Why Does MLB Still Allow Synchronized, Team-Sanctioned Racism in Atlanta?

Seven months ago, Major League Baseball moved the All-Star Game out of Atlanta in response to institutional racism. On Friday, it will hold the World Series there—and this time, MLB is the institution supporting racism.

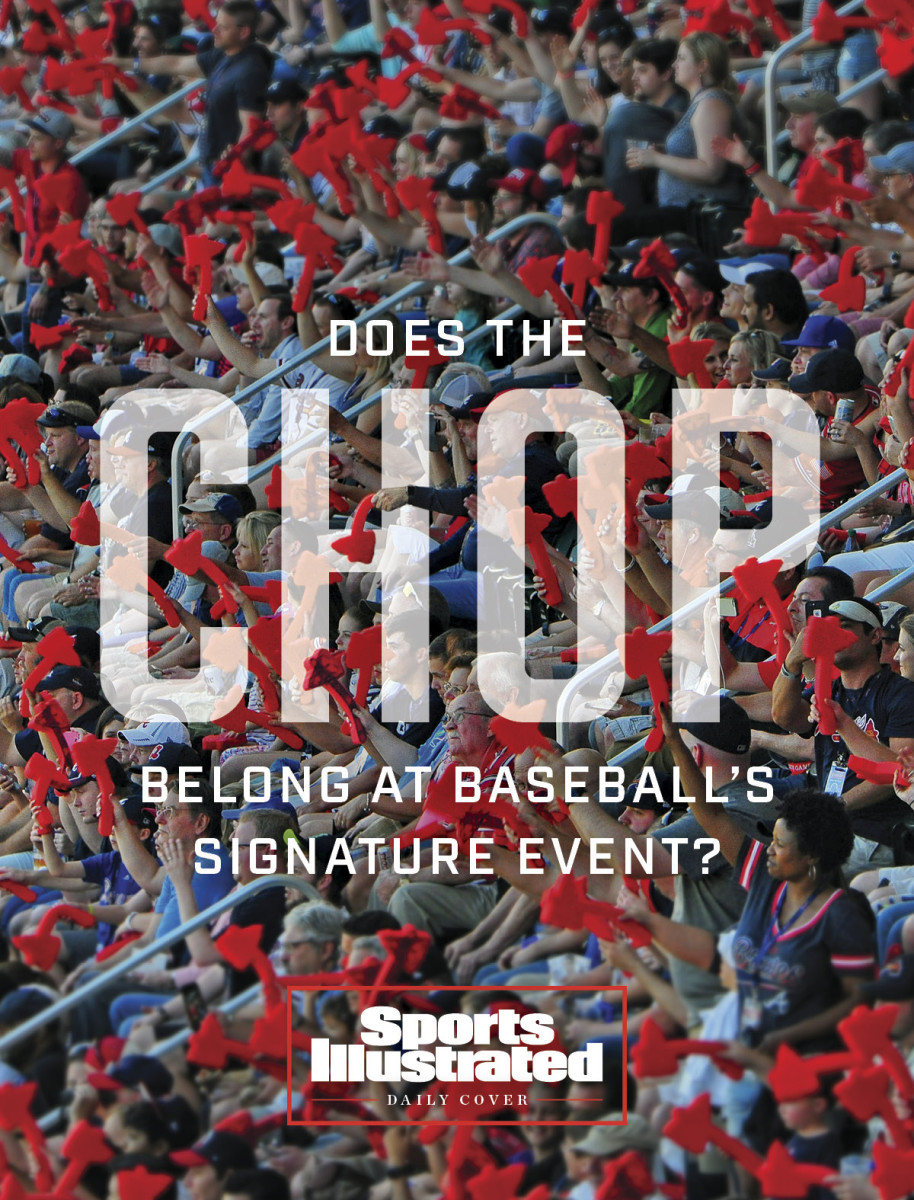

The name “Braves” is bad enough. Fans might see it as honoring Native Americans, but in equating them to Tigers and Cardinals, it dehumanizes them. Beyond the name, though, the crowd’s favorite gesture, known as the tomahawk chop, is unconscionable. At every home game, fans raise and lower their right arms in unison, howling a mock war chant. “It’s offensive,” says Claudio Saunt, a professor at Georgia who specializes in Native American history. “I also find it kind of embarrassing, just knowing that the whole country is seeing it on national TV.”

