The Science Behind the Rise of the Slider

Welcome to The Opener, where every weekday morning during the regular season you’ll get a fresh, topical story to start your day from one of SI.com’s MLB writers.

On June 1, holding a 4–3 lead in the 11th inning at Texas, Rays manager Kevin Cash asked righthander Matt Wisler to close the game. Wisler, 29, is a former failed starter who was traded, waived or designated for assignment seven times in seven years before landing with Tampa Bay last season. He is a different pitcher from most of those travels, and he showed why in pitching a 1-2-3 inning to lock down the save.

Wisler threw the Rangers 14 pitches. Each one was a slider. On the heels of his previous outing, that marked 19 straight sliders from Wisler.

Cash used Wisler again two days later, this time in the seventh to protect a 4–2 lead against the White Sox. In throwing another scoreless inning, Wisler threw 25 pitches. Again, each one was a slider.

Wisler next pitched four days later with another scoreless inning, this time against St. Louis. He started that outing with 10 straight sliders before finally throwing a four-seam fastball.

Wisler threw 54 consecutive sliders. Hitters remained flummoxed. They went 0-for-9, four by strikeout.

The slider is the nastiest pitch in baseball. If you want to know why it’s harder to get a hit this year than in any season since the mound was lowered in 1969, take a cue from Wisler: lean heavily on the slider.

