How the Rays Became MLB's Outliers by Finding MLB's Outliers

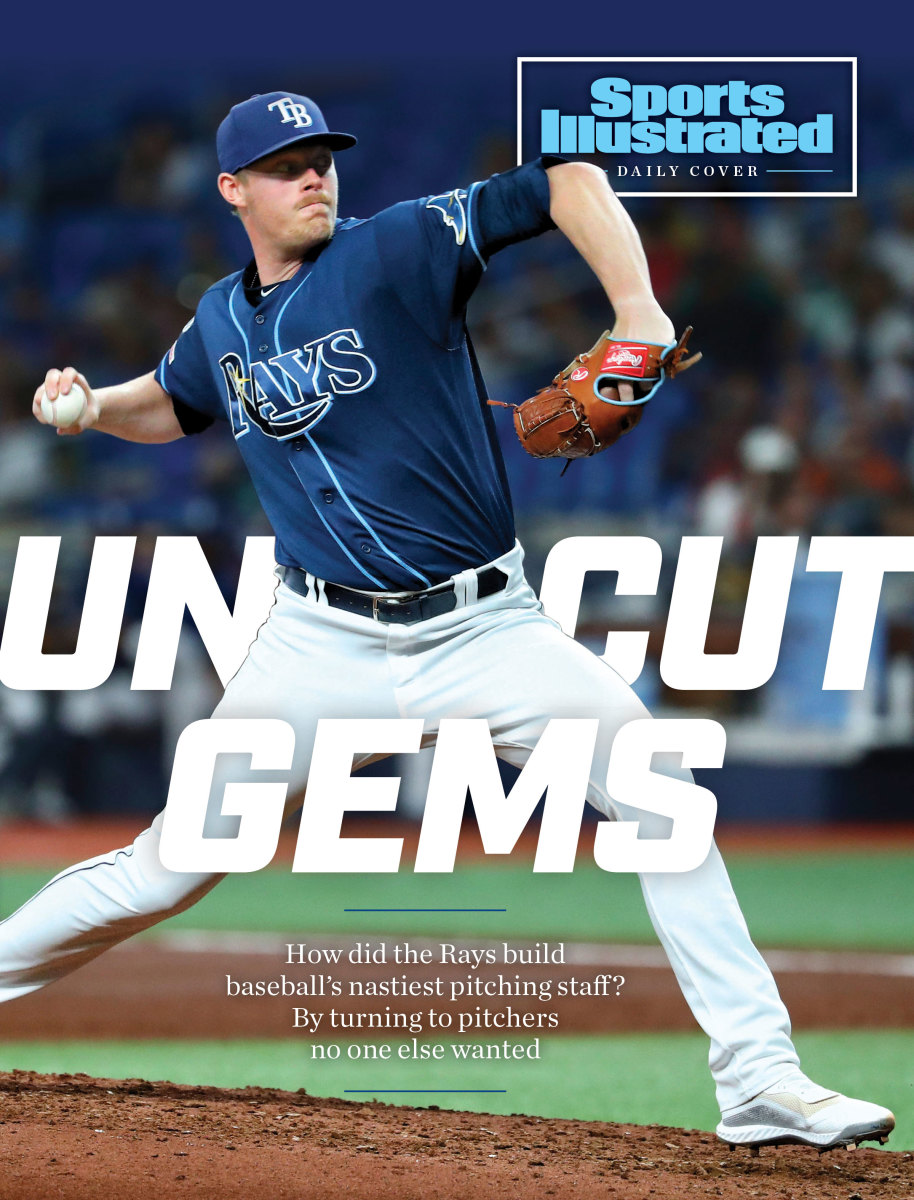

The Rays are the most dangerous team in a shortened baseball season with expanded rosters. If you want to know why, a good time to start is July 13, 2019. Almost nobody noticed when Tampa Bay made a trade that day for Peter Fairbanks.

“Peter Fairbanks” sounds like a character from a 1941 Bob Hope comedy, which he actually was (Caught in the Draft). This Peter Fairbanks might have been even more anonymous. A right-handed pitcher, he posted a 9.35 ERA in eight games for the Rangers, looking for all the world like just another fungible reliever among the record 698 fungibles that came out of bullpens last year, more than twice as many as were needed in 1992.

