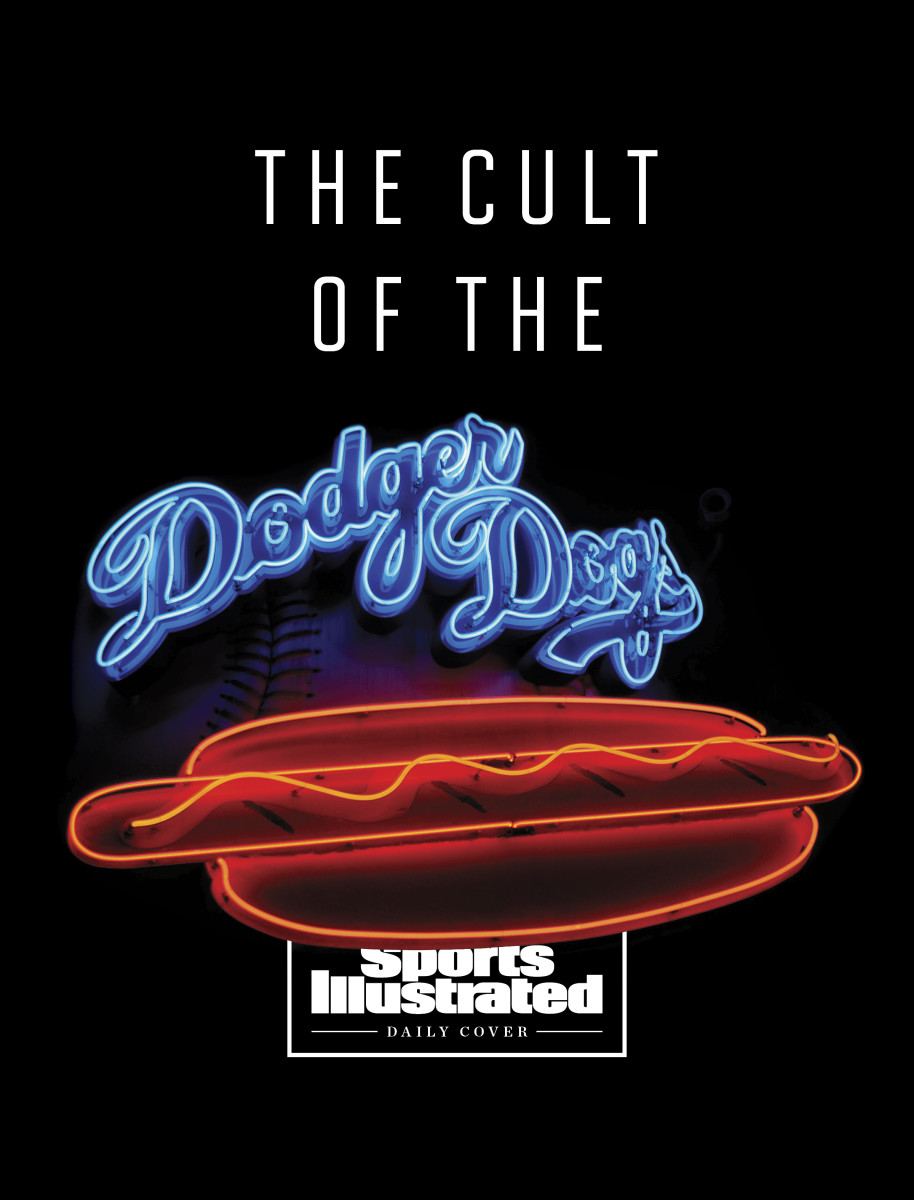

The Most Iconic Hot Dog in Baseball

Consider the Dodgers’ dominance of the last decade. Since 2013, they’ve been the most successful team in baseball, the only club in that stretch to post a winning percentage above .600. They’ve led MLB in attendance in each of those seasons. In just about every metric—wins, payroll, various forms of fan engagement—they have made a habit of sitting atop the league.

And one more: The Dodgers sell more hot dogs than any other team. By a lot.

It helps, of course, to have those league-leading attendance totals in the biggest stadium in baseball. But it’s not just a numbers game. It’s also the legacy of the Dodger Dog—a signature that has been with the team as long as it has played in Dodger Stadium, with a history as entwined with the club as Vin Scully, Sandy Koufax or Clayton Kershaw. There have been a few changes over the years. Some have been twists made to the classic (kosher dogs, veggie dogs, chili-and-jalapeño-laden “Doyer Dogs”) and some have been moves behind the scenes: This is the first season with a new producer, Southern California sausage company Papa Cantella’s, after the Dodgers could not reach a new agreement with their longtime meat partner, Farmer John’s. But the core idea here remains the same. The Dodger Dog is the most iconic hot dog in baseball—which has helped make it the most popular, too, and it’s not close.

Here are the numbers: Heading into this season, the Dodgers were projected to sell three million hot dogs this year. That represents an uptick over recent years, but not a dramatic one, after the team averaged 2.7 million dogs from 2015 to ’19. (Those are the last seasons with full league hot dog data available for comparisons—the various pandemic restrictions across baseball complicate dog-tracking for ’20 and ’21.) In other words, three million Dodger Dogs this year would be roughly in line with business as usual at Chavez Ravine. As for the team projected for second place in the hot-dog wars? The Yankees … at 1.2 million. That means no one else is expected to sell half as many hot dogs as the Dodgers. Which checks out: No team averaged more than 1.4 million hot dogs a year between ’15 and ’19. While the Dodgers have been pushing three million, only a handful of teams have consistently been able to clear one million, and none have approached two million. (The Yankees are joined in the Million-Hot-Dog Club by the Cubs, Guardians, Rangers, Giants, Cardinals and Red Sox.) This isn’t just a win for the Dodgers. It’s a beatdown.