Anyone tuning into World Series Games 3, 4 and 5 will be subjected to this synchronized racism dozens of times: any time the home team scores, any time the opposing team changes pitchers, any time it has been too long since a largely white crowd mocks a people its ancestors tried to erase.

Is this what MLB wants at its signature event?

Evidently. The tomahawk chop is sanctioned by the team, and therefore by MLB. In 2017, commissioner Rob Manfred began to pressure Cleveland to “transition away” from its Chief Wahoo caricature; eventually Cleveland dropped both the mascot and the Indians name. In April, Manfred relocated the All-Star Game to Denver after Georgia passed a law that made it more difficult for people—especially Black people—to vote. Yet Atlanta can lead its fans in a racist chant throughout the game, and MLB does nothing—and therefore supports it.

“The Native American community in that region is fully supportive of the Braves’ program, including the chop,” Manfred said before Game 1 of the World Series. “For me, that’s kind of the end of the story.”

As to the concerns of Native Americans outside that region, he said, “We don't market our game on a nationwide basis. Ours is an everyday game. You have to sell tickets every single day to fans in that market. And there are all sorts of differences among the clubs, among the regions, as to how the game is marketed.”

The team declined to address the chop specifically but offered a statement that reads, in part, “The Atlanta Braves proudly elevates [sic] Native American culture and language on a continuous basis. Our efforts are ever evolving, and always in partnership with the Native American community. We firmly believe that the strength, courage, and resiliency of all Tribal Nations should be honored and esteemed by Americans every day.”

As an example of those efforts, the team pointed to a working group it has established to promote awareness of Native American culture, to a Cherokee exhibit at Truist Park and to a T-shirt emblazoned with the word “ballplayer” in Cherokee syllabary, proceeds from which it donated to the Cherokee Indians Speakers Council and to the New Kituwah Academy. The team also has a corporate partnership with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who own Harrah’s Cherokee Casino Resort. EBCI chief Richard Sneed shouted, “Play ball!” before Game 1 of the NLCS.

Sneed, who says he does not believe that his financial relationship with the team presents a conflict of interest, says he does not personally find the chop to be disrespectful. “There are huge issues that are facing Indian country, and I get a little bit frustrated when it seems to be the only thing that people are outraged about is somebody swinging their arm at a baseball game,” he says, citing the disproportionate rates of poverty, sexual assault and substance use that Native Americans face. “I’ve been asked previously, ‘Are you offended by the tomahawk on the uniform?’ Like, why? A tomahawk is an inanimate object. Why would I be offended by that?”

Most Native American groups disagree. In large, they say that, given those serious issues, it is especially cruel to have thousands of people making fun of Native Americans at a baseball game. “It is overtly racist,” says Aaron Payment, secretary of the National Congress of American Indians and chairperson of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. “Whether people understand it or not, it’s overtly racist.”

NCAI president Fawn Sharp released a statement on Wednesday criticizing Manfred's comments. It read, in part, "The name ‘Braves,’ the tomahawk adorning the team’s uniform, and the ‘tomahawk chop’ that the team exhorts its fans to perform at home games are meant to depict and caricature not just one tribal community but all Native people, and that is certainly how baseball fans and Native people everywhere interpret them. ... In our discussions with the Atlanta Braves, we have repeatedly and unequivocally made our position clear – Native people are not mascots, and degrading rituals like the ‘tomahawk chop’ that dehumanize and harm us have no place in American society."

Game 1 of the NLCS featured 14 chops; Game 2, 20; Game 6, 24, including three on consecutive pitches. Roughly half of these were instigated by fans; the rest were team-initiated, complete with music piped over the PA system and graphics splashed across the jumbotron. During each pitching change, the team went so far as to darken the stadium to set the mood, as fans used their cellphones while they chopped to create a racist light show. And the spectacle travels: During Game 4, which Atlanta won 9–2, a few chops broke out at Dodger Stadium.

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every day during the World Series.

If this seems like an old complaint, it is—and that is an indictment of the team. Thirty years ago this week, before Game 1 of the 1991 World Series between Atlanta and the Twins, some 800 people protested the chop outside the Metrodome in Minneapolis. Although nothing much changed, they did get the attention of at least one prominent fan—actor Jane Fonda, then engaged to Ted Turner, who owned the team. “I’m sorry it offends them and I’m not going to do it anymore,” she said.

