Minor League Baseball Is in Crisis

Jeff Savage first learned about COVID-19 in February, reading an email from a distributor of novelty rings in China. The note was confusing at first for the president of the Sacramento River Cats, the Triple A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants. It said the business had to temporarily close its warehouse to stop the spread of something called the novel coronavirus, which was sweeping across China, killing thousands of people and infecting tens of thousands more. Because of the shutdown, the email continued, the Triple A champions would not receive their 5,000 faux-platinum rings in time to give them to fans attending the April 14 home opener.

The news was distressing, but not in the ways that would become obvious just a few weeks later. At the time the message reached Savage’s inbox, the U.S. was still weeks from the lockdowns, sicknesses, large-scale fatalities and epic economic destruction that would ravage the nation.

Sitting in his office, Savage, 42, says his old concerns feel quaint—as though from a different reality. Like many other family businesses, his is under siege. Following professional baseball’s shutdown in March, minor league clubs now exist in a sort of sports purgatory, 160 affiliates unsure whether they will have games to host and worried about how they will pay employees, settle debts, and potentially return millions of dollars in ticket and advertising revenue to fans and sponsors. Not to mention the existential anxiety they’ve felt since early last winter, when Major League Baseball proposed a plan that would reportedly eliminate 42 affiliates and give big league clubs greater control over the system.

“It’s like this big wave is about to hit us,” Savage says. “Everything is on fire.”

