The Unsettling Ways of Playoff Baseball in a Pandemic

LOS ANGELES – The 110 Freeway flowed freely outside Dodger Stadium. The deadlocked traffic that usually accompanies Dodgers games was nonexistent. The parking lot was a sea of sun-bleached asphalt.

The pregame scene inside the stadium was also out of balance, particularly for a postseason series. This baseball cathedral, where Koufax and Scully had made their names, where manager Dave Roberts’s nucleus of players had come so close to winning it all, where 50,000-plus fans pack in each night–resembled a quiet Hollywood sound stage.

Dodger Stadium had already hosted 30 games this year under the strange terms forced upon it by the pandemic, but none stranger than L.A.'s Game 1 win, 4-2, over the Brewers in the wild-card series. These postseason games were supposed to bring an energy that the regular season had lacked, but virus and its impacts do not concern themselves with such worldly matters.

Dodgers shortstop Corey Seager said during his postgame Zoom interview that he’d almost gotten used to playing in empty stadiums. Until Wednesday night.

“It was a postseason game. For the first time in a while it was weird not having fans,” Seager said with a slight shrug.

“But it’s what we’re doing.”

One of the details that can go unnoticed on a night when there are no fans to witness them (and tweet about them) is that the Dodgers stayed in their tunnel during the national anthem. The ESPN broadcast was wrapping up a pregame studio segment, so its cameras at Dodger Stadium did not show viewers that only Roberts and his coaching staff were standing on the field as the organist played “The Star Spangled Banner.” As soon as the tune finished, the Dodgers emerged from beneath the stadium and filed into their dugout.

The cameras’ red lights came on after that, and the artificial murmur of crowd noise wafted from the stadium’s sound system. Dodger Stadium–all stadiums in these opening games of the postseason–had become, in essence, a massive TV studio. What difference is there between Major League Baseball and other sport-based reality shows, after all, besides 150 years of cultural and competitive nuance, a few detailed statistics appearing on screen, and these sprawling settings that have been designed specifically for this show?

