Bob Gibson Never Gave in. He Didn't Have to

He set basketball scoring records at Creighton. He hit 24 home runs and won nine Gold Gloves. He played for the Harlem Globetrotters. He won more games than any St. Louis Cardinals pitcher. He struck out more batters in a World Series game than anyone ever did. To borrow an overused phrase that in this case actually fits, he changed the game.

But when I think of the massively full life and career of Bob Gibson, I think first of 1968. It is not the 1.12 ERA that best defines him, nor the 17 strikeouts in World Series Game 1 against a Detroit Tigers team that never saw anything like him.

It is this: Bob Gibson threw 331 2/3 innings that year and never was removed from the mound in the middle of any of them.

Gibson started 37 times and finished 31 (including a 1-0 walk-off loss in 11 innings). He did not finish six games only because manager Red Schoendienst pinch hit for him with the Cardinals trailing by one or two runs after Gibby had given him seven, eight or 11 innings.

Never knocked from the box. Never gave in. Never knew any other way but to feed the furnace of ferocity within him to do whatever he could to win a ballgame. That was Bob Gibson.

Such was Gibson’s fire that it is hard to comprehend it has been stilled. Gone at 84, taken by pancreatic cancer, Gibson passed away one month after teammate Lou Brock at 81, six weeks after fellow pitching great Tom Seaver at 75, and six months after 1968 World Series rival Al Kaline at 85. Four first-ballot Hall of Famers, all from genera that are virtually extinct in how the game is played today.

Pete Rose called Gibson the greatest competitor of all the pitchers he faced. Billy Williams once said Gibson on the mound was “as serious as anybody you ever saw.” Joe Torre, who played with and against Gibson, marveled at the unvarnished verity of the man. “There was never any selling of Bob Gibson,” he said.

