Lessons of a Life Well Lived: My Friendship With Roger Angell

News of the death of Roger Angell jarred me like a thunderclap. Shock may seem incongruous with the passing of someone who was 101 years old with clear memory of Babe Ruth in his camel hair coat walking the streets of Manhattan. As Michener’s Gray Wolf tells his adoptive son in Centennial, “Only the rocks live forever.” But the brutal finality of it—the best, most eloquent, most observant baseball writer who ever lived and an inspirational friend suddenly gone—arrived without mitigation from age.

Only last month, amid the baseball ecumenism that is Opening Day, we talked by telephone, bound by the timeless hope of what another season might bring. Roger was particularly excited about the Mets, the latest in a connoisseur’s string of adopted teams that tickled his baseball bones (starting with Carl Hubbell’s Giants as a child and then Willie Mays’s Giants, through the Shakespearian, accursed Red Sox given his nine decades of summering in Maine, through Walter Haas’s A’s and Joe Torre’s Yankees.) He told me he had enjoyed taking in a spring training game in Sarasota in March with his wife, Peggy Moorman, which would turn out to be his last sojourn to a ballpark.

“It was a great day,” Peggy says. “I always keep score. If he wants to know what somebody did his last time up, I have it. His eyesight was not good. But from just a little bit of movement he could pick up from the field, and from what he heard, he could tell exactly what was going on. It was amazing. I told him, ‘You know, you are very freaky!’”

The thunderclap of the news Friday still echoed in me when the car radio played Vivaldi’s Concerto in A Minor. The violins rose and swooped like young hawks on summer thermals. The piece is 311 years old. It made me think of Roger. Forty-seven years after he wrote “Agincourt and After,” a literary concerto about the 1975 World Series—the writer and baseball at the top of their games—the piece still crackles with brilliance, just as it will after 311 years. Gray Wolf was almost right. Like the rocks, the classics also live forever.

Ending “Agincourt and After” in The New Yorker and placing himself in the account as he usually did, Roger wrote, “I left soon, walking through the trash and old beer cans and torn-up newspapers of Jersey Street in company of hundreds of mourning and tired Boston fans. They did not look bitter, and perhaps they felt, as I did, that no team in our time has more distinguished itself in the World Series than the Red Sox—no team, that is, but the Cincinnati Reds.”

Not even the best of writers gets to write the ending of their lives. But somehow, had Roger sat down at his typewriter with a pair of scissors and Scotch tape—the way he wrote before word processors, genius pouring out in essentially a first draft—the end he crafted might have resembled what did happen.

It was last Wednesday evening. Roger and Peggy were watching the Mets play the Cardinals on the television in their New York apartment. At 101, despite vision, mobility and congestive heart issues, Roger for the past six weeks—since the start of baseball again, really—was as alert and observant as ever. He and Peggy even had talked about returning to their beloved Maine this summer. He dressed smartly every day, even as the physical machinations of it grew difficult. When Peggy suggested a robe and pajamas would suffice for a day at home, Roger harrumphed, “I would rather die.”

“I told him, ‘You don’t have to look so elegant every day,’” Peggy says. “But he did. He was the same old, beautiful Roger.”

Peggy did hire at-home assistance. It was during the Mets’ game last Wednesday that a nurse visited, interrupting their baseball watching. Peggy had noticed that Roger had become less alert that day. He was weakening. He could barely speak. There was not much the nurse could do other than comfort him.

After the nurse left for the night, Roger, with great effort and little volume, managed to say something to Peggy.

“Sco-”

Peggy drew nearer. Roger rallied the energy again.

“Score. Check the score.”

Peggy checked the score.

“The Mets won, 11–4,” she said.

Those were the last words Roger Angell spoke.

Peggy and their beloved fox terrier, Andy, watched over him for the next 36 hours or so, until Roger took his last breath.

“In every way it was beautiful and peaceful,” Peggy says. “And the last time he spoke, it was about a baseball game. It was an 11–4 Mets game.”

