Will MLB's Best Hitters Recover From Their Awful 2020 Seasons?

The shortest season in baseball history was also the strangest for hitters. Two training camps, both abbreviated, four months apart. Only a few exhibition games, other than intrasquad scrimmages that don’t provide the edge-sharpening energy from playing an opponent in front of fans. Limited facilities and limited pregame work due to COVID-19 protocols. No in-game video. Little wonder that the average major league game last year saw fewer hits than any season except 1968 and the deadball years of 1907–09.

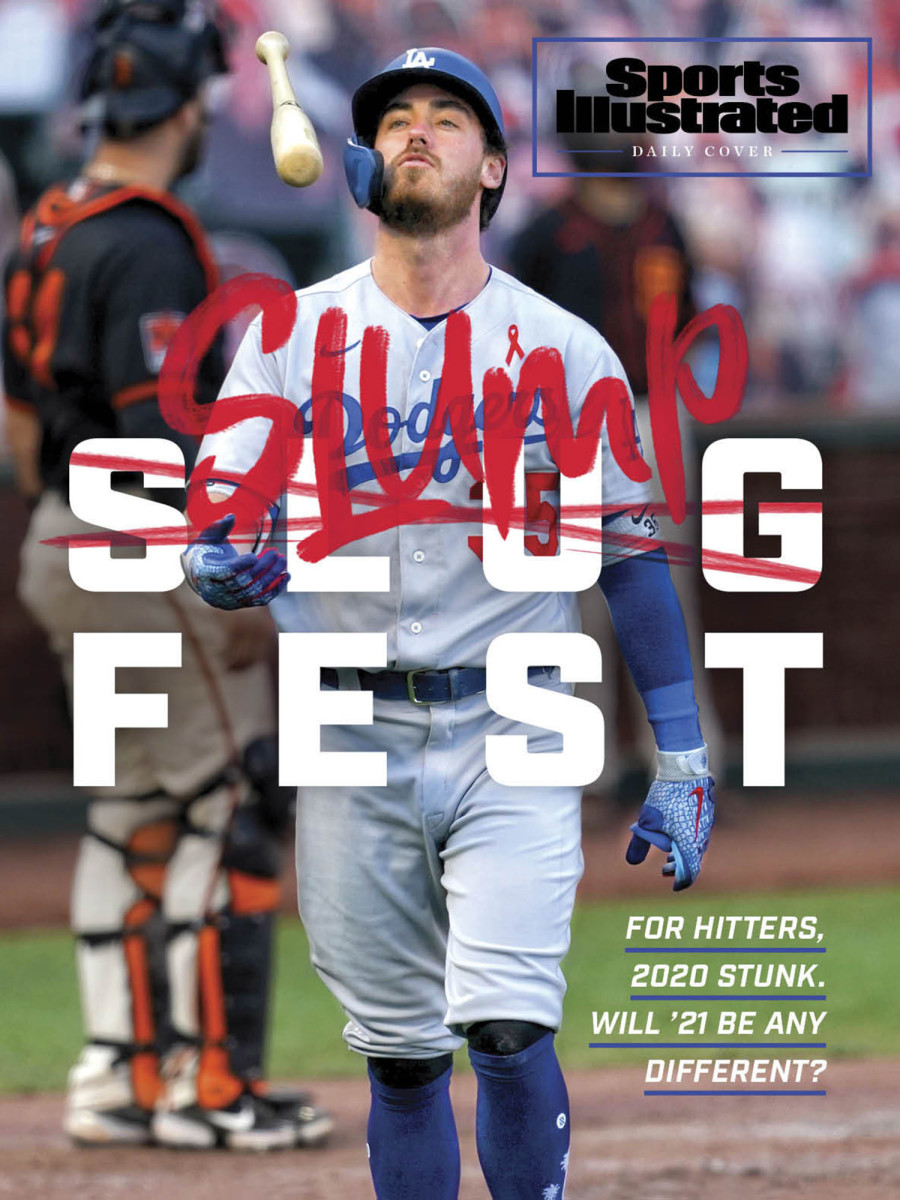

The story of 2020: When Great Hitters Go Bad. Among the 15 hitters who suffered the worst decline in slugging percentage, five of them won an MVP award or finished in the top four in the previous three seasons: Christian Yelich, Jose Altuvé, Cody Bellinger, Javier Báez and J.D. Martinez.

Other accomplished hitters who also looked strangely out of whack last year included Pete Alonso, Josh Bell, Alex Bregman, Kris Bryant, Keston Hiura, Austin Meadows, Yoán Moncada, Shohei Ohtani, Bryan Reynolds, Marcus Semien and Gleyber Torres—players who should be in their prime.

What should we make of great hitters having bad years? Do we write off the whole season as an anomaly? Do we see evidence for concern? The first place you have to start is with the odd rhythm of preparing for the season.

“The theme of last season across the league was just how important it is to have that preparation,” said Milwaukee Brewers hitting coach Andy Haines. “There is a certain rhythm to spring training. The size of those facilities can’t be taken for granted and the amount of what we can get done.

