How We Should Remember the Epic Dodgers-Giants NLDS

Last night’s thrilling season finale between the Dodgers and Giants was a captivating display of everything that’s great about baseball. It was a win-or-go-home playoff game between the two best teams in the majors, who are also MLB’s two oldest rivals. It was decided by a single run, after the NL West standings were decided by a single win.

It pinned the defending champs against the team few thought would contend, and it demonstrated two different ways to succeed today. San Francisco starter Logan Webb delivered one of the greatest postseason pitching performances in recent years (7 IP, 1 ER, 4 H, 1 BB, 7 K), less than a week after his even better outing in Game 1 (7 ⅔ IP, 0 R, 5 H, 0 BB, 10 K). Los Angeles went with two one-inning relievers to open the game, before bringing 20-game-winner, lefthanded starter Julio Urías, out of the bullpen to begin the third inning. The Dodgers then went with closer Kenley Jansen in the eighth inning and ace Max Scherzer, the favorite to win the NL Cy Young award this year, to pitch the ninth.

It showcased four former MVPs (Mookie Betts and Cody Bellinger for the Dodgers; Buster Posey and Kris Bryant for the Giants), who went a combined 8-for-16. It also featured Darin Ruf, a former big league castoff who spent three seasons playing in Korea, who hit a 452-foot home run to dead center field.

And yet, this game also presented two of the more pressing problems that baseball needs to address—one way or another—in the near future: replay review and the role of human umpires. Both of these are very much connected, but they are not the same issue, and therefore, they will require two different solutions.

Replay review is going to get far more attention in the coming days because its limitations directly ended the game. Wilmer Flores was behind in the count, 0–2, against Scherzer with two outs, a runner on first base and the Giants down a run. Scherzer threw a low-and-away slider and Flores started his swing. Home plate umpire Doug Eddings appealed to first base umpire Gabe Morales, who punched him out. Replays showed clearly that Flores didn’t swing, but check swings are not reviewable. There was no way for San Francisco to appeal Eddings’s appeal to Morales. Game over.

Let’s be frank here. If check swings were replay-reviewable, and the umpires looking at the play at MLB headquarters made the correct decision and overturned Morales (which is never guaranteed), it probably wouldn’t have mattered. Scherzer was almost certainly going to strike out Flores, or at least retire him, anyway. But, the exposure that such a controversial ending receives does allow us to consider the flaws of the league’s replay rules. Among some of the other nonreviewable plays: fair/foul calls that are at or in front of the first- and third-base umpires; infield fly calls; foul tips; possible trap plays that occur in the infield; ball-and-strike calls. Some of these are considered subjective calls—like check swings, infield flies and the strike zone.

But, replay was implemented to overturn the egregiously incorrect calls on the field in the most consequential moments. I get that there aren’t definitive answers for these judgment calls—could an infielder make this catch with reasonable effort, even if he’s in the outfield? Did the batter actually swing at that pitch? What is a swing, anyway?—but the replays for plenty of reviewable calls aren’t conclusive, either.

This brings us to the other of the two dilemmas: the role of human umpires. Typically, the case for replacing them applies only to implementing an automated strike zone. People will still make all the other umpiring decisions. But in the Atlantic League, where they’ve experimented with so-called "robo-umps," there have been problems because the computer’s calls aren’t always accurate.

Fans and baseball writers alike point to the strike-zone boxes superimposed on broadcasts or charted on game feeds as evidence that baseball needs automated strike zones, or just to vent their frustrations that a human made another mistake. But these graphic representations of the strike zone, along with the location of the pitches, aren’t completely accurate—and not all tracking systems register pitches the same way. Which automation would the league use?

So, what the heck is baseball to do? Here are some possible solutions:

- Make all calls reviewable, even if they are considered subjective.

- Don’t tell the umpires back in HQ what the call was on the field. Let them make the call as they see it based on all the slow-motion replays and various camera angles they’re watching. These replay umpires shouldn’t be tasked with deciding whether the various videos they’re examining contain enough evidence to overturn a call from one of their comrades. They should just use the additional tools at their disposal to make the call as they see it.

- Automatically review all walk-off hits or final outs. This is like what the NFL does for scoring plays or turnovers. Almost all of these calls will not be overturned, but this adds an extra safety net just in case.

- Let managers appeal balls and strikes. Give them two challenges that they can use during games, but don’t allow them to call a replay coach for input. If the ball-strike call is so bad that it warrants a review, the skipper should be able to see that from the dugout. Because managers won’t be on the phone waiting for another coach to watch the play before deciding to use a challenge, this shouldn’t hold up play unless the manager actually appeals a call and it is actually reviewed.