Like Vivaldi, the works of Roger Angell will not just endure but also grow in their majesty because time is the ally of genius. Roger so perfectly fit the rhythm and rhyme of baseball that it is hard to believe that he did not start writing regularly about the sport until he was 41 years old. It was 1962. William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, wanted to sprinkle more sports into the magazine. He also wanted writers to write about what interested them, because he knew passion is the secret ingredient of all forms of crafted literature.

“You know about baseball?” Shawn asked.

“A little bit,” Roger replied.

“Why don’t you give it a try? We don’t want it to be sentimental and we don’t want it to be tough.”

He fit the space as perfectly as the wooden Beetle Cat he first sailed during his early idyllic summers in Brooklin, Maine. (The dinghy was first designed and built in 1921, the year after Roger was born.) He remained true to Shawn’s vision. Never sappy and never mean, he operated on empathy, extraordinary observant powers and a pilot light of curiosity the years never dimmed. He put himself in the stories not out of ego but wonder. Like a kid in Willy Wonka’s factory, he was beguiled by the game and especially the people who had stories to tell. Nobody taught him the way. With passion as his lamp, he just did.

One of the most beautiful and powerful requiems ever heard was written by the anticlerical if not outright agnostic Giuseppe Verdi. Perhaps the very nature of not being devout gave Verdi the outsider’s eye to score such magnificence for a Catholic funeral mass. In the same way, unencumbered by journalism school (he cut his writing teeth with a GI newsletter during World War II) and without the detached training of baseball beat writing, Roger dove in without rules or norms. The twin luxuries of having time and space allowed his mind and talents to soar.

Like so many others in the wake of his passing, I could go on about the beauty of his writing. Greatness is making the difficult look easy. Roger defined it with writing.

But here I must diverge, like tacking against the wind in a Beetle Cat. Put writing aside, if that is even possible with Roger. Just as enduring, though less celebrated, are the lessons he taught us about living well and aging well, no matter the calamities that might come in waves like hailstorms. That is why his death hit me in a thunderclap. Roger, as he so loved his subjects to do with him, shared his story with me.