That he was in the big leagues at all made for an incredible story. The quick version of his backstory goes like this: A ninth-round pick out of Missouri, by age 24 he owned a 4.42 ERA in minor league ball, two Tommy John surgeries and a dim future in the game.

“I thought I sucked and I wasn’t staying healthy,” Fairbanks says.

So this is what he did: With the help of the internet, he taught himself a completely new way to throw a baseball. His fastball shot up from 92 mph to 98 mph. Though he wasn’t invited to big league camp and started the year in A ball, by June 9 he was in the majors.

“After the season,” he says, “I was like, ‘Wow, did that really all happen in a year?’”

The Rays are the Antiques Roadshow of baseball. They find Picassos in attics, Tiffany lamps in basements and pitchers with outlier stuff in the dumpsters of other organizations.

In Fairbanks they saw not just velocity but also near-perfect backspin on his four-seamer, which they and other smart clubs know is the proven antidote against the launch-angle hitting revolution. To get Fairbanks they traded Nick Solak, a promising hitter without great defensive value.

Since joining the Rays, Fairbanks has improved his stuff even more, thanks to the wizardry of pitching coach Kyle Snyder and process and analytics coach Jonathan Erlichman, a former math major and club hockey player at Princeton.

“Our guys do a tremendous job looking for the guys they acquire as far as special, special stuff,” Rays manager Kevin Cash says. “[Fairbanks] is right at the top of the list. You don’t see many guys with that high average (velocity) and the type of carry that he gets and have the ability to land a really, really quality breaking ball.

“He’s basically Diego Castillo. He four-seams it. Diego sinks it. Both throw their breaking ball, which is nasty, at any time.”

In less than a year with the Rays, Fairbanks, 26, has learned this much about the organization when it comes to pitching: “They’re ahead of the curve. I would say they set the curve for pretty much everything. This staff I would say probably has the best collective stuff in baseball.”

Allow me to be more definitive: From pitchers one through 15, the Rays have the best pure stuff in baseball.

A short baseball season plays to their strength. A short training period and 15-man pitching staffs will further devalue length from starting pitchers. Workloads will be spread among more arms. No team is better prepared for this kind of baseball than the Rays, who not only prefer this style but also have the most elite arms to exploit it.

How they assembled this group is nothing short of amazing. Among their finds are a former NAIA pitcher from Mayville, N.D.; a 33-year-old Naval Academy grad who washed out with six other teams; a former 14th-round pick by the Diamondbacks who throws almost nothing but average-speed fastballs; a “funky, goofy” bespectacled left-handed pitcher who lost 70 pounds and throws 97 who they found this winter on the internet; and the incredible Mr. Fairbanks.

The Rays won 96 games last year with the lowest payroll in baseball at $64 million. In the past decade (2010–19) only three teams won 90 games six or more times: the Yankees, Dodgers and Rays. The Yankees spent $2.07 billion to do so. The Dodgers spent $1.92 billion. The Rays spent $666 million.

How do they do it? The story of Peter Fairbanks is the story of the Rays. I am fascinated by it.

“So am I,” Cash says.

***

In the summer of 2010, between his sophomore and junior years at Webster Groves High School in Missouri, Fairbanks topped out at 85 mph with his fastball. He was 16 ½ years old and weighed 185 pounds on a 6' 5" frame. He had not yet filled out but had the long levers college coaches like to see in pitchers. On the showcase circuit that September he hit 87 mph.

One day the next spring, Missouri offered the junior a scholarship. The next week Fairbanks tore the ulnar collateral ligament in his right elbow. He was 17 years old and needed Tommy John surgery. Missouri reduced his scholarship.

“My rehab the first time was nowhere near as good,” he says. “I don’t even remember the first. I had it, I got healthy and it took me a while to get right at Mizzou. My freshman year I threw six innings. I was awful.”

