Inside the Chaos of 1981—MLB's Last Severely Shortened Season

World wars, earthquakes, civil unrest, terrorist attacks, military threats, infectious mosquitos, strikes and lockouts. Life has disrupted many a baseball season and the comfort provided by its constancy of games. But never like this. The coronavirus pandemic is likely to reduce the 2020 season to the shortest one since the American League joined the National League in 1901—if there is any season at all.

Rob Manfred continues to consult government and public health officials to find a path forward for baseball this season. The league has proposed safety protocols to the players association and continues to negotiate financial terms that would allow a 2020 season to commence. Yet playing remains only a hope. We’ve already seen the first April without a major league game in 137 years, since the American Association opened as scheduled May 1, 1883.

If baseball does return, what might it look like? The answer may be found in the shortest season this one threatens to eclipse: 1981. Players went on strike June 12 to protest a demand by owners for a compensation system to accommodate teams that lost a free agent. They didn’t play another game until Aug. 9. That ripped 59 days from the baseball calendar, never to be restored.

As in ’81, we again could be looking at compressed training camps, schedule inequities and a redesigned postseason format. Unlike 39 years ago, when the shutdown resulted from baseball’s own doing, a resumption this year should be met by fans with relief rather than animosity.

The story of 1981—baseball’s latest return and shortest season—is a story of organized chaos. It is the story of eight-day training camps, wildly unpopular wild cards, renewed hope and Bob Hope, 10,000 whistles and $10,000, an exotic dancer on the pitching mound, and, as a television draw and a public trust, the end of baseball as we knew it.

No one better personified this nutty, ad hoc window into baseball history than a 40-year-old first baseman for the Phillies who was one of the country’s most famous and most polarizing figures. The return of baseball in 1981 was just as messy as Peter Edward Rose or, as third baseman Mike Schmidt called his teammate that year, “the most likable arrogant man I’ve ever met.”