It would be nice to see anyone with the Atlanta organization or MLB publicly display that kind of open-mindedness these days.

“We have reached out to [Atlanta], but we haven't had any real interest on their behalf,” says Payment, who advocates on behalf of the NCAI for sports teams to ditch Native American mascots and imagery. “We haven't really had a lot of luck there.”

During the 2019 NLDS against the Cardinals, St. Louis pitcher Ryan Helsley, a member of the Cherokee Nation, expressed frustration with the tradition. “I think it’s a misrepresentation of the Cherokee people or Native Americans in general,” Helsley told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, adding that it depicts them as “caveman-type people” who “aren’t intellectual.” He called it “disrespectful.”

Atlanta’s response was to stop handing out foam tomahawks to fans. It also said it would cease playing the music and graphics—only when Helsley was in the game. (He did not appear again in that series.) Fans chopped on.

Atlanta lost that series, and team CEO Derek Schiller, who declined to be interviewed for this story, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution before the next season began, “It’s a topic that deserves a lot of debate and a lot of discussion and a lot of thoughtfulness, and that’s exactly what we are doing.”

That debate and discussion and thoughtfulness led them here, to a stadium full of people whooping.

Why is this still happening? There are plenty of other ways to celebrate a home run or intimidate opponents during a pitching change. Sports Illustrated could not find anyone who said that the chop was helpful to Native Americans. No one, either, would cop to enjoying racism, although there does seem to be an element of defiance. Mostly the chop’s defenders cite tradition.

The Boston Braves got their name in 1912, after Red Stockings, Red Caps, Beaneaters, Doves and Rustlers all failed to catch on. The new moniker was a reference to owner James Gaffney, who belonged to the Tammany Hall political organization, which was named after Lenape chief Tamanend.

“That was an era when white people thought that Indians were backwards, that they were incapable of surviving in the modern world, and that they were going to vanish from the face of the earth,” says Saunt. “Any claim that this is a way of honoring Native peoples—you need to put that in the perspective of the longer history.”

The team moved to Milwaukee, then to Atlanta. Along the way it acquired as a logo a caricature called the “screaming Indian” and a mascot named Chief Noc-A-Homa, a man dressed in Native American attire who danced and set off smoke bombs from his teepee in the left field seats. Chief Noc-A-Homa was retired in 1986 when the team argued with his portrayer, Odawa Tribe member Levi Walker, about payment. The logo made it to ’89, a “Scalp ’em” billboard to ’92.

The chop is widely believed to have followed outfielder Deion Sanders from Florida State when he joined Atlanta in 1991. “We don’t discourage any of that,” Stan Kasten, then Atlanta’s president, told the Los Angeles Times in ’92. The chop salute, he argued, ridiculously, "doesn’t have anything more to do with Indian culture than the wave.” Kasten now holds the same role with the Dodgers. Asked before Game 2 of the 2021 NLCS whether his feelings on the matter had evolved, he declined to comment.

Georgia, though, has a lot to do with Native American culture. It was largely due to the state’s influence that the Indian Removal Act of 1830 passed. That law led to the Trail of Tears, the forced migration of some 100,000 people from the southeast to territory in what is now Oklahoma. Some 15,000 people died along the way. The Indian Removal Act was one of the most contentious pieces of legislation to that point; it passed the House of Representatives by only four votes. All seven of Georgia’s members of Congress voted yea.

“Georgia played a really oversized role in formulating Indian policy and Indian removal,” says Saunt. “Without Georgia’s politicians pushing it on the national stage, [the Indian Removal Act] would not have unfolded in the way it did.”

Ninety percent of the people who responded to an AJC poll last year said the team should keep its name. Seventy-five percent said it should keep the chop. Perhaps those people did not ask the original residents of the area.

“I have maps—there were Cherokee families living right near Truist Park who were forced out of their homes by state militia in 1838,” Saunt says. “It’s very personal.”

The need for change is supported by research. A 2008 series of studies published in Basic and Applied Psychology found that “exposure to American Indian mascot images has a negative impact on American Indian high school and college students’ feelings of personal and community worth, and achievement-related possible selves.” This among a youth population that already suffers 2.5 times the national suicide rate.

