Tragedy and Hope: An All-Time MLB Prospect, an All-Time MLB Scout and a Pop Fly

Money and a promise.

That is what Amada and Alfredo Edmead needed to allow their son to leave the Dominican Republic to play baseball in the U.S. in 1974. About to turn 18, Alfredo Jr. was a medical student at Santo Domingo Autonomous University, a school whose roots trace to 1538, making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the Americas.

El Tiburon took care of the money.

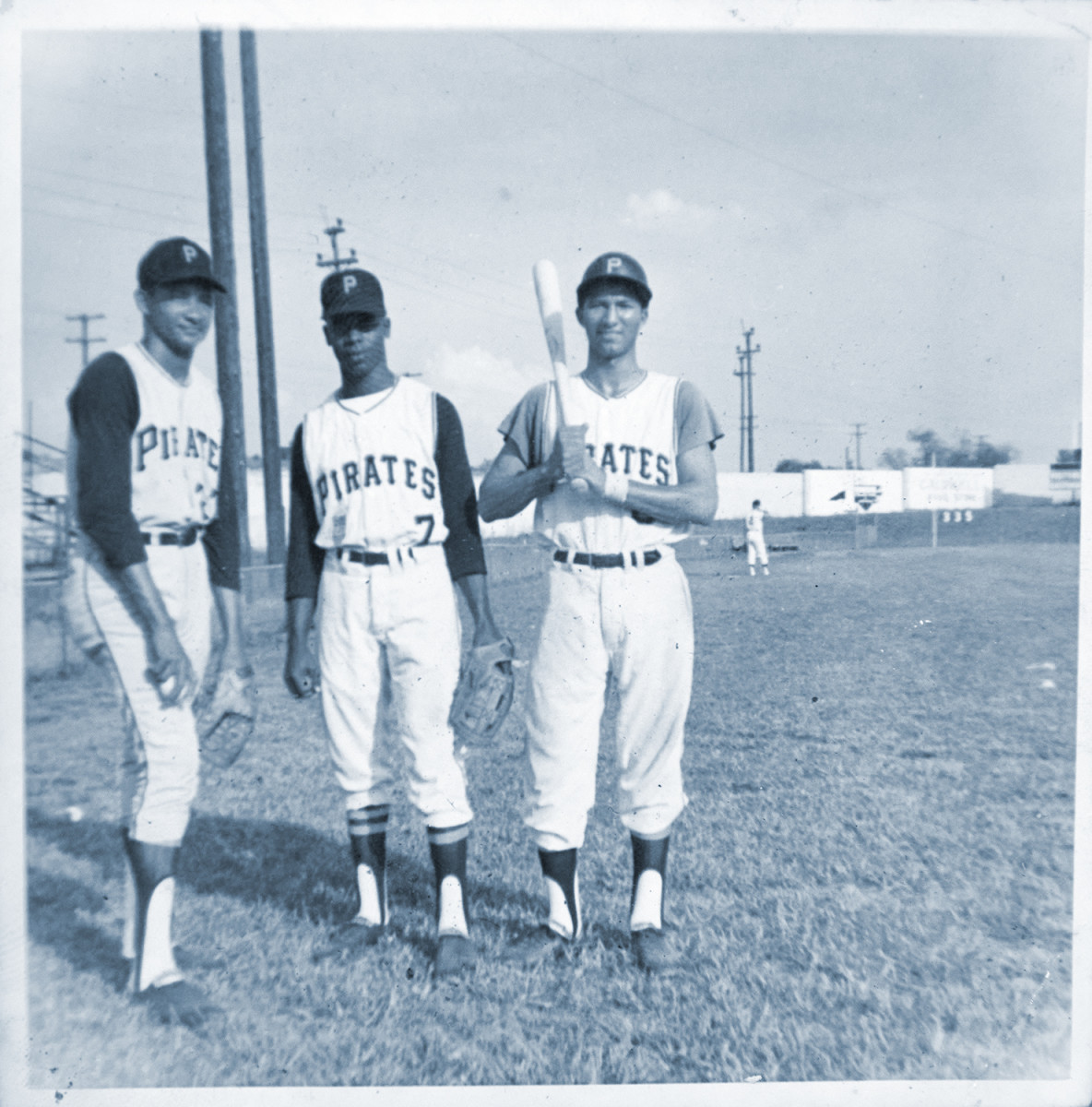

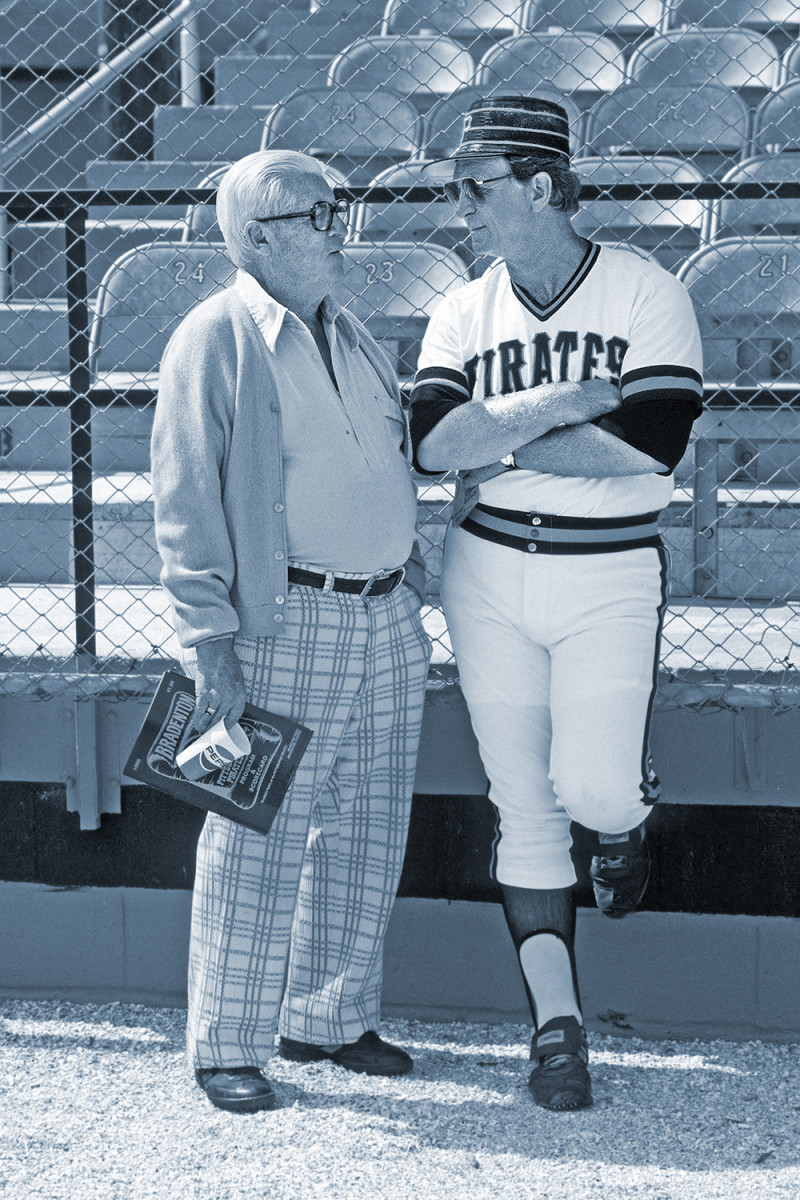

Howie Haak, then 62, was El Tiburon (The Shark), because of how relentlessly and stealthily he worked the far-flung towns of Latin America to sign ballplayers as a scout for the Pirates. The usually sun-scorched Haak bore a mien the color and consistency of worn leather, set off by a cumulus cloud of white hair and thick black sunglasses. Protruding from the sleeves of his guayabera were forearm tattoos, remnants of when he lied about his age (with his father’s support) to join the Navy in the 1930s. A pioneer of Latin American scouting, Haak held tryouts on some of the worst and most remote fields imaginable. He signed the few teenagers that passed his muster for between $100 and $500.

That pittance wasn’t going to work in the case of Alfredo Jr., who had showcased his talent in center field for the Dominican Republic all-star team in the Central American and Caribbean Games. So Haak offered $15,000, the largest bonus ever for a Latin American ballplayer at the time.

