Michael Jordan Chose Baseball. Baseball Never Chose Him Back

Michael Jordan was headed to the major leagues.

That is not the common historical take on his 1994 abscondence from the NBA to minor league baseball. Playing for the Double A Birmingham Barons of the White Sox organization, Jordan showed a roller coaster of a swing (long, loopy and daunting), batted .202, and was so green he didn’t know which base to throw to nor the difference between a two-seam fastball and a four-seam fastball.

The popular narrative took deep root because of rough first impressions (shocker! Jordan was 31 years old and had not played since high school) and the harrumphs of the hidebound baseball establishment that did not take kindly to someone who “didn’t pay his dues” and was regarded as a celebrity interloper.

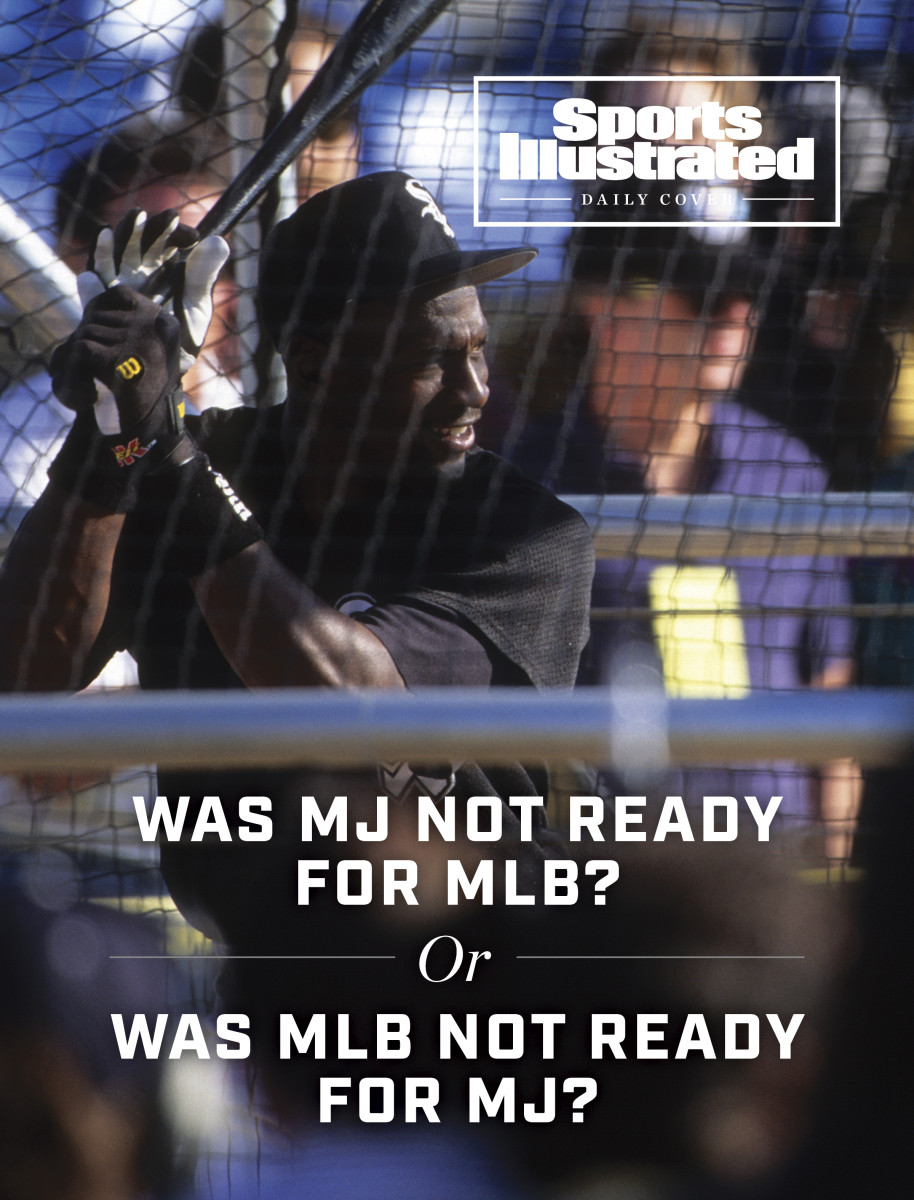

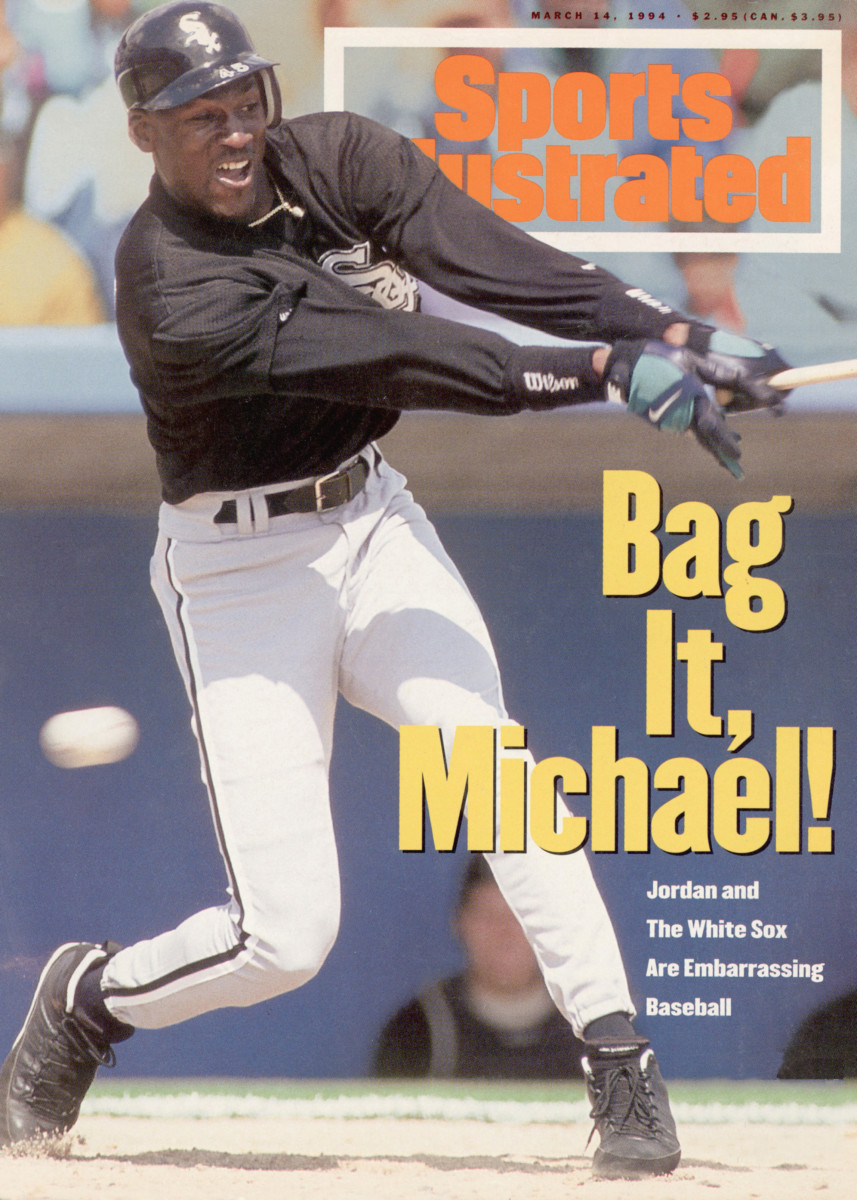

“Let’s make sure we include baseball journalism in that assessment,” says Sandy Alderson, the Oakland A’s general manager at the time. “They tend to be … let’s say conservative on baseball issues. Remember the SI cover?”

Jordan had played for only three weeks in training camp when SI ran a cover story by Steve Wulf under this heading: “Bag it, Michael! Jordan and the White Sox are Embarrassing Baseball.”

The longer view tells a different story. Jordan was becoming a big leaguer the way most minor leaguers do: unglamorously, by grinding at the game, making adjustments and accumulating wisdom with every failure and every 10-hour bus ride.

Jordan, for instance, batted .276 in August. After his season in Double A, Jordan hit a very respectable .252 in the Arizona Fall League, a developmental league for the top prospects in each organization. (Mike Trout hit .245 in the AFL in 2011, his third pro season.) I saw Jordan play in the AFL. While his swing mechanics stifled any power (“the most celebrated minor league singles hitter in history,” I called him), he showed me big league promise. I wrote then:

“He is good enough and dedicated enough that his quest to reach the big leagues – at least as the 25th player on the White Sox roster – has a shred of legitimacy to it. There is something there … He has not been an embarrassment to the sport, as this magazine suggested in March.”

That infamous .202 batting average in Birmingham requires closer examination. Jordan showed a knack for driving in runs, an understanding of the strike zone and a fearlessness on the bases, all qualities a scout would consider barometers of future success.

Jordan totaled 51 runs batted in, 51 walks and 30 stolen bases. How impressive is that combination? Over the previous four seasons, there have been 1,218 player/years in the White Sox organization, majors and minors included. None of them reached the thresholds of RBIs, walks and stolen bases that marked Jordan’s year at Birmingham.