- With that in mind, just get rid of the whole call-to-coach-for-input thing altogether. This just causes unnecessary delays to the game, and it should help limit the reviews of whether a player’s foot or hand dislodged from the base for a microsecond while the tag was still on him. The fewer arguments over the “Spirit of the Rule!”—the better off baseball will be.

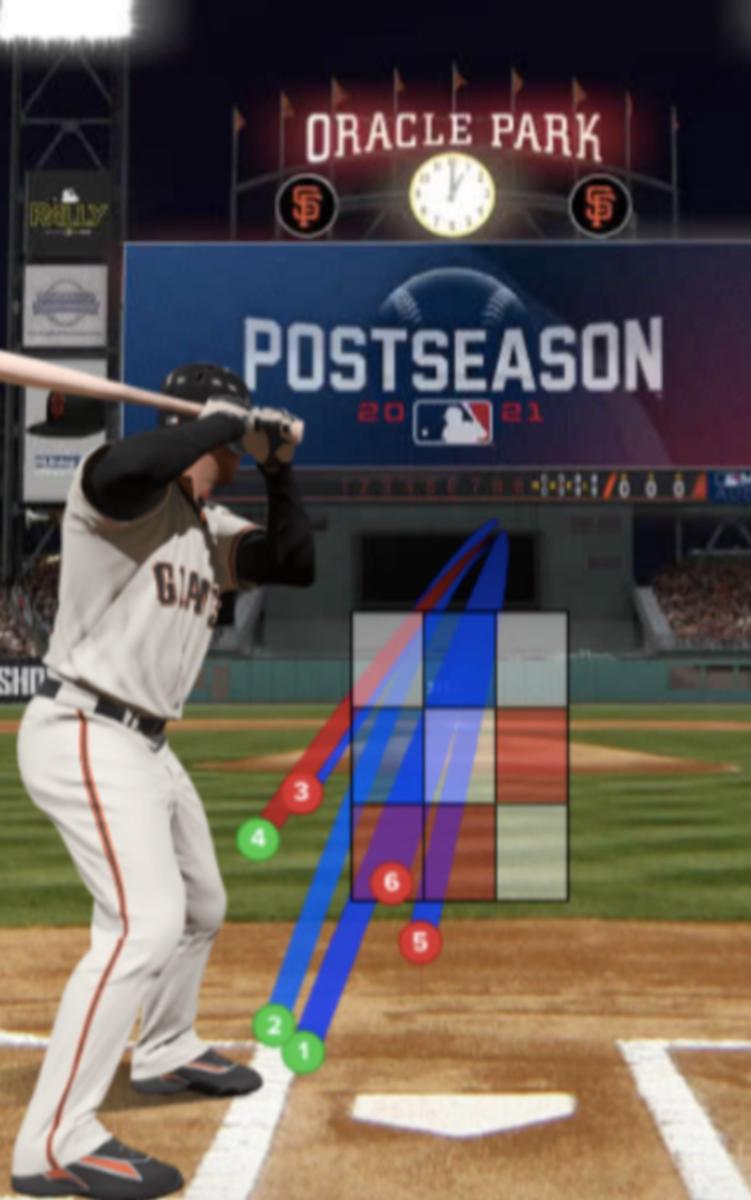

Proposal No. 4 would’ve prevented another set of woeful calls from last night that perhaps had an even greater impact on Game 5 than the check-swing debacle. But they didn’t draw as much ire because they came in the fourth inning. Brandon Crawford led off with a single to left field against Urías, who fell behind in the count 2–0, facing Bryant. Eddings then called the third pitch a strike, even though it was obviously low and inside. The next pitch was called a ball. The fifth pitch of the AB was called a strike as well, even though it too was clearly low. Bryant then swung through the sixth pitch for strike three. If managers could challenge called strikes or balls, Gabe Kapler probably would’ve asked for a review of the third pitch. The call would’ve been overturned, pushing the count to 3–0, and Bryant would have walked on the fourth pitch to set up first and second with nobody out.

In these situations, teams on average score 1.373 runs before the end of the inning (though the specific run expectancy varies depending on the run scoring environment), according to FanGraphs. Before Bryant’s strikeout, the Giants had a run expectancy of 0.84, according to the FanGraphs play log. That dropped to 0.50 after the K.

There were plenty of reasons San Francisco lost this series that had nothing to do with bad umpiring, the most obvious one being that its lineup didn’t score enough runs: The Dodgers outscored the Giants, 18–10, across the five games. (Granted, Los Angeles was shut out in both of the games it lost.) So let’s not let a few bad calls take away from the epic series.