Fairbanks progressed well enough to be drafted by the Rangers in the ninth round. He threw around 92-93 mph. But when it came to arm health, Fairbanks was a ticking time bomb.

Pitchers get hurt. It happens. But contrary to popular belief, throwing is not an unnatural motion. A 2013 study at George Washington University found humans’ ability to throw fast and accurately to be unique on this planet, having first evolved about two million years ago to aid in hunting. We are built to throw. The two greatest risks at compromising that ability are overuse and poor mechanics. Fairbanks made it to Division I baseball and to professional baseball with lousy mechanics.

“I don’t know if you’ve seen any video of me before, but it was really bad,” he says.

The red flags were numerous. Fairbanks had an extremely long arm swing, which would cause him to be late to the loading phase. (When his front foot landed the ball had not yet reached the “loaded” position above the shoulder, as it should.) The long arm swing also created inconsistency in his timing and release point.

He had no shoulder tilt. He raised his back elbow above the shoulder before turning the ball up toward the loaded position. When he did load, the ball was too far away from his head, a malady known as “forearm flyout” because the pitching forearm is too flat. In a properly loaded position, the upper arm and lower arm should create an angle between about 80 and 100 degrees. Fairbanks’s angle was well past 100 degrees.

After fewer than 200 innings of minor league ball, Fairbanks blew out his elbow again. Asked whether poor mechanics contributed to his surgeries, Fairbanks says, “Definitely. I think the arm was late getting up. I was not using my legs properly. I was kind of pushy. I was pushing straight into extension, which caused me to sweep, and everything was going forward before I was in that 80–100 degree range. And I couldn’t stay healthy doing it.”

Fairbanks knew he could not keep pitching like this. Something drastic would have to change. And then he noticed Joe Kelly.

A Cardinals fan growing up, Fairbanks remembered how Kelly threw with a “super, super long” arm swing when he first came up with St. Louis. But when Fairbanks saw him in 2017, he saw a different pitcher. When Kelly took the ball out of his glove, he brought it straight back rather than down, severely truncating his arm stroke.

“When I saw him again, he had changed it up and he was throwing a hundred miles an hour,” Fairbanks says.

Kelly had worked with Dave Coggin, a Phillies pitcher from 2000–02 who ran a training center in Upland, Calif. Fairbanks studied Coggin’s ideas and drills on the internet.

“I kind of stole stuff from him and started working on it in the offseason of ’17 because I just had surgery in August,” he says. “So I was at home, from November to April, basically just trying to figure out how to do it.”

His second Tommy John surgery required that he not throw for eight months. He used that time to study his new throwing motion and strengthen his body. When he was cleared to throw, he began with a simple drill in which he tossed a ball on one knee. But instead of throwing with his left leg forward, he put his right leg forward. By leading with his opposite leg, Fairbanks was forced to throw with a shorter arm movement. It wasn’t physically possible to use the long arm swing that had come naturally to him. He was learning how to throw all over again.

The opposite-knee drill provided the foundation as Fairbanks graduated to playing catch at 60 feet, then 70, then 90, then 100, then 120. … His rehab coordinator, Keith Comstock, and medical coordinator, Sean Fields, kept a close eye, often videotaping his throwing session to make sure he maintained the short arm stroke as the distances grew.

The result was stunning. Fairbanks successfully had relearned to throw with a more efficient delivery: a short arm stroke just like Kelly, proper shoulder tilt, a 93-degree bend of his arm in the load phase. The ball came out of his hand like never before. He was by definition a different pitcher. (Lucas Giolito of the White Sox is another pitcher who successfully overhauled his arm stroke to be shorter.)

“I didn’t think it was going to be too hard to do because of how I was able to do it,” Fairbanks says. “If I had to do it in any [normal] offseason and go, ‘All right, I’m going to change all this in three months and still have the muscle memory of going like this [with a long arm swing],’ I think it would be a lot harder.

“But basically, because I had a blank slate and didn’t throw for so long, I could just tell myself, ‘O.K., this is how you throw, and we’re going to keep it right there [at the waist] and get it up.’”