***

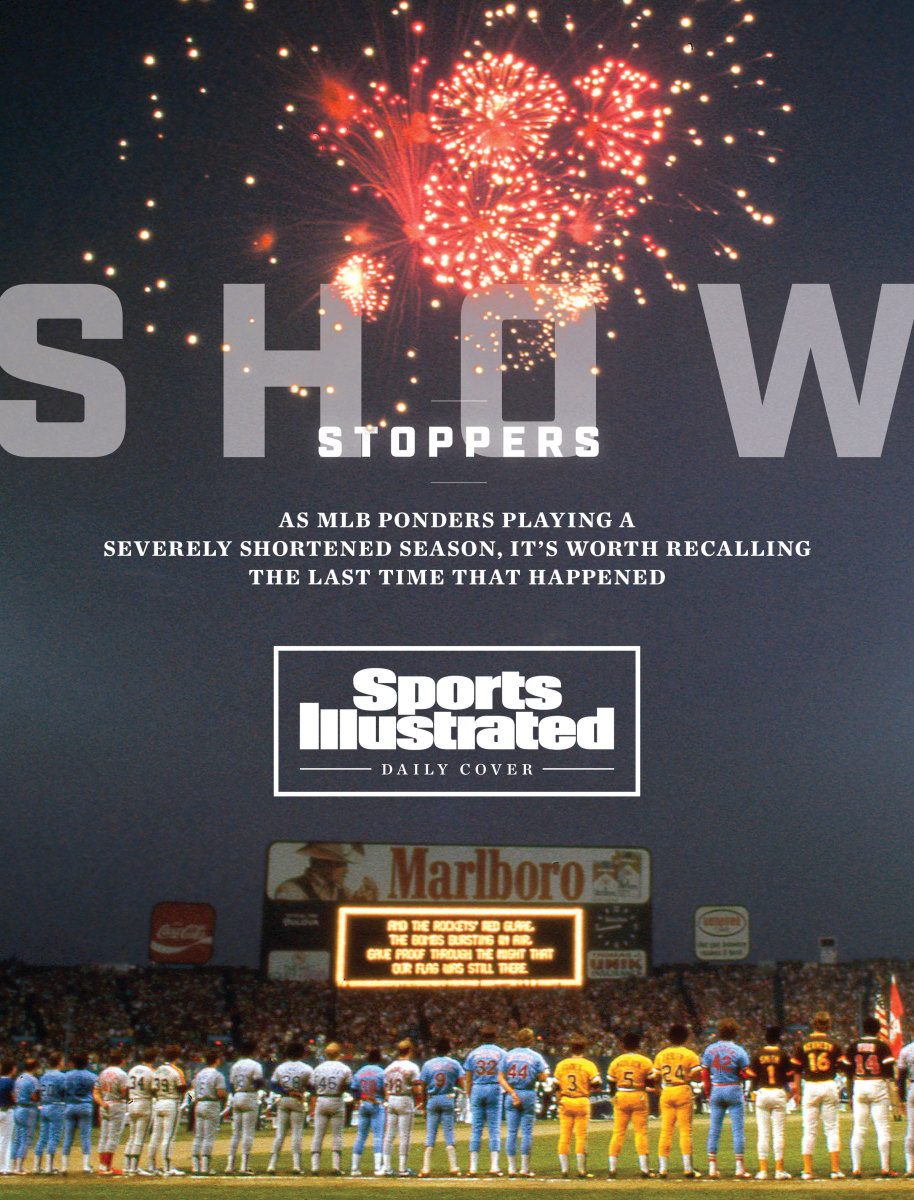

After reaching an agreement players had just eight days of training before the first matchup: the All-Star Game in Cleveland on Aug. 9. The man entrusted with reintroducing baseball to the viewing public was a bit nervous. NBC coordinating producer Mike Weisman had old pros Joe Garagiola and Tony Kubek in the booth and Bryant Gumbel—then 32 and just five months away from cohosting the Today show—as a field reporter. But Weisman knew his bosses expected more than 60 million people to tune in, which would break a viewership record from the previous year. He called the game “the most significant in the past 20 years.”

“It might even be the most important All-Star Game ever,” Weisman added. “It has the potential for the biggest audience in history. If it’s a good game and we do a good job, it will be a tremendous boon to baseball. If it’s a bad game or we do a lousy telecast, the negative impact could last the rest of the season.”

With so much uncertainty, savvy reporters in town for the game knew where to go for a surefire quote: Pete Rose’s locker.

On June 10, the last Phillies game before the strike, Rose had slapped a single off Nolan Ryan, tying Stan Musial for the most hits in NL history. Ryan then struck out Rose three straight times, leaving him stuck on 3,630 hits for the next 59 days.

Like or loathe him, with room for almost nothing in between, Rose made sure you watched him. He played baseball with a prickly obsessiveness, treating each game as if he had just learned it would be his last. Every night he drained the reservoir of his will like oil from an engine, only to repeat such siphoning the next night, and the night after that. He sprinted to first on walks, dived headfirst into bases, spiked the baseball after catching the last out of an inning at first base and bounced like a bantam when he walked or ran.

Reporters loved Rose because he was a great player and he knew it. He could recite his stats the way people did their phone numbers. He filled notebooks as well as he did box scores. He loved the limelight. He was a pitchman for aftershave, hair dye, health insurance, sporting goods and Japanese noodles.

Rose attacked the strike-induced hiatus with the same vigor he did ball games. He played five sets of tennis two or three times a week with his agent, Reuven Katz, at the Eastern Hills courts in Cincinnati. At 4:45 every afternoon—because that’s the time he would have been arriving at a ballpark—he stepped in against one of the pitching machines at a place called Ball Game and set the speed to 70 mph. (The kids in the cages around him, swollen with the insouciance of youth and the need to prove something, would pick the 90 mph setting, the only other option.) Rose proceeded to take 250 cuts, grooving his swing like depressions on a vinyl album. He did this every day and struck a deal with Ball Game’s owner, signing autographs in lieu of feeding quarters into the Iron Mike.

Rose hit so much because he wanted to make sure the callouses on his hands never softened. There was something else: Rose, forever the rolling stone, feared the catastrophe of stopping. Musial wasn’t the goal. He wanted nothing more than his 4,192nd hit to pass Ty Cobb as the all-time leader.

In Cleveland, Rose did not disappoint the writers, starved as they were after a forced 59-day diet without quips, quotes, gossip, chatter and the postgame cocktail or two.

