Clayton Kershaw's Next Chapter

When Clayton Kershaw next takes the mound, he will do so as a different man. He has won the World Series. He has removed his name from the list of best players never to win a title. He has rewritten the narrative that surrounded him, the one that said he could not pitch in the postseason.

But that’s not what the people closest to him will notice. For the first time in more than a decade, he will be wearing a new glove.

In 2008, his rookie year, Kershaw used a glove with wide-set webbing. In ’09 he switched to the black Wilson A2000-CK22. (“As narcissistic as it sounds, I think it’s the Kershaw model,” he says.) He hasn’t pitched a game without it since.

That was the glove he raised in triumph through eight All-Star seasons, three Cy Young Awards, one MVP. It was also the glove he pounded in frustration every October, as one wretched inning spoiled most of his starts.

But he authored two of the best postseason games of his life in the World Series: six innings, one run in Game 1; 5 2/3 innings, two runs in Game 5. He decided that if the Dodgers finished off the Rays, he would get that ratty old Wilson framed. They did. So he will.

“It served its purpose,” he says.

So, in some ways, has he. When the Dodgers won their first pennant in 29 years, in 2017, an overcome Kershaw said he might retire if they won the World Series. Three years later, he finally won it.

He even found a benefit to baseball’s most unusual October setup: In response to the pandemic, MLB moved the postseason to neutral sites, and the Dodgers spent most of October in Arlington, Texas, just a few miles from Kershaw’s offseason home. He celebrated his crowning achievement in front of dozens of friends and family.

He gained everything he ever wanted for his career. But there is some loss, too. “As far as my profession goes, I only had one goal, and that was to win a World Series,” he says.

So, now what?

***

In the moments before Kershaw lifted the trophy, he struggled to figure out what to do with himself. He had spent Game 6 in the bullpen, manager Dave Roberts’s break-glass option in the event of extra innings. Kershaw found it easy to focus in the early frames, when the game was tight. But after right fielder Mookie Betts homered in the eighth to extend the Dodgers’ lead to 3–1, Kershaw knew they were on the cusp. He tossed a baseball at the wall. He pantomimed his delivery. He tucked in his shirt. He kicked at the rubber. He tucked his glove under his right arm and shuttled a ball from hand to hand. He sat down. He rocked forward. He rocked backward. He stood up.

“Just antsy,” he says now. “Just, hurry up and win this game!”

