The Greatest (Forgotten) Game Ever Played: MLB's 1970 Exhibition to Honor MLK

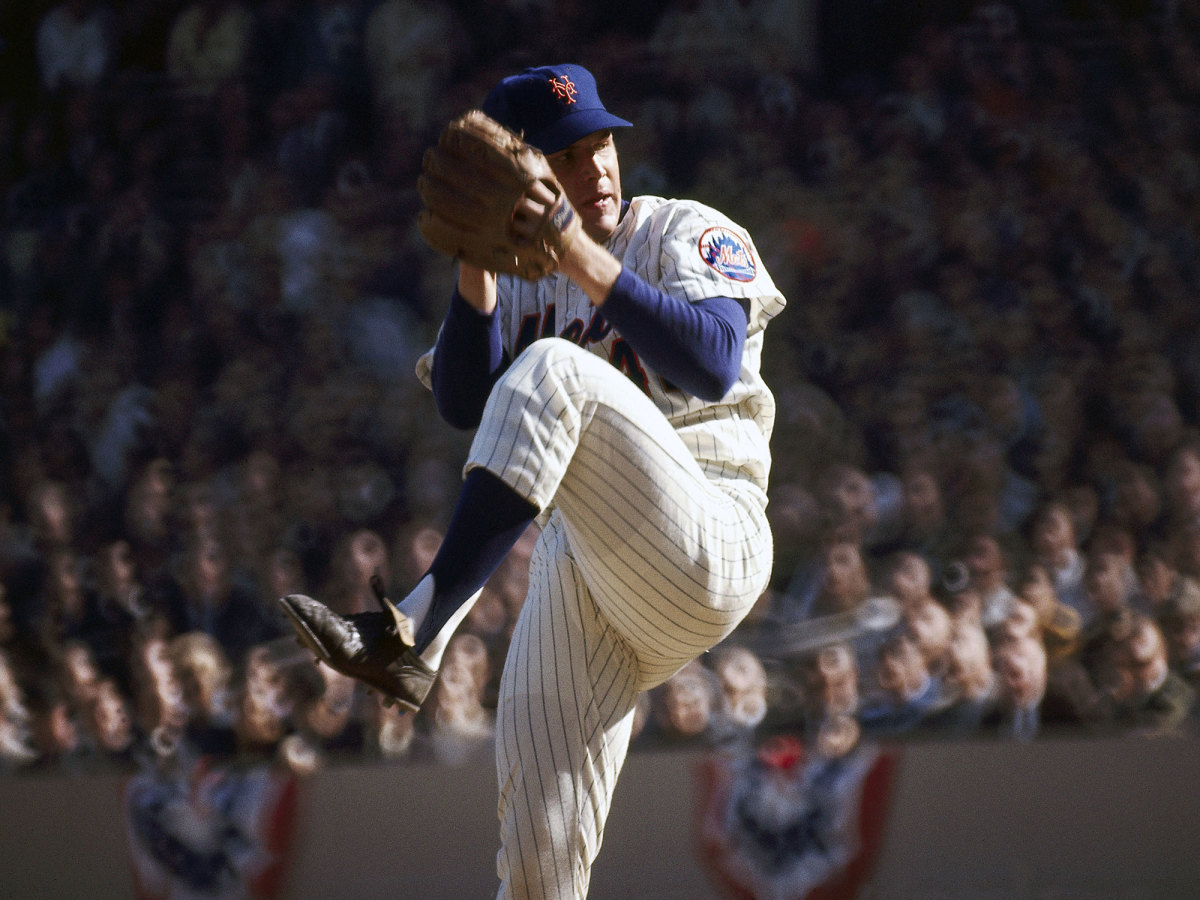

Manager Joe DiMaggio chose Tom Seaver as his starting pitcher, with Bob Gibson first out of his bullpen in relief. On DiMaggio’s bench sat Lou Brock, Roberto Clemente and Al Kaline.