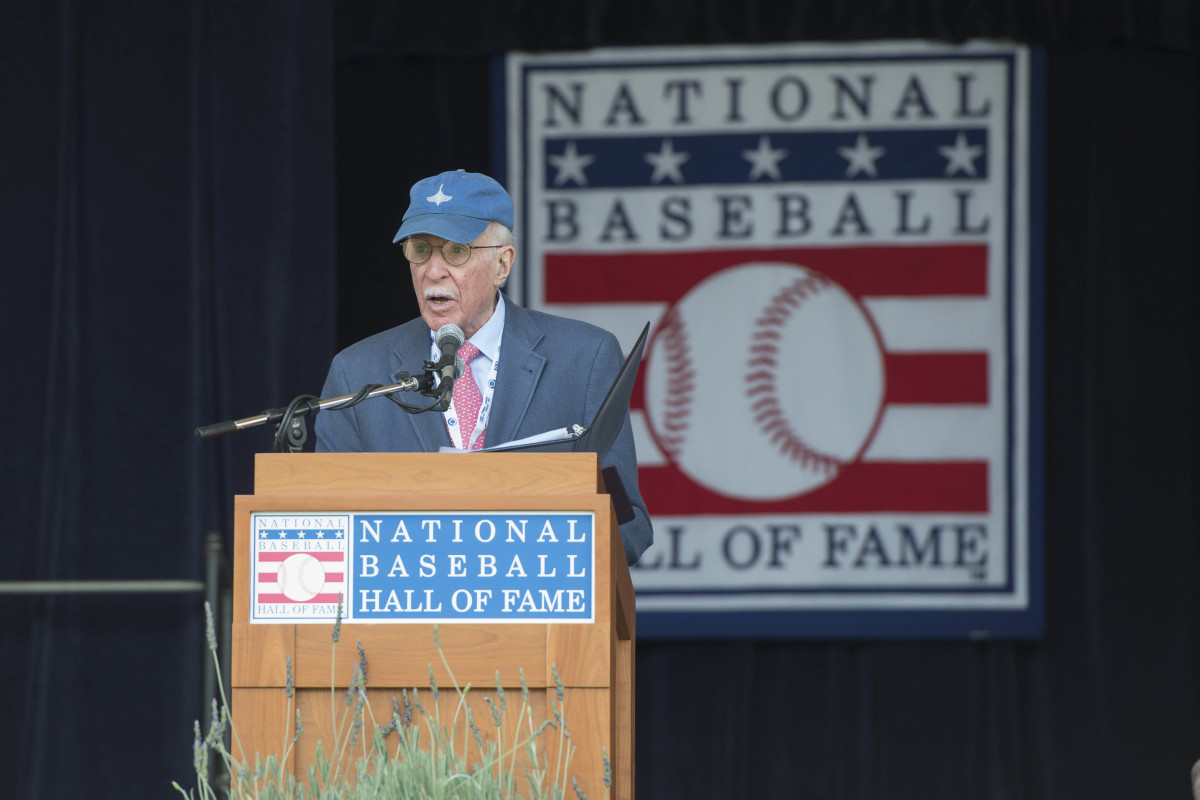

It was 2014. Roger was 93. He was about to be honored by the Baseball Hall of Fame as that year’s winner of the Baseball Writers Association of America’s highest honor. I asked him if I could write a feature about him. He responded with complete graciousness of time (in New York, at the ballpark and in Maine) and thought.

This job is a blessing. From Sandy Koufax to Tony Gwynn to Mike Trout, I have enjoyed the privilege of conversation with the best in the world at what they do. None moved me quite like Roger, not just because of shared loves of writing and baseball, but also because of how much he shared.

“What’s so interesting to me,” he told me, “is in writing about baseball the number of people I talked to who really gave their lives to me. They were willing to give me their lives.”

Such responsibility moved me profoundly, especially because Roger, at 93, was giving me his life—so giving that he drove me to the gravesite and headstone that was awaiting him at the Brooklin town cemetery, right there next to the graves of his second wife, Carol, his mother, Katharine, and his famous stepfather, E.B. White (nicknamed Andy; yes, the fox terrier is named after the author of Charlotte’s Web), and near the gray granite markers of his brother, Joel White, and his daughter, Callie. His gravestone lacked only the four digits after the hyphen.

The result was a story that ranks among my personal favorites, especially given the friendship it germinated. The telephone tethered us often enough. When I called on his 100th birthday, he delighted in describing how he celebrated with cake and champagne.

We giggled together about how writers in the press box now are consumed with their screens (social media, video highlights, solitaire for goodness gracious) and how fans will stand in long lines for food while the game is going on. How is it, we wondered, that this beautiful daily puzzle that is baseball does not deserve our undivided attention?

“The thing about baseball,” he told me, “is the pace of it is just right for a writer. It’s linear. It really is linear, unlike the other sports. Something happens and another thing happens. You can see what leads up to something and what leads away from it. You can see games changing, and it happens at a pace where you can think about it and write down what it looks like and remember it that way.

“All the other sports things are happening, but there’s a lot of flow and a lot of compacted things that are happening at the same time. They are much more of television sports and replay sports than baseball.”

What struck me most about Roger was how perfectly content he was in this pocket of his late life, even with deaths of family and friends piling up and the warranty on body parts well past their expiration dates. Only with this kind of self-satisfaction that plumbs the very soul, I thought, does one show a visitor his final resting place.

That same year, Roger wrote what may be his best piece, and it had nothing to do with baseball. “This Old Man” was the unblinking gaze into a mirror by a man in his 90s. Though Roger stayed true to his avoidance of sentimentality, it dripped with honesty while addressing the ravages and blessings of age. Based on our time in Maine, one line stood out to me regarding late life happiness: “We’ve outgrown our ambitions.” At that age, contentment is a most comfortable pillow.

