'We’ve Got No Chance': Pirates Remember Stephen Strasburg's Debut, 10 Years Later

Don Long’s tone was grave. His players were about to face the most-hyped pitching prospect in history, and he wanted to make sure they understood what awaited them. So the Pirates crowded in the players’ lounge behind the visiting clubhouse at Nationals Park and listened to their hitting coach.

“We’ve got no chance against this guy,” Long said. “He throws a thousand miles an hour. He’s got a spitball, a knuckleball, a three-seamer. You don’t even need to take your bats up there. Just tip your cap.”

The room erupted.

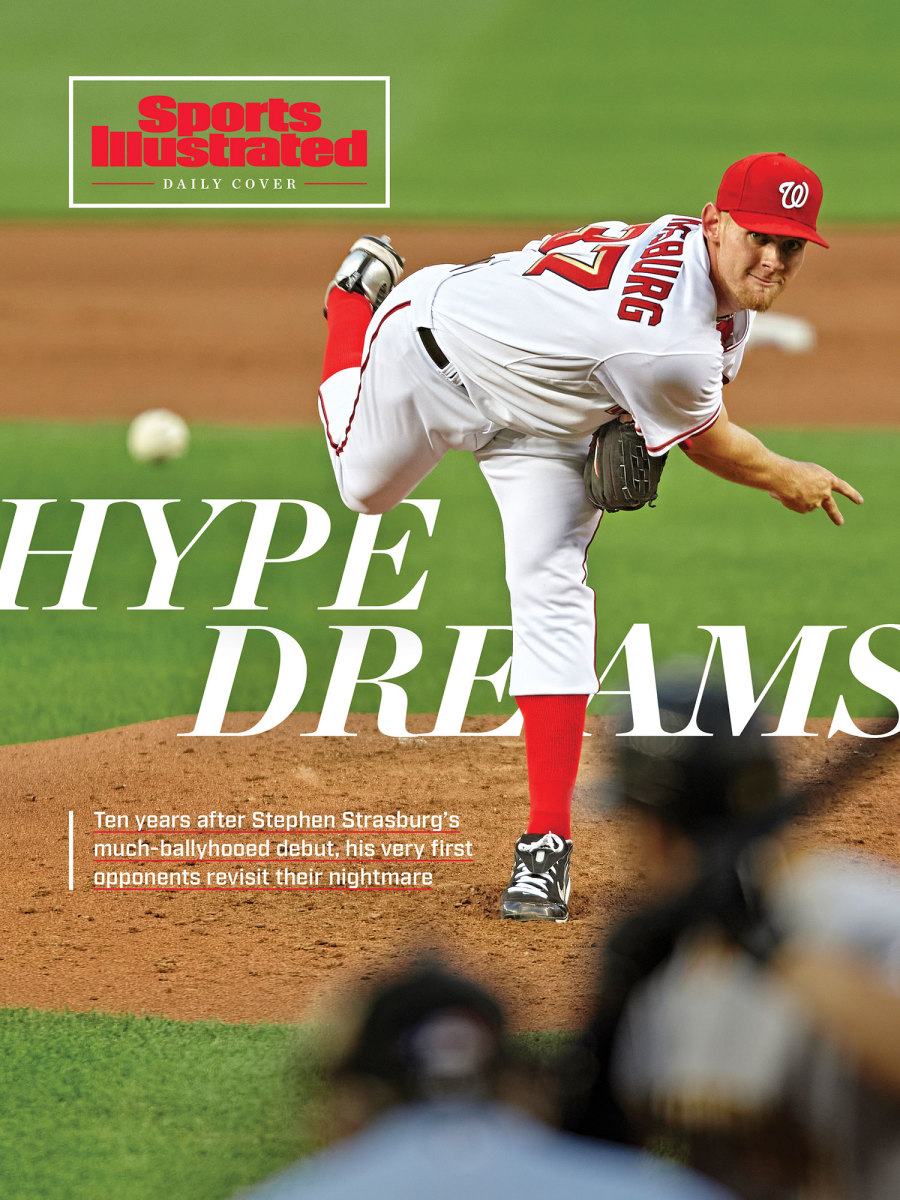

Ten years ago Monday, 364 days after the Nationals selected him with the first pick of the 2009 draft, Stephen Strasburg made his major league debut—and history. Strasburg would become a three-time All Star, a perennial Cy Young Award candidate, the MVP of Washington’s first World Series championship. But first he was a rookie, climbing a major league mound for the first time.