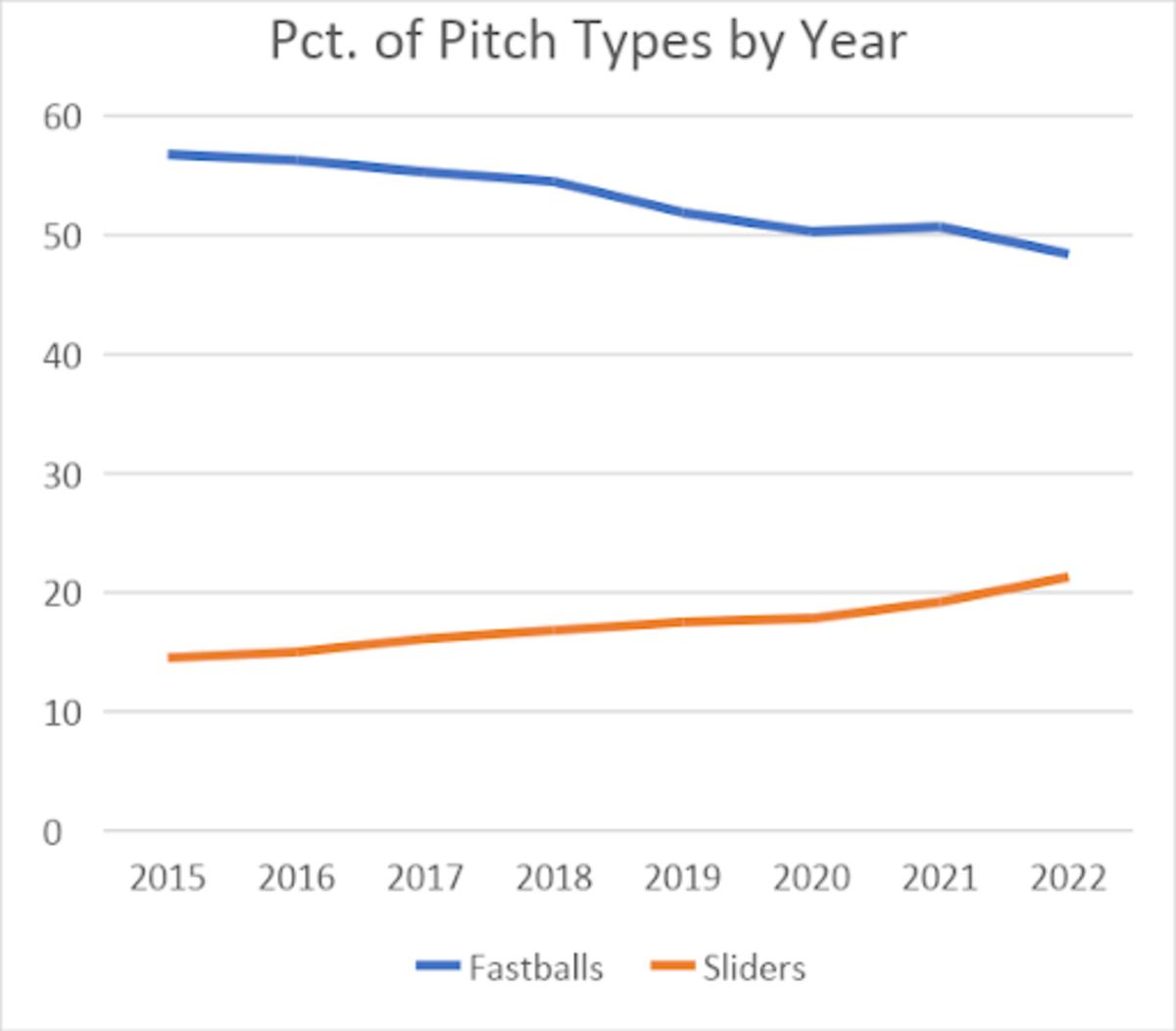

Batters are hitting just .209 against the slider, the lowest mark against any of the five pitches thrown at least 2% of the time. Pitchers and their coaches are following the data. For the first time in recorded history, fastballs (not including cutters) are being thrown less than half the time. Since 2015, which marked the start of the Statcast Era, fastball use has declined from 57% to 48%. Almost all that decline can be accounted for by an increase in sliders.

Slider usage has increased eight consecutive years, but the increase has been especially marked in each of the past two seasons: up 1.4% last year and up 2% this year. This chart leaves no doubt about the steadiness of this trend:

Why is this happening? Despite the fascination media and fans have with velocity, velocity has far less influence on run prevention than spin. So, even with heaters increasingly hitting triple digits these days, an average slider is harder to hit than an elite fastball.

Wrap your head around that for a minute. Now keep in mind that four-seam fastballs thrown at 97 mph and above are still rare. Only 10% of all four-seamers are clocked at such high velocity. And yet the average slider grades out as the better pitch:

MLB 2022 | AVG | SLG |

|---|---|---|

Four-seamers 97+ MPH | .211 | .355 |

Slider | .209 | .344 |

But it’s not just the volume of sliders that’s on the rise—it’s the quality. Thanks to high-tech pitching labs and coaches skilled in biomechanics, pitchers are throwing more efficient sliders. The average slider spins 14% faster today than it did in 2015. Even the crackdown on sticky substances has had little effect on slider spin (down just 1% of its height in 2020).

Moreover, in that same time pitchers have added five inches to their extension on sliders—the point where they release the pitch. Almost all that extra extension has come in the past three seasons, as labs have proliferated. More extension means less time for a hitter to react and more finish on the break of the pitch.

This is all bad news for hitters. More volume. More spin. More extension. More pitchers getting on the slider bandwagon.

Slider success stories are everywhere. Unlike the curveball or changeup, which require more feel, the slider is easily taught. The Mariners have virtually an entire bullpen made up of slider specialists. Only the Giants, Reds and Royals throw more sliders than Seattle, which boosted its staff’s slider use from 16.5% last year (22nd in the majors) to 27.2%.

Pick any night and virtually any game and you will find a slider success story. From Cy Young winners to journeymen, here are just a few of them:

Edwin Diaz: Though the Mets closer is throwing his fastball at a career-high velocity (99 mph), he’s throwing fewer of them ever (45%). After throwing a career-high 38% sliders last year, he’s pushed that usage to 55% this year. Why? Follow the data. Hitters are hitting .297 against his fastball and .171 against his slider.

Jakob Junis: What the Timberwolves are to three-pointers and what the Bucs are to pass attempts, the Giants are to sliders. No team throws more sliders than the Giants. Nearly one out of every three pitches they throw is a slider (32%). They are the first staff in the Statcast Era to throw more than 30% sliders. After signing with the slider-loving Giants, Junis has bumped his slider usage from 40% to 53%, the highest rate of sliders among all starters. The Giants also added 2 ½ inches of his extension at that pitch. They also looked at the metrics of his four-seamer from last year (.593 slug, .714 expected slugging) and told him, “Don’t throw that pitch anymore.”

Clayton Kershaw: There used to be a macho mentality when it came to throwing fastballs. Pitchers had to “establish” their fastball, “challenge” hitters with their fastball and use the fastball to “set up” their breaking pitches. Modern convention laughs at such outdated thinking. It was Kershaw who paved the way. Kershaw has not thrown 50% fastballs since 2015.

If the best pitcher in baseball could throw his fastball less than half the time, why couldn’t others? As Kershaw ages he is leaning even more into his slider. Over the past two seasons the Dodgers’ lefthander has thrown 47% sliders, and hitters still have trouble with it (.208).

Hunter Greene: He averages 98.5 mph on his fastball, but it gets hit (.710 slug) because it lacks proper spin and command. It’s the best evidence that hitters can time any fastball, no matter how hard. But the slider is flat-out nasty (.134 batting average), which is why Greene throws it a whopping 44% of the time. On May 15, Greene threw 65 sliders, the most by a pitcher in any game over the past three seasons.

