Aaron Judge: The Authentic Home Run King

Sometime in this Summer of Judge, when Aaron Judge was passing Yankees legends like they were billboards on a highway, New York hitting coach Dillon Lawson made certain that he and Judge took one moment to appreciate history in the making. Judge had just hit another home run at Yankee Stadium, one of so many big moments. Lawson confesses he can’t remember the historic name surpassed on this one.

Judge returned his helmet to the bin over the bat rack. The two of them smiled. Lawson felt compelled to speak.

“You know, a lot of these legends have passed on, and these are their records you are breaking,” Lawson told him. “We talk about them all the time. And you know what? I’ll be gone, my kids will be gone, and people are still going to be talking about you. That is amazing. Incredible. Not that you need me to say anything, but it’s unbelievable.”

Judge smiled that sheepish smile of his, the one that gives away the little boy’s humility in him, engrained forever by his schoolteacher parents, Pat and Wayne, and a feature so sweet as to be even more of an identifier than being 6'7" and 282 pounds.

For one small slice of time, the slugger and the coach stopped to enjoy the incredible view, like Hillary and Norgay in May 1953, stopping to breathe the thin air and absorb the vista as they make their way to the summit of Everest.

Ruth, Mantle, Maris ... these are the names—ghosts, even—that also have been at Judge’s side all summer. Not long after Lawson acknowledged them in their midst, I asked Judge about keeping and surpassing such company.

“I pinch myself,” he told me. “It’s pretty surreal when you think about the Yankee greats and baseball greats. Any time you’re mentioned in the same sentence as them or ‘you’re on a pace for this,’ it’s mind blowing for me because these guys are on another planet. The things they did in this game and accomplished, I’m still trying to work to that. It’s tough for me to describe how I feel about that. It’s surreal.

“I never try to think about the record books or being in the same sentence as those guys because my mind is always on championships.”

Now it is our turn to stop and admire baseball history on a scale bigger than anything in generations. Tuesday night in Texas, Judge officially joined the pantheon of baseball immortals. No more talk about “pace.” No more talk about “chasing.” He hit home run No. 62, clipping a hanging slider from Rangers right-handed pitcher Jesús Tinoco into the left field seats at Globe Life Field with that balanced, metronomic swing that belies his giant levers.