Take a longer view to further appreciate what Jordan did in his first year in pro ball. Over the past 30 seasons (1990–2019), there were roughly 8,000 player/years in the White Sox organization. Among all those yearly statistical lines, which include combined minor league stats for players at multiple levels, Jordan is one of only nine players to reach 51 RBIs, 51 walks and 30 stolen bases. Five of those nine players reached the big leagues.

“I’m glad you said that,” says Indians manager Terry Francona, his manager in Birmingham and the AFL. “That’s what I’ve been trying to say about him. Obviously, I like the guy. I care about the guy. What he really did the best was learning about the game. He couldn’t ask enough questions. He was getting better and better.”

I asked Francona whether Jordan was on his way to becoming a major leaguer.

“Yes,” says Francona. “I found out a couple of things about Michael. Number one, if you tell him ‘no’ he’ll find a way to make it ‘yes.’ And if you gave him three years—1,500 at-bats—he could find his way to the big leagues. I’m pretty sure about that.”

Jordan announced his retirement from basketball on Oct. 6, 1993. The next month Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of the Bulls and White Sox, told White Sox general manager Ron Schueler to expect a call from Jordan.

“He wants to start training for baseball,” Reinsdorf told Schueler. “Make the place available to him, but don’t make him any promises.”

In the last week of November, Jordan called Schueler.

“I’d like to take some swings in the batting cage,” Jordan told him.

After two weeks, Schueler knew Jordan wasn’t engaging in a lark but was serious about playing baseball. Word leaked out about Jordan’s plans. Alderson called up David Falk, Jordan’s agent, with a contract offer from the A’s.

“We’ll put him on the major league roster,” Alderson told Falk. “He won’t have to play in the minors. He’s on our 25-man Opening Day roster.”

Falk did his level best to give a neutral response. He gave nothing away as to how the promise of a big league job would go over with Jordan. Alderson didn’t hear back. He began hearing rumors that Jordan was interested in signing with the White Sox. Then he heard from another baseball source that the White Sox were unhappy about Alderson’s offer to Jordan. On Feb. 7, 1994, the White Sox announced they signed Jordan to a minor league contract.

At the time Oakland was coming off a 94-loss, last-place season in the American League West. The A’s ranked 21st out of 28 teams in attendance. They still had manager Tony La Russa, outfielder Rickey Henderson and first baseman Mark McGwire, but their glory days were long gone. Did Alderson offer Jordan a major league roster spot simply as a cheap way to boost attendance and revenue?

“I never started to quantify it,” Alderson says. “I knew it would be better, but I wasn’t trying to quantify it. I knew we’d improve our attendance, yeah. But mostly I thought this would be fun. It wasn’t about the money. It was more, ‘Won’t this be fun?’

“What made the teams we had in the late ’80s was that they were so much fun. Yes, we won championships. But it was the personalities as much as the abilities and success that you remember. That’s what made it fun. It was not like we were the Big Red Machine just grinding it out.

“I think [the offer] was the sense not that it would be good for the game in any sort of significant cultural way. But that it was about the notoriety and the celebrity that surrounded him—the notion that baseball is a game that ought not to take itself so seriously. It was sort of a ‘why not?’ question for me.”

With Oakland, Alderson had drafted NBA star Kevin Johnson and NFL quarterback Rodney Peete before they established their careers in other sports. He signed a military pilot who served in Operation Desert Storm and a Marine who lost a pinkie in Iraq. As Mets general manager, he signed Tim Tebow.

“Those weren’t public relation stunts,” Alderson says. “They are kind of a recognition that the game should be available to a variety of people with a variety of backgrounds who love the game.”

The baseball establishment criticized the White Sox for assigning Jordan to Double A. What about all the fringe players trying to fight their way out of A ball, they asked? Wasn’t Chicago impeding the chance of a legitimate ballplayer by kowtowing to a celebrity? Alderson would have faced the same backlash had he put Jordan on the Athletics’ roster.

“The job of the 25th man is temporary,” Alderson says. “That ‘person’ is interchangeable with five, six, 10 others. Saying someone is losing a spot is overstating the case. Ultimately it would not have had a major impact.”

Jordan worked with famed White Sox major league hitting instructor Walt Hriniak, which was the equivalent of an elementary school student taking advanced calculus. Jordan didn’t have a basic understanding of hitting. Hriniak’s idiosyncratic, technical methods escaped Jordan. So inexperienced was Jordan that after one spring training at bat a teammate asked him, “What was that pitch? A two-seamer or four-seamer?” and Jordan replied, “What’s that?”