“Pete, did the strike hurt you?”

“Phone bills were cut in half,” Rose said. “I must call Sports Phone 15 times a day to get scores. No games meant no scores meant no calls. I got the world market cornered on dimes back home.”

Reporters found it funny. Before sports radio and the internet, Sports Phone was a telephone service that provided callers with continually updated recordings of scores. It was at its peak in 1981. Its core clientele was degenerate gamblers—or people who call 15 times a day from a pay phone. Eight years later MLB would ban Rose for life for betting on baseball. But on that night in 1981, Rose and baseball were as inseparable as ever.

On his lineup card for the NL All-Stars, Phillies manager Dallas Green had Dodgers second baseman Davey Lopes batting leadoff with Rose behind him. Rose saw that and made a beeline for Green. “Who would the fans rather see as the first batter after a seven-week strike?” Rose asked Green. “A guy hitting in the .100s or a guy who will break Stan Musial’s record with his next hit?”

So Green wrote a new lineup with Rose atop it. He would be the first batter in the first game of the second coming.

***

Baseball had suffered work stoppages in 1972, ’73, ’76 and ’80—three of them confined to spring training—but they were brushfires doused in eight to 17 days. An inferno broke out in 1981.

Owners wanted to reclaim ground they had lost with the advent of free agency in 1975. Players thought owners were trying to break their union. The headline on the June 22 cover of Sports Illustrated agreed: strike! the walkout the owners provoked.

