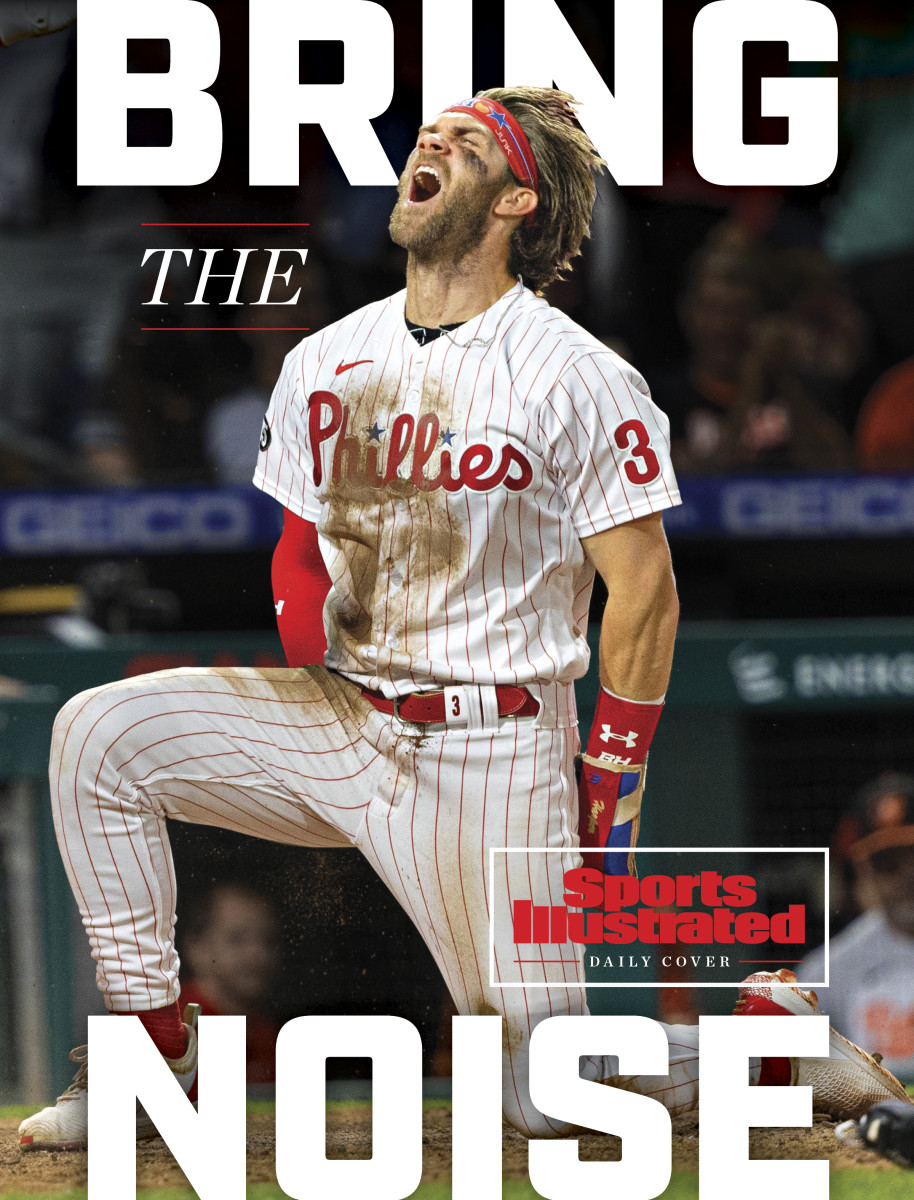

Bryce Harper Doesn’t Want Your Praise. But He Needs Your Doubt.

A friend from home in Las Vegas texted Bryce Harper out of concern. The friend noticed that Harper had turned off the comments to his Instagram account. His buddy tapped out a recent text wondering what was going on, worried the usual trolls and haters who infect social media had caused Harper to surrender as his Phillies try to end the longest current playoff drought in the National League.

Harper gave a quick smile when he saw the text. Then he tapped out this reply:

It was actually so I don’t have to listen to people talking about me winning an MVP. I like stuff that gets me going more. Makes me work and makes me the best version of myself.