On June 29, 2019, the Rangers brought in Fairbanks to pitch the seventh inning against the Rays at Tropicana Field. The first batter, Wily Adames, hit a home run. The second batter, Travis d’Arnaud, also homered. But then Fairbanks struck out Austin Meadows on a 91 mph slider that bounced on the plate, struck out Kevin Kiermaier on a called 99 mph fastball, and struck out Tommy Pham on a 91 mph slider that so badly fooled Pham the outfielder snapped his bat in half over his knee.

“We hit him pretty good for whatever reason, but his stuff was electric,” Cash says. “Throwing 99, landing sliders. … I remember our [front office] guys saying after the game, ‘We really like that guy.’ ”

Two weeks later the Rays traded for him.

***

The crown of the bell curve is the worst place to be for a pitcher.

Hitters see so many pitches that the way they process so much information is an adaptive mental technique called “chunking.” Thousands upon thousands of pitch trajectories give a hitter a sense of where the pitch is going.

Imagine you’re driving in a city for the first time and stopping at a red light. When will it turn green? Though you haven’t sat at this light before, you have an idea of when it will turn green based on the hundreds of previous red lights you’ve encountered. You have “chunked” all that information into one expectation, and chances are it will change about the time you expect it will.

But what if that light is especially short or especially long? It’s an outlier light. Now your chunking technique has failed you, because it works best on the crown of a bell curve.

This is what it is like facing Tampa Bay pitchers. Almost every one of them is an outlier. Just about nobody among them throws a baseball that fits in the crown of a bell curve, either by stuff or the manner in which it is delivered.

Here are some of the Rays’ outliers:

• Diego Castillo: He throws the hardest sinker in the majors (98.2 mph on average; min. 300 results).

• Jose Alvarado: He throws the second-hardest sinker (98.1).

• Collin Poche: The former 14th-round pick by Arizona throws the most four-seamers in baseball (88.4%), even though it has average velocity. Why? The pitch has the most “rise” of any four-seamer in baseball as a percentage above average.

• Nick Anderson: The Mayville fireballer has the second-most rise on a four-seamer. He struck out 42% of hitters last year.

• Oliver Drake: The righty throws a splitter 59% of the time, the second most in baseball. Lefties hit .152 against the pitch.

• Chaz Roe: On his 10th team, Roe throws 64% sliders, the second-highest rate in MLB.

• Blake Snell: He is tied with Justin Verlander for the second-highest release on curveballs, behind only Ross Stripling.

• Charlie Morton: Only Corey Kluber among starters gets more horizontal break on his curveball.

• Tyler Glasnow: He throws fastballs at an average of 96.9 mph and with the longest extension in baseball. Last year, despite making only 12 starts, Glasnow threw 34 pitches in which he let the ball leave his hand eight feet or more in front of the rubber. All the other pitchers in baseball combined to throw 58 such pitches.

To this group the Rays have added Fairbanks, with his short arm stroke, and D.J. Snelten, 27, the dude they signed off the internet. Snelten was a ninth-round pick in 2013 by the Giants out of Minnesota. In 2018 he contracted the flu just before spring training and arrived in a weakened condition. To ramp up quickly in his recovery he accelerated a heavy ball routine and overdid it. His shoulder stiffened, but because he was trying to make the team, he didn’t tell anyone.

His fastball dropped from 93–94 mph to the high 80s. By June the Giants waived him. He landed with the Orioles, who gave him six weeks to rest his shoulder before sending him to Triple A, where he posted a 5.52 ERA. The next spring, 2019, the Orioles released him. Snelten landed in independent ball with the Chicago Dogs.

This winter Snelten dedicated himself to rebuilding his delivery, especially the manner in which he created power from his glutes. He posted a video in which he hit 97 mph on flat ground in an indoor cage. The Rays not only signed him, they also invited him to big league camp.

“I was talking to our R&D guys,” Cash says. “We have projections on everybody. So I asked, ‘What’s this guy’s projection?’ They were like, ‘We have no idea. The last time we saw him in pro ball he was throwing 87, 88.’

“He’s throwing 96 now, and it’s funky. Big dude. He’s lost 70 pounds. Big kind of goofy guy, glasses, left-handed, funked-up looking windup, and he’s throwing 96 miles an hour with a filthy changeup.”