In some places, Native people have reclaimed terms such as Braves and Warriors. Sneed points out that athletes at Cherokee High School, in North Carolina, compete as the Braves. But fans of those Braves do not do the tomahawk chop at games.

“It’s like if someone denigrated Christianity or 9/11 jumpers,” says Brett Chapman, a Native American rights attorney and enrolled member of the Pawnee Nation who is a vocal opponent of Native American mascots. He imagines 50,000 people in a stadium dressed as Jesus Christ or screaming gibberish in mockery of the national anthem. He imagines the reaction that would get.

Payment suggests another analogy. “If we had an African American team [name] and [fans] were doing a Black minstrel dance, that would be very obviously racist,” he says. “So then the question is, Well, why don't people understand that for American Indians? And it’s because we don’t learn very much about Indians. In the public education system, you learn one unit in third grade, one unit in seventh grade social studies and then you learn a little bit on Thanksgiving, and usually what you learn is horribly inaccurate. And so American Indians are objectified as relics of the past. And I think most people don’t realize that we’re still here. And so they don’t think too much about how offensive it is, because they don't really understand that we are still here and that we exist.”

This was always wrong. But now that the Washington Football Team and Cleveland have abandoned their racist names, the chop is aggressively, defiantly wrong.

Meanwhile, Atlanta officials continue to claim impotence. “No matter what the decision is from our vantage point,” Schiller told The AJC, “this started as a fan initiative, and the fans are likely going to keep doing it anyway.”

Officials from another championship-contending franchise have made similar claims. The NFL's Chiefs, who call their version of the racist gesture the Arrowhead chop, have also received complaints from Native American groups and have also rebuffed them by deferring to the fans. The league has not intervened; to the contrary, commissioner Roger Goodell did the chop during the 2020 NFL draft.

So Atlanta has a chance to set an example. It’s time for the team to show the courage it claims its name represents. It no longer distributes foam weapons en masse, but it has much more work to do. Officials should announce that they no longer tolerate that particular brand of bigotry. Nix the graphics and the music. Then start throwing people out of the stadium. MLB should step in here, too, with fines that could escalate to baseball penalties until Atlanta takes action. If the team starts losing draft picks, it would pretty quickly figure out a way to put a stop to this. Fans of Mexico’s national soccer team have long chanted an anti-LGBTQ slur; the national federation enforced policies this year to eject fans who yell it and to stop matches if it continues. In September, the team played a World Cup qualifier in an empty stadium as punishment.

The Atlanta organization, meanwhile, leans into racist imagery. It seems to know the chop is offensive—before the 2020 season it changed its slogan from “Chop On” to “For the A”—but tomahawk branding still pervades Truist Park, from the logo painted behind home plate to the Coors Light Below the Chop seating area in right field. There would surely be a financial cost to a rebrand, but the team certainly can afford it.

Native American activists say they would like to see the Braves’ sponsors—Truist, Delta, Nike, State Farm and Miller Coors—speak out, as FedEx did about the old Washington Redskins’ name. It was only after the company threatened to pull its funding that team owner Dan Snyder changed the name. So far, businesses associated with Atlanta do not seem ready to take that kind of action. In a statement, Truist says, “We support the Atlanta Braves and their work with the Native American community on the responsible use of Native American culture and imagery in the sport.” Delta, Nike, State Farm and Miller Coors did not return requests for comment.

Payment thinks, though, that a change is going to happen—eventually. “History will be on our side,” he says. “The grandchild of the owner of the team is going to look back at it and say, ‘Oh, my god, Grandpa was a racist. Why’d it take so long?’ I think that's what will happen. I think it's inevitable.”

In the meantime, the team chops on. During the 14th chop of the night in Game 1 of the NLCS, Atlanta switched its jumbotron image from its tomahawk graphic to a new one, designed to encourage the fans to be offensive more loudly: “I CAN’T HEAR YOU.”

Yes, we can.

More MLB Coverage:

• Dusty Baker's Time Is Now

• Braves' Big Blunder Puts Game 2 Out of Reach

• Jose Altuve Snaps His Slump With the Help of a Playoff Legend

• Morton's Mystique Grows With Gutty Game 1 Performance