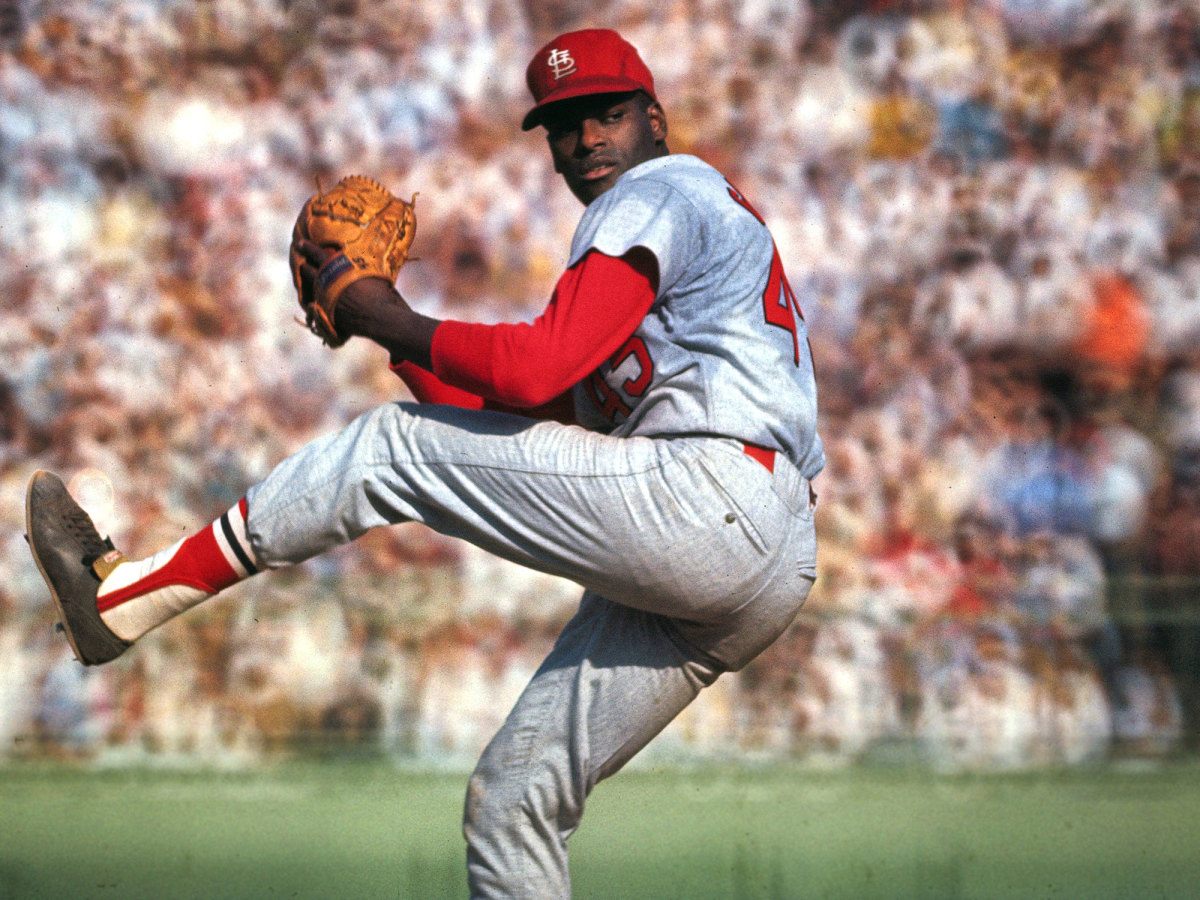

Gibson practically threw himself at the batter with every pitch. He launched his lithe, powerful body with such an explosion of speed and energy he shortened the distance his pitches had to travel. Such was the energy he spent that the lasting visual of Gibson is as much his follow-through as it is the actual throwing of the baseball, like a drag racer needing all that time and space to come to a stop. The intense physicality of Gibson in motion hinted at what was going on inside.

“One thing I’ve always been proud of,” he once said, “is the fact that I’ve never intentionally cheated anybody out of what they came to the ballpark to see. But most of all, I’m proud of the fact that whatever I did, I did it my way.”

He was an inveterate teller of the truth. He had no use for small talk. He did not suffer fools easily. He hated fraternizing. Gibson would leave All-Star Games early because he hated hanging around National League teammates who on any other day were his opponents. With pitches designed to reform hitters who dared look to pull his outside pitches, Gibson broke the collarbone of Jim Ray Hart, the elbow of Duke Snider and the bond with Bill White, his former roommate with the Cardinals who dared lean over the plate against him after a trade to the Phillies–in a spring training game.

Gibson fought for every inch he gained in this world from the very start. He was born in 1935 as the youngest of seven children raised by a single mother, a laundress, in a four-room shack in Omaha, Neb. His father died before he was born. After attending Creighton, he signed with both the Cardinals and the Globetrotters. But his stint with the Globetrotters did not last long, given that it was the sporting version of a casting error. As Gibson once said, he “hated that clowning around.”

With a baseball in his hand, Gibson tipped in his favor a world that conspired against a black man. There were no separate drinking fountains on the ballfield, as there were when Gibson made his way through the minors. The pitching mound had no separate quarters, the way teams had been holding spring training under Jim Crow laws in Florida. The Cardinals, led by White and Gibson, helped end such discrimination in 1961 by housing white and black ballplayers in the same St. Petersburg hotel. Gibson once wrote, “People would drive by to see the white and black families swimming together.”

Not vocal by nature, Gibson was nonetheless an agent of change. At 6-foot-1, Gibson always seemed so much taller, such was the evidential pride in his bearing. His pitching wasn’t just extraordinary. It was theatrical, mesmerizing in its intensity. To watch Bob Gibson pitch was to wonder how deep was the well of resolve from which it came.

In 1980 in a lovely New Yorker profile, White told Roger Angell this observation about his friend: “Any black player who has a sense of himself, who wants to make something of himself, has something of Bob Gibson’s attitude. Gibson had a chip on his shoulder out there–which was good.”

