How the Internet Created a Sports-Card Boom—and Why the Pandemic Is Fueling It

At noon on April 27, Chris Justice did what he does at noon every weekday: He turned on a live camera feed and stood in front of a sealed box. The North Carolina resident rotated it for the audience, displaying each of its blank cardboard sides, a confirmation that there had been no tampering with the packaging. Then, in one smooth motion, he sliced it open and emptied its contents out onto the table: 10 plastic-wrapped boxes of Topps 2020 Gypsy Queen baseball cards. That’s 24 gleaming packs per box, eight cards per pack, 1,920 cards in total—and Justice was going to spend the afternoon with them.

His routine is part work and part treasure hunt, both personal ritual and public performance. Justice opens new cards each day—baseball, football, basketball, sometimes hockey, Topps, Upper Deck, Panini—and livestreams the whole affair on YouTube and Twitter, providing play-by-play that lends each afternoon its own cadence. With a specialty pack, Justice will flip slowly, lingering on the details of each card and identifying each player. For more usual fare, he’ll expertly scan a handful in a matter of seconds, pausing only to call out the choicest few.

The camera remains focused on his hands and what they hold—Justice is the narrator, and the only human presence, but the cards are the stars of the show. Some viewers have more than a casual interest: Before a “break,” as this is called, people can sign up to buy a selection of the cards that will be opened, usually all the players on a specific team. Land on a particularly valuable insert, and you’ve got jackpot. During a typical livestream, the chat will buzz with viewers’ jokes and commentary, and Justice will open pack after pack until he’s done for the day, which will be at least a few hours and can stretch well into the evening.

A feed focused on a man’s hands flipping through sports cards for hours on end may not be exactly what you’d think of as prime-time entertainment. But, for thousands every day, it is.

Justice, who was one of the first breakers when he started out in 2007, sells out just about every box that he lists. About 2,000 people watch each of his breaks, and collectively, his videos have been viewed more than 60 million times on YouTube, plus more on Twitter and the breaker-specific video service Breakers TV.

“I was one of the only ones [at first],” says Justice, whose operation is called Cards Infinity. “Five years later, there were hundreds trying to do it, and now, it’s way more than hundreds.” Breaks have transformed the sports-card industry—saving it from low sales at the end of the last decade, giving it a foothold in online culture and bringing cards to younger consumers.

And now, amid a pandemic that has kept Americans home and canceled all sports, breaks are experiencing a new surge in interest. Since the coronavirus shut down regular daily life in mid-March, Justice says he has seen a 25% increase in overall business and a 15-20% increase in new customers. His breaks have almost doubled in viewership. Other breakers have seen similar shifts. With no live sports, no fantasy sports, and plenty of demand for distraction, breaks have won a new audience.

“It just exploded," says Rich Layton, whose Florida-based Layton Sports Cards has seen viewership increase by 25%, with 800 new people signing up for the rewards program that he runs for frequent buyers. “And it’s been nonstop ever since.”

***

Here’s how it works. Say you want some cards—but only certain ones, not just the random assortment that comes in a lone pack. Maybe you’re hunting for one of those rare inserts, or you’re a die-hard Detroit fan who only wants Tigers, or you want to access a portion of an expensive specialty set. You find the website of someone like Justice or Layton, which will list cases of cards at all sorts of price points. You buy into what’s called a “group break”: a case broken open for a group of people who will share the cards. This is frequently done by team: You sign up to buy all the Red Sox cards, someone else will sign up for the Yankees, and, at cheaper prices, others will sign up for the Royals and Rays, and so on. But cases can be divided by boxes, or done randomly, until individual slots have been sold for the entire set. Then, the breaker does his thing while you watch, hoping for your cards to shuffle across the screen.

After the camera is off, the breaker will sort the contents of the boxes and mail cards to their buyers.But the audience is not limited to those who buy—far from it.

“We have a large following of people who don’t buy into our breaks at all but watch us religiously,” says Layton, who’s been in the break business since 2012. “They just like seeing cards being opened. They like seeing the reaction—the natural reaction to something big being pulled.”

That creates an environment of regulars, people logging on to watch the same breaker day after day, whether or not they’re buying. “It’s like Cheers. You walk in the bar, everybody knows your name,” says Larry Franco, who has run LiveCaseBreak since 2010. Like Justice and Layton, he’s seen a sizable recent boost, with April ranking as one of his busiest months ever as views rise by 20–30%.