Haak, who died in 1999, at 87, would scout for almost 50 years. He saw thousands of players and discovered and identified scores of future big leaguers, including the great Roberto Clemente and such All-Stars as Manny Sanguillen and Tony Armas Sr. He once signed a pitcher out of a Mexican bordello, where the prospect lived with the madam. Among all those players over all those years in all those countries, one stood out to Haak as “the best prospect I ever saw”: Alfredo Edmead Jr.

Amada and Alfredo Sr. still needed a promise to allow Haak to sign their son. They needed reassurance that the Pirates would take good care of Alfredo. Pablo Cruz gave them that promise.

“I will look after him,” Cruz said. “I will keep him safe.”

Cruz, then 27, was a 10th-year Pirates minor league infielder who doubled as an apprentice scout to Haak—a bird dog for the bird dog in the Dominican. He lived in San Francisco de Macoris, about 130 miles north of the Edmeads’ middle-class neighborhood in San Pedro de Macoris. Cruz had been signed by Haak in 1965. At the time, only 16 Dominicans had reached the majors. The Pirates shipped him to their affiliate in Gastonia, N.C. Cruz spoke no English.

He never forgot the difficulty of making his way as an 18-year-old in a world of unfamiliar language and culture. That was one reason Cruz mentored young Latin players.

He also was the kind of selfless old soul who in the offseason ran a Little League program in the Dominican. He insisted the children switch-hit because he said without the nutritional and size advantages of those in the United States, they needed an edge to get ahead.

Cruz’s promise persuaded Amada and Alfredo. Their son signed for $15,000 with Pittsburgh. He was assigned to the Salem (Va.) Pirates of the full-season Class A Carolina League. To honor the promise made to the family, Pittsburgh also sent Cruz to Salem, even though he had spent the previous five years in Double A and Triple A.