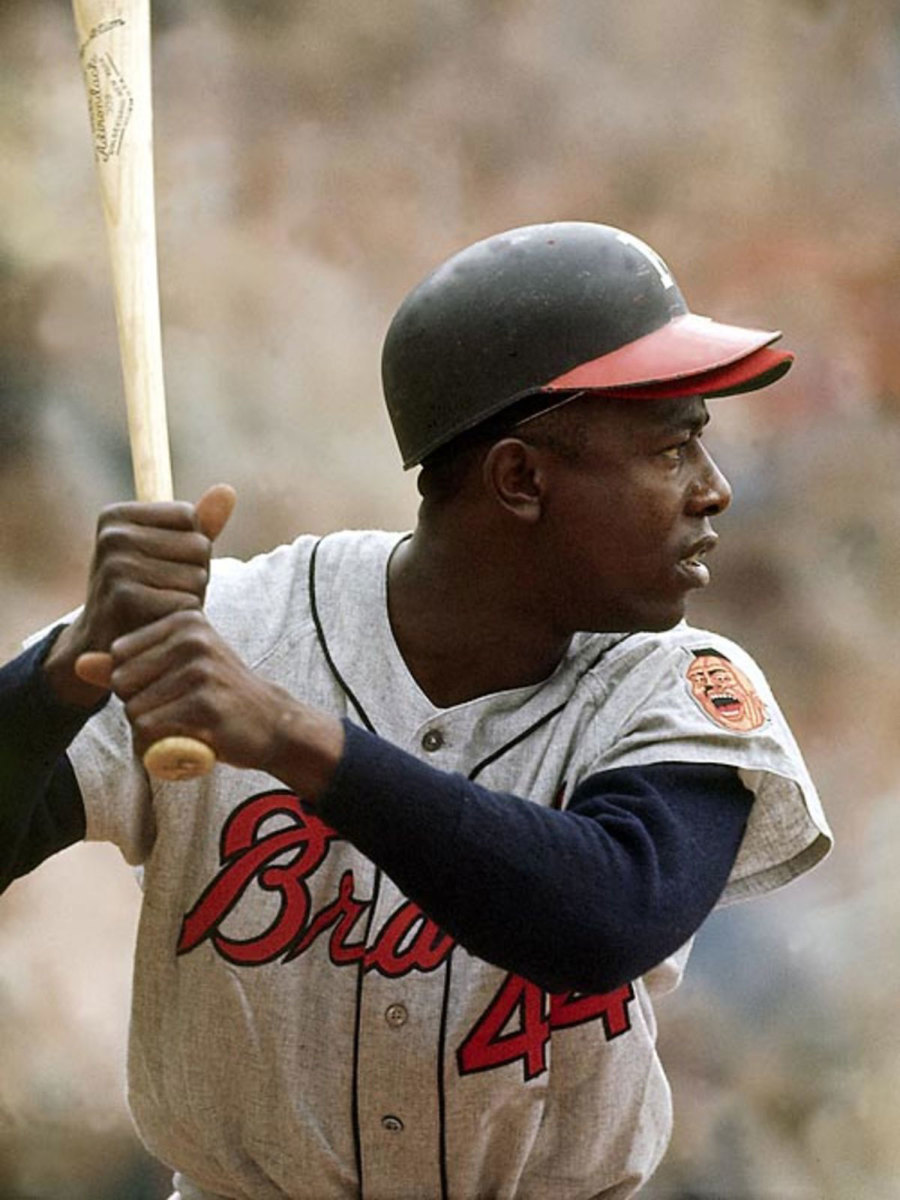

Roy Campanella, the opposing manager, filled the 2-3-4 spots in his batting order with Pete Rose, Hank Aaron and Reggie Jackson, his starting outfielders. Willie Mays flew 12,000 miles to take one at-bat off the bench.

Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Stan Musial, Satchel Paige and Larry Doby all were there in uniform. Jackie Robinson watched from the stands, as did Hollywood stars such as Sammy Davis Jr. and Danny Kaye.

It may sound like a dream, but it actually happened. What did happen at Dodger Stadium on March 28, 1970, may have faded into obscurity, in part because the game was played on a Saturday afternoon, in an almost half-empty ballpark, with no local television coverage while an amalgam of 18 local networks televised the game to little fanfare around the rest of the country. But when measured by the historic talent in uniform that day, and the reason why they played a baseball game, it may have been The Greatest (Forgotten) Game Ever Played.

At least 23 current and future Hall of Famers were in uniform that afternoon. Most of them left their spring training camps in Florida and Arizona for this one-game exhibition. Mays flew back and forth from Japan, where the San Francisco Giants were playing a series of exhibition games.

The players arranged the game to honor the memory and support the causes of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who had been assassinated almost two years ago to the day. All proceeds from the game went to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and to the construction of the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Atlanta.

“This is too important to pass up,” said Mays, who insisted on playing though he had been excused from the game on account of the Giants’ distant trip. “At last baseball players can show their feelings about the late Dr. King and his work through the medium of this game.”

It is not so unusual to see great gatherings of talent on one field. A 1917 benefit game at Fenway Park for the family of deceased sportswriter and former player Tim Murnane drew the likes of Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Shoeless Joe Jackson and Connie Mack. But the game was for whites only, as was the first All-Star Game in 1933, which featured 29 Hall of Famers (20 players, five coaches, two managers and two umpires).