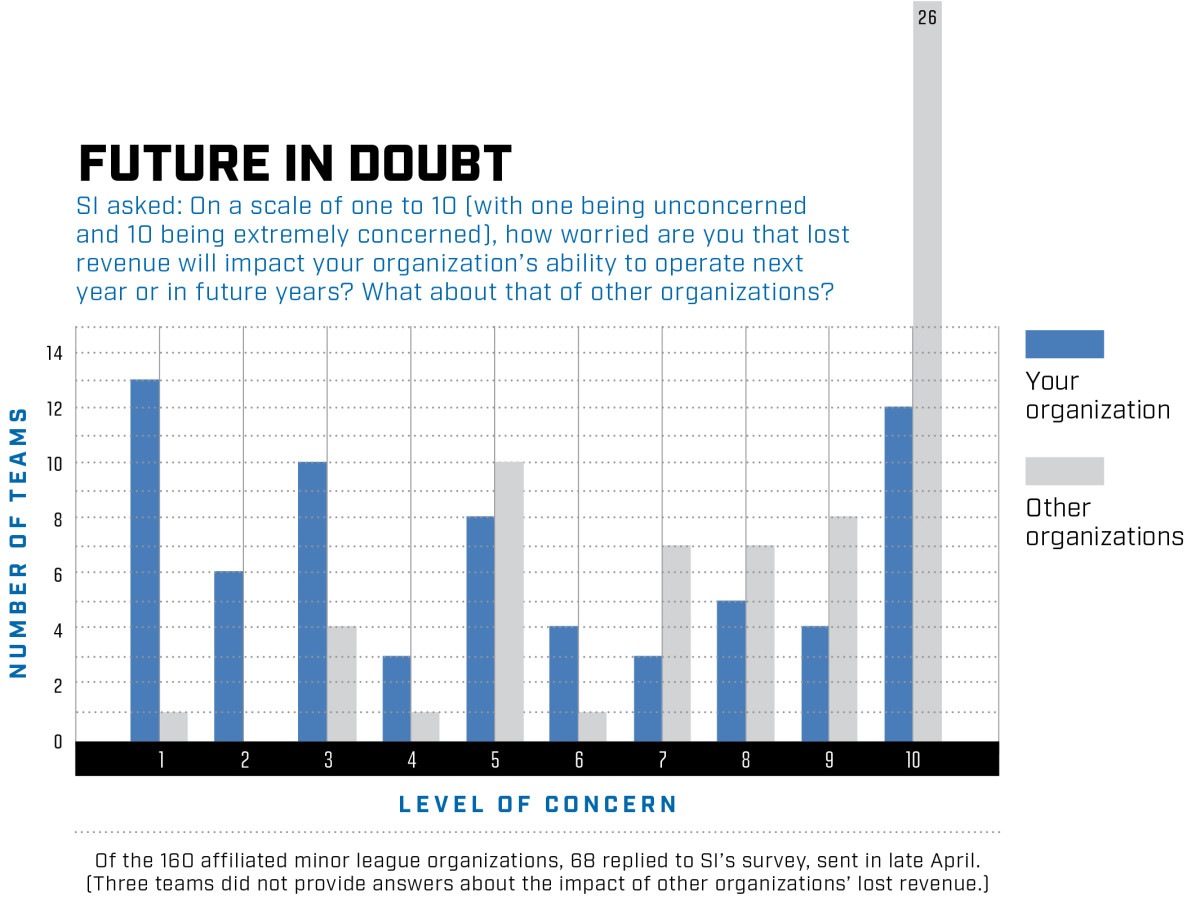

A Sports Illustrated survey of minor league organizations, sent to all teams in late April, shows just how desperate the situation has become. The responses of 68 clubs—in addition to interviews with executives representing 21 of those teams—make clear that the minor leagues are facing a crisis that could destroy professional baseball in cities across the country. At every classification level, in markets ranging from metropolitan cities to rural outposts, front offices are worried about their clubs’ survival, concerned about the viability of rival teams and wondering how the minors will recover from a pandemic that is pummeling an American institution.

Twenty-four teams (or 35% of respondents) said they were seriously concerned that lost revenue from this season would impact their ability to operate next season or in future years, ranking their level of worry at seven out of 10 or higher. Twelve of the clubs—including two of the 16 Triple A teams that replied and five of the 13 from Double A—said they were “extremely concerned” about their ability to continue operating in the future: a 10 out of 10.

Teams were even more bearish about their fellow organizations’ prospects: 48 teams (74% of respondents) thought lost revenue would significantly impact other clubs’ abilities to operate in the future, answering with a seven or higher. Of those teams, 26 put their concern at a 10.

Many clubs have already felt significant pain: Half of the respondents to the survey, which promised anonymity, indicated they have laid off or furloughed staff—in some cases leaving a single person to handle day-to-day operations. Several teams have plans to gut their front offices should minor league seasons get canceled—which more than half of responding teams said they expected to happen. Even an eventual MLB return with no fans, as has been floated by league officials, would not guarantee the return of the minors.

Fifty-five of the responding teams (81%) said they received small business loans through the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program. Considering that smaller and less-connected businesses have had trouble securing PPP money, that’s an extraordinary level of success. Just four teams reported their PPP requests were denied; another team said it missed the deadline and hoped to apply later. Still, minor league executives said the eight-week cash infusion was only a stopgap that would have a negligible impact if entire seasons are lost.

Even as taxpayers help to keep teams afloat, several minor league affiliates reported that their MLB teams seem unconcerned about their plight during the COVID-19 crisis. Though MLB clubs are not allowed, by rule, to directly pump funds into their affiliates, several minor league executives chafed at not having received so much as a check-in phone call.

The frostiness comes amid months of tense back-and-forth between MLB and the minors over the Professional Baseball Agreement, which governs their relationship. Last extended in 2011, the deal expires this September and, as part of the negotiations, MLB is seeking to save costs by eliminating more than a quarter of affiliated teams by next season while pushing for other significant changes to its minor league partnership.

For those organizations that survive the massive restructuring, minor league executives said, congressional action might be needed to keep teams alive beyond the pandemic. Without extensive financial help, they added, clubs might be forced to shut down or declare for bankruptcy protection. Teams that have served for decades as community bedrocks—while providing an affordable way to have a night out at the ballpark—could disappear in an instant.

“If anyone is telling you they’re not concerned about their survival, then that organization is lying,” says David Lozinak, the chief operating officer for the Altoona (Pa.) Curve, the Double A Pirates affiliate. “No one has the extra $2 million, $3 million, $4 million in their bank account.”

In Sacramento, Savage laid off 30 of his team’s 65 full-time workers in late April and has to find a way to continue paying off the bonds that built a $46 million, privately owned stadium in 2000. “We’re in an agonizing position,” he says.

The River Cats have three Triple A championships and five Pacific Coast League titles in their 21-year existence, and recently inked a naming-rights deal for their 14,680-seat stadium, prompting a series of offseason expenditures that included everything from new ballpark signage to revamped suites to replacing the polo shirts that ushers wear at games. In what should have been the first full month of minor league games, Savage, in addition to the layoffs, had to cut salaries and tell another 500 seasonal workers they might not have jobs this year.

“You can’t sleep at night, knowing some of the things you’ll have to do to survive,” he says. “It’s sort of unthinkable that we’re in this position.”

***

Across the country minor league ballparks should be buzzing. Fans should be filling stadiums in Lansing, Mich., and in North Little Rock, Ark., families happily chomping away in their seats on $2 hot dogs, dancing in the aisles with mascots like Chico, the El Paso Chihuahua, and laughing when their neighbor wins the dirtiest-car-in-the-parking-lot contest.