That drive may never have been as strong as it was in 1968, the Year of the Pitcher in baseball but also the year Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were gunned down. Gibson once said it seemed as if every pitch landed in its intended spot that year. He threw four-seamers with a natural cut, occasional two-seamers that dove into right-handed hitters when he needed a groundball double play, a curveball he would flip in for a free strike against left-handers, and a slider that was unlike anything most hitters had ever seen to that point. Baseball people used to call the slider a “nickel curve.” Gibson made such a term a farcical misnomer.

The pitch looked as angry as one of his fastballs but would break sharply and late, almost always away to right-handers and in to lefties. The way Gibson finished his delivery–falling toward the first-base side as if leaning into a sharp turn on a speeding motorcycle–gave the pitch its hellacious signature finish.

The Tigers had seen several great, hard-throwing pitchers that year: Luis Tiant, Sam McDowell, Tom Phoebus … MLB hitters batted just .237 that year. One out of every five games was a shutout. Detroit’s Denny McLain won 31 games. Offense and attendance were so down the owners voted after the season to lower the mound and shrink the strike zone. Hitters needed help because of pitchers like Gibson. More than anyone else, Gibson is synonymous with changing the game. The Tigers had no idea what they were in for.

These were days long before interleague play and cable television and video scouting reports. The other league might well have been another planet as far as familiarity was concerned. Gibson had beaten Boston three times with (of course) complete games in the 1967 World Series–mostly with his fastball–so he was not exactly an unknown. But to step in the box cold against Gibson was something entirely different. After the experience, which included the record 17 strikeouts in Game 1 of the '68 Fall Classic, the Tigers sounded like tourists who had just seen the redwoods in California, Niagara Falls or some other natural wonder to which all words seem inadequate.

“We weren’t surprised that he threw as hard as he did,” Kaline said, “but we were surprised his slider was so good. I think he’s one of the greatest pitchers I’ve ever faced.”

Said McLain, the losing pitcher, “That is the greatest pitching performance I’ve ever seen.”

“He hides the ball real well,” Jim Northrup said, “and it gets on you before you know it.”

Gibson threw 144 pitches that afternoon. The last was to Willie Horton, the last of the 17 strikeouts. Horton saw beyond Gibson’s stuff. He caught a glimpse of that furnace burning from within.

“What makes him great,” Horton said, “is that he never wastes a round. He is firing all the time. He works as hard on the pitcher as he does the cleanup man. Yeah, he’s tough all right.”

Gibson and the Cardinals would lose the series with a defeat in Game 7 in which Curt Flood misplayed a fly ball. Gibson was 32 at the time and a two-time World Series champion. It would be the last time he pitched in a postseason game.

Gibson started nine times in the postseason, all in the World Series. He was 7-2 with a 1.89 ERA, never leaving a decision to anybody else. He threw 81 out of a possible 82 innings. The only time he did not finish a World Series start was his first, in 1964, when manager Johnny Keane pinch hit for him with St. Louis trailing the Yankees, 4-1, in the bottom of the eighth inning.

Baseball rolls on. Like the Grand Canyon, it changes slowly over time. Complete games are nearly extinct. To compare the game today to 1968 is futile. The legacy of Bob Gibson is not bound within a statistic like the complete game. It is in the unparalleled fierce and seething need that drove him to throw every pitch with a purpose, and to not leave such work to someone else.

After Gibson’s 17-strikeout game, reporters huddled around Gibson in deep semicircle rings. Gibson had broken Sandy Koufax’s record of 15 strikeouts in a World Series game. Reporters come to these interviews with a narrative in mind. They think about the game from the outside in, not the inside out, which is to say from the exact opposite perspective of the athlete. The outside-in narrative in this case was that Gibson had shocked the world. He had overwhelmed the mighty Tigers. He had knocked the great Koufax from the record book. Naturally, a question was posed to Gibson to fit the narrative.

“Are you surprised what you just did?”

Replied Gibson, “I’m never surprised by anything I do.”

His answer, as Angell wrote, was met with “some ripples of disbelieving silence and (it seemed to me) a considerable, almost visual wave of dislike, or perhaps hatred.”

He had not given them the answer they wanted, the one that fit snugly into their narrative. They should have known it was classic Gibson, as if the baseball were still in his hands. Purposeful. Truthful.