That night marked the first time a player opened his career by striking out 14 without allowing a walk. It lifted Washington’s record to 28–31 and dropped Pittsburgh’s to 23–35. It gave the winners one of the highlights of their careers. And it gave the same gift to the losers.

***

Some 24 hours before Strasburg took the mound, the Nationals made their second consecutive first draft pick: junior college outfielder Bryce Harper. For a franchise that had not finished better than fourth in the division in its five years in D.C., those few days in June felt like the beginning of something.

For the Pirates, they represented more of the same. The 2010 team would go on to lose 105 games. The year before, they lost 99. The year before that, 95. Pittsburgh had not produced a winning season since 1992. The team regularly played before crowds of 9,000. Fans would sometimes break into cheers for the Steelers and Penguins. The players could hear individual hecklers.

In late May, the news broke that the Nationals were considering calling up Strasburg. The excitement around him was tremendous. He touched 100 mph in college, then signed—77 seconds before the deadline—for $15.1 million over four years, the most in history for a draft pick. Washington sent its head of media relations with him to the Arizona Fall League for his professional debut. ESPN nationally broadcast his Double A debut. His minor league starts drew more fans than did Pittsburgh games.

So when the Pirates noticed that his start schedule put him on track to face them, they felt that lucky: They might be relevant, if for only one day.

***

The Pirates had been hearing for days about what an event this would be. Strasmas, they called it, like Christmas. But when the team bus had to crawl through traffic on the way to Nationals Park, they began to realize just what was coming.

Pittsburgh was planning to call up its own right-handed first-rounder—Brad Lincoln, whom it had taken with the fourth pick in 2006. Because of an off day and a rainout, he would have slotted in on June 8. Instead, the team told righty Jeff Karstens the weekend before, Karstens would start on six days’ rest. Lincoln would debut on June 9. As he arrived at the stadium, Karstens noticed lines of fans outside … three and a half hours before first pitch.

The Nationals had issued some 200 media credentials, and it seemed like every one of those people was in the visiting clubhouse before the game, asking how the Pirates felt. It’s just another game, they insisted, sort of believing themselves. They navigated through the crowds of reporters on the field, dugout to dugout, for batting practice. Washington opened the stadium an hour early. The park was beyond sold out: The Nationals exhausted standing room only and began selling luxury-suite tickets by the seat. A stadium that usually hosted 20,000 people suddenly teemed with 40,315.

Fans stood six deep around the bullpen as Strasburg warmed up. They gave him a standing ovation as he strode to the dugout after the national anthem.

“I never got the chance to play in a playoff game,” says then Pittsburgh third baseman Andy LaRoche, “but that’s what I imagine.”

Amid the mayhem, the Pirates tried to keep the mood light, beginning with Long’s speech. Center fielder Andrew McCutchen would win the NL MVP Award three years later, and second baseman Neil Walker would win a Silver Slugger in 2014, but in ’10, the Pirates lacked experience. Long was not concerned that his hitters would fear Strasburg. It was almost the opposite, he says now: He worried that they would be too excited. “It’s more of a calming down,” he says now.

To the question of what was in Strasburg’s arsenal, right fielder Delwyn Young chirped, “What’s he got? Two eyes, two ears, a nose and a mouth.”

Still, no one missed the magnitude of the moment. Before they took the field, LaRoche grabbed McCutchen, who was leading off.

“Tell me you’re taking a first-pitch hack,” LaRoche said.

“Do you think I should?”

“Most-hyped debut of all time. If you put one in the seats, think about that!”

“Yeah, O.K.”

“He gets up there and takes the first pitch,” LaRoche remembers now. “When he came in I was shaking my head. ‘What happened to that first pitch?’ He just laughed it off.”

That first pitch was a 97 mph fastball inside. As the numbers from the radar gun flashed on the scoreboard, the crowd let out an ooh. McCutchen was actually following the game plan: See if the rookie shows jitters.

“We waited to see if he could find the strike zone,” says Pirates manager John Russell. “Obviously, he did.”