“To know [this year] we have these six or seven weeks is something we’re used to. We’re back in our element as far as preparation goes.”

Keep in mind, too, that with a short camp and bigger rosters last year, hitters saw more pitching changes, which makes hitting more difficult. Altuvé, for instance, took 41% of his at bats while facing a relief pitcher for the first time in that game—up from 35% the previous season and 30% from his first full season, 2012. Altuvé hit .154 last year in those at bats against a fresh bullpen arm.

Haines also noted that hitters pressed without the reassuring length of a 162-game season. Consider Altuvé again as an example. In the first 30 games of 2019, Altuvé hit .248. He still wound up hitting .298, close to his career average of .311. But when he hit .211 through the first 30 games of last season, he was halfway through the season. He did not have enough time to bob back up to his usual level. Deep down, hitters knew that. He finished at .219.

“Regardless of what guys will say and the magnitude of it,” Haines said, “the 60 games and trying to play catchup and knowing those at bats were running out on them, that played for the whole league. You could see it.

“I said it about a lot of hitters I was watching. They’re trying to have a good season with every swing they took. You could see it. And baseball cannot be played that way. It can’t. If the game ever sent us a reminder that it can’t be played that way, it sent us a pretty strong one in 2020.

“There’s just a threshold you have to play the game at. We all know what it means to try to do too much. Your heart’s in the right place, but things can break down. Your swing can break down; your ability to navigate an at bat can break down.”

Every flop is its own story. Understanding that sample sizes can be misleading, here is a look at what happened to seven premier hitters who went bad last year—and how confident their teams should be that they will bounce back this year.

Christian Yelich, Milwaukee Brewers (#1 in slugging decline, down -.241)

What went wrong: Yelich was too passive at the plate. In addition to having the biggest decline in slugging percentage last year, Yelich also saw the biggest decline in swing percentage, a drop from 45.2% to 34.6%. On pitches in the strike zone, Yelich’s swing percentage dropped 11.5%. Only Yandy Díaz and Jorge Soler turned more passive on pitches over the plate.

Likelihood of a bounce back: extremely high. When Yelich did swing, there was nothing wrong with his pop. His average exit velocity and the hard-hit rate actually improved. He also did suffer from the eighth-lowest rate on batting average on balls in play (-.096). He just needs to attack more.

“Christian, as we all know, wasn’t like himself in 2020,” Haines said. “Nothing’s automatic. What 2020 showed us is that nothing is automatic in this game. However, I don’t worry about Christian. I’m pretty excited to have him get a full spring training.

“He doesn’t need extra motivation. I know people may think there’s some there. But the way he’s made, he never lacks motivation anyway. He’s always pretty much on a mission.”

José Altuvé, Houston Astros (#2, -.206)

What went wrong: As the frequency of breaking pitches increases in the game, great fastball hitters such as Altuvé especially suffer. Altuvé saw 33.6% breaking pitches, up from 29.6% in 2019. His overall chase rate took the 14th biggest jump in MLB (30.0% to 35.2%). Fewer fastballs and more chase equals a down year. He will need to adjust. In the passive-aggressive game that pitching has become, cookie monsters such as Altuvé are getting fewer cookies to hit:

Altuvé vs. Fastballs in Zone Ahead in Count

Pct. | SLG | |

|---|---|---|

2019 | 24.8% | .640 |

2020 | 21.3% | .423 |

Likelihood of a bounce back: high. In a way, Altuvé already has bounced back. In the postseason last year he slashed .375/.500/.729. As long as Altuvé's legs are healthy, he’ll hit, even if he has to adjust to fewer cookies.

Cody Bellinger, Los Angeles Dodgers (#11, -.174)

What went wrong: Bellinger experimented his way into a slump. During the lockdown he fiddled with his setup to the point that the Dodgers hardly recognized him when summer camp opened. “He just got bored and started tinkering,” said one Dodger. He did return to his usual setup by Opening Day but never got his timing down during the 60-game season or even the postseason.

Bellinger has some of the best bat speed in baseball. He is an unusual hitter in that he does not make a first move until the pitcher releases the ball. But last year with just a small flaw in his timing, which delayed getting his barrel into the zone by a tick, Bellinger was beat often with fastballs—to the point where pitchers went against the industry trend and threw him more fastballs:

Bellinger vs. Fastballs

Pct. | Avg. | SLG | |

|---|---|---|---|

2019 | 52.7% | .333 | .670 |

2020 | 53.5% | .230 | .354 |

Likelihood of a bounce back: moderately high. His exit velocity fell by almost two miles per hour. Bellinger hit .200 vs. 95+ mph fastballs in the postseason, so he did not quite get back to his usual self even in the third month. Given his unique swing mechanics, Bellinger should accumulate more than his usual number of at bats in spring training games to make sure he gets his timing down.

Javier Báez, Chicago Cubs (#12, -.171)

What went wrong: It’s a more extreme version of what happened to Altuvé. Despite all the talk about velocity, spin is what is most suppressing offense. There is more of it, and that is bad news for Báez, who always hits off the fastball.