On a Friday evening in early May, the scene at the Colorado Springs stadium of the Rocky Mountain Vibes was decidedly different. Jennifer Cupples; her husband, Ken; and their two children pulled up curbside to pick up a food order. The family had been player hosts last year for the Vibes, the Brewers’ short-season rookie league team that is reportedly on the list of teams slated for contraction. Every year thousands of families nationwide house young ballplayers, often from other countries, baseball’s own form of cultural exchange. As Toasty—the Vibes’ anthropomorphic flaming s’more mascot—stood near the Cupples’ Toyota SUV, a Vibes employee handed Jennifer her $35 “Quarantined Couple” meal, which included chicken bacon ranch and pulled pork sandwiches, fries, cookies, a bottle of wine and two rolls of toilet paper. The Cupples hoped this wasn’t their last visit to the ballpark.

“This place has become part of our family,” Jennifer says.

Toasty’s Takeout, as it is called, is the brainchild of Vibes general manager Chris Phillips, an 18-year veteran of minor league front offices. The curbside food business runs three evenings per week at the stadium, and a good night might earn $600—“Hardly a get-rich-quick scheme,” Phillips says—but it’s enough to keep some of the staff employed through the pandemic. “We can either sit around and feel bad about this situation, or we can have some fun,” Phillips says. “We’re going to focus on 2020, hope for the best and then deal with what happens after that.”

Plenty of other teams have gotten creative. The Triple A Storm Chasers, for instance, launch fireworks for Omaha’s residents that were initially marked for special game nights—if nothing else, a decent bit of marketing. But other problems can’t be fixed: At Durham Bulls Athletic Park, in North Carolina, cardboard boxes filled with promotional T-shirts, hats and Bulls-emblazoned coolers line the concrete concourse. And in Fort Wayne, Ind., $2 million in facility upgrades to the Class A TinCaps’ Parkview Field may well go unused this year, but that doesn’t mean the bills won’t come due.

“By the time we get past [COVID-19], we might be looking at 18 months without significant revenue,” says Jason Freier, the chairman and chief executive for Hardball Capital, which owns the TinCaps, a Padres affiliate, as well as the Class A Columbia (S.C.) Fireflies and the Double A Chattanooga Lookouts. “Minor league baseball is in a terrible position, because we can’t just open up and start playing if we get the all-clear in November. We have to sit and wait, and I don’t know of many businesses that can go that long without income.”

In many ways the game played in Fort Wayne or Idaho Falls looks like the one in Fenway or Wrigley, but major and minor league baseball are vastly different enterprises with far different goals (and price points). For years, the money-making side of the minors has been less about the on-field play than the entertainment in the stands, a bankable commodity that has seen the rise of funky and marketable team concepts like the Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp and the Rocket City (aka Madison, Alabama) Trash Pandas, Star Wars–themed jerseys, and hats emblazoned with tacos, flying chanclas and steamed cheeseburgers.

“Minor league teams are part of the community in ways that much larger pro sports franchises can’t be,” Phillips says. “When you’re at this level, it’s about how you’re making connections with every person in that stadium on that night. We aren’t stuffy because we can’t afford to be. Fans will leave the game and probably won’t remember the score, but they’ll always remember if they had fun.”

Often, those community ties have been generations in the making. The Buffalo Bisons were founded in 1877, the Chattanooga Lookouts in 1885 and the Toledo Mud Hens in 1896. The Altoona Curve started play only in 1999 but quickly became interwoven with their central Pennsylvania hometown: The team books nonprofit groups to help run concession stands at every home game and lets them keep a percentage of sales—helping raise money for everything from high school softball to youth outreach programs. “Every minor league team is a lynchpin to their communities,” says Lozinak, the Curve’s COO. “This isn’t just a baseball game for these families who come here, this is a getaway, a gathering space.”

That formula has proved to be a big financial success: Attendance across the minors topped 41.5 million in 2019, an increase of more than one million fans from the season before and the 15th straight year above 40 million. The Dayton (Ohio) Dragons, for example, are perennial attendance leaders at the Class A level, and saw their value rise to $45 million, according to Forbes in 2016, joining Triple A franchises like the River Cats and Charlotte Knights as the highest-value teams in MiLB. (By comparison, Forbes estimates the average MLB club is worth $1.85 billion.)