Cash has so many good options when it comes to pure stuff that last year he used four pitchers at least 36 times in high-leverage spots (Castillo, Roe, Poche and the since-traded Emilio Pagan). Only two other teams trusted so many arms in so many big spots: the Yankees and Brewers.

Overall, the Tampa Bay staff was the second-toughest to hit when measured by OPS (.680). Despite their $64 million payroll, the Rays finished behind only the Dodgers ($207 million) and ahead of the Astros ($169 million).

***

Art Fowler, the long-time pitching coach and drinking buddy of Billy Martin, used to trudge out to the mound to visit a struggling pitcher, head bowed, hands in pockets, as if somebody had ordered him to complete a chore, such as pulling weeds or cleaning gutters.

He would look at the pitcher and say, “I don’t know what you’re doing, but whatever you’re doing you’re making Billy really mad. So stop it.”

And then he’d turn and walk back to the dugout.

Pitching has become intensely granular, packed with information to replace “this is the way we used to do it.” It’s not enough that Fairbanks taught himself to throw harder. He also needs to know how to make the baseball spin properly. How it comes off his fingertips—literally off his fingertips—is a data-driven exercise, not just feel. High-speed cameras can help discern that last critical moment when a ball makes use of all that power created in a delivery and takes flight.

Fairbanks keeps a last thought in mind: let the ball leave his index finger last. That’s mostly an impossibility because the middle finger is longer than the index finger.

“But because I’m thinking more index finger, I’m keeping my wrist behind the ball longer,” he says.

When you throw a baseball your hand naturally wants to pronate as the ball leaves—the thumb turns down and the fingers begin rotating in the direction of what was the inner half of the ball as it faces home plate. That natural movement works fine for throwing a two-seamer because that pitch does well with off-axis spin.

Off-axis spin—or “wobble”—is the enemy of the four-seamer. That pitch in purest form works best against gravity by back-spinning as fast as possible in a true north-south direction. That’s why four-seam practitioners work on keeping the wrist flat and the entire hand behind the ball as much as possible—delaying the inevitable pronation until after the ball is released. Pitchers who can throw four-seamers with close to pure north-south spin have a gift. Poche, for instance, throws a fastball with average velocity (92.9) but held batters to a .173 average on the pitch because of its pure spin. It traffics in its “carry”—it doesn’t sink the way hitters expect with their chunking method.

Some pitchers benefit from physical gifts. Glasnow, at 6-foot-8 and with a long stride, uses extension to his advantage. Pedro Martinez kept the ball on his long, flexible fingers for so long that he developed callouses at the very top of his index and middle fingers, not near the pad.

“Mine’s more from where [the index finger] hits the seam on the way off,” Fairbanks says, pointing to a spot at the side and top of his finger.

Since he joined the Rays, Fairbanks has improved the quality of his spin while working with Triple-A Durham pitching coach Rick Knapp, bullpen coach Stan Boroski, Snyder and Erlichman, who is known as J-Money.

Asked what he has learned since joining the Rays, Fairbanks says, “For me, I know Glass has spoken to this, if you have really, really good stuff, throw it over the plate, because that was the biggest thing I’ve noticed. When I was up with Texas I was too much into stats and the scouting report side of things and the idea of safe zones. I don’t pitch well when I try to be safe.

“I’m going to attack, attack and attack. And that’s when I was at my best last year. I think Snyder and J-Money and everybody that funnels into Snyder and Stan does a fantastic job of figuring out what you need to do.

“Like I’m carrying the ball with backspin better here than it was in Texas, just from working with Knapp when I was in Durham and working with Snyder to figure out where I need to get and to keep my fingers behind the ball and to keep that index finger on as long as I can. It’s never going to be the last finger on, but as long as I think that I can get that backspin.”

***

Hitting has changed drastically in the past five years. Slugging has replaced batting average as the preferred measurement of success. Slug is in the air, so hitters have created swing paths to hit line drives and hard flyballs. Pure four-seam spin defeats such intentions, especially in the upper end of the strike zone. With less sink than a hitter expects, high four-seamers ride over hitters’ swing paths. They are kryptonite to all the power bats in the game.