On the third pitch, McCutchen lined out. Walker grounded to first. Left fielder Lastings Milledge provided Strasburg’s first major league strikeout.

Out in the bullpen, pitching coach Ray Searage was staring, agape. So were his relievers. They punctuated particularly filthy offerings with gasps.

“I felt bad for our hitters,” Searage says. “You hear hype and you’re like, Let’s see what we got. I was thinking, Oh my God, the hype is right. They undersold him.”

***

First baseman Garrett Jones led off the second. In time, he would come to despise Strasburg’s sinking changeup—”It had so much fade away from left-handed hitters,” he says. “It would just die late. I remember a lot of swing-and-misses, a lot of ground balls”—but on this day he was awed by the whole mix. As he returned to the dugout after striking out, he warned his teammates to look for the fastball—it was the only thing they might be able to hit.

Next came Young, who grew up two and a half hours north of Strasburg in Southern California and had followed the pitcher’s career. Young had spent three seasons with the Dodgers before being traded to Pittsburgh, and he longed for those packed stadiums. So while some of his teammates battled butterflies, the roar of the crowd actually slowed his heart rate.

He was eager to see Strasburg for himself. In the days before ubiquitous video, the team mostly had to rely on scouting reports. Bench coach Jeff Banister had been the opposing manager for the AFL debut, and he passed along some advice: Don’t miss the first pitch you get to hit, because you’re not going to get another one. But for the most part, they were guessing.

“It’s like riding a bull,” says Young. “You have an idea of what this animal can do, but you don’t know how it turns and how it bucks until you get in there.”

The scouting reports had warned Young about an electric four-seamer, a changeup that dropped off the table, a darting two-seamer and a devastating curveball. He took a two-seamer for a strike, then a changeup for a ball. (“I still regret taking the first one,” he says. “Ten years later i’m still kicking myself. Could’ve broken my bat. Could’ve hit a light. But I took it.”) He fouled off a changeup. He took a four-seamer—100.1—for ball two. Then he swung two feet over a breaking ball.

He saw McCutchen as he returned to the dugout. “Buddy,” Young said, “That’s a slider. That is not a curveball.”

LaRoche headed toward the plate. He was nervous, he can admit now, but he enjoyed that sensation. Baseball is such a grind that it can be hard to slow down and appreciate the moment. “Not saying you just take it for granted,” he says, but still. Amid 100-loss seasons, it felt good to feel something.

He decided to take the first pitch in the hope of timing up the four-seamer. Strasburg threw him a curveball for strike one. So much for that, LaRoche thought. The second pitch was a four-seamer, inside. The third pitch was another fastball. LaRoche told himself to keep his swing short. He lined the pitch to right field, breaking up the no-hitter. The crowd booed him.

“I got booed at home and on the road,” he says now. At least boos on the road are a compliment.

Strasburg struck out shortstop Ronny Cedeño to end the inning, then whiffed catcher Jason Jaramillo and Karstens to open the third. Karstens felt nervous in the first and allowed a solo home run, but he had settled down and was eager to see Strasburg from 60 feet, six inches away. “It was cool and all until he threw me curveballs,” he says. “I was like, Man, you’re throwing 100 mph and you’re throwing me curveballs!”

McCutchen grounded to third to end the inning.

***

Walker singled to open the fourth. Milledge singled. Jones grounded into a double play.

Young took a fastball inside for ball one. In the absence of much information about Strasburg, the Pirates decided to try to scout his catcher, Hall of Famer Iván “Pudge” Rodríguez. Young decided to look for a 1–0 fastball inside, then at the last second changed his mind. He’s not gonna double up, he decided. He thought Rodríguez might call for a changeup. He stayed back. He got his changeup.

“I knew I flushed it,” he says. “Generally when you flush something like that, you don’t feel it. I felt the purity of the swing.”

As he rounded first base, he heard the whoosh of air from the fans. That was always his favorite sound—the instant when he silenced the home crowd. “It was like, Muhammad Ali can get knocked down!” he says now. “Oh, my God, he’s real! He’s not striking everybody out! He is touchable!”

The Pirates led the phenom 2–1. We can’t give anything else up if we’re going to win this game, Russell thought.