Instead, this is how I’m going to remember this game, this series and this season of Dodgers-Giants. When it was all over, the scoreboard read: Dodgers 2, Giants 1. That score might as well have been Dodgers 110 wins, Giants 109 wins. It was that close, that enthralling, all the way to the finish.

1. THE OPENER

“Three hours and 19 minutes into the best game in recent memory ... the visiting bullpen door at Oracle Park slammed open.” It was Max Scherzer, who rocketed toward the mound to pitch the final inning of the NLDS.

This is the way Stephanie Apstein sets the scene in her excellent column from last night’s game. She goes deep into the Mad Max Experience of the decisive Game 5 and breaks down how the Dodgers finally closed out the Giants.

Read Stephanie’s entire story here.

2. ICYMI

Miss some or all of NLDS Game 5? Experience all the action as it unfolded with our live blog.

Dodgers Outlast Giants in Game 5: Live Blog by Emma Baccellieri and Matt Martell

Relive in real time the epic conclusion of the NLDS between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Need a primer on where things stand in the American League before Game 1 of the ALCS tonight? We’ve got you covered:

Eight Things That Will Decide the Astros–Red Sox ALCS by Tom Verducci

This matchup features two of the best offenses in baseball, but hitting alone won't settle the series.

ALCS Predictions: Who's Going to Win? by SI staff

Will it be the Astros or Red Sox representing the American League in the World Series? Let's make our picks.

3. WORTH NOTING from Stephanie Apstein

Wednesday night, Giants manager Gabe Kapler got an unexpected text from his Dodgers counterpart, Dave Roberts: Righthanded reliever Corey Knebel would start Game 5 of the National League Division Series. Lefty Julio Urías had been scheduled to take the ball, but Los Angeles had decided to mess with San Francisco’s lineup by using an opener. That was the story before the game. Was it the kind of creative thinking that has separated the Dodgers from most of their peers? Or was it another example of a computer making a decision that ignored the human element?

The latter, apparently. Knebel and righty Brusdar Graterol, who followed him, allowed traffic on the bases but no runs. The Giants had to burn pinch hitters to replace lefty hitters Tommy La Stella and Mike Yastrzemski after one plate appearance each. And Urías allowed just one run in four innings. “Our openers worked,” said ace Max Scherzer, who got the save. “Everybody kind of doubted that at first, but it worked.”

4. WHAT TO WATCH FOR from Will Laws

Houston will host the Red Sox tonight to kick off the American League Championship Series at 8:07 p.m. ET. It’s a rematch of the 2017 ALDS (which the Astros won in four games en route to a championship) and the 2018 ALCS (which the Red Sox won in five games en route to a championship). But a lot of the faces from those series have changed.

Houston’s entire rotation will look different. Even Lance McCullers Jr., who came out of the bullpen back then, is expected to miss the series after leaving Game 4 of the ALDS with forearm tightness. In his absence, Framber Valdez will assume the role of Astros ace and start Game 1 after drawing the same assignment last year. Valdez was lit up by the White Sox in Game 2 of the ALDS, but the 27-year-old lefty was quietly Houston’s best starter during its surprise run to the 2020 ALCS, posting a 1.88 ERA over 24 innings. He also held the Red Sox to two runs over 14 ⅓ innings in back-to-back starts against them in June.

Opposing Valdez will be Chris Sale, who’s completed six innings just once in 10 starts this season since returning from Tommy John surgery and gave up five runs in just one inning of work against the Rays in his last outing. It won’t get any easier against the Astros, who just obliterated a White Sox pitching staff, which had MLB's highest strikeout rate and the AL's second-best ERA, and led the majors this season with a 117 wRC+ against lefthanders.

5. THE CLOSER from Emma Baccellieri

For many pitchers, I’d imagine that closing out Game 5 of the NLDS would probably make you ineligible to start Game 1 of the NLCS. For Max Scherzer … well, the man is simply built differently.

Skipper Dave Roberts said late last night that it was likely he would be good to go for Saturday. It helps, of course, that Scherzer needed only 13 pitches to get through the ninth inning to record his first career save in Game 5. It also helps that he’s Mad Max. The Dodgers have enough pitching depth that they don’t need to go this route. But if Scherzer feels anywhere near good enough to try it, assume that they will.

That’s all from us today. We’ll be back in your inbox tomorrow. In the meantime, share this newsletter with your friends and family, and tell them to sign up at SI.com/newsletters. If you have any questions for our team, send a note to mlb@si.com.