“It’s had an amazing response,” Roger told me in his cozy Maine house, surrounded on three sides by water. “The biggest response of anything I’ve wrote—by far. Huge. Hundreds. Well over a hundred handwritten letters and something like 40,000 emails.

“It wasn’t just old people. It was young people, too, for some reason. I don’t think somebody my age had written a lot about some of the things I wrote about or put out there what it’s like to be old.”

Then he lowered the volume of his voice.

“I also got several proposals of marriage, but don’t put that down.”

“Seriously?” I replied.

“Oh, yeah.”

“The power of the written word.”

“What do you mean? It’s the power of the charm. Now, you’ve hurt me.”

“And here I was thinking I was complimenting you.”

We laughed.

“Was that story assigned to you?” I asked.

“No, I wrote a piece the year before about the death of my wife,” he said. “And the reason I was able to write personal pieces was because of Tina Brown. She did urge people to write their own stories. She always said to me, ‘Roger, you’ve got a lot of wonderful stuff to write about. Write about it.’

“My instinct was to be the typical uptight WASP and not write about family, not write about personal things. But I did. I wrote a book about my stepfather and my children and my wife, and a lot of different stuff. And after Carol died, I wanted to write about that in some way. And then later on I started to realize I really am getting old. And I was scared about writing that. I didn’t know how to write that. I wrote in little chunks, little pieces of things which I put together. I was very unsure even at the end if it was going to work.”

“This Old Man” is his “Four Seasons,” his magnum opus. It is that good. It is that achingly sweet, never more so than in this interior examination that likely launched the marriage proposals:

Getting old is the second-biggest surprise of my life, but the first, by a mile, is our unceasing need for deep attachment and intimate love. We oldies yearn daily and hourly for conversation and a renewed domesticity, for company at the movies or while visiting a museum, for someone close by in the car when coming home at night.

I believe that everyone in the world wants to be with someone else tonight, together in the dark, with the sweet warmth of a hip or foot or a bare expanse of shoulder within reach. Those of us who have lost that, whatever our age, never lose the longing: just look at our faces. If it returns, we seize upon it avidly, stunned and altered again.

The story won the prize for Essays and Criticisms awarded by the American Society of Magazine Editors. More importantly, that same year, 2014, two years after the death of Carol, Roger married Peggy, an accomplished author in her own right. Stunned and altered again.

Peggy was with Roger when they opened their Maine home and their lives to me and my wife. Their love was as obvious as the sun setting over Eggemoggin Reach, its golden light glistening off the gently bobbing water with theatrical brilliance and illuminating the western-facing windows of their 101-year-old wooden home. That such a love and a place could still be found in this world soothed the soul, no matter the age—better still, because of age. Beyond written words, however elegant, these are the lessons of a life well lived. It is what Roger taught us to his last breath.

It occurs to me that I should ask Peggy, so gracious and personal in sharing her loss, if I could write about what she had told me about his last moments.

“That’s kind of you to ask,” she says. “I am talking to a writer, after all.

“You know? Yes. I would like that. You should.”

Roger once wrote a piece about the famously ornery pitcher Bob Gibson. Gibby invited him to his home for three days and opened up like never before. After the piece appeared, Gibson sent a picture of himself to Roger, writing, “The world needs more people like you.” In 1981 he wrote about a semipro pitcher in Vermont and his girlfriend, a poet named Linda Kittell who had been writing “endless letters about baseball” to Roger. She was the one that gave him that line that underpinned his writing pursuits: “We’re giving you our lives.”

I thank Peggy. She is paying forward this trust.

“I am so thankful that right to the end Roger was Roger,” she says. “Smart and brilliant and interesting … and still the handsomest man in any room!”

Goodbye, friend. Eternity awaits in that Brooklin plot and in your writing. Few earned it so long and so well.

More MLB Coverage:

• SI Vault: The Passion of Roger Angell

• Nobody Did It Better Than Roger Angell

• Are the Mets Fundamentally Cursed? This Is the True Litmus Test.

• Five-Tool Newsletter: Thank You, Joe Panik

• Albert Pujols Is Having the Time of His Life