When the White Sox assigned Jordan to Birmingham at the end of March, Francona, the Barons’ manager, immediately thought of the media and fan attention, wondered about Jordan’s intentions, and thought, Uh-oh, this is not good.

“We talked that first day,” Francona says. “We talked back and forth. I told him, ‘I’ve got 24 kids who are trying to get to the big leagues and it’s my job to help them. This is all I’ve ever done. All I’ve ever done is be in baseball. I don’t know anything else.’

“Right away he convinced me he was there for the same reasons. To watch him respect the game and the people in baseball. … Man, I’m telling you that made me want to be really protective of him because others were so critical of him.”

Rumors flew that Jordan was playing baseball only as part of a forced exile from the NBA over concerns about his gambling habits.

“Michael was playing for the right reasons,” Francona says. “The whispers that he was there for not the right reasons kind of bothered me.

“I knew why he was playing baseball. I knew his intention. And it was pure. He made himself a member of the Birmingham Barons in every way. He won over everybody.

“I think he had gotten run down by the NBA and all the media scrutiny. He was worn out. And also because of the conversations he had with his dad before he died. His dad loved baseball. He had time to reflect on it a little bit and said, ‘To hell with it.’

“Because of Jerry Reinsdorf, there was a doorway into baseball. It just kind of worked out. And when he did it, he did it full speed. There were so many times he could have said, ‘I’m going to miss the bus’ or ‘I’m not staying at the La Quinta’ or ‘I’m not coming out early for BP’ Not once did he miss anything. Not once.”

Jordan loved the camaraderie of baseball. In the NBA, players showed up at the arena when they had to and scattered quickly after the game. He noticed baseball players shared hours and hours of unhurried leisure time at the ballpark. Jordan loved playing cards and Yahtzee in the clubhouse before games and lingering after them to talk baseball with teammates.

“I like spending time in the clubhouse with the guys,” Jordan said to a group of reporters, including me, during his time in the AFL. “That doesn’t happen in basketball. Guys clear out. The other night we stayed up until one o’clock in the morning playing cards. I love that. I can’t do that outside the clubhouse.”

Jordan lived in a rented private home with its own golf course and made sure to play at least five other upscale courses around Birmingham. He didn’t buy the team a $350,000 bus, as the urban legend has it, but it was because of his celebrity that a bus company provided it. The bus, known as the Jordan Cruiser, had a semicircular couch in the back so Jordan could stretch his legs, but he was more comfortable in a regular seat with the guys. Teammates loved him because in the ways that truly mattered in a clubhouse—what kind of teammate are you?—he was just another hustling bush leaguer pulling down $850 a month.

Players and staff occasionally played pickup basketball games at Rime Village, an apartment complex where many of them lived. On the modest outdoor court they saw the famed Jordan competitive streak they had seen on TV in the NBA Finals. Once, Jordan’s team trailed 15–11 in a game to 16, win by two. Jordan turned serious, vowing his opponent would not score again. His team won, 17–15. The game, which began with no one around, ended with people ringing the court. Even before cellphones, word traveled fast when the word was Michael.

“Another time Michael had this 6'6'' pitcher guarding him,” Francona says. “Michael was getting pissed a little at one point. He has the ball underneath his arm and he goes, ‘I’m going right here.’ He leaves his feet and I’m going, ‘Oh, no, this is not good.’ He slams the ball through the rim. Next thing you know the rim is bent and he’s standing over the guy, who’s on the ground.

“Everywhere we went, he drew a crowd. We couldn’t play one of those games without all kinds of people showing up before we were done.”

Francona saw the same competitiveness on the ball field, even if Jordan did not understand the protocols of the game. Early in the season, he stole third base while the Barons held a big lead. The opponents began cursing and yelling for what in baseball is seen as rubbing it in.

“Their whole dugout was screaming at me,” Francona says.

Francona had to explain to Jordan that when you have a big lead in baseball you play much less aggressively. Jordan shrugged his shoulders.

“In the NBA,” he said, “when they give you a layup, you take it.”

Says Francona, “But that was early on. By the time he got done he knew all that stuff.

“I thought it was phenomenal what he did, because of what he already had accomplished in basketball and suddenly to be thrust into a Double A setting. By the time he was in the fall league he was so much better. He wanted to know everything—when to run, when not to run. … He asked so many questions that he was learning at a rapid pace.”