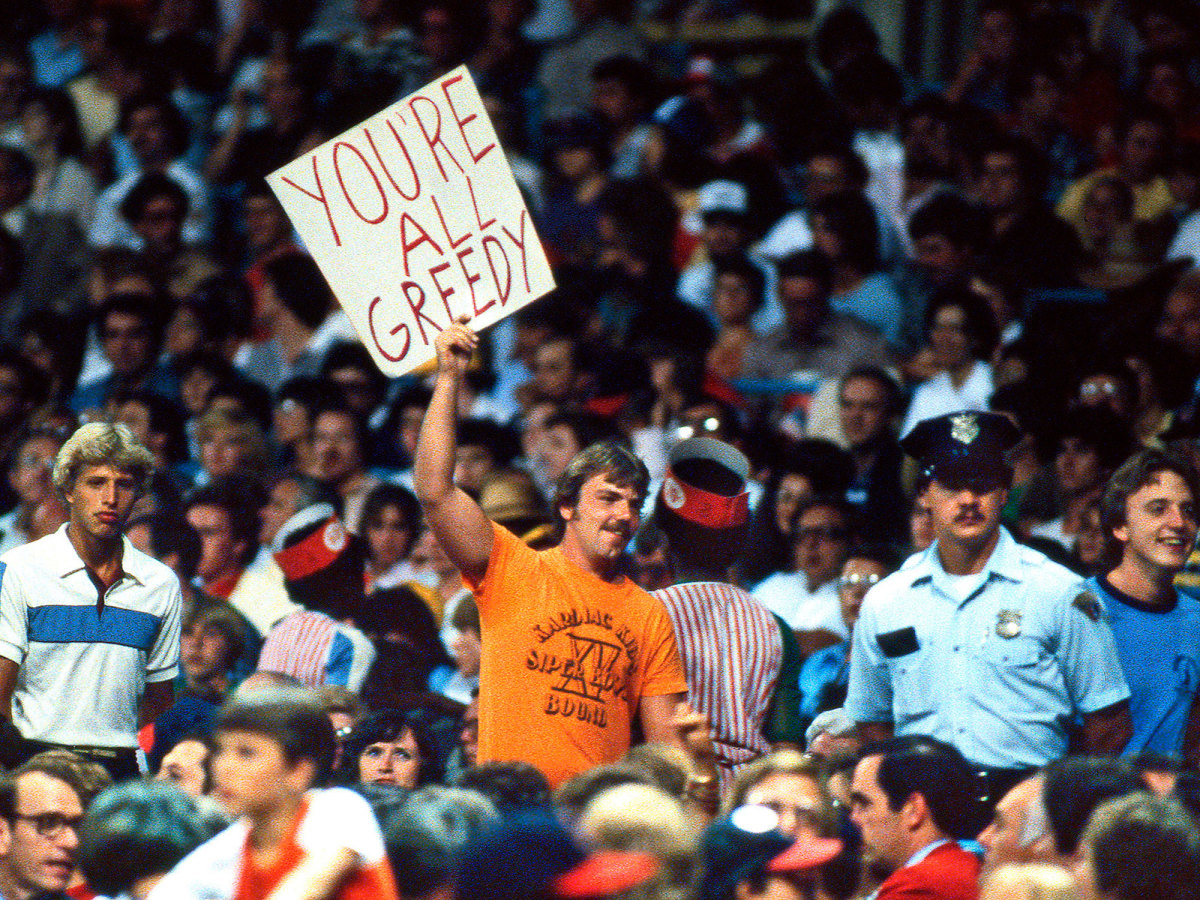

Fan reaction was split. Respondents to a New York Times–CBS News poll in July were evenly divided on whether the owners or players were right, though even greater numbers had no opinion or didn’t care.

The owners settled with the players in the early morning of July 31, just as their strike insurance ran out. Yet trust was lacking even upon agreement. The lead negotiators, Ray Grebey for the owners and Marvin Miller for the players, refused to pose together at the news conference in New York City.

In a last-minute deal, owners granted players service time for the days they were on strike. In return players agreed to extend the collective bargaining agreement by one year. So eager were the two sides to salvage what was left of the season that they agreed to play the All-Star Game in just nine days, with the regular-season schedule resuming the next night.

Angels manager Gene Mauch and Orioles general manager Hank Peters were among the old baseball souls who argued for expanded rosters to ward against arm injuries from pitchers throwing in games so soon. No such accommodations were made, other than allowing a 30-man roster and a reentry rule—permitting players taken out of games to return later—only for each team’s two exhibition games. The season would restart with the usual 25-man rosters and substitution rules.

Pitchers came back to work in various states of arm health. Some continued to throw during the strike, some didn’t. Phillies righthander Marty Bystrom, a second-year player with a new house, new car and no income, took a job as a car salesman during the strike. He said it left no time for physical conditioning. He did no throwing.

When Bystrom showed up at the Vet out of shape, Philadelphia shipped him to Double A. Green was dumbfounded how “a young guy would let himself go like that.”

In Cleveland, after watching Bert Blyleven throw for 20 minutes, Indians manager Dave Garcia said, “Blyleven’s been working out several days a week, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see him go nine innings his first time out.” (Blyleven, 30, threw nine innings in his first start after the strike, facing 35 batters and giving up nine hits.)

The “training camps” were typically morning workouts and afternoon simulated games. Some teams had to find other fields because their home ballparks had been booked for events to help owners recover lost income. The Mariners relocated to the University of Washington and Bellevue Community College, the Angels to Fullerton Junior College and the Reds, who had rented Riverfront Stadium to a jazz festival, to the University of Michigan.

Most clubs played home-and-home exhibition games. The Cubs and White Sox went nine innings without either team scoring, convincing Sox manager Tony La Russa that he was right when after one day of workouts he decided the pitchers would be ahead of hitters. “Pitchers have only one skill to maintain, while players have to hit, run and throw,” he reasoned.

A’s manager Billy Martin let righty Steve McCatty throw a 10-inning complete game in his first start in two months; he delivered 148 pitches. “McCatty,” Martin said, “was the guy who showed me after the layoff he worked harder, pitched more often than the other guys.”

McCatty, 27, threw complete games in five of his first six starts after sitting for two months. The next year, while pitching with tears in his eyes, his shoulder hurt so badly “it felt like my arm was going to come right out of the socket,” he told SI in 1984. Never again was he the same pitcher.

***

NBC's Weisman had previously miked coaches Lou Holtz and Bobby Bowden during the Orange Bowl, but he promised no gimmicks for the All-Star Game. “People just want to watch baseball,” he said.

Forty percent of his crew was on vacation, so Weisman and director Harry Coyle cobbled together replacements. Somebody asked Coyle about the difficulty of putting on a broadcast with so many new people.

Coyle harrumphed, “I’ll give them about one out to get going.”