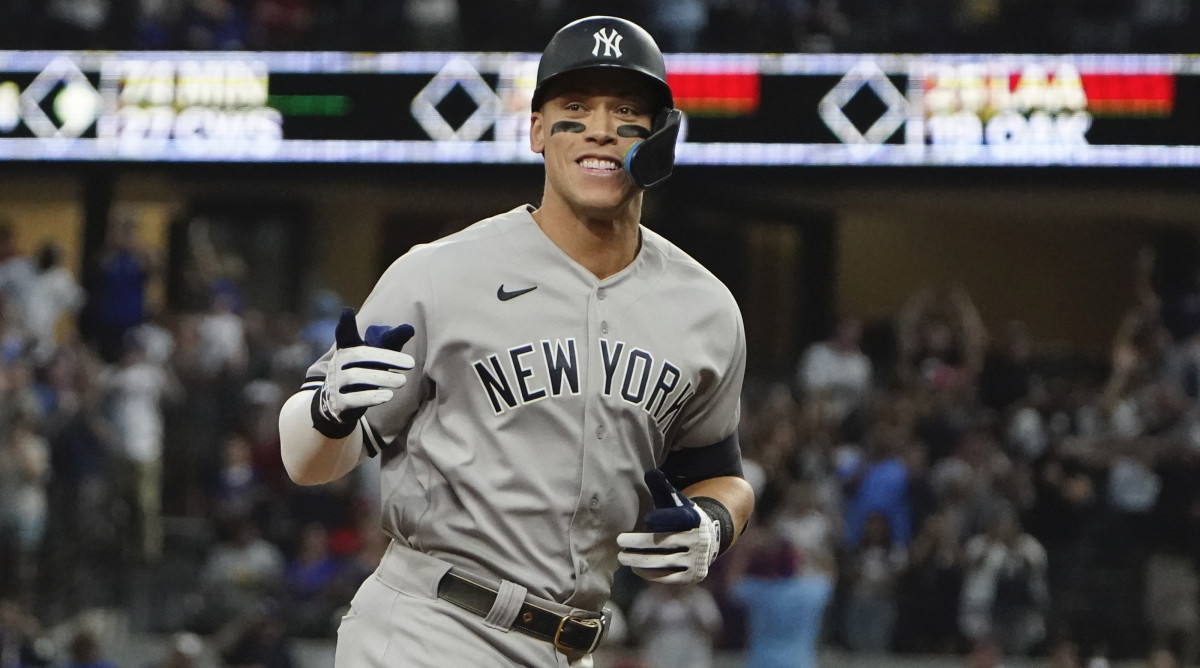

Fittingly, as much as the swing itself, what will linger from that moment is that little boy smile of his around the bases, full of wonder and joy. And doubtless also in that smile was relief, as it took 23 plate appearances over six long days since he tied Roger Maris at 61.

Today Judge stands alone. Hello, Everest. He has hit more home runs in a season than anybody in the 121-year history of the American League. Maris’s 61 in 61 had held for 61 years, set so long ago that Major League Baseball didn’t even exist in Texas when he set the record.

No, Judge is not the official major league home run champion. That record belongs to Barry Bonds, with his 73 home runs in 2001—just three years after Mark McGwire hit 70, and back when Judge was 9 years old growing up in Linden, Calif., about 100 miles east of San Francisco.

Either too polite or too unwilling to taint his own wonder years, Judge told me weeks ago there was no doubt about what the record is. “Seventy-three, in my book,” he said. “No matter what people want to say about what happened in that era of baseball, for me, they went out there and hit 73 homers and 70 homers and that’s for me what the record is.”

But here again, Judge stands alone. Bonds is the official home run champion. Judge is the authentic champion. One has the official designation. The other is unofficial but has the prestige of authenticity. Which would you rather have?

Professional baseball, at least what we consider “major league,” dates to 1871. Over those 152 seasons, only seven times has anyone hit 62 home runs. It happened six times in a cluster of four seasons by three men in the heart of the steroid era with no testing for PEDs (Bonds, McGwire and Sammy Sosa).

And it happened once this year, the first time since testing for PEDs began 2003. It is stunning that it happened this year, when hitting is the worst it has been in the 50 seasons with a DH, when the average fastball is faster than ever, when pitchers throw more breaking and offspeed pitches than they do fastballs, when no one else is within 15 homers of him, and when Tinoco was the 230th pitcher Judge saw in 161 games. It took Ruth 10 years as a Yankee to see that many pitchers. Maris saw 270 pitchers in his seven years with the Yankees.

The grind not only of chasing Maris but also of being the singular focus—a place of individual prominence not in Judge’s nature to embrace—wore on Judge. In the past week he kept missing pitches in the zone, usually getting too far underneath the baseball in his eagerness to loft something over the wall, which led to a shower of foul balls set back over the protective netting behind the plate.

Watch Judge and the Yankees live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

So discombobulated was Judge that in the first game of the doubleheader Tuesday he popped out to the infield grass—something he had not done in 1,501 consecutive plate appearances since Sept. 8, 2019. The pop-out came off his bat at a launch angle of 74 degrees—only the fourth time in his career he got underneath a pitch that badly (the others: the ‘19 pop-up in Boston and two in ‘17, his rookie season).

If 61 home runs could possibly seem deflating, finishing the year at that number could have been it, given he was sitting at 59 with 15 to play. With two games left, he needed one more swing to separate himself from Maris and from everybody else who ever played this game without even a whiff of inauthenticity.

And so it was, coming in a perfectly fitting modern way: in a retractable-roofed, $1.2 billion ballpark (the roof was open) in a state without MLB baseball when Maris set the record and against an “opener” from Venezuela, a country from which MLB did not allow a player until four years after Ruth’s career was over.

As home run king, Judge has Ruth’s relative gargantuan size and Maris’s humble career beginnings. Maris was traded to the Yankees from Kansas City in a deal involving Marv Throneberry. Maris was a .249 hitter at the time who had never hit more than 28 homers.

