The Hall of Fame Must Act With More Urgency–Before It's Too Late

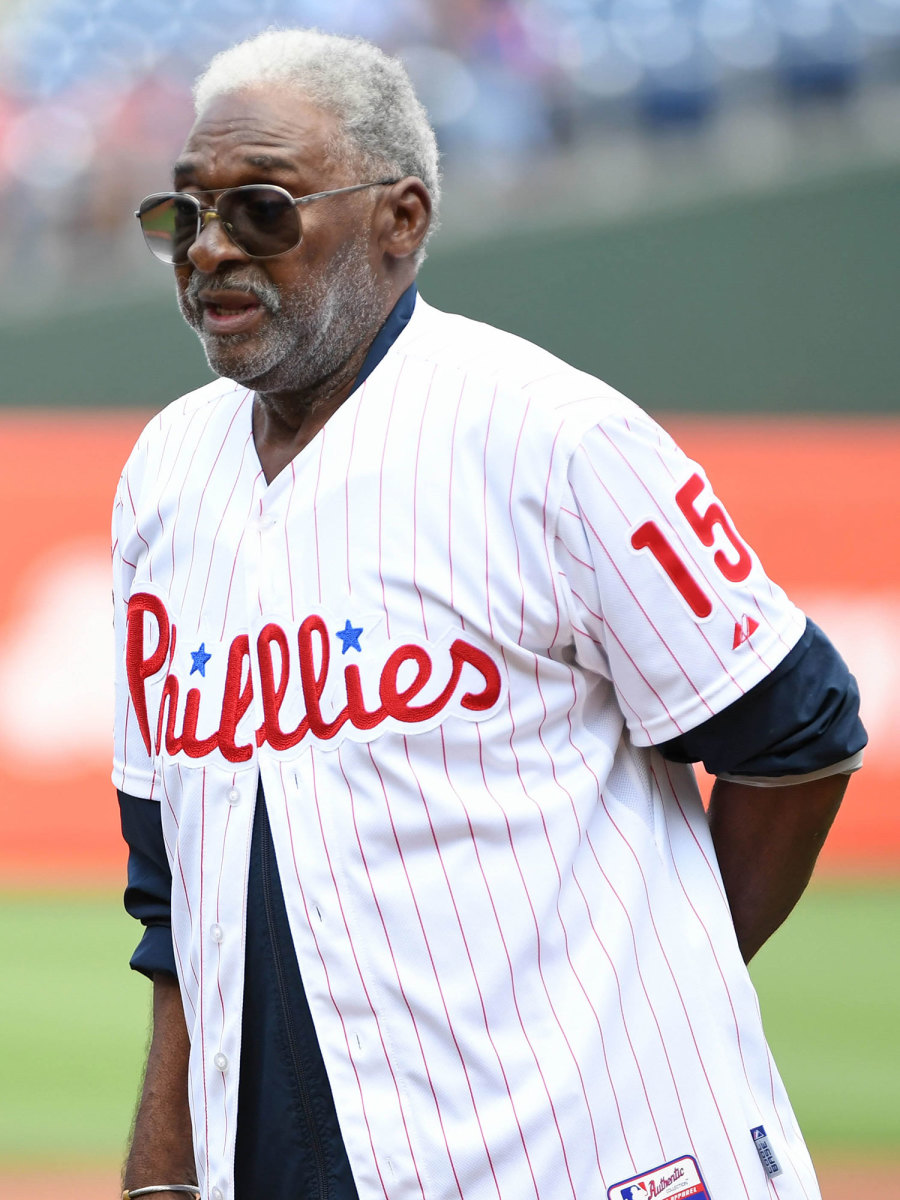

Dick Allen, who died Monday at 78, was, by adjusted OPS, the 19th-best hitter all time. He was a seven-time All-Star and the 1972 AL MVP. He may still be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, where he belongs. But he will never get to enjoy the honor.