Harper is a unique talent. He is the best fastball slugger in baseball, a smart hitter who doesn’t want his mind clouded with analytics, the major league leader in slugging and on-base plus slugging, the first left-handed hitter ever with 200 homers, 100 stolen bases and 800 walks at age 28, the first player to sign a contract worth $330 million and quite possibly the first person to shut down his IG comments for being too positive.

“Every time people start talking about numbers, I don’t even want to talk about it,” Harper says. “The media and everybody who brings up anything like that, no. I just want to win. That’s all I want to do.

“It’s not going to be perfect. It’s not going to be the best every single night. But all I want to do is give it my best every single night and be the best player that I can be and get us to where we want to be. And that’s October and playing super meaningful games.”

Harper would rather you doubt him (or worse) than praise him.

“I’ve heard the noise for so long it’s just another thing,” he says. “I hear it all the time. I hear it from everyone.”

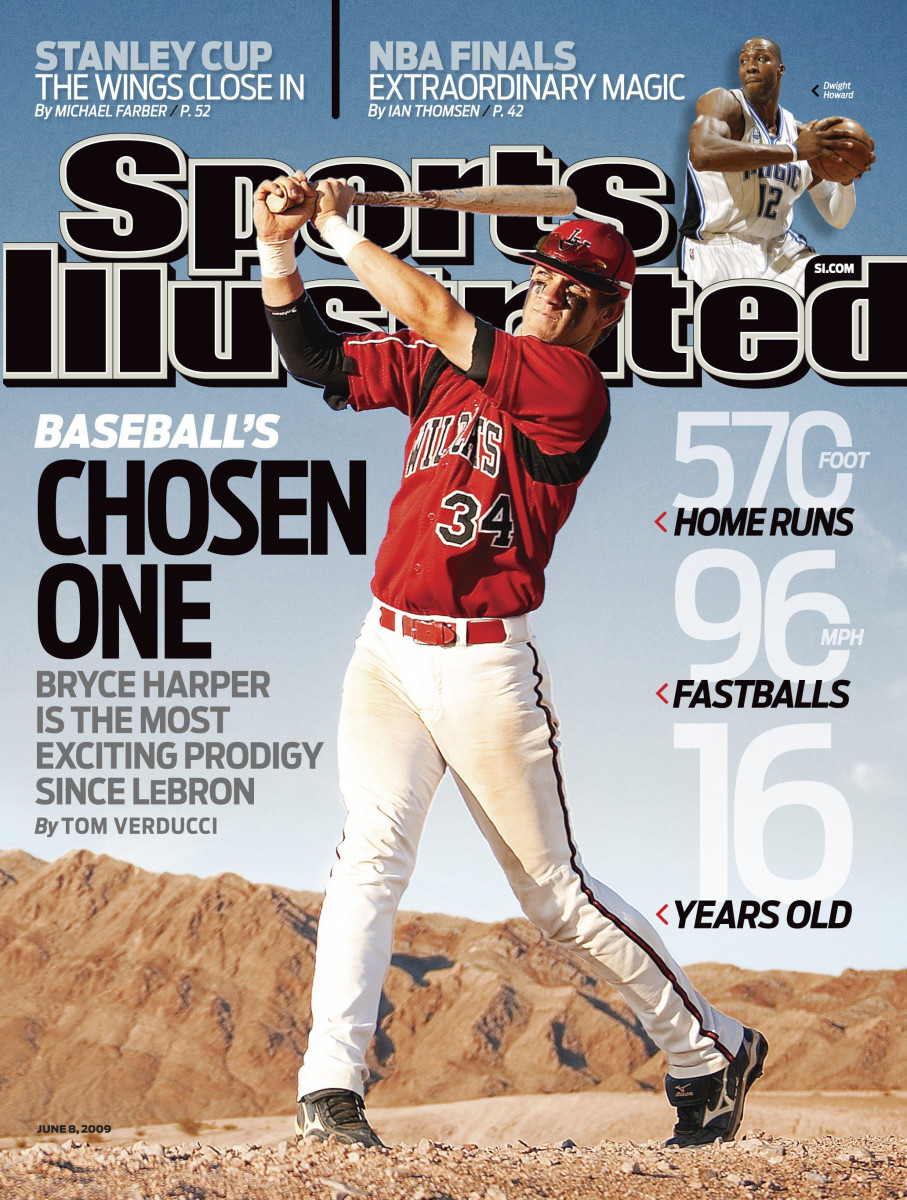

Ever since he was on the Sports Illustrated cover at 16—and probably even before that as a travel baseball legend—Harper has never played baseball in a neutral environment.

“And I don’t want that,” he says. “I want to be able to hear it, to feel that energy. I enjoy that. I enjoy going into a hostile environment, whether it’s New York, L.A. or now D.C. It’s just how it’s always been. I’ve learned to play with that and grow with that.”

Instagram comments aside, the drumbeat of Harper-for-MVP is growing in volume. He has pushed, pulled and willed a seriously flawed Phillies team that ranks 24th in bullpen ERA and last in defensive runs saved into last-week playoff contention. After losing to the first-place Braves on Tuesday night, the Phillies fell to three and a half games out of first place with five to play. They have two more games in Atlanta, followed by three at Miami. Harper has made possible Philadelphia’s long-shot chance to return to the postseason.

This season Harper has been hit in the face with a 97-mph fastball; played through wrist and shoulder injuries; stolen second, third and home in the same game; volunteered to catch (manager Joe Girardi declined the offer); and somehow put up the greatest second-half numbers in 15 years despite taking the most pitches out of the strike zone. Every opponent begins a series against Philadelphia with the mission of not letting Harper beat them, and yet still he does.

There is a predatory calm about the way Harper is playing baseball, a leonine patience to knowing when to attack. In his 10th season, Harper no longer runs into outfield walls, scuffles with teammates in the dugout or swings with back-twisting violence the way he did in his early years after reaching the big leagues at age 19. Married and the father of two children, Harper has found such an evolved equilibrium in his game and in his life that, once castigated as overrated, he has become one of the more underrated players in the game.