In his debut season, Judge hit .179 and struck out half the time. He overhauled his swing and returned to hit 52 home runs. But injuries kept him out of the lineup 37% of the time over the next three years. Then he dedicated himself to better training and recovery. He cut far back on the sweat equity he invested in batting cages, often out of frustration. He stayed healthy these past two seasons by training smarter, not harder.

“It’s more quality over quantity,” he told me. “It’s helped me out the past two years especially. The most important thing is staying on the field, so if I can save my swings and just get the reps I need. ... Boom! There we go.

“So, it’s just a couple [of swings] off the tee, a little front toss, a little short BP, and then I go straight to seeing some velo, so when I step in the box here I’ve already seen 110 down there and nasty slider down there. So when I step out there it’s ‘Oh, that’s all this guy has? I saw that a hundred times already.’ I think that’s one part of my game that’s really helped me get to the next level.”

As a child, Judge played shortstop and admired Rich Aurilia, the Giants’ shortstop at the time. When he played in his first All-Star Game, in 2017, as he stepped into the box he was star-struck to see Buster Posey behind the plate.

“I was like, ‘I watched you win the World Series with the Giants and now I’m at an All-Star Game with you in the box,’” Judge said. “It was kind of hard not to be a fan in the box.”

Now Judge is the legend. He is the one to which all others after him will be measured. This is his year. It is his record. When you saw the Yankees, one and all, greet him individually with hugs and smiles after 62, you saw a glimpse of his worthiness to hold such an honor. They were happy for the person more so than for the hitter.

“He hasn’t been thrown out of a game here in the major leagues or the minor leagues,” Lawson says. “We talked about that the other day. That’s what he told me. He’s built that way. Part of that temperament plays into the consistency of how quickly he rebounds from adversity. He’s got a really good process. He devotes time. A routine. Being in the right mental space.

“He’s the biggest player on the biggest team in the biggest market. He would not be able to do what he does now if he didn’t devote time to the physical and mental part.”

Asked to pick one word to describe himself, Judge responded, “I would say dedicated. Dedicated to my craft, dedicated to this game. That’s what it’s all about. To get the most out of the short time we play this game you’ve got to be disciplined.”

When I asked Judge about never being ejected by an umpire, he was ready with an explanation.

“I feel like it’s selfish sometimes if you strike out or make an out and start slamming stuff,” he says, “or if I strike out and I’m yelling at the umpire. To me that’s taking away from the team, from my teammate who is about to hit. Hey, I struck out? That’s over with. Ain’t nothing I can do to change it. The umpire’s not going to say, You know what? I was wrong. Aaron made a good point. Do-over. That’s not going to happen.

“If I’m in here slamming my stuff ... because I’ve been in the box and I’ve heard my teammates slamming stuff. You can hear it. I’m in a major league game trying to compete. You can hear that. I never want to take away from the game or take away from my teammates. No single person is bigger than the game.”

True and admirable as such a philosophy may be, today Judge is the biggest person in the game, both in size and influence. Yet the home run king has set himself apart with a commoner’s outlook. He has never fully outgrown what he felt like to pretend to be Rich Aurilia playing shortstop or to take an All-Star at bat in front of Buster Posey.

“I play this game for the fans,” he said. “I’ve got a passion for this, and I’ve got a gift. I do it for them. I do for the kids, rocking my jersey in the stands and one day wishing they’re out there at Yankee Stadium. That’s what it’s all about: trying to inspire kids to do something special with their life, whichever avenue they go.

“Accomplishments? I want to be a World Series champion. Not only once, but twice, three times if I can, as many times as I get a chance to play this game. I want to inspire somebody else to play this game, accomplish their dreams. That’s another accomplishment of mine. I want to be a positive role model for the next generation. It’s all about trying to grow the game and using every opportunity I can to be a positive role model. That’s bigger than the game for me.”

He is the worthy heir to Maris and the Babe. With No. 62, he is the authentic home run king and the new standard, the one to be chased by all others who come after him.

More MLB Coverage: