This Is the Path MLB Chose

It’s fair to say that you saw this coming. Maybe you saw it when negotiations between players and owners flared and sputtered over the last week. Maybe you saw it earlier in the lockout: days, then a month, then more spent waiting for the league to make a proposal on core economics. Maybe you saw it before any of this officially started, in the years since the last collective bargaining agreement, as players shared their frustrations with the system. It’s fair to say that you knew this would not play out easily—that it was all but guaranteed that MLB’s outlook for a new CBA, and for its season as a whole, would still be up in the air when the calendar hit March.

But it’s not fair to say this was inevitable. Because it wasn’t.

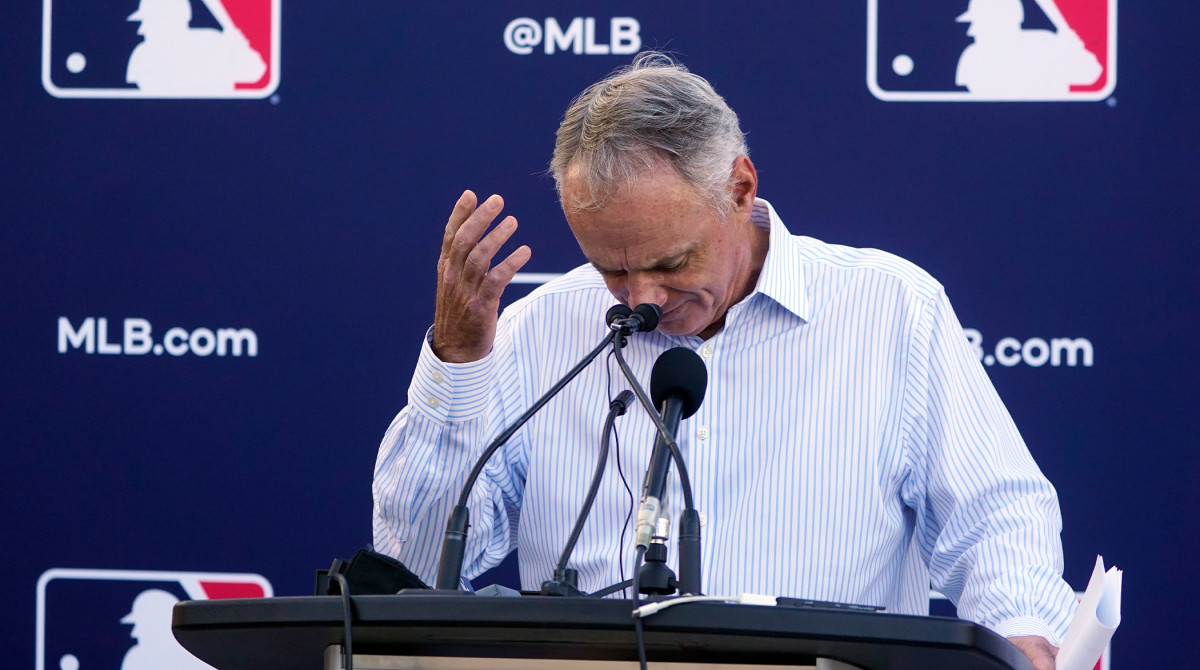

Commissioner Rob Manfred announced on Tuesday afternoon that the first two series of the year will be canceled. Opening Day is gone. “I had hoped against hope that I would not have to have this particular press conference in which I am going to cancel some regular-season games,” he said. This was his opening statement—language that he had time to prepare and rehearse. I had hoped against hope that I would not have to have this particular press conference.

Have to? Who says he had to?

It’s true that 5 p.m. on Tuesday came and went—the hour the league had called the final deadline to reach a deal or miss games. But MLB originally said the final deadline was Monday evening. Yet when that rolled around, there was still a deal to be made, so both parties stayed at the negotiating table to work one out, and the league revealed that a final deadline didn’t have to be so final after all. There was room to move here: 5 p.m. on Tuesday was a goal from the commissioner’s office, not an edict from on high, and there was room for flexibility. There was room to keep negotiating. There was room to take action other than calling a press conference and canceling games.

Yet this is the path MLB chose. The league made it sound as if it had no choice in the matter. But it’s made plenty of choices throughout this process—and it’s those same choices that have led it here.

The league chose to institute what it called a “defensive lockout” to “jumpstart the negotiations,” and then it chose to wait for more than a month before coming back to the table to bargain over economics. The league chose to talk about competitive imbalance when it seems obvious that it has a more significant problem with competitive integrity—with ensuring that teams are trying to win rather than wring out surplus value. As the players made clear moves toward compromise earlier this month—lightening what they were asking for with almost every proposal—the league budged far less and waited far longer to move on many of its key points. It was easy to come away from the whole thing feeling that the league’s priorities were maximizing profit first, breaking the strength of the union second and anything related to holding an actual baseball season perhaps a very distant third. It’s fair to say that no one should be surprised by that. But it’s also fair to note that it was a clear, deliberate choice on the part of the league, and a telling sign of how the owners see their role—just like the clear, deliberate choice to cancel games on Tuesday.

In the end, Manfred’s most telling line today might have been the last one he said. The final question of the day came from Ken Davidoff of the New York Post, who asked if there was anything Manfred regretted doing or not doing over the five years since the last CBA, a period of time in which players have grown increasingly and vocally upset with the state of the game.

“Throughout the five-year period, there was a lot of rhetoric about dissatisfaction with the deal that they made. A lot of the rhetoric was negative with respect to clubs, the commissioner's office, me,” he said. “That environment someone else created, and it's an environment in which it's tough to build bridges.”

That environment someone else created. Baseball is an ecosystem; all the various parts work (or are supposed to work) in harmony. It’s impossible to assign blame or credit for anything to any one person, and by default, there’s a lot of synecdoche. Manfred neither works on his own nor for himself: The 30 owners are his 30 bosses. If he truly believes that someone else created this environment, fine. But as he looks at a game locked out, players furious, fans disappointed or heartbroken or, worst of all, finally turning apathetic—this is the institution he leads, and this is the environment it is in. If he wants to say it was created by someone else, perhaps he should let us know whose responsibility he believes it is to build a new one.

More MLB Coverage:

• Derek Jeter Is a Player Again

• Rob Manfred’s Argument About Owning an MLB Team Is False

• Baseball’s Greatest Threat Isn’t the Lockout

• Andrew Miller Explains Key Lockout Issues for MLBPA