Pitching has become more of a vertical endeavor than a horizontal one. Consider every fastball thrown last season and divide them into six-inch increments according to their height as they cross the plate. Start with fastballs that are between 12 and 18 inches off the ground–roughly the bottom of the strike zone and just below—and go up to fastballs that are three and a half to four feet off the ground—roughly the upper layer of the strike zone and just above. Now see how hitters fared based on those six vertical layers:

Fastballs by Height, MLB 2019

Feet Off the Ground | Avg. | Pitches |

|---|---|---|

1.0 - 1.4 | .248 | 18,820 |

1.5 - 1.9 | .281 | 43,707 |

2.0 - 2.4 | .321 | 68,078 |

2.5 - 2.9 | .300 | 69,686 |

3.0 - 3.4 | .237 | 51,111 |

3.5 - 4.0 | .125 | 32,860 |

The numbers make obvious what smart teams like the Rays understand: Hitters have a tougher time hitting fastballs when they are elevated. This truism is something that cuts against a century or more of traditional thinking in baseball. Older pitching coaches and former players were taught to “keep the ball down” and that “getting the ball up” was a mistake. Those who keep to those notions are out of touch. The game has changed. That’s why more and more teams are hiring young, data-driven pitching coaches that are not hidebound by tradition.

Last season Houston right-handers Verlander and Gerrit Cole defined the state of the art. They combined to throw 497 fastballs in that top layer and gave up—get this—two hits.

The Rays were among the teams that exploited the pitch most. Only four teams threw more fastballs in that top layer than did the Rays (Boston, Miami, Milwaukee and Pittsburgh). Drake, Anderson, Castillo, Roe, Glasnow, Fairbanks, Morton and Snell combined to hold hitters to a batting average on high fastballs of .047—just three hits all year.

With his four-seam spin and his grasp of pitching metrics, Fairbanks is a perfect fit for the Rays.

“I was really impressed right away with how his mind works,” Cash says, “and the way he’s able to understand a lot of the research and how technology-driven pitching has become. We threw an awful lot at him last year as far as leverage. We put him in roles I can’t imagine many A ball guys had come to: pitching in a tie ballgame at Dodger Stadium with a playoff spot on the line at the end of the year.

“This [year] is unique. This is a first for him. He’s got big league time but he’s never been in big league camp. The confidence that we have in him, we still want to see that confidence in himself. He’s getting there.”

Last year the Rays finished seven games behind the Yankees. The gap between the clubs is less than you think. Tampa Bay went 7–12 last year against New York. Turn just four of those losses into wins, and the Rays, not the Yankees, would’ve won the division.

A shortened schedule this year figures to be heavy with intradivisional games. The Rays’ path to beating the Yankees is to defuse their right-handed power with high fastballs. No team in baseball last year saw more fastballs around the top layer of the strike zone than did the Yankees. They finished in the middle of the pack against elevated pitches at .123, slightly below the league average of .125. D.J. LeMahieu, Gleyber Torres, Luke Voit and Giancarlo Stanton were a combined 1-for-41 against elevated heaters.

The Astros have been a thorn in the Yankees’ side the past two or three years not because they stole signs but because they had Verlander and Cole, the masters of the elevated, pure-spin fastball. Verlander and Cole started 10 games for Houston against New York over the past three years, postseason included. The Yankees went 2–8 in those games while averaging 2.4 runs per game.

This winter Cole switched sides, leaving Houston for New York. Houston no longer poses the greatest threat to the Yankees. It is the Rays, the team that came within one game last year of taking out the Astros. No team in baseball has a better collection of pure stuff. No team has more power, pure spin and carry through the top of the zone.

Fairbanks is just one of the many outlier arms with Tampa Bay. It took two Tommy John surgeries, learning how to throw all over again and a trade that nobody noticed for Fairbanks to wind up in a place he belongs. Peter Fairbanks is the perfect Ray.

“They do some awesome stuff here,” he says.