That was Linda Santo’s first thought when she heard that Allen was gone. She remembered the moment nine years ago when the family got the call her dad had longed for: Ron Santo had been elected to the Hall of Fame. The news came a year and two days after his death.

“He really wanted it,” she says now. “It was important to him. It was that and a Cubs World Series. It was bittersweet that he was gone when both of those were achieved.”

Santo was a victim of the Hall’s thorny process: He became eligible for the writers’ ballot in 1980 but, perhaps in part because writers can vote for a maximum of 10 players each year, he received only 3.9% of the vote and fell off the ballot. The Hall gave him a second chance in ’85, and over the next 14 years his vote total grew but never made it to the required 75%. His next chance began in 2002, when the Veterans Committee began considering his case every two years. (The Veterans Committee votes in December for a class that will be inducted the following July.) That group elected exactly no one for three cycles, so the Hall revamped it. The ‘08 iteration did not elect anyone, either. Santo died in ‘10. In ‘11, yet another restructured committee met. This one elected him.

The Santos' celebration was not tinged with resentment, Linda says. They were just glad that the Hall got it right. But the family “fantasized” about how happy Ron would have been: pumping his fists, adding “HOF” to his autograph, beaming and backslapping at the induction ceremony each year. He yearned for those moments; he had joked over the years, “I better not get into this posthumously.”

Allen will likely suffer the same fate. He was one of the most feared sluggers of his era, but his rejection of the racism he faced as a Black man in Philadelphia meant that writers and opponents at the time labeled him a malcontent. Fans hurled so many projectiles at him that in 1966—a season in which he finished fourth in MVP voting—he began wearing a batting helmet even in the field.

Like Santo, Allen failed to clear 5% in his first year on the writers’ ballot, 1983. He received the same second chance in '85 but never surpassed 18.9% through his years on the ballot. After the four Veterans Committee shutouts, the Hall did not even include Allen on the 2011 ballot. He was back under consideration in ’14 … and he fell one vote short of election. One or two committee changes ago, he would have been on the ballot again for the ’16 or ’17 vote, but the Hall changed the process yet again: The new Golden Days Committee meets only every five years. That committee was scheduled to vote on Sunday, the day before Allen died. Instead of moving the meeting to Zoom, the Hall moved it to 2021.

“It was all about timing,” says Linda of her dad. She could be talking about Allen, too. It shouldn’t be that way. For an institution so aware of its place in history, the Baseball Hall of Fame sometimes seems not to understand its purpose. The Hall of Fame is a museum. But the plaques are awards. They aren’t really about fans; they’re about the honorees.

The Santos felt Ron’s presence at his induction ceremony. Every Little Leaguer they saw seemed to be wearing his No. 10; every clock seemed to read 10:10. The idea brought them comfort. But the Hall can make sure other families don’t need it.

The Hall should eliminate the 10-player maximum that often bumps borderline cases off the writers’ ballot and relegates them to the veterans committees. Twelve of the players on each of the 1980 and ’83 ballots (the ones Santo and Allen, respectively, fell off) eventually made the Hall of Fame. The writers literally could not vote for everyone who deserved to be enshrined.

The Hall should also show some urgency and convene more often the committees that consider the oldest living players. If they don’t make it, they don’t make it. But it’s just cruel to keep them out while they are alive and then induct them once they’re dead.

The Hall has not announced who will be on the 2021 Golden Days ballot, but joining Allen in the ‘14 voting were Tony Oliva, who is 82 years old; Jim Kaat, who is 82; Maury Wills, who is 88; and Luis Tiant, who is 80. Anyone who is not elected next December will have to wait until ‘26 to even be considered again.

“Can they find a process to put these older guys at the front of the line?” says Linda Santo. “I mean the ones who should’ve been in during the sportswriters’ [vote]. I’m not talking about, Oh, he was a nice guy. I’m talking about that group, and Dick and my dad were in that group: the guys who have the numbers and should be in. Why does it take so long? I don’t know.”

Allen may someday make it into the Hall of Fame. But he died thinking he hadn’t.