But everything that makes minor league ball special to tens of millions of fans each year has also made it exceptionally vulnerable during the pandemic. Social distancing doesn’t fit well with an industry that depends entirely on rear ends in seats. “Minor league teams don’t have the lucrative television contracts or the massive merchandise sales that major league teams enjoy,” says John Allgood, the former executive director for the Triple A Oklahoma City RedHawks who is an assistant professor in Temple University’s sport, tourism and hospitality management department. “Most teams are getting 70 games, over five months, to make every dollar that will carry them through the rest of the year. Every day with coronavirus shutdowns is one more day a team can’t make money. If no one is in the stands, 100% of that revenue has walked out the door.”

In other words, major league teams can play in empty stadiums this year because local TV contracts and three national deals (accounting for $1.7 billion in annual revenue, split among 30 teams) will soften the economic blow. By contrast, in response to SI’s survey, most teams said a canceled season would result in a 95% to 100% loss in annual revenue. Part of what ties minor league franchises so deeply to their communities is that they are supported, almost exclusively, by a few thousand fans each night, plus advertising bought by local restaurants and bars, the neighborhood orthodontist and the town pest-control company.

And in the era of COVID-19, everyone is hurting. Local businesses failing, or even cutting their advertising budgets, is a looming disaster for clubs. “Of course I’m worried about our team, but I’m worried about our businesses and all the people in our community who are being affected by this,” says Marcus Sabata, the general manager for the Double A Jackson (Tenn.) Generals. “We’re a small business, too, so we get it. We’re right there with them.”

While MLB has yet to announce whether minor league games will be played this year, the specter of a canceled season looms large within front offices across the country. Season tickets were sold in the offseason, as were sponsorships, and those companies’ names now dot walls in empty ballparks and are stamped on boxed-up bobbleheads.

“All the deposits have come in, and we’ve spent them,” says one owner, who requested anonymity to speak candidly about the situation facing minor league teams. He adds that he worries about a Great Depression–like rush among sponsors if the season is canceled. The local auto dealer that paid for a promotional night that never happened, for instance, may well want its cash returned. “They might need that money back to get them through,” the owner said. “Imagine if every sponsor wants that money. We’re facing an economic crisis.”

Even the best circumstance—keeping the money now and rolling over season-ticket purchases and sponsorships to next year—means teams could be operating with steep losses beyond just this season. “After [the pandemic] passes, that’s still not the end,” says another owner. “We’re going to see bankruptcies, team closures. Some owners will be forced to sell, to just give up. That absolutely will happen, and sooner, rather than later.”

***

On a sunny April day, in what should have been the Southern League’s first month of games, Sabata stood in the third-base stands at the Ballpark at Jackson and tried to figure out how he could spread 500 season-ticket holders across a 6,000-seat stadium while maintaining a proper six-foot distance between families. There was no easy way to make it work. Some people who had been going to games for years would lose their beloved positions behind the dugout. Some might have to move to another part of the stadium. “It’s like a big jigsaw puzzle,” Sabata says.

Papers were piling up on his desk. Sabata was spending his afternoons running numbers on sneeze guards for concession stands and plastic covers for cash registers. There was a Zoom meeting with his fellow Southern League GMs, all of whom were tired and overwhelmed and worried. “I’m a realist,” says Sabata, who is in his third season with the club and his first running team operations. “But I’m trying to find a way to be optimistic. We’re putting together contingencies, but this sometimes feels impossible. We’re stuck in the mud, waiting to see what MLB is going to do [about this season].”

Even if minor league ball were played this year, Jackson’s future is uncertain. This past winter, Baseball America released a report listing 42 teams that could lose their major league affiliations in 2021. Those included the entire short-season Pioneer League, which first played in 1911, the rookie-level Appalachian League, and teams throughout A and Double A ball. Among the Double A teams was the Jackson Generals.

While the 42-team list has not been formalized, MLB officials have said contraction is a necessary step that will help big league franchises better manage prospects, reduce travel costs and ensure their players have adequate facilities to help them develop. MLB has framed its push as a way to modernize the system while making improvements to player pay and working conditions. If the minor leagues developed as a crazy quilt patchwork of (often colorful) owners striking affiliate deals with big league clubs, the new major league vision seeks to snap a vertical org chart into place.

As part of its plan, MLB wants to exert more control over the minors, perhaps by selecting affiliates to place them closer to big league clubs, moving certain teams up or down within classifications and leagues, eliminating individual leagues’ offices and reducing the role of minor league baseball’s headquarters in St. Petersburg, Fla. There also has existed the possibility of a nuclear option, that MLB could simply end its relationship with minor league baseball and set up its own developmental system.