Fewest Fastballs in Strike Zone, 2020

1. Bryce Harper, Phillies: 16.9%

T2. Jose Altuvé, Astros: 21.3%

T2. Javier Báez, Cubs: 21.3%

Harper may see the fewest challenge fastballs, but he can compensate because he has a good eye and he hits breaking pitches well. Harper hit .250 against breaking stuff last year. But Altuvé (.135) and Báez (.157) have trouble with spin. Today’s spin-is-in game conspires against them.

Likelihood of a bounce back: moderate. People love to talk about Baez’s chase rate as the source of all evil, but he’s the rare hitter who can get his share of hits out of the zone. His chase rate actually went down last year. The problem was that his contact rate plummeted and, not coincidentally, he pulled the ball at his highest rate since his rookie season. Baez must improve how he reads and waits on breaking pitches.

J.D. Martinez, Boston Red Sox (#15, -.168)

What went wrong: A DH and hitting techno-geek, Martinez missed in-game video as much as any hitter. He did suffer a huge drop in BABIP (from .342 to .259), but that’s not so much due to bad luck as much as it is not hitting the ball hard. His exit velocity sunk from 91.4 mph to 89.5 mph, his worst mark since 2015.

As with Bellinger, it was very strange to see Martinez get beat continually with fastballs. The guy normally eats them for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Word got around last year to attack Martinez with more fastballs, an idea that had been unthinkable:

Martinez vs. Fastballs

Pct. | Avg. | SLG | |

|---|---|---|---|

2017 | 50.5% | .368 | .854 |

2018 | 52.4% | .370 | .716 |

2019 | 49.7% | .311 | .526 |

2020 | 53.3% | .173 | .327 |

Like Freddie Freeman, Martinez has long been a dangerous first-pitch fastball hitter. It’s partly because his stroke is so quick and partly because he’s so good at knowing when to expect one. But even that skill left him last year. (Though in fairness, he plastered such pitches at an EV of 97.6 mph.)

Martinez vs. First-Pitch Fastballs

Avg. | |

|---|---|

2017 | .485 |

2018 | .512 |

2019 | .450 |

2020 | .294 |

Likelihood of a bounce back: moderately high. Martinez will get his in-game video back. Players will have individual tablets in the dugout so they can view previous at bats from that game. (The video will not include views that show the catcher’s signs.) That alone will help Martinez, though he does turn 34 this season, an age when decline is common.

Gleyber Torres, New York Yankees (#16, -.167)

What went wrong: Yankees GM Brian Cashman said Torres did not return from the shutdown in his best shape. Torres needed almost a month to get on track—not a good idea when you have a two-month season. Through Aug. 12 Torres slashed .161/.277/.232. After that, once he began to pile up some reps, he looked more like his usual self: .300/.411/.463.

As with most young hitters who have early success, Torres also discovered that pitchers adjusted to him. Torres can turn around anybody’s fastball any time. But as breaking pitches gave him trouble last year (.162 average, .189 slugging), pitchers chose spin more often to put him away. He saw more of the classic Tampa Bay Rays style of pitching: Get strike one with a fastball; use your best breaking pitch to win the at bat.

Torres vs. Breaking Pitches When Behind in Count

Pct. | Avg. | SLG | |

|---|---|---|---|

2018 | 40.9% | .250 | .324 |

2019 | 38.7% | .226 | .398 |

2020 | 46.2% | .125 | .188 |

Likelihood of a bounce back: high. Torres’s run after the middle of August should have lessened any worry. Like Báez, he will have to adjust to seeing more spin, especially as put-away pitches. That adjustment starts not with hitting breaking pitches but recognizing them. He should remember this: 67% of all breaking pitches thrown when the hitter is behind in the count are not in the strike zone.

Pete Alonso, New York Mets (#55, -.093)

What went wrong: I included Alonso because this was the classic case of a hitter burying himself further after a slow start. (He would have been #25 at -.150 but for five hits, including three homers, in his final seven at bats.) The effort in Alonso’s swing was palpable. The harder he tried, the longer and later his swing became. The longer his swing became, the more he missed good pitches to hit.

Think of the fastball down the middle as the base pitch on which the swing works most efficiently and powerfully. The average major league hitter last season hit .343 and slugged .644 on fastballs down Broadway. Basically every hitter is Juan Soto if he gets a heater over the heart of the plate.

Not Alonso last year. The best evidence of how Alonso let frustration seep into his swing is seen right here:

Alonso vs. Fastballs Down the Middle

Avg. | SLG | HR | Fouls & Whiffs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2019 | .400 | .933 | 5 | 51% |

2020 | .154 | .462 | 1 | 59% |

Likelihood of a bounce back: high. With Francisco Lindor around, Alonso can stop trying to be all things to all people in Metsville. With his hands held low, he’s never been a great high fastball hitter (.193 last year, .216 career), but he should punish anything middle-down. A slow start won’t doom him. And these words from Haines might apply to Alonso as much as any hitter who struggled last year: “I think some guys will be better the rest of their careers because of what they experienced.”