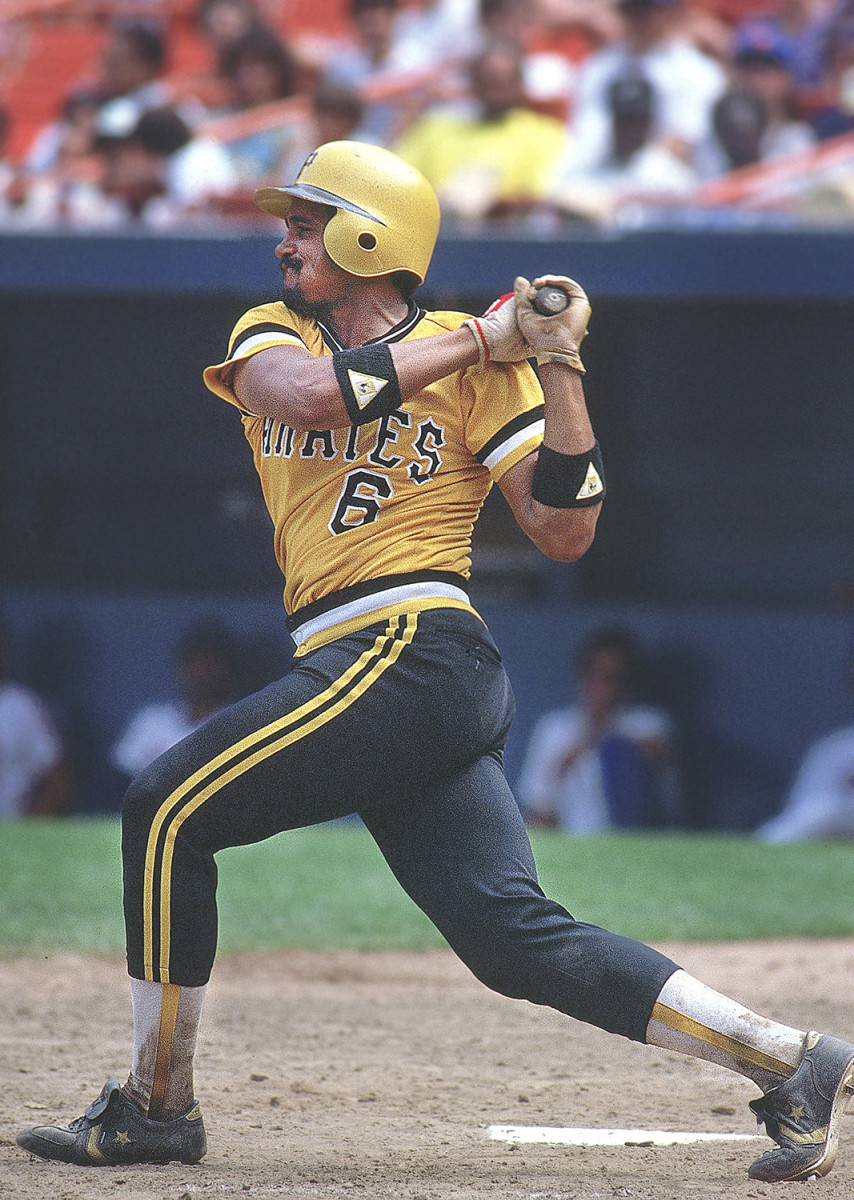

Pirates general manager Harding “Pete” Peterson called Edmead “the best young hitter in our farm system”—at a time when that included future big leaguers Armas, Miguel Diloné, Omar Moreno, Steve Nicosia, Ed Ott, Mitchell Page, Willie Randolph and Craig Reynolds. The youngest player on any Opening Day roster in the Carolina League, Edmead batted .314 and stole 61 bases. Scouts said that he was faster than Diloné, his teammate who stole 85, and that he had the team’s strongest arm in the outfield.

“There wasn’t anything that young man at 18 couldn’t do on a baseball field,” says former catcher Sal Butera, a Blue Jays scout who played for the Lynchburg (Va.) Twins that year. “He was probably the best player on the team, and he was very young. If he grew into his full potential, he would have been a major league All-Star for many, many years.”

On Aug. 19, 1974, with 10 days left in the season, Edmead was named to the Carolina League All-Star team. Around that time, he wrote a letter to Amada and Alfredo Sr. I am coming home August 31, it read. Prepare a great reception.

Their son came home in a coffin.

On Aug. 22, 1974, Edmead became the youngest professional ballplayer to die on a baseball field and remains such to this day. He died of a skull fracture and cerebral hemorrhage after colliding with a teammate in pursuit of a pop fly. As Edmead dived for the ball, his head smashed into the teammate’s knee.

The teammate was Pablo Cruz.

Grief is trauma to the soul that echoes. As the writer C.S. Lewis observed, misery bears a shadow: “the fact that you don’t merely suffer but have to keep thinking about the fact that you suffer. I not only live each endless day in grief, but live each day thinking about living each day in grief.”

Lewis wrote those words of angst in 1961, one year after his wife of four years died of cancer at 45. Edmead died almost five decades ago. That is a very long shadow.

“It still hurts,” Cruz says over the telephone in Spanish, with his son, Ismael, interpreting. “I pray for him every day. It’s been more than 40 years. People have respectfully asked me about that day. But I have not talked about it many times.”

Cruz is asked how he found the strength to carry on.

“Every time I would play second base, I would cry,” he says.

His voice trails off. There is silence. Then Ismael speaks.

“He has tears in his eyes right now.”