A fan threw the ball back, and someone collected it for Young. He kept it and the bat.

On deck, LaRoche, Young’s roommate and future groomsman, was going nuts.

I’m gonna go back to back! he decided. We’re gonna show this rookie! I’ll ambush him.

He swung at the first pitch … and popped it to second.

***

“It seemed like Strasburg said, ‘No, no, no, boys,’ and stepped on the gas,” says Banister.

Cedeño struck out to open the fifth. Jaramillo grounded to first. Karstens struck out. “I fouled a couple pitches off,” he says now, “So I was proud about that.” (His goal entering the game had been to see five pitches in each at bat. He figured that a big-time prospect was likely to be on a pitch count of 100 or so, and if he could make him waste 10% of that on the pitcher, he had done his job. He ended up seeing exactly 10.)

In the top of the sixth, McCutchen struck out swinging. Walker struck out swinging. Milledge struck out swinging.

Out in the bullpen, Searage continued to marvel. The hitters couldn’t identify what was coming until it was too late.

“You’ve got ‘tunneling’ nowadays,” he says, “But we were tunneling a long time ago and it wasn’t called tunneling. You want things to come out with the same trajectory. That’s what makes you deceptive.” (“Uncle Ray doesn’t like to give up to the analytic terminology too much,” says Banister with a laugh.)

For all Strasburg’s dominance, the Nationals still began the bottom of the sixth down 2–1. Karstens coaches at Berkeley (Fla.) Prep now, and one of his players recently texted him: Coach, you’re on TV! He turned it on and watched happily until the sixth inning began. “We can turn it off now,” he said.

“I can close my eyes and visualize the home runs,” he says now. First third baseman Ryan Zimmerman singled. Then first baseman Adam Dunn deposited a sinker in the right field bleachers. Karstens threw left fielder Josh Willingham a slider that didn’t slide. Home run to left. 4–2, Nationals.

“You feel the earth shaking,” says Young. “I’m a southern California boy. I know what that feels like.”

***

Jones struck out swinging to open the seventh. Young struck out on a foul tip for strikeout No. 13. It was at this point that the occupants of Nationals Park learned that the scoreboard K counter went up to only 12.

“Why would I have had to know that?” team president Stan Kasten said after the game.

All game, the crowd had continued gasping at Strasburg’s velocity readings. “You would think the fans were little kids,” says Karstens. Now he sat on the bench and listened to the roar. At first, the fans stood for every two-strike count. By the end, they were standing for every strike.

“I don’t think it could’ve happened in a better city,” Young says now of America’s baseball-starved capital. “No disrespect to the rest of the teams, but if he did it in Baltimore, would it have been as epic?”

LaRoche strode to the plate. Strasburg had thrown 91 pitches; LaRoche knew the rookie’s night must be almost over. (In fact, it was scheduled to be over an inning earlier, but manager Jim Riggleman and GM Mike Rizzo agreed that he was so efficient and his delivery so effortless that he could be allowed to pitch the seventh.) LaRoche took a curveball for strike one. He swung at a curveball for strike two. And he swung at a fastball for strike three. No. 14. History. The ballpark shook again.

“I was so mad,” LaRoche says. “I just wanted another chance to quiet the crowd.”

***

The Nationals scored again in the eighth. They won 5–2 in a snappy two hours and 19 minutes. Strasburg endured three celebratory shaving cream pies to the face and was crowned with the plastic Elvis hair the team bestowed upon the player of the game. Young was dragged from the cold tub to conduct an on-field interview in his wet clothes.

For weeks afterward, people questioned them about that day: fans, other players. “Nobody asked me what it was like to face Chad Billingsley,” Young says, before adding, “I love Bills!”

As the Pirates slogged through another losing, sparsely attended season, they thought sometimes of the night people actually watched them play baseball. And as the years passed and they reflected on their time in Pittsburgh, many of them found themselves returning to a surprising favorite game: a loss.

At the time, frustration mounted along with the strikeouts. “Nobody wants to suck on national TV,” says Karstens. But now, he says, “I’m just glad I got to be a part of it.”

Young goes further. He compares that day to an eight-year-old’s first trip to Disneyland, to an adult’s wedding day. He sighs. He says, “I wish there was a way we could do it again.”