“Let’s keep it that way,” he says. “I’m O.K. with that. I am.

“For me, the more you look at what you’ve done in the past the more it doesn’t matter. What matters is the next [five] games. Because these games are important not just to me and my team but the owner, the staff and the fans of Philadelphia. If I was hitting .190 right now it still comes down to these games. Beyond all the awards—the MVP, that’s great, that would be awesome and amazing—but there’s nothing greater than having 26 guys come together and win a championship. I’m hoping one day I can feel that.”

According to his agent, Scott Boras, Harper gave up as much as $100 million in possible career earnings for the stability he has in Philadelphia. Winning the first playoff series of his career has remained more elusive.

Every time Harper takes the field at the start of a game at Citizens Bank Park, he sprints to his position in right field on an arc, like a fighter jet swooping in for a landing. He stops, and facing the fans in right field, he removes his cap and bows to them, then snaps himself upright with a dramatic flip of his thick bundle of hair and pulls the cap back on. It has become a popular bit of stagecraft. Not since Willie Mays kept running out from under a cap he deliberately chose one size too small has a player made the uncovered head such a signature look. In full sprint Harper often will throw his head back to dislodge his helmet, as if shedding unnecessary drag.

The capless outfield bow is more than a show of hirsute splendor. It is a statement of his happiness to be in Philadelphia through 2031.

“I enjoy playing here,” Harper says. “It makes me happy when I think about it. The fans are tough, but I absolutely love it. I try to give them my all every night. They know that. They hold you accountable for what you do, the way you act, and I love that. It’s fun, man, to play the game in front of fans who really give a crap about what’s going on.

“They give you the love every night. I run out to right field every night and I absolutely love it.”

Harper reached free agency at age 26 after a 2018 season with Washington that was considered a “down” year even though he led the league in walks (130), hit 34 home runs and drove in 100 runs. The Nationals had another teenage outfield star in the making, Juan Soto, and made little effort to keep Harper. The Dodgers spoke to Boras about signing Harper to a short-term deal with a high average annual value and opt-outs. They wanted to buy Harper’s prime years and allow him to hit free agency again at 29 or 30. Boras knew such a plan would maximize Harper’s earnings. Harper wanted no part of it. He instructed Boras to get the longest deal possible, with no opt-outs.