Shane Bieber: Only five pitchers have snapped off more sliders this year than Bieber: Dylan Cease, Robbie Ray, Greene, Wisler and Logan Webb. Bieber has boosted his slider usage from 26% last year, which had been a career high, to 35%. Batters are hitting .308 against his fastball and .184 against his slider.

Robbie Ray: He is another Cy Young winner gone slider heavy. After a career high 31% sliders last year helped him take home the Cy, Ray has increased that rate to 39%. Batters are hitting .188 against it. Even more impressively, Ray has added six inches of extension to his slider since 2017. His extension on the pitch has improved each of the past three seasons.

Carlos Rodon: The slider has been his calling card ever since the White Sox took him with the third overall pick of the 2014 draft. Of course, once he signed with the Giants, Rodon has leaned into it even more. Rodon has bumped his slider usage from 27% to 32%. Since July 29, 2020, including the postseason, Rodon has thrown 1,111 consecutive sliders without allowing a home run on the pitch. The batting average against Rodon’s slider over that time is .147.

Steven Okert: The lefthanded reliever always had a good slider. He just never threw it enough. From 2016-18 with the (pre-slider crazed) Giants, Okert held batters to a .128 average on his slider but threw it only 21% of the time. He was stuck in the traditional mode of pitching, throwing his fastball 51% of the time and getting beat on it.

The Giants dropped him from the 40-man roster just before the 2019 season. He spent the entire year in Triple A. He was unsigned throughout 2020, the shortened COVID season. The Marlins signed him to a minor league contract in February 2021. Four months later, he made his first major league appearance in three years. He came back a different pitcher. Okert threw his slider 60% of the time last year and has boosted it to 71% this season. This new version of Okert is 8–1 with a 2.56 ERA with the Marlins.

For the ultimate slider success story, we must return to our Sultan of Sliders, Wisler. Originally a seventh-round pick by the Padres, Wisler was traded to the Braves in the Craig Kimbrel deal. He broke into the big leagues as a starter pumping in 94 mph fastballs 62% of the time. He was going nowhere. Wisler was 16–23 with a 5.27 ERA with the Braves, who traded him to the Reds, who DFA’d him and sent him back to the Padres, who DFA’d him and sold him to the Mariners, who waived him. That’s when his career took a sharp upturn.

His fifth team, the Twins, claimed him on waivers and, with the encouragement of pitching coach Wes Johnson, turned him into an elite slider specialist. They also told him to forget throwing his sinker, a pitch he once threw 41% of the time. He hasn’t thrown one since. Throwing 70% sliders with the Twins, Wisler posted a 1.07 ERA in the small sample (18 games) of the COVID-shortened season.

But Minnesota didn’t believe enough of what they saw. The Twins non-tendered him.

The Giants (of course) signed him for $1.15 million. But they, too, quickly gave up on him. Wisler was throwing 90% sliders with a 6.05 ERA over just 19.1 innings when San Francisco became the fourth team to DFA him. After a slow start, Wisler was pitching well in his last nine games for the Giants (two runs, two walks, 14 strikeouts in 10.1 innings). San Francisco traded him to Tampa Bay (of course). The Rays most represent the philosophy of modern pitching: throw your best pitch often. Don’t worry about “set-up pitches.” Don’t be hidebound by throwing more than 50% fastballs. The Rays are throwing just 38% fastballs this year. No other team is less than 44%.

Wisler made his debut with the Rays, his seventh team, on June 13, 2021. Since then, he has thrown 92% sliders. Batters have hit .214 against his slider, even though they know with near certainty what is coming. (Wisler varies the shape and break of his slider, so there is some variety.) His ERA with the Rays is 2.48. Since his transformation with the Twins, Wisler is a completely different pitcher:

Wisler Career Stats | W-L | ERA | Games | IP | K/9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2015-19 | 19–27 | 5.20 | 129 | 389 1/3 | 7.0 |

2020-22 | 5–8 | 2.78 | 98 | 110 | 10.3 |

A generation ago, Matt Wisler might never have had this second stage to his career. At age 26, he was staring at a similar fate as middling starting pitcher doppelgangers such as Jose Silva (5.37) and Rich Yett (4.95), who were done in the majors by 28. But we know so much more about how to defeat the swings of hitters, especially out of the bullpen. Limit exposure. (Wisler has not faced a batter for the second time in a game in two years). Spin the baseball. Remember that an average slider is harder to hit than an elite fastball.

The slider saved his career. As any frustrated hitter can tell you, he is far from alone.

Watch MLB games all season long with fuboTV: Start a 7-day trial today!

More MLB Coverage: