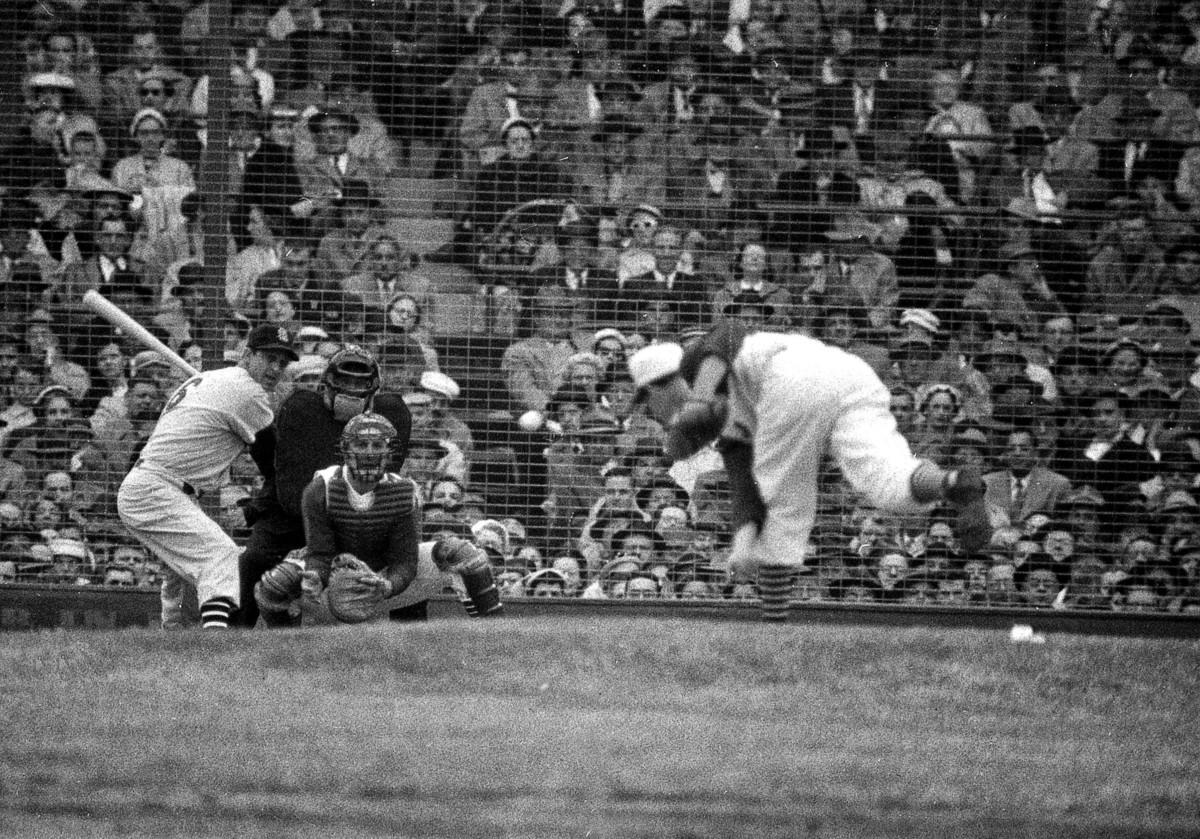

One of Stowe’s earliest Opening Day memories was the ’74 opener, when Hank Aaron homered off Jack Billingham for career home run number 714, tying Babe Ruth. Vice President Gerald Ford attended. Cincinnati rallied from five runs down to win in the 11th inning, 7–6, when Pete Rose scored from second base on a wild pitch.

“Pete was probably one of the few guys I knew that didn’t have butterflies about Opening Day,” Stowe says. “Barry Larkin, I remember asking him one time and he goes, ‘Oh, my gosh, I always get butterflies on Opening Day.’

“The thing I remember about 1974 was talking to Dusty Baker. The team had just gotten back from spring training, and there were tornadoes all over the city. I’ll never forget how scared he was.”

Seven years later Stowe, then 16, joined the Reds as a ball boy, supplying baseballs to home plate umpire Ed Vargo in a game started by Tom Seaver for the Reds and Steve Carlton for the Phillies. The future Hall of Famers dueled for seven innings. With the game tied at one, Seaver left after eight. In the ninth, with the Reds now trailing 2–1, Dave Collins doubled and was singled home, for a tie, by Ken Griffey. Griffey stole second and advanced to third on a wild throw, and after a Dave Concepción strikeout, Philadelphia manager Dallas Green intentionally walked George Foster and Bench to set up a double play. He called for his closer, Tug McGraw, to face Dan Driessen. McGraw walked in the winning run.

“That year Ronald Reagan was supposed to be the first president to throw out the first pitch in Cincinnati,” Stowe says. Reagan was in a Washington hospital, having been shot nine days earlier in an assassination attempt.

So long have the Reds hosted Opening Day that the tradition’s roots are lost in history. Baseball’s Opening Day became an event at the end of the 19th century when a rival to the National League, the American Association, created competition. (The Cincinnati franchise played in the AA from 1882–89). The Reds may have been granted the annual honor of opening at home because they were the southernmost franchise at the time, offering the prospect of better weather. When they rejoined the National League in 1890, their business manager, Frank Bancroft, so fervently promoted Opening Day and its festivities that he became known as “The Father of Opening Day.” His promotions included the first parade in 1890. It included three streetcars: one carrying the Reds; one carrying their Opening Day opponents, the Chicago Colts; and one carrying a band.