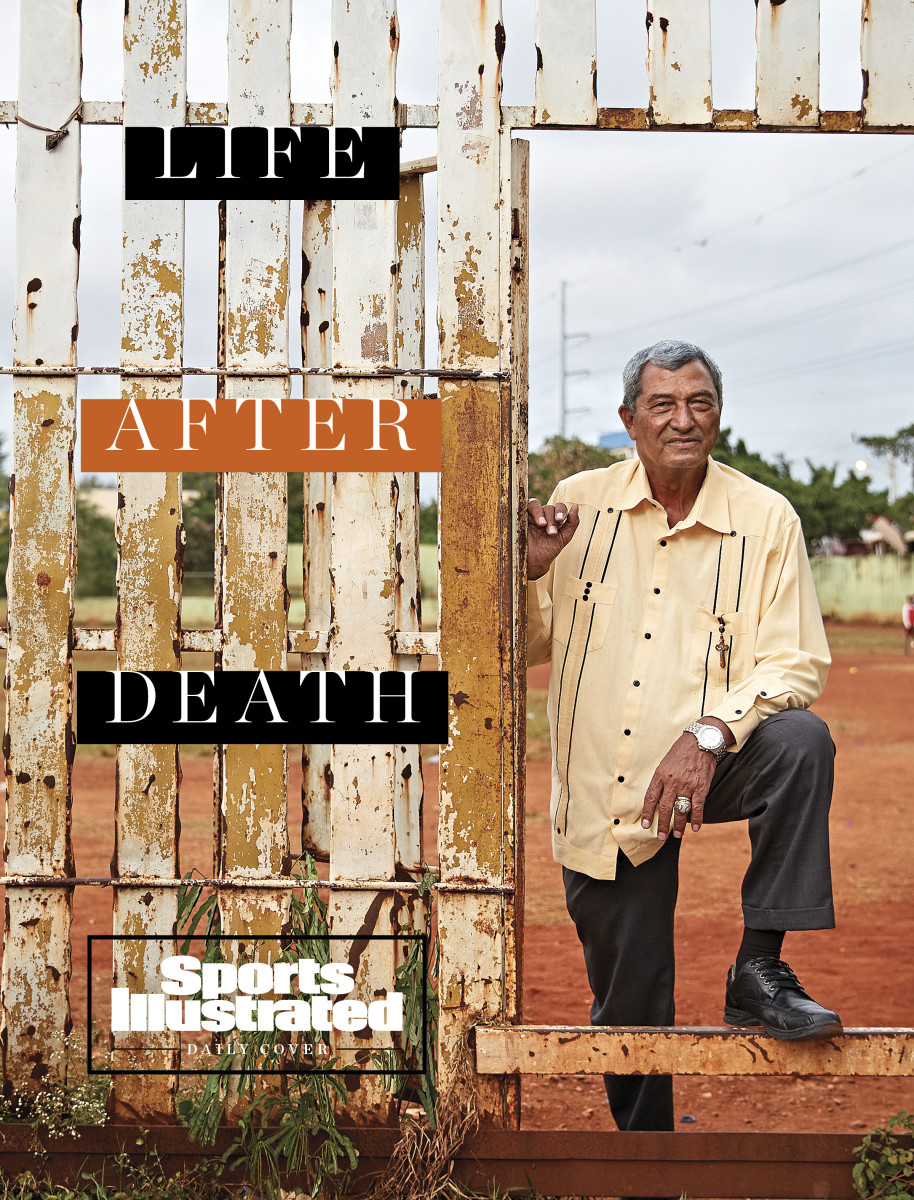

This is a story about life more than it is about death. It is a story of how grief not only wounds the soul but also can reveal it. Pablo Cruz did much more than carry on at second base. Now 74, he has given 56 years to baseball. He played eight positions in 1,480 minor league games over 14 years before dedicating himself full-time to scouting with the Pirates, Expos, Mets and Blue Jays as the heir to El Tiburon and as one of the most beloved and respected figures in the sport. He still scouts players in the Dominican, though now he may pass his findings to Ismael, who is the Dodgers’ vice president of international scouting, or to his grandsons, Brian Cruz, the Angels’ assistant director of international scouting, and Jonathan Cruz, the Braves’ manager of Latin America operations. Pablo is the patriarch of the first family of Latin American scouting.

Cruz also served as a hitting whisperer. His organization would summon him when a batter, especially one he had signed, was lost in the labyrinth that is a slump. Cruz inevitably would rescue the hitter. A deeply religious man, Cruz takes no credit. He says it was divine intervention.

“There are so many players that God has helped through me,” he says. “I’ve always asked for the Holy Spirit to be with me. I always feel that God is speaking to me. I preach the word of God everywhere I go.

“I’ve signed thousands of players. I probably signed the same amount that Howie did. How many got to the big leagues? About 50. If you count getting to the big leagues as an instructor or player, then more than a hundred.”

Asked the best part of his life in baseball, Cruz says, “I feel joy in seeing other people come up as a result of my work. And some guys continue to stay in baseball. This job has allowed me to work in baseball with young kids for 56 years.”

Therein lies the true story of Pablo Cruz. It is found not in the blood- and brain-stained outfield grass one horrible, warm summer night in the Shenandoah Valley but in the nearly 17,000 days that have followed. Cruz carried on and devoted himself not just to baseball but also to the dreamers within the game. More than just scouting, signing and instructing players, Cruz embraced them like family. Despite the grief, and guided by his belief in God, he never ran from who he was and what he set out to do.

“His impact?” asks Omar Minaya, the former GM of the Expos and Mets who counts himself among the thousands in the Pablo Cruz baseball tree. “It is as a person of high morals. A person who has mentored. A person who has given great opportunities to young players.

“From an ethical standpoint, there is nobody still standing like him.”

At the corner of Florida and Sixth in Salem, you can sit in the grandstand behind home plate with a view of the Blue Ridge Mountains and, as it has been ever since Municipal Field was built into the side of a hill in 1932, watch a baseball game or just daydream. When you watched Alfredo Edmead Jr. play there, you did both.

“Oh, my God. What a great player,” says Nicosia, the catcher on the 1974 Salem Pirates. “There was nothing he couldn’t do. He was a left-handed hitter who was as fast as lightning. Great outfielder. Great arm. Pop in his bat. Could hit for average and power. He was one of those rare five-tool guys.”

“A star of the future,” says Tom Prazych, the Salem first baseman.

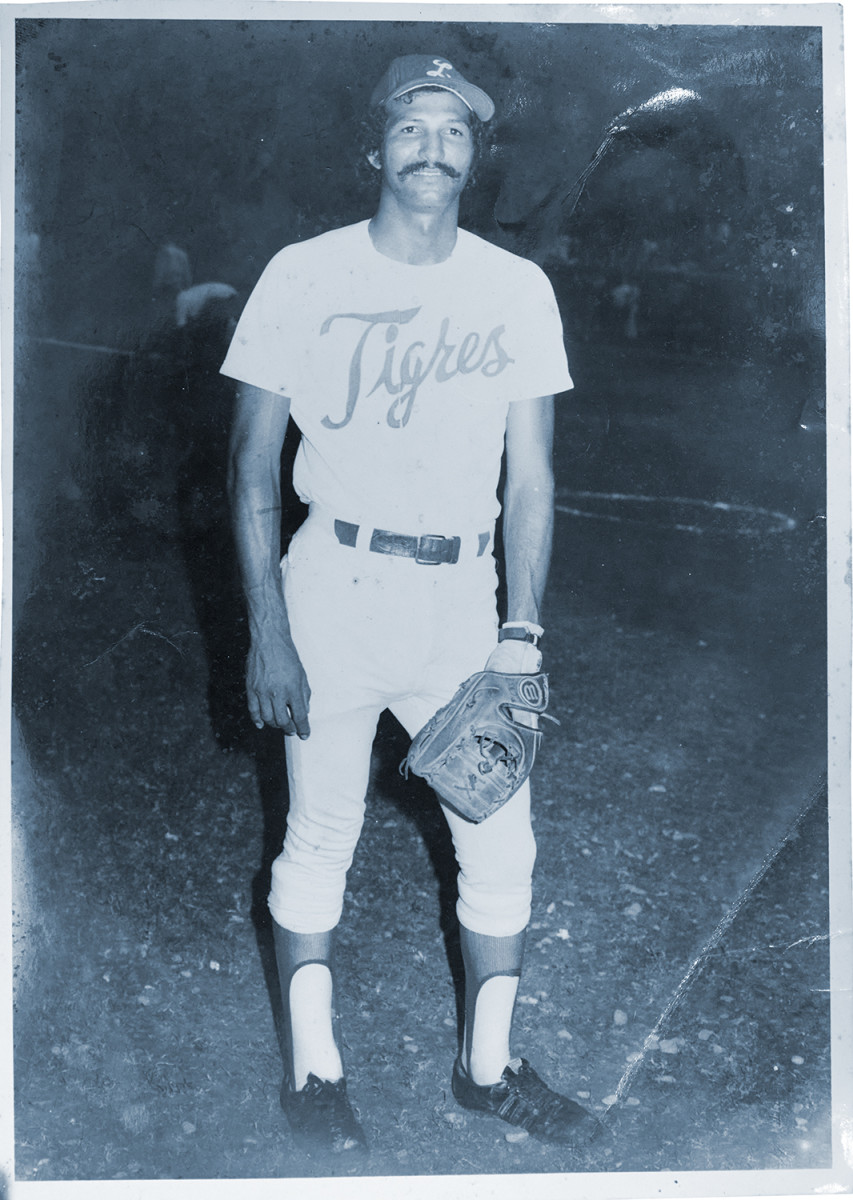

Edmead was wiry, strong, 6' 1" and 154 pounds. Handsome, with the long sideburns that were fashionable in the mid-1970s, he played baseball with grace, beauty and ease that defied the difficult nature of the game. He was the rare first-year pro who skipped rookie ball.

Peterson, who had been in Pittsburgh’s front office since 1969, said at the time, “We never had a rookie tear up the Carolina League like this, except Art Howe, and he was 24 then.”

Edmead lived with Diloné, an outfielder and fellow Dominican, who was known as Seata Cibaena (Cibao Dart) for his tremendous speed, and followed him atop the Salem lineup. In 137 games that season they combined for 322 hits and 146 stolen bases. The Sporting News referred to them as the Dominican Duo. In a rare reference to the lower minors, New York Daily News columnist Dick Young, the most influential sportswriter in the country, wrote in June how Diloné and Edmead “can come close to 100 stolen bases this year . . . that’s each.”

Edmead met and quickly became serious with a girl from Andrew Lewis High, whose football team also played at Municipal, which explained the football scoreboard on the first base side. Salem, a town of 22,000 residents, 14 ½ square miles and a Main Street straight out of 1950s Hollywood with its red brick buildings and church steeples, treated its Pirates minor leaguers like family visiting for the summer.

“No matter where we went, we could get a meal for a couple of dollars,” Nicosia says. “Everything was geared around the team.”

Six players from the 1974 club reached the big leagues: Nicosia, outfielders Diloné and Page, and pitchers John Candelaria, Rick Langford and Greg Erardi. The manager was Johnny Lipon, then 51, a former major league shortstop who managed 30 years in 17 towns for Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

“His wife had passed and his children were grown,” Nicosia recalls. “We were basically his kids.”

The general manager was Dan Kinder, who was just two years out of Princeton. The son of a lawyer, he grew up in St. Clairsville, Ohio, as a Pirates fan. When he watched Edmead, Kinder was reminded of Clemente, who had died fewer than two years earlier in a plane crash. He saw Edmead attack the game with the same passion.

“He was very, very intelligent,” Kinder said of Edmead in that summer of 1974. “I went to Princeton, and 75% of the people there didn’t have minds as good as his. . . . His interests were broad, from religion to art to music to theater.”

When Edmead wrote to his parents in August to say he was returning home at the end of the month—Prepare a celebration—his first season abroad and in pro ball was in every way imaginable a wonderful success. It was a promising beginning to what Amada and Alfredo Sr. described as his twin dreams: to be a major leaguer and “to be a source of pride for his country.”