MLB’s contraction plan created a firestorm of negative publicity last winter, prompting a bipartisan political coalition that called for MLB to preserve its affiliations. Senator Bernie Sanders, in a letter to MLB commissioner Rob Manfred last year, wrote that the elimination of minor league clubs—including possibly his hometown Vermont Lake Monsters, in Burlington—would be “an absolute disaster for baseball fans, workers and communities throughout the country.”

As part of the reported plan, MLB could turn some of the contracted clubs into summer wood-bat teams for college players—much like the popular Cape Cod League—and then make some others part of what has been called the “Dream League,” a series of independent teams that are fielded with players recently cut from MLB organizations. Minor league teams have argued that the loss of their major league affiliations would destroy their investments.

The lack of communication about contraction and other potential organizational changes, several minor league executives said, has only been exacerbated by the onset of the pandemic. And as the clock winds down on the current PBA, their collective hand is now weaker than ever: It’s not hard to imagine that financially depleted teams will be less unified, with clubs now far more concerned about their own survival. MLB can also now more earnestly argue that clubs being more geographically contiguous—leading potentially to lower travel costs—is even more imperative to newly cash-strapped affiliates. And then there’s always this: Without a deal, there won’t be a provision for MLB to supply players to minor league teams in 2021. “Major League Baseball has all the leverage,” one minor league owner says.

“We’ve got no cards to play,” says another executive. “But if Major League Baseball suddenly wants to blame the coronavirus for this situation, I’ll call bulls--- on that.”

In a statement to SI, an MLB spokesman said the league is committed to “good faith negotiations,” adding, “Major League Baseball looks forward to continuing our discussions with Minor League Baseball about how we can jointly modernize player development and continue to have baseball in every community where it is currently being played—MLB’s goals since the beginning of our talks.”

While MLB and MiLB issued a joint statement in April, describing “constructive” PBA negotiations that would lead to a “long-term agreement in the near future,” sources say the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic could push a deal until later this summer. The timing hardly gives minor league clubs clarity, making it even more likely that the one-two punch of a new PBA and the pandemic will permanently alter the minor league landscape.

“Minor league baseball as we know it is no longer going to exist,” says Jordan Kobritz, a professor of sport management and sport law at SUNY-Cortland who has investments in the Triple A Wichita Wind Surge and the Class A Charlotte (Fla.) Stone Crabs. “Coronavirus basically undermined everything minor league baseball could have done to fight this.”

Asked whether the minors had requested a postponement of contraction, should seasons get canceled, a spokesman for MiLB said MLB was not considering the option. In Jackson, that could mean the countdown has begun to eliminate the franchise. “It’s really disappointing,” says Sabata. Without a season, the team might not even get a chance to say goodbye to its fans.

“I’m not even thinking about that right now,” Sabata says. “I just can’t.”

***

Phillips, the Vibes’ GM, and his 15-member front office have been brainstorming ways to drum up additional income. There are currently five high school graduations scheduled at the stadium (plenty of room for social distancing), as well as plans to honor senior softball and baseball players on-field throughout the summer. The team is also working with Colorado Springs to potentially host its Fourth of July fireworks show. And plans are moving ahead to hold a series of movie nights, where families could park on the field. The idea, Phillips admits, would have freaked out the team’s grounds crew just a month earlier.

“This is bittersweet, but we’re still showing we want to be part of this community,” says Chris Evans, the team’s catering chief, who was also in charge of procuring toilet paper for that Quarantined Couple menu item—a job that sent him to grocery stores, pharmacies and big box retailers across the city.

Outside the stadium, Jennifer and Ken Cupples unboxed their meals while their six-year-old daughter, Hope, threw a baseball in the air. Several friends arrived a while later—families who’d also hosted Vibes players last season. The husbands and wives set up chairs or stood several feet apart from one another, talking about the pandemic, the potentially lost season, and whether minor league baseball would exist in Colorado Springs come next year.

They laughed about player sleepovers at their homes, about the Dominican kids who’d never tasted a s’more before arriving in the Springs, about birthday parties and the time they drove five hours to Grand Junction, Colo., where they surprised their players and waved at them from the stands. They talked about their final Sunday with the players last season, how they cried all the way home from the airport, how each of the young men had stayed in touch during the pandemic.

The group got quiet as their food began to arrive. Toasty, the s’more, stood off to one side, hanging on to the sides of his cloth graham crackers. “Those boys were just like our kids,” one of the women finally said. The group nodded. “Baseball is special to all of us. I just hope this isn’t the end.”