Those numbers come from the king of hot dog data: National Hot Dog and Sausage Council president Eric Mittenthal. (He holds a joint appointment with the North American Meat Institute as chief strategy officer.) He estimates that Dodger Stadium accounts for 15% of MLB’s yearly hot dog sales. This means that more than three of every four people who visit end up getting some form of Dodger Dog—a hot-dog attraction unmatched anywhere in baseball.

Is Dodger Stadium the individual building that sells the most hot dogs in the U.S.? Sadly, there are no firm numbers on this. (At least not any tracked by the National Hot Dog and Sausage Council.) It’s clear from the existing data that Dodger Stadium easily beats out all other U.S. sporting facilities. But when it comes to all buildings, there might be some competition from that other most iconic of frankfurters: The Chicago Dog. “O’Hare Airport sells a lot of hot dogs to millions of people coming through each year,” Mittenthal says, though he reiterates he cannot be exactly sure of how it stacks up to Dodger Stadium.

The Dodger Dog is 10 inches of 100% pork. (If you want 100% beef, you go for the Super Dodger Dog, and a plant-based version is available, too.) The story goes that the name came from longtime Dodger Stadium concessions manager Thomas Arthur: When he took the gig for the ballpark’s inaugural season, in 1962, he’d originally considered marketing these hot dogs as foot-longs, but he didn’t want anyone to complain about the missing two inches. It seemed better to go with truth in advertising and call them something else. The right name would be something catchy, something pithy, something that sounded as good being shouted out by a vendor as it would in an advertisement … and the Dodger Dog was born.

The hot dog was already synonymous with baseball by the time the Dodgers moved west to L.A. The two had enjoyed twin increases in popularity as the 19th century turned to the 20th: Baseball stepped into its role as the national pastime as it became professionalized, and the sport found its perfect match in hot dogs, which had already been growing common at fairs and as street food. The hot dog represented everything a turn-of-the-century American could want: “You had meat in a convenient package you can carry around,” says Bruce Kraig, one of the nation’s leading hot dog historians and the author of Hot Dogs: A Global History and Man Bites Dog: Hot Dog Culture in America. (Yes, the hot dog offers enough material to fill one book, and then another.) As baseball grew, the hot dog was right there along for the ride.

The Dodger Dog came around more than half a century later. But it managed to unlock new potential and reach previously unseen heights.

One factor is the size. There’s nothing special about a regular six-inch dog. On the other hand, a foot-long can sound, well, long. There’s real success to be found with something in the middle. A 10-inch Dodger Dog works because it taps into an old finding from Oscar Mayer: People are more receptive to a hot dog if it is slightly longer than its bun, Kraig says. It makes them feel like they’re getting more bang for their buck, and it’s aesthetically pleasing, besides. The fact that the Dodger Dog was the perfect length set it up for success from the start.

Another is the name. It might seem like a small detail. But to make a hot dog at a ballgame something more than a meal—to make it feel like a destination unto itself—it needs some kind of catchy branding. “It just sounds good,” Kraig says. “Dodger Dogs, it’s alliterative. It works.” (That’s a tried-and-true move: He points out that the closest analog to a Dodger Dog is a Fenway Frank.) Without a name, it’s just a hot dog. With one? It can be an icon.

And much of the rest is tied to circumstance. To sell three million hot dogs a year, it helps to play in the biggest stadium in baseball, and it helps to have a team good enough to fill it day in and day out. It helped that the original producer, Farmer John’s, chose to sell Dodger Dog hot dogs in local supermarkets for years—strengthening the brand awareness. (The new producer, Papa Cantella’s, has also begun selling them in stores.) It helps to have been around for decades, even as the original has been tweaked and expanded on, to have an established role as an integral part of the ballgame: A Dodger Dog is not an optional add-on to the stadium experience. It is the experience.

A few hours before Monday’s Home Run Derby, the vendor is busy, straightening up her station. She has sold Dodger Dogs here at the stadium for 20 years now. (Citing strict instructions for vendors not to speak to the media given ongoing labor tensions, she declines to give her name but agrees to chat, anyway.) It’s changed, she says: It used to seem like she saw the same customers all the time, season-ticket holders and other regulars that she recognized, coming up for a hot dog night after night. Now, there are more people who tell her this is their first time.

“People say they come from out of town just for the Dodger Dog,” she says.

She doesn’t know what the numbers were like when she first began selling two decades ago. But it seems to her like they’ve only gotten more popular. On a good night, she’ll now sell 1,400 Dodger Dogs per game, she says, with close to an even split between the traditional dog (pork) and the super dog (beef).

“It’s iconic,” she says.

And maybe put best by one of the participants in the celebrity softball game on Saturday:

“There’s something about the environment of being here at Dodger Stadium and seeing that Dodger Dog sit there, with mustard on it, relish, some onions,” said actor Bryan Cranston. “You know what it’s like? When you go to a movie theater, you have to have popcorn. You’ve got to have popcorn. When you come to a Dodger game, you’ve got to have a Dodger Dog.”

Watch MLB All-Star Week at Dodger Stadium with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

More Baseball Coverage

• Facing an Uncertain Future With the Nationals, Juan Soto Keeps Smiling

• The Nationals Have a Juan Soto Dilemma

• The Nationals Need to Make the Most of Their Time With Juan Soto

• MLB Players Have Some Ideas on How to Improve All-Star Week

• ‘A League of Their Own’ Endures Because It’s Personal