“Bryce came to me and said, ‘I want to be in one place for a long time,’ ” Boras says. “I’m saying, ‘You know, you’re a 26-year-old free agent.’ I took copious notes. He was adamant. I told him, ‘You may lose 50 to 100 million dollars.’ He said, ‘It’s worth it to me.’ ”

The Nationals won the World Series the next year. The Dodgers won it the year after that. Had Harper taken a three-year deal with Los Angeles, he might be hitting free agency again at age 29 with MVP numbers and a World Series ring.

“The Dodgers are an incredible team and organization,” Harper says. “They do a phenomenal job of bringing guys in to win year after year. But for me to do a short-term deal with opt-outs, knowing all you [reporters] would be talking about is, ‘Where is he going next?’—I didn’t want that. I did not want that for my family. I did not want that for myself. I did not want that for my sanity.

“In Washington, that’s all anybody talked about from day one. ‘Oh, he’s going here.’ ‘He’s going there.’ So I’m very happy with where I am. I think the team is going to have that success. We have the opportunity this year.

“I’m not going anywhere, and I love that feeling. I’m a Philadelphia Phillie and I love that. I love being able to say that. And I can say that for a long time. I’m able to go home each night. I don’t want to rent an apartment. All the little things that come along outside of baseball … spring training, shipping cars, driving my wife insane because she doesn’t know where we’re going to be. … My kids are going to grow up in Philadelphia. In this ballpark. I love coming to this ballpark. It makes me happy just thinking about.”

Harper’s wife, Kayla, his son, Krew, 2, and daughter, Brooklyn, 10 months, attend every home game. After games Harper drives 15 minutes to the family’s home in New Jersey.

“I get home, and the little man runs over to me and wants to play,” Harper says. “It takes your mind off the game and puts things in perspective. Then it’s bath time, we have dinner and hang out a bit. They go to bed around 1 a.m. and get up around noon. Brooklyn wakes up to feed. She’s a bottle feeder. She’s right next to us, so I hear her. She wakes up. Krew is in his room. I’ll take the feeding. I love it. When I’m home I love the peace and quiet of it—the feeling of being a family.

“Early in my career—and everybody does this, especially at 21, 22—when you first come up you’re always thinking about the game and what could I have done better. For me now, I don’t have time to do it. I might tell Kayla, ‘Man, that one pitch I should have hit 500 feet.’ She just laughs. She actually says, ‘Yeah, you should have.’ She gets it.

“When I’m home it’s family time. There are bigger things than baseball. But of course, for those four hours on the field, it’s the biggest thing in your life.”

Harper pulls out his phone.

“I’ve got to show you some pictures,” he says.

There is Harper snuggling with Brooklyn on a sofa. There is a video of Krew swinging a plastic bat in full Phillies uniform with his name and dad’s No. 3 on the back. Krew unleashes a wicked right-handed swing at a plastic ball thrown to him. He is a dead-pull power hitter.

“At 2, the best swing I’ve ever seen,” Boras says with a laugh. “You know, when you meet a child at 14, 15 years old, you have a responsibility to them. You’re a fiduciary. In the game you want them to be the player they should be. But what I’m really most proud of with Bryce is who he should be in the community, who he should be as a husband and who he should be as a father.

“Now he’s also understanding the dynamics of what it takes to be the greatest player he can be. There’s no question that he’s better than he’s ever been. The truth of the matter is he’s a more feared player and a more complete player.”

One day in the Phillies dugout, after Harper had pounced on a rare fastball thrown over the heart of the plate to him for a home run,J.T. Realmuto gave him a catcher’s perspective of how Harper has become more dangerous.

“When I was with the Marlins,” Realmuto told him, “there were times when we’d throw you three straight heaters over the plate and you’d take them and punch out.”

Says Harper, “He looked at me and laughed and goes, ‘Now you don’t do that anymore.’ I go, ‘I know. Now I’m ready to hit.’ Those are the things I had to learn over time. This is the big leagues, with really good pitching. You might get one or two pitches to hit an at bat or sometimes one or two pitches in a game. It’s about understanding who you are as a hitter and what you want to hit.”

Since the All-Star break and entering Tuesday, Soto and Harper rank first and second in pitches called balls. Pitchers threw Harper 56.5% of their pitches to him out of the strike zone in that time; only Salvador Perez and Shohei Ohtani saw a greater avoidance rate. Yet with so few pitches to hit, Harper is having the best second half of his career in all three slash categories (.342/.486/.725) and one of the best ever. Only six other players hit those second-half thresholds with at least 200 plate appearances: Ryan Howard, Barry Bonds (four times), Ted Williams (twice), Rogers Hornsby, Harry Heilmann and Babe Ruth (five times).

“We talked when he was younger about Barry Bonds and how Bonds used psychology and the perception of his power without taking a swing,” Boras says. “In his own way Bryce has applied that this year and he sees the impact and the force of it for the benefit of the team. He’s got people around him that can drive him in.

“For all of his power, people forget that his baseball instincts are off the charts. As a young player he ran into walls and between that and the force of his swing it was debilitating. Now he understands it’s not always needed. All those understandings are coming to the fore, and you’re starting to see the true greatness and consistency of his career.”

Says Girardi, “The most impressive thing about Bryce is his patience. He sees so few pitches to hit, and yet he will not expand his strike zone. Throughout this second half he has not altered one bit. He has kept the same approach. Kept the same plate discipline. It’s been impressive to watch night in and night out.”

As a young hitter, Harper would sit on breaking and off-speed pitches every pitch—an unheard-of approach because it’s almost impossible to react in time to velocity when you are sitting on softer pitches. He no longer sits on softer pitches. Asked to describe his approach now, he says, “I don’t really have a specific one.”

Just before game time he will watch how the opposing pitcher has pitched to Freddie Freeman, Joey Votto and Brandon Crawford, fellow left-handed hitters. He wants simple information about what pitches the pitcher throws. But that’s the extent of information he wants.

“Tendencies? No, I don’t want that,” he says. “It’s funny. [Former teammate] Jay Bruce would say, ‘I can look at that [tendencies] sheet a million times, but when you step in the batter’s box that’s all out the window.’ I just love to get up there and have a good at bat. Really, that’s all I really want to do.”

At least four times in polls of major league players has Harper been voted as the most overrated player in the game, most recently in 2019 with 62% of the vote, as compiled by The Athletic. Yet over the past four seasons he has played in 95% of his teams’ games while ranking among the top eight players in walks (first), times on base (second), OBP (fourth), runs (fifth), home runs (sixth), OPS (seventh) and RBIs (eighth).

The greatness of Harper is found in the rare dynamic versatility of his offensive game. He hits for power, controls the strike zone and runs the bases at superior levels for his age. Overrated? Harper is one of only three players with 200 homers, 100 steals and 800 walks through his age-28 season.

“Really?” he says when told of such exclusive company.

He is asked to guess the only other two players who were so accomplished so young.

“Maybe Trout?”

He is told he is correct about Mike Trout. One more.

“I’d say Bonds, I guess.”

Wrong. Bonds did not have so many walks.

“Was it Rose?”

No, Pete Rose did not hit any of the three benchmarks.

“Willie Mays?”

No, Mays did not walk nearly as much. A clue, he is told: The other player is a switch-hitter.

“Mickey Mantle?”

Bingo. Trout, a right-handed hitter, Mantle, a switch-hitter, and Harper, a left-handed hitter. That’s it.

“Nowadays, especially being able to walk is big,” he says. “People don’t walk as much because it’s about launch angle and hitting home runs, which is totally fine. I like that, too. One of the guys I like to watch is Soto. He’s very good because he handles the zone so well. You see guys like that, you see greatness. My dad always says when you start hitting is when you’re taking your walks and seeing pitches.”