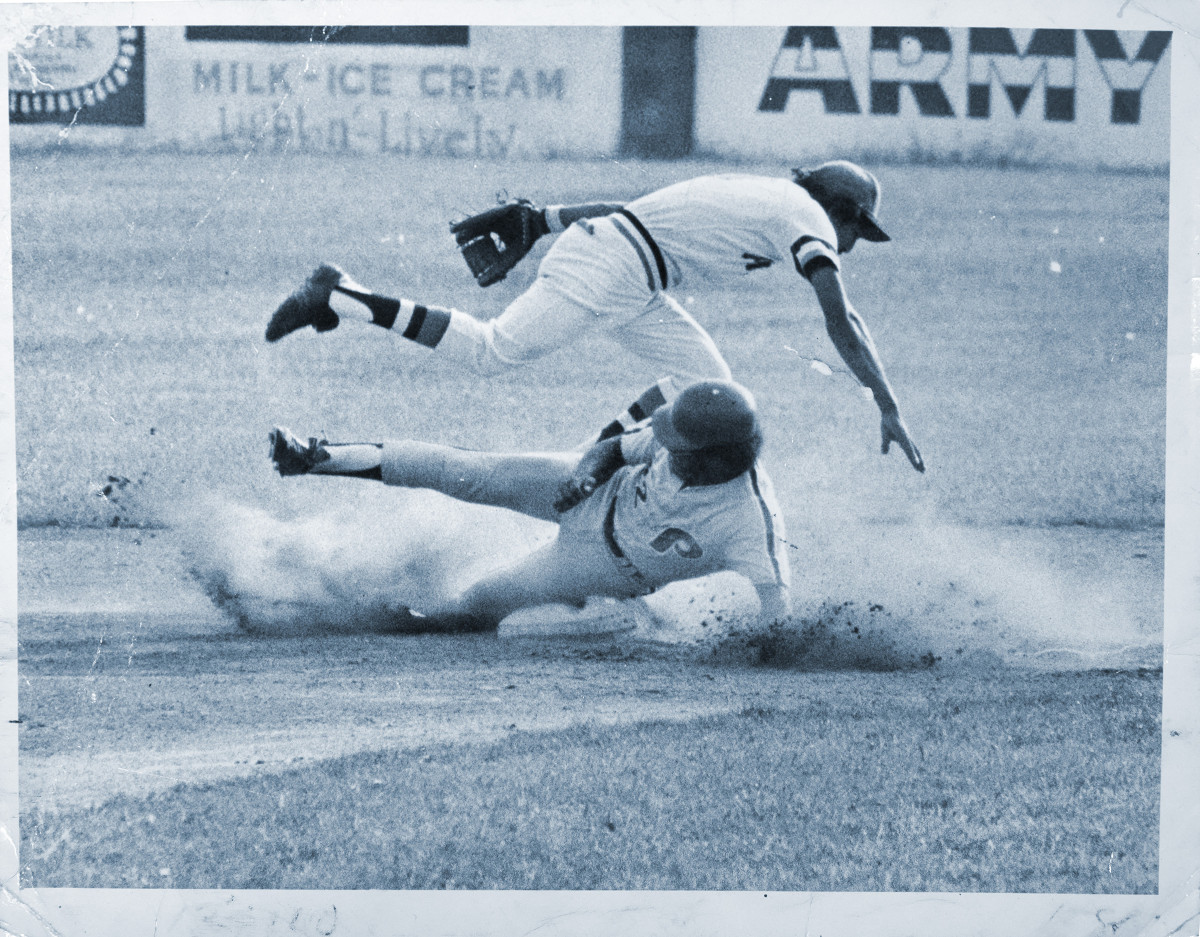

So sweet was the joy of that summer—and the possibilities of the many lush summers that lay in front of him—that any of the 937 fans at Municipal Field on the evening of Aug. 22, 1974, could see it glow upon his face. Playing that night against the Rocky Mount (N.C.) Phillies, Edmead singled in the bottom of the first inning, then swiped second and third on consecutive pitches. Each time, as United Press International reported, Edmead bounced up from his slide with a grin on his face.

Five innings later, Phillies pitcher Murray Gage-Cole, batting against Candelaria, hit a pop fly.

Pablo Cruz was voted the most popular player on the 1974 Salem Pirates.

“He could have run for mayor,” says Murray Cook, who grew up so close to Municipal Field that well-struck fly balls hit his house. Cook was 14 in the summer of 1974. For $3 a game, plus a hot dog and a Coke, he served as the team’s ball boy, batboy, foul-ball shagger (“Twenty-five cents a ball”) and press box attendant.

“Everybody loved Pablo,” Cook recalls. “He hustled, he played the game the right way, he signed tons of autographs, he loved the kids who would hang around the ballpark. . . . They were always asking me for cracked bats. The ones they wanted were Pablo’s bats. He was Salem’s Willie Stargell.”

One of 14 children, Cruz was born on a vegetable and sugarcane farm and subsequently moved to the city of San Francisco de Macoris, known as Tierra de Cacao for its world-leading production of organic cocoa. “I always prayed to God that I would play for the Pirates,” he says.

One day in 1964, El Tiburon ventured into Tierra de Cacao to see whether he might find any ballplayers. Haak held a tryout for 300. He offered contracts to three. One agreed to one of Haak’s meager signing bonuses: Pablo Cruz.

“It was like a child’s dream come true,” Cruz says.

A middle infielder and contact hitter with a strong arm, Cruz climbed Pittsburgh’s organizational ladder rung by rung until reaching Triple A in his sixth year. He would go no further. But the Pirates and Haak took note of his equanimity and baseball intelligence. They deputized him as a scouting assistant to Haak while he was still playing in the minors.

“Howie was like a father to me in baseball,” Cruz says. “He helped me all the time when I first started scouting. He would look for speed, arm and swing. Howie wasn’t scared to go places where all the U.S. guys wouldn’t go. He would go to any city any other scout wouldn’t go to. Anywhere in Latin America.”

Cruz learned from Haak. Haak had learned from Branch Rickey, the executive best known for signing Jackie Robinson in 1947. The Mahatma hired Haak in ’39 as a trainer and coach with the Rochester (N.Y.) Red Wings, one of 28 minor league affiliates in his famed Cardinals farm system. When Rickey called up Stan Musial from Rochester to St. Louis in ’41, he consulted Haak first.

Rickey took Haak along with him when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1942 and again when he joined Pittsburgh in ’50. In between, from ’42 to ’46, Haak served in World War II, attaining the rank of lieutenant commander.

Late in the 1954 season, Rickey sent Haak on a scouting mission. He told him to scout the Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s affiliate in the Triple A International League. Rickey knew the Dodgers were loaded with talent, and he would not mind picking the pocket of his former club in the Rule 5 draft, when eligible nonrostered prospects can be selected from other organizations.

Haak snooped around. A Royals pitcher, Glenn Mickens, told him the youngest player on the team also was the best prospect in baseball, but “they won’t let him play.” The Dodgers were hiding draft-eligible Clemente, then 19, from other clubs. Haak watched the Royals for a month and saw Clemente take only four at bats. On Nov. 22, 1954, on the advice of Haak, the Pirates drafted Clemente. The young outfielder from Puerto Rico told Rickey, “There is plenty more talent down there in the Caribbean.”

Rickey in turn told Haak, “Go find if there are any more like him.”

The Caribbean pipeline began to open. El Tiburon became so famous on the scouting circuit that he acquired two other nicknames. His rivals called him the King of the Caribbean. The young Latin American players called him Big Daddy. Haak not only signed Cruz but he also tutored him in scouting.

“We are all in the same family: the baseball philosophy of Branch Rickey,” Minaya says. “Pablo is another disciple. I hired Pablo in Montreal and with the Mets. People like talking to me about [two-time Cy Young winner Jacob] deGrom. We drafted deGrom in the ninth round because we applied the Branch Rickey philosophy of ‘get athletic players.’ deGrom was a shortstop. We had one report on him. Pablo saw the video. Because of Pablo and the Rickey theory of acquiring athletes, we drafted him.

“Once in Montreal, I drafted Ian Desmond in the third round. I did it because I said, ‘Pablo, go see him.’ He did and recommended him. When it comes to evaluations, his are the cream of the crop.”

The 1974 Salem Pirates were a dominant team from the start. They won 9–1 on Opening Day. Diloné and Edmead combined for four hits and four runs. Cruz was not in the starting lineup. He had undergone offseason surgery on his left knee and needed a few more days to recover. He returned wearing a metal brace. Lipon mostly batted Cruz third, behind Diloné and Edmead. In the same order, the three Dominicans finished 2-3-4 in the Carolina League in hitting. Along with Nicosia and Candelaria, all were signed by Haak.

Stocked with Haak’s finds, the team led the league in runs, homers, stolen bases and batting average. Its pitchers led the league in ERA and strikeouts.

“Wow,” Cook says, “it was a tremendous team. And it was a very close-knit team.”