Rose took the first pitch from Tigers ace Jack Morris for a ball. Suddenly a high-pitched shrill echoed across the cavernous stadium. Confused, Rose turned to home plate umpire Bill Haller. “What’s that?” he asked. It was the sound of 10,000 whistles. A Washington, D.C., bartender handed them out as a way for fans to express their anger and frustration over the strike. They blew a piercing protest upon the first pitch of every half-inning.

On a 2–0 pitch, Rose flicked a nasty down-and-away sinker from Morris into left field for a single, making it look like a 70 mph pitch from the machine at Ball Game. The grooves in his swing hadn’t changed a bit. “Look at that!” Kubek gushed on air. “That man is unbelievable.”

His second time up, in the third, Rose grounded out against Indians righty Len Barker. As Barker bent at the waist to get the sign for his next pitch, suddenly he straightened up, distracted by a sight in the corner of his eye. Bounding toward him was Morganna, an exotic dancer with a 60-inch bust. Known as the Kissing Bandit, she would interrupt games to buss the cheeks of ballplayers. She grabbed Barker around his neck, pulled him close and gave him a peck. Weisman showed it all.

In a box by the first base dugout, commissioner Bowie Kuhn had his first good laugh in months. So did his seatmates: Bob Hope to his right and Vice President George Bush to his left.

Morganna bounced off the field, accompanied by two uniformed police officers who held her daintily by each wrist. The Kissing Bandit had struck again in a career of stolen smooches that dated to 1969. Born in Louisville, she made her debut at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. Her first target: Pete Rose, of course.

***

Weisman’s crew put on a good show. He had judged his audience’s mood well. A review by the Associated Press found it “clean and clear, not overly cluttered by replays, graphics or taped inserts. For a welcome change, these extras accented the action rather than overpowering it. . . . Overall NBC deserves credit for doing a solid job of bringing major league baseball back into our living rooms.”

But NBC did not get its record viewership. Not close. The game drew a 20.1 rating, down 25% from the previous year and the worst for an All-Star Game since the one in 1969 was delayed by rain.

Outside Municipal Stadium sat Rose’s $175,000 Rolls-Royce. His housemate had driven the car from Cincinnati, carrying Rose’s 11-year-old son, Petey. The housemate was Tommy Gioiosa. In early 1990, just after Pete was thrown out of baseball, Gioiosa would be sentenced to five years in prison for transporting cocaine and hiding Rose’s racetrack winnings from the IRS. (He served 38 months.) Gioiosa also was a steroid user who said during his trial he regularly placed bets for Rose with bookmakers.

After the All-Star Game, at 1:30 a.m., Rose and Gioiosa, with Petey in the back seat, began a shared 8 1/2–hour overnight drive to Philadelphia. But along the way they ran into road closures. Rose had consulted with AAA, but instead chose to take his own “scenic route.” To navigate he used the stars. His guide was the Big Dipper. Or maybe it was the Little Dipper. He wasn’t sure.

They covered the 430-mile trip in 499 miles, pulling into Philadelphia at 10 a.m., 11 hours before first pitch. Rose slept all day. “The latest I ever got to the ballpark,” he said.

He did benefit from an extra hour. The Phillies started the game an hour later to accommodate ABC’s Monday Night Baseball, which was televising the Reds at the Dodgers and planned to cut away to carry each of Rose’s at bats live.

In front of 60,561 fans at the Vet, Rose went hitless his first three times up. His bat was slow, and he knew it. For the fourth plate appearance, Rose switched from a 33-ounce to a 32 1/2–ounce bat. When Cardinals pitcher Mark Littell tried to bury a 0–1 fastball inside, Rose sliced it into left field for the record-breaking hit. (The next day so many people played 3-6-3-1 in the Pennsylvania Lottery that the lottery commissioner stopped action on it.)

During a news conference after the game, Rose was told to stand by for a call from President Ronald Reagan, who five months earlier had been shot in an assassination attempt. Technical glitches kept Rose waiting. He used the time to entertain the media.

“It’s a good thing it isn’t a missile on the way.”

“Can you imagine? They can send a man to the moon but I can’t talk to the president.”

Finally, the call connected.

“Hello, Pete Rose?”

“Yes, sir. How ya doin’?” he said to the president. “We were going to give you five more minutes, and that was it.”