The 1971 All-Star Game featured 26 Hall of Famers (including 21 inducted as players). But those rosters swelled with 61 players–15 more than at the more exclusive MLK game, known then as the East-West Major League Baseball Classic.

Including a pregame ceremony for the All-Century team, the 2000 All-Star Game showcased 33 Hall of Famers. Only 18 were in uniform.

The 1970 MLK tribute game occupies a unique place of greatness because it showcased not only many of the most important figures in baseball history, but also what can happen when Major League Baseball and its players work together for social good.

Players gladly volunteered their time. Seaver, for instance, fresh off throwing 295 1/3 innings for the world champion New York Mets, flew from Florida to Los Angeles to throw three innings in an exhibition game before flying right back across country.

“If Dr. King could give his life for a cause he believed in,” Seaver said, “the least I can do is give one day for it.”

Seaver grew up comfortably in Fresno, Calif. His father was a member of the U.S. Walker Cup golf team. Somebody asked Seaver if the issues important to King were alien to him.

“The issues were not at all alien,” Seaver said. “I respected him for treating violence with nonviolence. For making people ashamed, not angry.”

The Los Angeles Times noted the game featured a Black manager (Campanella), a Black starting pitcher (Earl Wilson) and a Black home-plate umpire (Emmett Ashford).

“A few years ago, it couldn’t have happened,” the Times wrote.

The idea of the game originated soon after King’s assassination and sprang from players who wanted to honor the civil rights leader. They contacted King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference for ideas on how to best do so. The SCLC suggested a benefit game. On Nov. 26, 1968, SCLC sports project director Joseph Peters wrote to baseball commissioner William “Spike” Eckert and the executive council outlining the players’ idea for such a game. Within a month reports surfaced that the game would be played March 29, 1969 in Los Angeles. Each of the 24 teams would send two players. Clubs would pay their travel expenses.

The time frame turned out to be too ambitious. The SCLC requested a one-year postponement.

“You can’t put the proper elements together in only 10 weeks,” Peters said, “especially since we want television revenue to be a large part of this fundraising memorial.”

The new date became March 28, 1970. It was formally announced one month in advance at a press conference in New York attended by Rev. Dr. Andrew Young of the SCLC and Bowie Kuhn, the new baseball commissioner.

“Baseball has shown that Black and white athletes can play together,” Young said. “The athletes’ identity with the nonviolence philosophy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference will tell something to the young people. Nonviolence is not characteristic of the weak. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

Players were selected by the Southern California Sportscasters Association and the Los Angeles chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America. DiMaggio and Campanella were named managers. The night before the game Bill Cosby hosted a reception for the players, staffs and dignitaries at Warner Brothers studio.

Only weeks earlier, DiMaggio, then 55 years old, had resigned from his dual roles as an executive vice president and coach for the Oakland A’s. He blamed increased business interests and a bad back, which was aggravated by air travel. DiMaggio hated night games and hated the coast-to-coast grind of the modern game.

Besides, he had just announced he was opening a restaurant chain to be called “Joe DiMaggio Italian Food.” The first one opened 12 days before the MLK tribute game–in Topeka, Kansas. Of course.

Asked to pick his coaching staff for the Los Angeles game, DiMaggio chose Billy Martin, who had just been fired by the Twins; Hank Bauer, a recent casualty from the A’s; John McNamara, Bauer’s replacement; and Paige. DiMaggio considered his managing gig for the MLK game a one-and-done affair.

“No, I never want to manage,” DiMaggio said. “Too much traveling. I can’t take it.”

Campanella looked at managing very differently. He always wanted to manage and still did. It would be another five years before a baseball team hired a Black manager, when the Cleveland Indians appointed Frank Robinson.

On March 28, 1970, Campanella put on his No. 39 Dodgers jersey for the first time since Sept. 29, 1957, his last game before an automobile accident four months later left him paralyzed from the waist down.

For his coaching staff Campanella chose Koufax, Drysdale, Musial, Elston Howard and Don Newcombe. At 2 p.m. Campanella wheeled himself to home plate at Dodger Stadium to exchange lineup cards with DiMaggio. The Yankee Clipper looking oddly garish in his white A’s cap and sleeveless jersey of Kelly green, Fort Knox gold and wedding gown white.

Campanella, manager for the West team, listed Maury Wills leading off in front of Rose, Aaron and Jackson, who only three days earlier had ended a month-long contract holdout. Jackson had been paid $20,000 in 1969 when he hit 47 homers with 118 RBI. He settled for $45,000 and free rent during the season in Oakland. At one point during the holdout A’s owner Charlie Finley told Jackson he could keep his offseason mustache as part of a potential deal. The Oakland Tribune reported in that case “Reggie would be the only major leaguer with a mustache” in 1970.