Breaking offers routine; it creates community; it takes a simple act and makes it a type of entertainment unto itself. And it’s growing.

***

The recent boost has been considerable for breakers. But they didn’t need it to firmly establish their spot in the industry. That’s been hard won over the last decade.

"When we first started, everyone hated us,” says Michael Hodges, who started the Clubhouse Breaks in 2010, when the practice was still relatively new. “We were the rebels who were closing card shops, with everything online, and so no one really gave us the time of day. And now, 10 years later, we have deep relationships with Topps, Panini, all the manufacturers across the whole supply chain.”

Maybe the best proof of these relationships came just before the current spike in interest, back in February. A group of 19 breakers gathered in the Dallas Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium: Justice, Layton, Franco, Hodges, and more than a dozen others, the biggest names in breaking. They spread out on the suite level, with each at their own table. This was the structure for the world’s largest group break: They were going to open one million cards.

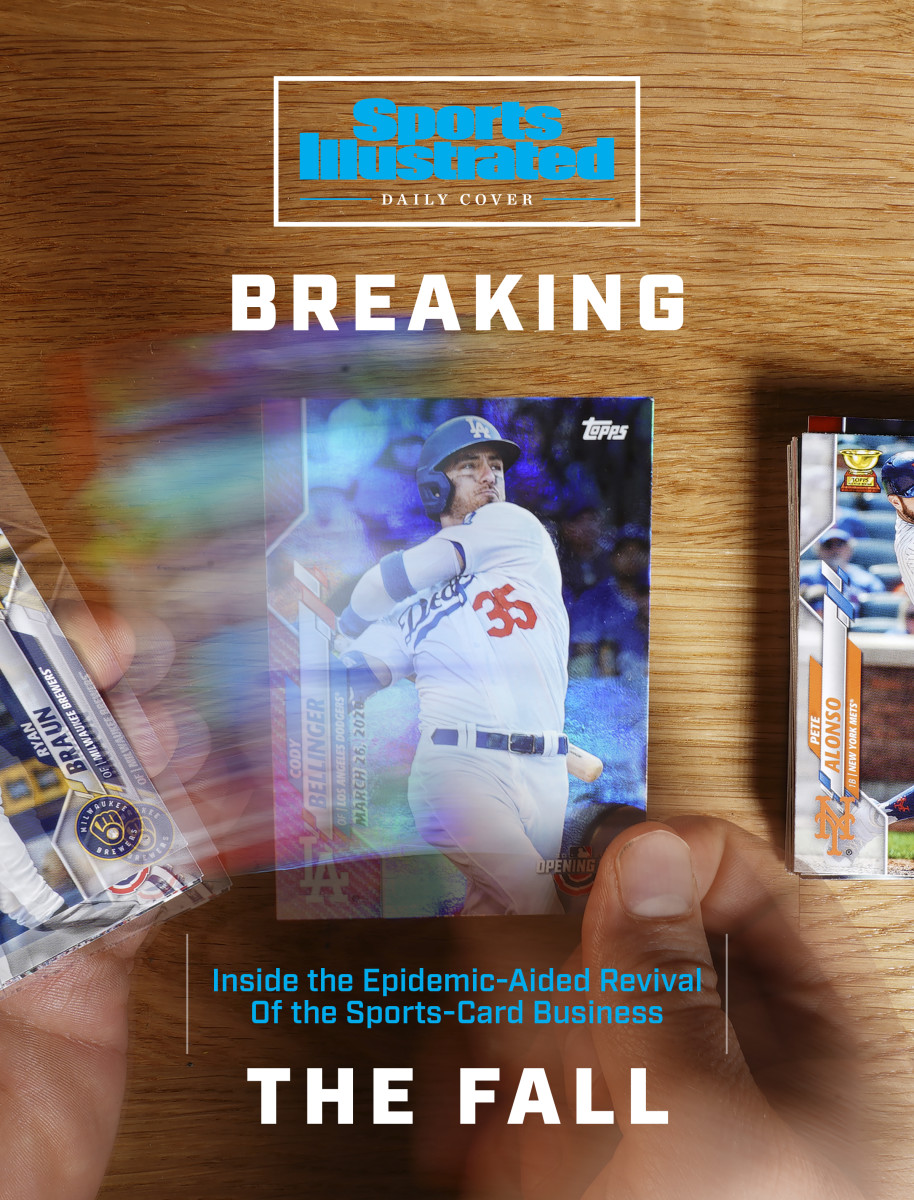

Topps had organized the event—its largest official partnership ever with breakers—and provided them with all one million cards to promote the official launch of its new releases for 2020. The company had even brought in a guest for the ceremonial first pack: Mets slugger Pete Alonso. After being presented a pack on a little satin pillow, he went for the most creative rip of the day by tearing it open with his teeth. If breakers had once worked on the fringes of the industry, Dallas was evidence that they’d not only made it to the mainstream, they’d become the energy behind the entire business.