***

When the strike ended, Kuhn proposed a split-season format rather than simply play out the season as one. Teams in first place at the time of the strike were declared “first half” champions, with more playoff spots up for grabs in the second half. Dick Young of the New York Daily News sagely predicted what would happen in 14 years: “It is a version of the NFL wild card and could hasten the day that baseball adopts the wild card system.”

Kuhn’s plan allowed teams that otherwise would be out of the race to compete anew for a playoff spot (and sell tickets). The split season also created another layer of playoff games, the division series, which offered a chance for MLB to recoup some of the financial losses from the strike.

Under Kuhn’s plan, if the same team finished first in both halves, the club with the second-best overall record would be allowed into the postseason. The reaction was scathing. People hated it. Never before in baseball could a second-place team get the chance to win the World Series.

“The entire concept is so stupid I can’t believe we’re going to ask the American public to buy it,” said Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog.

Cardinals executive assistant Joe McDonald called it “the most unjust, irrational concept ever perpetrated in baseball. To go into a season with one thought—to win your division—then change midseason is unthinkable.”

The Reds lost the first half to the Dodgers retroactively by a half-game. They played one fewer game than Los Angeles. The difference? On May 26, Cincinnati was leading the Giants 6–0 in the third inning before rain wiped out the game.

“The commissioner must take full responsibility,” Reds president Dick Wagner said. “It was a situation that required surgery and was treated with Band-Aids. The change is simply an easy way out and whitewash by baseball’s leadership.”

Sharp thinkers such as La Russa and Herzog quickly figured out that Kuhn’s plan could create a finish in which a team lost games on purpose to allow the first-half winner to win the second half, opening a back door to the postseason for the club with second-best record combined between the first and second halves. Both managers said they would do that if it meant qualifying for the playoffs. “I’ll activate myself,” Herzog said. “I’d be the catcher and I’d have players throw with the other hand.”

The owners called for a meeting on Aug. 4 to ratify Kuhn’s split-season plan, but it had to be postponed. The air traffic controllers were on strike.

On Aug. 20 the players association approved the plan with one change to the original proposal: If the same team won both halves, it would play the second-place team of the second half, closing the loophole to incentivize losing.

Cincinnati and St. Louis finished with the two best overall records in the NL. Neither made the playoffs.

***

Network entertainment executives hung on details of Kuhn’s plan, especially how another round of playoffs would affect the start of the World Series. (It would begin on Oct. 20, one week later than originally scheduled.) Baseball was king.

Wrote the Daily News, “The October classic always results in a top rating for the network televising the event, an event which leaves program competition floundering at the bottom of the ratings pile. Therefore, no network wants to book a premiere or any show of consequence against the fall classic.”

NBC said it would not start its new fall season until after the World Series. ABC even postponed new episodes of its hit show, Dynasty, choosing to air reruns until the baseball season concluded.

But those days when baseball ruled television were ending. The 1981 All-Star Game was the canary in the coal mine, and the canary died. The anger and inertia from the strike remained. Kubek admitted as much. “I’m having a hard time now,” he said before his first Saturday Game of the Week. “Once in the booth I could put aside the stuff happening off the field. Now I can’t. The cynicism and bitterness of the strike has affected everything. I’m not sure what my role as a broadcaster ought to be.

“Everyone is still hung up on the strike. The owners have screwed things up so badly they’ll never get unscrewed.”

***

Only 7,551 people showed at Wrigley Field—down more than 20% from the average crowd that year in Chicago—to watch the first major league game in two months. In a matchup of the two worst NL teams from the first half, the Mets beat the Cubs in a sloppy game, 7-5, in 13 innings.

Said New York slugger Dave Kingman, who had not picked up a bat in five weeks, “The pitchers weren’t really sharp. The hitters weren’t really sharp.”

Attendance around the league sank 20%. The Padres did draw 52,608 to their reopener–their largest crowd ever–but that was because owner Ray Kroc let people in for free. When they asked fans to pay for the remaining six games on the homestand, the Padres drew a total of 35,499, or fewer than 6,000 per game.