“When you are young and in the minor leagues, all you have is each other,” says Nicosia. “Between the bus rides and hanging out at the ballpark, we all became very close. We were like a family. Diloné barely spoke English, but it didn’t matter. It didn’t matter whether you were Black or white or Spanish-speaking, from L.A. or Miami or the Dominican. Everybody got along. We became friends.”

Cruz, because of his age and wisdom, played a special role. “He was the old man of the gang,” Nicosia says. “I don’t even think we had an assistant coach. Pablo was like an assistant to Johnny Lipon. He was like our senior mentor. . . . We had a lot of Spanish-speaking guys and he was like a father to them.”

Cruz was an actual father, too. He and his wife, Josephina, had three children under age four, all of whom were born Oct. 3. “That made it easy—one cake,” he says.

Cruz, 5' 11" and 158 pounds, was playing second base on the night of Aug. 22. He still had the brace on his left knee. As a 27-year-old in Class A ball, Cruz kept hope alive of playing in the majors but knew his future was as a scout. He wanted not just to scout players but also, like El Tiburon, and as he was with Edmead, to be their big daddy.

And then a pop fly went in the air.

The loss of loved ones leaves a heart forever broken.

“But this,” the writer Anne Lamott observed, “is also the good news. They live forever in your broken heart that doesn’t seal back up. And you pull through. It’s like having a broken leg that never heals perfectly—that still hurts when the weather gets cold, but you learn to dance with the limp.”

Cruz played four more seasons at Salem, the last in 1978, when he was 31. In ’76 he was named to the Carolina League All-Star Game but skipped it to fly back home and attend his parents’ 50th wedding anniversary. In ’77 he played with Tony Peña, the future five-time All-Star catcher whom Cruz signed out of the Dominican two years earlier. Cruz hit a career-best .341, second in the league, and did not get promoted.

“I thought they would let me go up one more time, but now I’m happy they didn’t assign me to Double A,” he said then. “In Salem people are good. If I can’t go to the big leagues, I prefer to stay here all my life.”

After that season, Haak bequeathed his Latin America scouting territory to Cruz. In addition to Peña, Cruz signed Moises Alou, Rafael Belliard, Aramis Ramírez, Pascual Pérez, Jose Guillen, José De León and several other future big leaguers. According to the 1997 Pirates’ media guide, Cruz was responsible for signing 20% of the players in their farm system (37 of 180). He also provided hitting instruction on an on-call basis.

In May 1986, Peña was hitting .216 with one home run when he called Cruz and asked him to join the team in Houston. “I told him I couldn’t,” Cruz says, because club executives required him to get clearance before coaching a batter. “I told Tony to go to the GM and ask for permission. And they gave me three days to work with Tony. I left the Dominican and prayed to God to help me out.”

Cruz met Peña at the team hotel. The first thing they did was find a church, where they asked God to, as Cruz said, “help make his heart light.”

“Tony felt that God visited him that night,” Cruz says. “After that, everybody knows the history.”

Peña had two hits in his first game after his three-day visit with Cruz. He hit .308 over the rest of the season.

In 1984, three years after he gave Cruz his territory, Haak had been honored with the inaugural Scout of the Year Award. Thirty-two years later, Cruz won the Scout of the Year Award, one of only seven international scouts so chosen.

“There is not a player who doesn’t see him as a father figure,” Blue Jays general manager Ross Atkins said then. “I can’t imagine a better compliment.”

The pop fly is the most mundane of at-bat outcomes: 96.9% of major league pop-ups are caught. It is so routine there is a rule that in some cases declares the batter out while the ball is in the air.

On Aug. 22, Gage-Cole skied a Texas League pop fly. Cruz, first baseman Prazych, center fielder Diloné and Edmead, in right, all started toward it. Prazych and Diloné realized it was beyond their reach and slowed to a stop. Cruz was running into the outfield with his eyes on the baseball to make an over-the-shoulder catch. Edmead was sprinting in.

A 16-year-old local named Don Reid watched from the stands along the third base line.

“It was a typical pop fly,” Reid says. “You hear the crack of the bat and anticipate how far it was hit. Never gave it a second thought. It happens so often. I distinctly remember Edmead come roaring in and Cruz backpedaling with his head straight up. I believe they were both yelling for it.

“All of a sudden you see this awkward collision. It didn’t even look that bad. It looked almost like a flop. Cruz rolled over. He had his back to Edmead, who was flat behind him. Cruz was grabbing his knee, kind of screaming.”

Edmead’s head had crashed into Cruz’s right knee. “I was waiting for the ball,” Cruz says, “with all of my weight on my right knee because my left knee was up to catch the ball. And that’s when I felt the crash. I thought I got the worst part of it. I never thought it would end up the way that it did.”

Says Nicosia, “There is no completely getting over it. I can still hear that noise, that clash of that knee against his skull. I’ll never forget that sound. It was one of those things when you heard it, you knew it was a problem, like the sound of two cars colliding off in the distance. You shudder at the sound.

“I still wake up in the middle of the night and think about it. We were just young kids. It was unbelievable. I see it to this day: Pablo going back with his knee brace on, Alfredo coming in and sliding and . . . boom! You could hear that. When his knee hit his skull you could hear it. That noise . . . ugh, it was earth-shattering.”

Salem pitcher Jerry Thomas told his hometown paper, the Scranton (Pa.) Times-Tribune the next day, “I was one of the first guys out of the dugout to get to both Alfredo and Pablo. I knew Pablo was hurt bad because he was holding his knee, rolling in pain, but then I looked over at Alfredo and saw his face. . . . God, it was unbelievable.”

“The ambulance came into the outfield,” Cook says. “They said to me, ‘Bring some water and towels.’ The next thing you know I’m wiping up the blood with a towel where he fell.”

“They rolled Edmead over,” Reid says. “Everyone started bawling.”

“When I looked at him on the ground,” Thomas said, “I turned away and cried. I knew he was dead.”

Nicosia, the catcher, saw blood underneath Edmead’s head. “I was just 18 years old,” he says. “We looked around, and the other team had a trainer. We didn’t have one. That was typical back then. When he rolled Edmead over, I saw blue-and-yellow matter coming out of his nose. I had no idea what had transpired. I said, ‘What is that?’ The Candy Man [Candelaria] said, ‘That’s his brains.’

“Oh, my God. For young kids to process that . . .”