“We wanted to start a new decade of Topps by looking towards the future,” says Emily Kless, Topps’ communications manager and MC of the event. “And we believe that box-breaking is really the future of card collecting. They’ve just changed the game, the way that people collect cards, and they’ve made it a group activity again.”

Even with 19 people opening them, a million cards takes a long time—about nine and a half hours, it turns out. And to see all the breakers ripping at once was to see the full breadth of the industry.

Some announce their breaks in voices fit for radio. Some record in gentle tones that make their feed feel more suited for ASMR. There are breakers who try to make their stream kid-friendly and breakers who don’t. There are some who go with dramatic celebrations for big pulls, others who barely let them register, some who banter and crack jokes, others who zero in on the cards themselves. There are breakers who rip the packs slowly, giving viewers a moment to luxuriate in each anticipatory crinkle of the foil, and breakers who go in one smooth motion and toss the wrapper to the floor. Some focus on their hands; some have the camera on their faces. The 19 tables showed it all.

“Every collector wants something different,” says Ryan Holland, who has run Real Breaks Live from Minnesota since 2017. “Some collectors want you to go really fast and only show the biggest cards, and some collectors want you to take your time and go really slow. We try to create an environment where it’s the pace of how you would hang out with your friends, so we’re not trying to fly through and get done as fast as we can. ... Every breaker has a different strategy, and I think most people are pretty intentional about it.”

Justice calls his strategy “breeze to the hits”—skim, skim, skim until he lands a notable card to call out. It’s a style he’s been honing since 2006, when all this started.

***

Back then, Justice was operating a brick-and-mortar card shop in Wilmington, N.C., when he noticed a fellow storeowner, Rick Dalesandro of New Jersey—better known by his card nickname of “Dr. Wax Battle”—posting videos of himself ripping packs. Justice loved it. He asked some of his customers if they wanted to try—they’d come into the store to buy their usual packs and then take a minute to rip them open on camera. It was a hit. So in 2007, Justice decided to expand the system for viewers who didn’t live nearby: He’d post a case online, let people buy slots in it in advance, so that he could break it for them, and then post the video. And, lo, group breaks were born.

He still has his brick-and-mortar shop today, but the bulk of his business, by far, is online. His origin story separates him from most of the breakers who came after him: They were not the people who owned card stores. They were the people who were disrupting card stores.

That included Franco of LiveCaseBreak, who started in 2010, after trying to find specific football cards for his son Cameron. “I was buying box after box after box of cards, trying to get him Cam Newton,” he recalled. So when the South Florida resident found an early example of an NFL group break to buy Panthers cards—recorded videos and no live chat, thanks to the tech of the time—he knew it was special. “I knew instantly, at that moment in time, this was going to change,” he says. “The whole way cards were going to be collected was going to change because of this idea.” He reached out to the guy who had organized the break, and the two have been in business ever since.

Breaks remained somewhat niche for a few more years; an established playbook for new breakers wouldn’t exist for a while. When Layton began in 2012, it still felt like the Wild West. “When I started, man, I had no idea what I was doing,” he says. “We were just guessing our way through.” He was an avid card fan who worked as a carpenter, opening packs at his kitchen table at night as his wife helped him sort. He’d get frustrated by the amount of time it took to upload a video to YouTube. But after a year, he’d found an audience that allowed him to break full-time, and now, it’s big enough that he has seven employees to run the business with him.

“Everything is different now,” he says. “The technology has changed, the viewership has changed—the size of the breaks, the size of the crowd that wants to get into the breaks, everything is bigger, everything is faster. And over the last year or so, manufacturers are now recognizing breaking as a legitimate thing.”

The rise of breakers over the decade has contributed to the rise of cards themselves. When Justice started in 2007, sports cards were at a low point, an analog pastime that was struggling to attract new fans.