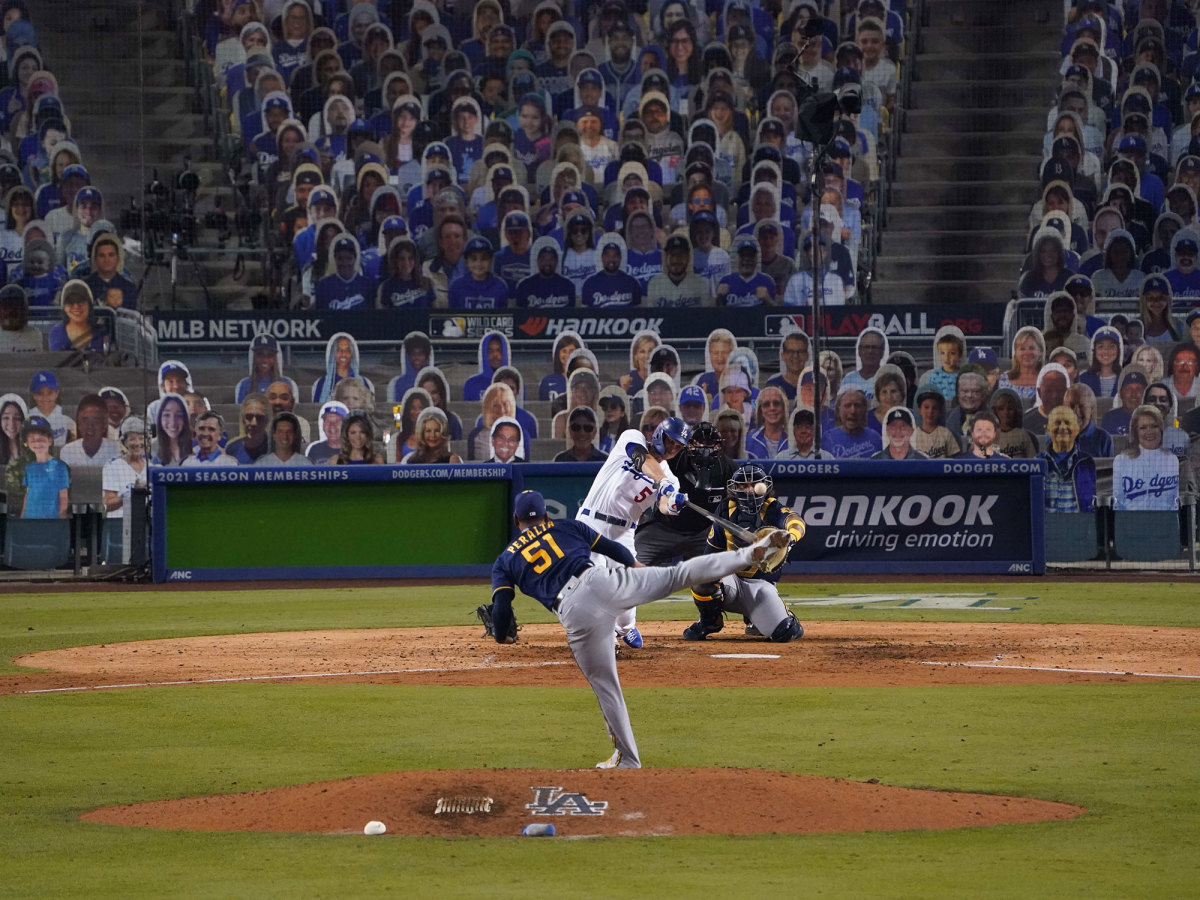

Acres of cardboard fans–no legs, just torsos and smiling faces–had been arranged in sections of the stadium that most often appear on TV. The low seats behind home plate were filled with those two-dimensional cutouts, each one held in place by a plastic cord, while the upper deck and the seats along the baselines were left empty. This bit of stagecraft, at least, was an old hat for a stadium that has hosted dozens of movie shoots over the years in which she has been made to look full when she wasn’t.

Walker Buehler threw his first pitch at a few minutes past seven, and the only people who saw it in person–stadium workers, support staff, groundskeepers and media–might as well have been gaffers, set designers and script supervisors.

It has to be this way, of course. The only safe alternative is to not play the games. And that’s not really an option when there is so much money on the line for the show’s producers, investors, and advertisers.

As it has in most other walks of life, the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, has stripped postseason baseball to its base elements, shaping it into a TV production that, for now anyway, doesn’t require a studio audience in order to be entertaining.

The Dodgers fans who remained at home, meanwhile, are less concerned about the outcomes of Dodgers games these days than they were a year ago. It’s nothing personal. The city doesn’t have the bandwidth. Roiled by months of street protests, counter-protests, and heavy-handed responses by local police, L.A. County has simultaneously seen more citizens infected with coronavirus (255,000) than most U.S. states.

The Bobcat fire, just over the ridge from Dodger Stadium, has razed 114,000 acres and is still burning. A new heat wave arrived this week, combining with the region’s bone-dry conditions to prompt a warning from the National Weather Service of “extreme fire behavior.”

So you’ll forgive L.A. if this pursuit of a World Series trophy feels less vital to day-to-day life than the Dodgers’ previous 24 playoff appearances here. As with the rest of America, L.A.’s institutions are being reduced to their essence. Their insides and deepest motivations have become harder to hide. The Dodgers are no exception, and this new transparency isn’t a choice. It’s part of the deal. And it brings new questions, too, most of which are more important than this one, but here it is anyway:

Why do professional sports exist? For fans? For players? For TV revenue? To decide champions?

“It was different,” Roberts said afterward of the game’s vibe. “The main thing was, the focus on the field was there.” Thank goodness for that bit of purity. Game 1 of the wild-card series was far from a thriller, but the Dodgers and Brewers played as if deeply invested in its outcome. There is beauty in that. There is simplicity, a return to form. If one can somehow tune out the artificial muttering that fills the stadium (it can become cheering at the touch of a keyboard), and if one can look past the absence of tens of thousands of fans, what remains is an elementary game that involves a square of bases set 90 feet apart. In this light, playoff baseball in this first year of the age of coronavirus resembles the sport that was shaped by Alexander Cartwright and his friends in various New York pastures during the 19th century. Just a ball, some bases, and nine men per side

Within five minutes of the final out—a Kenley Jensen strikeout of Christian Yelich—the stadium went dead quiet again, just like those green expanses did after the game’s original players picked up their bases and went home. There were no sounds of fans filing out, no clean-up crews sweeping the aisles. Just silence. Sudden and unsettling, yet comforting.