“There were people crying—players,” Nicosia says. “Johnny Lipon made everyone go away from the scene.”

“We stood and watched in silence like everybody else,” Reid says. “Everybody was just dumbfounded. Very swiftly they took him away. He looked dead. Motionless.”

Edmead and Cruz were rushed to Lewis-Gale Hospital. Kinder, the GM, followed them. Before leaving he told Langford, a pitcher on the squad, to wait in the press box for a call from him with an update. The game resumed.

An hour later, about 15 minutes before the last out, the call came. Edmead was dead. Kinder met Cruz at the hospital. Cruz refused medical attention. Still in uniform, he went home and buried his head in his hands.

“My God,” he said aloud. “My brother. My little brother. He always tried so hard. I didn’t see him.”

Kinder described Cruz that night as “absolutely distraught. . . . All Pablo has been able to say for three hours is, ‘Why in the hell didn’t it happen to me?’ Pablo was Edmead’s protector, guide and friend.”

The Pirates lost the game 10–9. Lipon gathered his team in the locker room to give them the awful news. “We just had a shack, basically, with a concrete floor,” Nicosia recalls. “Maybe 20 [feet] by 20. He told us he passed away on the way to the hospital. His head got hit and he was basically dead right there. That was tough for all of us to take. Johnny Lipon was crying.”

Lipon told reporters that night, “Alfredo enjoyed the game. God, he loved to play. You had to like him. He was so full of life. He was always smiling.”

Word quickly reached Amada and Alfredo Sr. in San Pedro de Macoris about the loss of their son, whom Amada called “the family’s great hope.”

“I feel as if my heart was destroyed,” she said.

The Aug. 30 Newport News (Va.) Daily Press reported, “The accidental death last Thursday of Alfredo Edmead, outfield star for Salem of the Carolina League, leaves one more sad footnote. . . . A Salem girl was engaged to the prodigy from the Dominican Republic, and all that was left to her was to linger longer after the many other mourners passed by in the final viewing.”

Thomas told the Times-Tribune the day after the collision, “The whole team is in shock today. Alfredo was the baby of the team. Everybody liked him. He invited me over to his apartment for a steak dinner next Monday. That’s the kind of guy he was—always going out of his way to be nice to people.

“Pablo’s blaming himself for what happened.”

Life and baseball dreams are only beginning in Class A. How do you go on after you have seen an 18-year-old die on the field?

“The initial impact was very shocking,” Prazych says. “That night I actually called my parents, just to talk to them about it. I know the next day we took the day off. I can vividly remember when we played again the day after that my mind wasn’t in the game. I had a ground ball go through my legs. It took a while.”

“The whole rest of my career,” Nicosia says, “and actually even to this day, any time I see a Texas Leaguer go up, I can’t watch what transpires afterward.”

Diloné fell into a slump that cost him the batting title. When he reported to spring training the next year, he switched his uniform from No. 1 to Edmead’s No. 7. But his heart wasn’t in it. “I didn’t want to play,” he said later. “When I got to spring training and he wasn’t there, I didn’t want to do anything. How could I without my best friend? I tried to forget it, but I couldn’t.”

He hit .217 in Triple A. “I couldn’t do anything right,” he said. “I thought about Alfredo all the time.”

It wasn’t until after the season that Diloné realized he could not change what happened and, as a pro, he would have to move on. He played 12 years in the majors.

Cruz initially was ruled out for the rest of the season because of the injury to his right knee. He was back in the lineup for the team’s next game. Why so soon?

“Because we were going for the championship,” Cruz says. “If we didn’t win those games we were going to lose the championship. I was playing hurt two days later.”

Six days after Edmead died, Salem, the first-half winners, beat Lynchburg 6–0 to clinch the second half and thus the Carolina League title.

A story began to circulate, even making its way into print, that Edmead died because the metal brace on Cruz’s left knee opened a gash in his skull. That is not so, Cruz says: “The impact was on the right knee. The brace was on the left knee. I almost had the ball in my glove when it happened.”

Haak would later say that the autopsy determined that Edmead had an abnormally thin and fragile cranium. Cruz’s knee, a fall on a sidewalk, a pitch to the head even with a helmet on—any sort of blow to the skull would have imperiled Edmead.

Then the 14-year-old ball boy, Cook is now president of BrightView Sports Turf Division, the official field consultant for Major League Baseball. A few years ago he was checking on fields in the Dominican Summer League when one of Edmead’s family members invited him to their house.

“They said to me, ‘You were there,’ ” Cook says. “They wanted to know about it. It was just me and the family. I sat there on the couch. My Spanish is a little limited. I can get by with some and I’d say about half of them did speak some English. It was a really moving experience.”

Across from Cook on a wall in the family living room hung a framed Salem Pirates jersey that belonged to Alfredo Edmead. “It was the jersey that he died in that night,” Cook says.

For many years, Cruz wore a physical reminder of that dreadful evening at the corner of Sixth and Florida: a grouping of thin, small lines of scars on the top of his right knee. They were marks from Alfredo’s teeth.

“Do you still have the scars?” Ismael, his son, asks him.

“No,” Pablo says. “They went away.”

It has been 47 years since Alfredo collided with Pablo. This is one of the rare times Cruz speaks in detail about it. The next day, he calls back. There is something else he needs to say.

“I’ve been blessed by God,” Cruz says. “I have so much to be thankful for. The people of the United States have been so sweet to me, especially in North Carolina and Virginia.

“There were so many great people with the Pirates who were so good to me. I spent 37 years there. And my wife, Josephina, was always at my right hand helping me sign so many great players. I have had my Little League for 56 years. We’ve helped people go to school and we’ve helped the church.”

On the night Edmead died, Kinder said, “He was such a spark of life. We all lost a little bit of our lives with him.”

And yet to be fully human means to carry on through the eternal push and pull of love and loss. Broken hearts still beat. We dance with a limp. Gratitude prevails.

• 'This Should Be the Biggest Scandal In Sports'

• FaZe Clan Is Changing the Game

• A Journalist Died Over a Soccer Feud. ... Or Was There a More Sinister State Plot Involved?

• Phillip Adams Took Six Lives, and Then His Own. How Many More Were Ruined?