“We saw the hobby dipping and interest waning a bit in the late 2000s, 2010, 2011, especially among young consumers,” says David Leiner, Topps’ general manager of global sports and entertainment. “We saw that demographic just aging, 35 to 55 turning into 40 to 60. We had a core base, but we weren’t getting young consumers involved.”

That trend has reversed in the last few years. While the baseball card industry fell from domestic sales of $1 billion in the '80s and early '90s to $200 million in 2012, Leiner says that it's now bounced back to the strongest position that it's had in two decades (though he declined to share Topps' sales numbers). That isn’t just from breaking—sales have also increased in other forms of online retail, as well as at big-box stores like Target and Walmart. A card market that’s forever been driven by rookies has met a world where even casual fans can easily track prospects as they progress through the minors to their major league debut. As was the case during the industry’s pre-internet heyday, some collectors have also embraced cards as a serious alternative investment. But the renaissance has been especially driven by breaks, pushing the hobby into a new form of entertainment.

“It’s pretty much reenergized the whole market of how sports cards are moved,” Justice says of the suddenly growing interest in cards. “It brings so much attention to the hobby. More people get to see it. It builds; it makes it grow. Right now, it’s the highest I’ve ever seen it—’87 to ’91, it was super big before it collapsed, but this is the biggest I’ve ever seen it.”

***

The Million-Card Rip Party lived up to its name: 1,002,456 cards from more than 21,000 individual packs. Most of those, of course, were opened by the breakers themselves. But a few went out to the people around the edges of the party—the support staff, the card media, the small handful of hardcore fans in attendance.

Like Rich Klein, a Texas man and veteran card collector. He still remembers the first pack that he opened: 1968, Topps third series, when he was eight years old—cards that he saved and revered. “In those days,” he says, “it was really one of the few ways you had a physical way to see what the players looked like.” Now, he’s looked at cards for decades, has worked in the industry, and has a personal collection of tens of thousands. But he still paused in delight before a breaker offered him a pack to rip in Dallas.

“It’s just fun to open. There’s a joy about opening the pack, not knowing what you’re getting,” Klein says. “It’s a lottery ticket. You hope you get something really good, but on the other hand, you’re not necessarily worrying about that when you’re opening the package. You just want to enjoy it. It's absolutely beautiful.”

"These cards talk to you. They talk to everybody in different ways.”

That energy has created some of the force behind the recent boost for breakers. Right now, there are people in search of sports, people in search of conversation, and people in search of the sensation of a lottery ticket. And breaks can be all of that.

“I think we’re an outlet for a lot of people right now that we weren’t before,” says Kyle Rino, another breaker who was invited to the February party in Dallas. This is the busiest month that he’s had since he started Monster Breaks in Illinois in 2014. “Right now, we’re kind of like their last thread to sports. ... It’s exciting, because you never know what’s going to come out. And people get intrigued by that—where sports talk radio, it’s kind of repetitive now, this brings a bit of excitement.”

For some, breaking provides the rush of daily fantasy or gambling. You typically buy into a break for a fixed dollar amount, but if your section of the box includes a particularly valuable card, such as a special insert or autograph, then you’ve more than earned back your money. If not, well, maybe you’ll put cash down for more cards tomorrow.

But many have found appeal in just sitting and watching—even those who didn't previously collect cards, or, at least, hadn’t collected since childhood. Breaks may not be sports, but they’re sports-adjacent. They offer consistent fresh material. Each day offers the same characters with different outcomes. And while this, like every other hobby currently enjoying a renaissance, is necessarily done alone at home, it still provides a sense of shared experience and community.

“We’re kind of like a sports bar now,” jokes Chris McVay, who started Buck City Breaks with his childhood friend Adam Colvin in Columbus, Ohio, in 2017. They hit record sales in March and were on track for even more in April. “We have 200-plus people in the chat at any given time who are just in there talking about sports. ... You can’t go out to a sports bar anymore, so we’ve kind of become that. Sit down, whatever beverage you want, BYOB, watch the breaks, and talk.”

Each breaker attracts their own audience, with viewers gravitating to different ones depending on their desire for banter or flashiness or more serious card talk. But even with this variety, almost all of the chatrooms feel like a relic from an older, purer, more earnest internet: regulars greeting each other by name, erupting in excitement when someone else lands a cool card, generally being helpful and friendly. “Cards are just the thing that we all have in common,” says Hodges. “But people, every night, they just want to hang out, they want to talk, they want to experience other people.”