Only twice since 1888 have the Reds played Opening Day on the road: 1966, due to several days of rain, and ’90, due to the 32-day lockout.

“We started in Houston in ’90,” Stowe says. “We played our first [six] on the road. That was after Pete was banned from baseball. Lou [Piniella] was our manager. We came home [6–0]. That turned out to be a pretty good year for us.”

Cincinnati led the NL West every day of the season and won the World Series, one of only five such teams to go wire-to-wire.

Labor strife hit baseball again five years later. With players on strike since August of the previous year, teams prepared to open the 1995 season with replacement players. Among the replacement Reds were a bread-truck driver and the owner of a packaging business. Cincinnati made a five-for-none trade with Cleveland, acquiring five replacements from the Indians in return for nothing, prompting Reds manager Davey Johnson to quip, “Cleveland got the better of the deal. They didn’t get anybody.”

On the eve of Opening Day, just before a workout at Riverfront Stadium, Cincinnati replacement players learned of a ruling by Judge Sonia Sotomayor in favor of the players, effectively ending the strike.

“I got a call telling me to pass out garbage bags,” Stowe says. “The garbage bags were for the replacement players to pack up their stuff. We sure weren’t handing out duffel bags. I remember when the other guys came back, they were talking like if the replacements played Opening Day, it wouldn’t have been long before they crossed the [picket] line.”

The next Opening Day, April Fool’s Day 1996, was the first for Rick upon taking over duties as equipment manager from his father, though the title would become official the following year. The day brought unimagined tragedy. After a morning snowfall, the game began on time against Montreal. Umpire John McSherry took his place behind the plate. McSherry had complained in the preceding days about an irregular heartbeat. Fellow umpires advised him to skip the game and see a doctor. He said he would do so after Opening Day, on the scheduled off day.

Seven pitches into the game, McSherry collapsed behind the plate. He was pronounced dead less than an hour later. He was 51 years old.

“Ray Knight was our manager,” Stowe says. “Felipe Alou was the manager of the Expos. There was a conversation in our clubhouse. ‘Should we play the game? There are 50,000 people out there.’ Ray Knight was going around asking the players what they thought. Then Reggie Sanders, who didn’t say much, made a tearful plea. He said, ‘We don’t play this game.’ We ended up canceling it. We played the next day.”

Reds owner Marge Schott made known her unhappiness, as well as her selfishness.

“I feel cheated,” Schott says. “This isn’t supposed to happen to us, not in Cincinnati. This is our day. This our history, our tradition, our team. Nobody feels worse than me.”

The next day, according to the Dayton Daily News, Schott took an Opening Day floral arrangement sent to her by a local television affiliate, scratched out a message on a new card and sent it to the umpires’ dressing room. The Reds beat Montreal, 4–1.

Two years later, in 1998, the Reds neared the end of a training session on the eve of Opening Day when general manager Jim Bowden called Stowe in his clubhouse office.

“Hey, I need you to do me a favor,” Bowden told Stowe. “Go around the players and act like you’re getting phone numbers. I really just need Dave Burba’s number.”

Burba was scheduled to be Cincinnati’s Opening Day starter the next day. He was on the field.

“Oh, and get me Mike Remlinger’s number, too,” Bowden says. “Get a few guys. Act like you’re just getting numbers. But I only need Burba and Remlinger. Remlinger is going to be the Opening Day starter. We’re trading Burba for Sean Casey.”

Last year brought another one of those moments that will linger forever, just because it happened on Opening Day’s well-lit stage. The Reds and Pirates were tied 2–2 in the seventh inning. Cincinnati had runners at second and third. Bell needed a hitter to bat for his pitcher against Pittsburgh reliever Richard Rodríguez. He called on Derek Dietrich, who had signed a minor league contract with Cincinnati that February. In his first at bat for the Reds, Dietrich smashed a three-run homer. Cincinnati won, 5-3.

Dietrich joined Dick Simpson as the only Reds to hit a pinch-hit homer in an Opening Day win. Simpson hit his home run on Opening Day 1967. He never hit another one that year, or again for Cincinnati. Simpson was traded seven times in five years, including the famous one in December 1965, in which the Reds sent Frank Robinson to Baltimore for Milt Pappas and Simpson, who was given Robinson’s No. 20.

“That’s what’s special about Opening Day,” Stowe says. “Like Terry Francona in 1987, you get Derek Dietrich last year.

“There’s nothing like Opening Day in Cincinnati, with the parade and all the pomp and circumstance. It’s bigger than any city I’ve been in, and I’ve been in a lot for their Opening Days. St. Louis does a pretty good job, but there’s nothing like Cincinnati.”

Leave it to Anderson, with his Twain-like wit and Berra-like syntax, to capture the homespun poetry of what Opening Day means in Cincinnati. “It’s a holiday—a baseball holiday!” Sparky once said. “Ain’t no other place in America got that.”

We’ve known for two weeks this day was coming. But now we actually feel the absence, like a phantom limb—the absence of Opening Day, of our rituals, of our gathering, of the very hope Opening Day represents. There is no holiday.

Under quarantine, Rick Stowe will try to make do. “I’m thinking about putting furniture on the back deck and setting up the TV to watch a rerun of a game,” he says. “I might even have a beer. I hear it’s going to be a nice day.”