Back in the Kingdome for the first time, the Mariners drew 14,527, slightly better than average, because of a pregame “money grab” radio promotion to mock the players’ supposed greed. With $10,000 scattered around the field, one fan had one minute to gather as much of it as possible. He netted $1,103. Less than half as many people showed the next night.

The Orioles won their reopener in front of 19,850 fans on a walk-off hit by outfielder John Lowenstein, surprising Lowenstein himself, who said, “It’s not easy to hit after being off seven weeks and practicing seven days. I did not hit one ball during the strike-—a golf ball, a baseball, any kind of ball.”

***

The strike happened because of players like Rose. Once an arbitrator struck down the reserve clause in 1975, owners could not control their spending in free agency. Rose made $375,000 in 1978 with Cincinnati, then hit the open market for the first time. The Reds offered him $450,000 a year for two or three years. Philadelphia vice president Bill Giles offered him $800,000 a year for four years. At the time, Nuggets guard David Thompson was the highest paid athlete in the U.S., at $800,000 annually.

Rose looked at Giles and said, “Maybe it’s an ego thing, but it’s taken me a long time to reach the top of my profession. I’d like to be the highest-paid player in sports.”

“O.K.,” Giles said. “810.”

Rose never missed a game with the Phillies over the next four years, including before and after the strike in 1981. On Sept. 24, playing a series in St. Louis for the first time since breaking Musial’s record, Rose was jogging off the field after the eighth inning when two fans seated near the Phillies’ dugout shouted vulgarities at him and threw beer toward Philadelphia players. A scuffle ensued. One police officer and one fan were taken to hospitals. Two fans were arrested and charged with third-degree assault, peace disturbance and interfering with an officer.

Rose was issued a summons for “individual peace disturbance.” Police alleged he banged on the top of the dugout with his bat. The fans claimed Rose took a swing at them with the bat.

Said Rose, “If I’d swung at them, I would have hit them, the way I’m swinging.”

Rose finished the season hitting .325. At age 40, he became the oldest league leader in hits.

The Phillies, the defending champs and the first-half NL East winners, were eliminated in the best-of-five division series by the Montreal Expos, the second-half winners. After a 3–0 loss in Game 5, Green lamented, “We were robbed of everything we had going for us in the first half. We lost those 50 games, and as a result, we lost 1981.”

Phils reliever Tug McGraw said, “I just have a really empty feeling right now. I feel really bad that the baseball season’s over, on one hand. But on the other hand, I’m looking forward to a real baseball season in 1982. I don’t ever want to go through another of these split seasons again.”

Said Rose, “I’m not going to stand here and say they’re a better team than we are, but we got outplayed.”

The Dodgers beat the Yankees in six games to win the World Series, which drew a 30 rating, down 9% from when the same teams met three years earlier. A steady decline in viewership has ensued ever since. The World Series last season drew an 8.1.

During the ’81 Series, Rose flew to Japan to sell bats and noodles for three weeks. He jetted back to the States in time to receive the Athlete of the Decade Award, as voted by more than 4,000 sports journalists. O.J. Simpson finished second. The award was presented at a black-tie dinner at a swanky New York City hotel. Only two people seated at the dais table did not wear a tuxedo: the priest who delivered the invocation and Rose, the guest of honor that night.

“The last time I wore a tuxedo I got married in it,” he said. “I’m not putting another one on.”

***

What Watergate was to the presidency, the 1981 strike was to baseball. Never again would we look at either institution with the same amount of faith.

Baseball in 1981 returned to cold shoulders, protests and resentment. A return this time offers an inverse public opportunity. Even if relegated to empty ballparks in the interest of public health, baseball as an episodic television and radio option can be a welcome therapeutic for a world slowly emerging from the sacrificing and suffering of the pandemic. In that sense of public healing, baseball could return in a role similar not to 1981 but to ’42, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt famously argued the importance of keeping baseball going during the war, and to 2001, when baseball returned one week after the attacks on 9/11 with deep social import.

We live in disrupted times. Airplanes don’t fly. The best restaurants close. Handshakes threaten. The drumbeat of baseball stops. When and if baseball returns, it, too, will be disrupted. Rules, rosters, schedules, the postseason format, the crowds . . . all are subject to change. When life cuts a major league season to unprecedented brevity, the solace is not that baseball looks the same, but that there is baseball at all.