Harper slugs .714 against fastballs, the highest mark in the big leagues. Pitchers know this. They rarely throw him fastballs to hit, especially inside. In 136 games this year Harper has seen 151 fastballs on the inside third of the strike zone. He slugs .892 on those rare treats.

On April 28, Cardinals left-handed reliever Génesis Cabrera reached back to throw one of those rare inside fastballs to Harper. It left his hand at 97 mph, but it also left his hand too early. The two-seamer flew toward Harper’s head. Harper bent back to avoid it, but because it was a two-seamer the spin gave it tailing action. As Harper’s head tilted back, the pitch followed it as if guided by radar. The 97-mph fastball hit him in the face. It bounced off his face and hit his left wrist.

Harper’s helmet flew off. He took his right hand off the bat as he fell to the ground. As he rolled over into a fetal position, Harper drew his left hand to his face to do a bit of inventory.

“Probably not the smartest thing to do, right?” he says. “But I just wanted to see if anything was broken or I could feel anything. Once I felt that nothing was broken, I looked for blood. There was some on my nose. Once I got up I thought, I’m strong. I’m ready to go. But as I walked off the field I started to think, Man, am I going to be O.K.?

“You start thinking about your family. You start thinking about the what-ifs. You start thinking about one millimeter up or one millimeter over and you’re having a very different conversation.”

One of the first people Harper reached out to was Cardinals manager Mike Shildt.

“I wanted to make sure Cabrera was O.K. as well,” Harper says. “You hit somebody like that and it’s a terrible situation for the pitcher as well. You’re not trying to do it.”

Harper had to rebuild that confidence every hitter must possess just to step into the box—the willful ignorance of the consequences of one errant pitch that lies beneath the surface like some bottom-dwelling predator in the ocean. The only way to get in the water is not to even think about what is lurking in the depths of darkness. The minute you fear the predator you are done. He started with swings off a tee, then flips from a coach, then batting practice from a coach, then batting practice off a high-velocity pitching machine.

“I got to where I was O.K. in the box,” he says.

He missed only three games. Over his next 20 games Harper hit .200 with two home runs. The problem was not the psychological residue of getting hit in the face. It was the soreness in his left wrist.

“Once it started to feel better, I was good,” he says. “Now I don’t even think about it.”

Starting June 12, Harper reached base 178 times in 92 games while slugging .694. In the 22 games leading into the series against Atlanta this week, Harper posted a ridiculous slash line of .377/.532/.841 while reaching base 50 times, including at least once in every game. He has scored a run in 20 of Philadelphia’s past 22 wins. The Phillies are 54–24 when Harper scores and 27–52 when he doesn’t.

His 1.214 OPS in September is the best in baseball other than the 1.283 by Soto, who may be his top competitor for the MVP award, though Harper’s work is being done in a pennant race with little margin of error. Soto plays for a last-place team.

In 2009, when he was a high school sophomore, Harper told SI about his goals: “Be in the Hall of Fame, definitely. Play in the pinstripes. Be considered the greatest baseball player who ever lived. I can’t wait.”

He was a kid. His crime against baseball was that he dared not just to be great but also to speak it. He was the first pick at 17, a big leaguer at 19 and an MVP at 22, the youngest unanimous such award winner. Expectations soared even higher. He grew up in the public eye, one of the first true MLB stars to play entirely in the age of social media. He has known only the vortex of scrutiny, which draws more of its energy from dislike than like, from what we lack rather than what we are. For so many years what he did never seemed to be enough.

Ten seasons in, he has made it here to the last week of this season as a man in full. He is a better ballplayer than ever and a husband and father growing family roots in Philadelphia. In a season that began with a 97-mph fastball to the face, Harper is trying to pull the Phillies into October like those strongmen who pull heavy construction vehicles with their teeth. The odds are against him. The atmosphere hostile. The stakes high. The time short. Bryce Harper is in his element.

More MLB Coverage:

• Will the Cardinals' Hot Streak Matter in the Playoffs?

• How to Judge Trevor Bauer

• Joey Votto Is Finding Satisfaction in Abandoning Perfection

• Will This Mariners Rebuild Be Any Different?