As the year progressed under Barons hitting coach Mike Barnett, Jordan began to learn the basics of hitting, and how to use his long arms and 6'6" frame in more efficient movements. Jordan was strong, but because he struggled to sync the timing of his kinetic movements his swing relied too much on his arms and not enough on his body. Swinging too much with the arms robs a hitter of power. But that Jordan drove in 51 runs despite the lowest slugging percentage in the White Sox system (.266) proved that Jordan’s ability to rise to the big occasions on the court translated to the ball field.

“When the game was on the line, that’s who he was,” Francona says. “In batting practice he could not get a bunt down. Could not do it. Listen, I never want to embarrass any player, but there are some situations in a game that call for certain plays. I’d give him the bunt sign and he would lay down a perfect blueprint of a bunt. I mean, perfect. I’d go, ‘You’ve got to be [kidding] me!’ And then the next day in BP? He couldn’t get a bunt down to save his life.

“One night, he didn’t play in a game in Jacksonville. Now it’s late in the game, it’s close, and I send him in to pinch hit. He didn’t come through this time—he made an out—but after the game he comes up to me with this big smile and says, ‘Thanks, man. That was so awesome.’ He’s thanking me because he loves to be in those moments with the game on the line.”

Jordan wound up with a slash line at Birmingham of .202/.289/.266, which is similar to what Billy Hamilton put up in the majors last season as a reserve outfielder (.218/.289/.275). Hamilton is a game-changing base runner and defender. Jordan was no Hamilton in that regard, but only two players in the White Sox system that year attempted more stolen bases. He was progressing enough as a fast runner, defender and hitter to believe he could fill a reserve role, especially under expanded roster rules in September.

Any chance of a September promotion in 1994 evaporated when the major league players went on strike Aug. 12.

At the end of the Arizona Fall League I asked Dick Egan, a scout for the Marlins who was there, to assess Jordan’s chances to become a big leaguer.

“My opinion is, he’s a guy you have to follow,” Egan said. “Time is going to run out on him, but it would be neat if he made it. I’m not betting against that s.o.b. The chances are slim, but the upside is extraordinary.”

Insufficient skills did not stop Michael Jordan’s baseball career. The strike did.

Spring training in 1995 opened without the major league players. Jordan was ticketed for Triple A Nashville. He bought a membership at a golf club there in anticipation of his assignment. As the strike lingered, owners began making arrangements to start the season with replacement players. Reinsdorf and Schueler never had any intention of asking Jordan to be one of them. They knew there was no chance of Jordan reaching the big leagues by crossing a picket line.

“I won’t be there,” Jordan said during the AFL season. “I know the impact that I have.”

As camps opened, a key question needed to be answered: When is a player defined as a replacement player? Opening Day? Day One of spring training? Union chief Donald Fehr said any player participating in spring training games in which admission is charged would be considered a replacement player. The White Sox pushed their minor leaguers to decide whether they would play in those games. Those who opted out either would be sent home or assigned to the smaller minor league clubhouse at the training complex. Those who opted out also would no longer be permitted to park in the players’ secured parking lot; they would have to find parking on the street and walk to the complex.

On March 2, Jordan, without a parking spot and with no intention of being a replacement player, left camp—and left baseball for good. He soon returned to Chicago and began secret workouts with the Bulls. He officially announced his comeback March 18.

Michael Jordan spent 13 months as a professional baseball player. He was the best thing to happen to baseball at the time, even if many in the sport refused to see it.

“Fast forward to 2016,” Alderson says, “and now you have Tim Tebow. We really haven’t come that far.”

Tebow’s football options had closed when he turned to baseball. Jordan was still at the top of his basketball game. So I asked Alderson if baseball might be more welcoming to LeBron James today than it was for Jordan in 1994.

“Yes,” he says, “in part because baseball is a more complex industry than it was 25 years ago and it’s far more business-oriented. People would look at a LeBron James dalliance with baseball from a business perspective.”

Twenty-six years later, it’s worth remembering the basic fact of what Jordan did for baseball. One of the greatest athletes and most famous persons on the planet chose baseball—and more specifically, he chose minor league baseball. Jordan wanted to earn his way into a big league uniform, not to have it handed to him. It was an incredible affirmation for the sport, especially because underneath it was the bond between a father and a son, which continued beyond the grave of James Raymond Jordan Sr.

Three years after leaving baseball, in his book For the Love of the Game: My Story, written with Mark Vancil, Jordan reflected on those 13 months in baseball. He wrote:

“How would I describe my baseball experience? I would describe it now the same way I described it then. Every moment was a warm one. I remember looking up in the sky from time to time and being amazed at how much my life had changed. I had no fear. Just a warm feeling. I can’t describe the sense exactly, but now it seems like I was living a dream.”

What better endorsement of baseball ever was crafted by a .202 hitter?