In a run of five straight future Hall of Famers in Campanella’s lineup, behind Aaron and Jackson were Johnny Bench, Orlando Cepeda and Joe Morgan. Sal Bando and Wilson hit eighth and ninth, respectively.

DiMaggio used Ron Fairly and Reggie Smith as his table-setters, followed by future Hall of Famers Frank Robinson, Willie Stargell, Ron Santo and 39-year-old Ernie Banks, who was so happy to be there he played shortstop for the first time in nine years. Mike Andrews, Tim McCarver and Seaver filled the bottom three spots.

A recording of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech played over the Dodger Stadium loudspeakers. Remarks were made by Rev. H.H. Brookins, president of SCLC West, SCLC president Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and by Kuhn.

Pitcher Mudcat Grant, described in news reports as “absolutely glittering” in a white tailored suit, sang The National Anthem from deep center field. King’s widow, Coretta, threw the ceremonial first pitch to Bench.

Tickets sold for as little as $2 for a bleacher seat and up to $10 for a box seat. Attendance was announced as 31,694. The game was blacked out in Los Angeles. In a last-minute deal, Channel 5 in Los Angeles acquired the rights to show the game the next day at 12:30 p.m. SCLC reported the proceeds from the game as $30,000.

The East won, 5-1. Seaver and Gibson shut out the West for six innings. Fairly, who was named MVP, and Santo hit home runs. In one eighth-inning sequence typical of the incredible star power–and diversity–Kaline singled, Brock doubled Kaline home, and Clemente doubled home Brock.

Details of the hits, runs and errors were unimportant compared to why the game was played. With Jackie Robinson watching, the game featured the first Blacks in MLB to umpire (Ashford), play in the American League and win a home run title (Doby); pitch in the World Series (Paige); play catcher (Campanella); win a strikeout title, 20 games and a Cy Young Award (Newcombe); win back-to-back MVPs (Banks), win the AL MVP (Howard); be named team captain (Mays); and win the Triple Crown (Robinson).

When the game was over, Banks beamed and said, “I’m ready to play another game, aren’t you?”

Said Santo, “This is the first game they’ve had like this and I’m really honored to have played in it.”

Campanella offered, “I thank these fellas for giving their time. I don’t feel bad about losing.”

Rose filed a column for the Cincinnati Enquirer in which he wrote, “I played a baseball game Saturday that meant an awful lot to me. It was more than just another game and even though it was an exhibition game it had meaning. In this game I felt I did some good for my country. I believe I’ve got to help any way I can and this is my way of doing it.”

Almost 51 years later, on Martin Luther King Day, the idea of what happened on March 28, 1970 seems so quaint and so simple as to be especially powerful. Think of it today: A bunch of sportscasters and sportswriters from Los Angeles pick two players from each team to play in an exhibition game. We’re talking about the best players. Future Hall of Famers. They will fly from their spring training locales to play one afternoon game in Los Angeles and fly back. They will not be paid. All proceeds help fight social and racial injustice. Nobody says no.

That warm afternoon at Dodger Stadium included men who not only changed baseball history but in trailblazing ways also changed the social arc of the country. But King himself knew the movement toward a more just and peaceful society relies on the smaller triumphs as well as the bold.

“If I cannot do great things,” he said, “I can do small things in a great way.”

Nearly faded from history, the 1970 game should be remembered as one of those small triumphs. The spirit of the game may best have been evident in first baseman Donn Clendenon, Seaver’s teammate with the Mets and on the East team. Born in Missouri, Clendenon was raised in Atlanta by his stepfather, Nish Williams, who played in the Negro Leagues. Young Donn received advice from Williams’s friends from the Negro Leagues, including Jackie Robinson, Paige, Campanella and Newcombe. Clendenon attended Morehouse College, where upperclassmen serve as mentors, or “big brothers,” to incoming freshmen. The man who volunteered to be Clendenon’s big brother happened to be a recent Morehouse graduate: Martin Luther King Jr.

Clendenon was not among the players initially invited to play in the MLK game. Seaver and Tommie Agee were selected from the Mets. But Clendenon was added to the East roster after Ken “Hawk” Harrelson suffered an injury. Clendenon vowed he would have been at the game even without Harrelson’s injury.

“Even if I have to hitch-hike,” he said. “I was a very close friend of Dr. King.”

Poetically, he added, “Weren’t we all?”