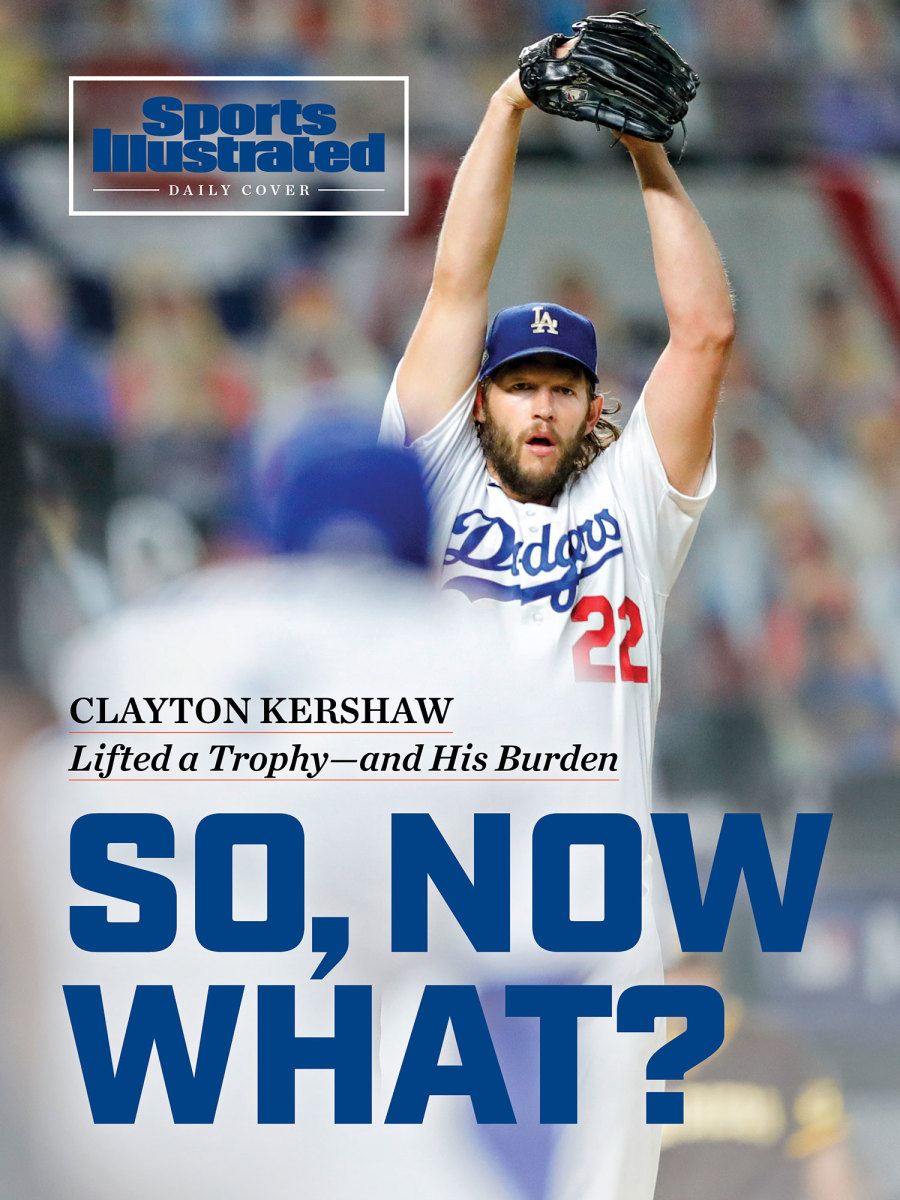

Then, at last, they did. As the final out zipped into catcher Austin Barnes’s glove, most of the Dodgers in the dugout and in the bullpen burst onto the field. Kershaw thrust his arms into the air, then took his time jogging toward the mound. In the days since, he has joked that that was his top speed. The truth is that he wanted to absorb the feeling flooding him. He was surprised to notice that it wasn’t joy. It was relief.

“The burden lifted,” he says. He had not fully realized it was there. He knew intellectually that he carried the weight of all those years, all those failures. But he did not understand until it was gone that it didn’t have to be there. “It just felt like normal life,” he says. “Like, that’s what you feel.”

By the time he was holding the trophy in his left arm and his 10-month-old son, Cooper, in his right, he had moved on to joy. But Kershaw’s favorite moment of the night is telling.

“After not succeeding in so many postseasons and having to look your teammates in the eye at the end of the season, you just feel terrible,” he says. Letting himself down was bad enough. He could not bear doing the same to the men who had sweated beside him.

“To be able to hug my teammates after that was probably one of the best parts of the whole thing,” he says. “Just to say thank you.”

Other than the hour or so they spent milling around the field in their new WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS gear, the Dodgers mostly missed out on the traditional trappings of the winner. There had been preparations for a champagne celebration and postgame party, but those were scrapped when third baseman Justin Turner’s positive COVID-19 test result came back in the seventh inning. The players were not allowed to invite their families into the clubhouse. They could not gather in large numbers back at the nearby Four Seasons, where they had been hunkered down since the Division Series. There was no alcohol-soaked flight home, no crowd of fans waiting at the airport, no parade.

Kershaw and a handful of others drained a few beers at the hotel, then went to bed around 4 a.m. He was up a few hours later to appear on the Today show. The Kershaws had packed up their Los Angeles house and sent their cars home to Dallas, so all that remained was to move out of the suite that had housed them for the past month. He and wife Ellen bundled five-year-old Cali, three-year-old Charley and baby Cooper into the car. Twenty minutes later, they were home.

***

Some people wake up the morning after they win their first title and feel empty. Kershaw grows more buoyed with each passing day. “I keep telling myself this,” he says. “We won a World Series in the city of L.A. after 32 years. It’s over. We did it. That's the feeling that I was always looking for, that feeling of, like, completion. We did it, and that's not to say we don't want to win next year, but just the fact that we did it this year, and it's over with, and we can actually just have normal expectations during the year will be awesome.”

He laughs now, remembering his emotions on that joyful night in 2017, when the Dodgers beat the Cubs in the NLCS, when Kershaw’s postseason narrative was a few chapters shorter. The 2017 Dodgers fell in seven games to the Astros, who later acknowledged having perpetrated a team-wide cheating scheme. In Game 5, Kershaw blew leads of four and then three runs. He threw 39 sliders. The Astros swung and missed at one. He did not retire.

People started talking more about what he hadn’t done than the fact he is the best pitcher of his generation. Some speculated he would never be dominant again. But this year, at 32, he produced a 2.16 ERA, his best mark in half a decade. For the first time in his career, Los Angeles did not ask him to pitch on short rest or as a reliever in the postseason.

He is not ready to retire, he says. He still loves baseball. He still feels good. He still wants to keep playing. “If it was this thing where I was just trudging along, I’d ride into the sunset, for sure,” he says. “I don’t feel that way at all.”

Kershaw has not yet begun his offseason training program. When he does, he will face a new challenge: He spent 32 years as one person. And now he is someone else.

“Every time I’ve pitched in the past, there’s all this stuff that goes along with me pitching, right?” he says. “All these things that people say. And I think that helped me a little bit, just the continued drive. Hey, I can't let up. I have to be perfect every time out. That might not be there anymore. I’m gonna have to create an edge. It might help me in the long run, just as far as not carrying that burden.”

Instead, he will carry a new one. He will have to unearth fresh sources of motivation. He will have to target additional goals. He will have to discover who he is now that he is a champion. And he will have to do it wearing a new glove.