MLB Is Giving Older Players More Money As the Game Gets Younger

To much fanfare, MLB teams tossed aside their actuarial tables to spend huge sums on free-agent players who will age far out of their prime. Carlos Correa, pending his $315 million for 12 years with the Mets, will become the 16th free agent this winter to sign a contract that pays through at least age 36. Teams spent $896 million on 41 player seasons age 36 or older—on average, betting $22 million per player per year into their late 30s.

To less fanfare, around these same two months, the Cubs released Jason Heyward, the Reds released Mike Moustakas and the Red Sox released Eric Hosmer with a combined $83 million left on their contracts. (The Padres owe the bulk of Hosmer’s guaranteed salary.) They were three of seven players this year with contracts of four or more years that were paid to go away rather than complete their contracts. Total money to these seven players not to play: $181 million.

Dead Money, 2022 Released Players

Owed | Original Contract ($/Years) | |

|---|---|---|

Robinson Canó, Mariners/Mets | $45M | $240M/10 |

Eric Hosmer, Padres/Red Sox | $39M | $144M/8 |

Justin Upton, Angels | $28M | $106M/8 |

Mike Moustakas, Reds | $22M | $64M/4 |

Jason Heyward, Cubs | $22M | $184M/8 |

Chris Davis, Orioles* | $21M | $161M/7 |

Elvis Andrus, Rangers/A’s | $4M | $106M/6 |

*Retired, but receives money as part of restructured contract

Part of the strategy behind the megadeals this winter is an accounting trick. By amortizing the cost of the player over more years, the club reduces its potential competitive balance tax hit. The average annual value of the contract counts toward the CBT number. Trea Turner, for instance, is a $30-million-a-year player, but the Phillies cut his AAV to $27.2 million by giving him an 11-year contract that will pay him through age 40.

Another strategic factor is the NL’s adopting the DH in 2022, which allows all teams in baseball (not just the 15 in the AL) to rationalize megadeals with the escape hatch of the DH as the player ages out of a defensive position.

Another factor: star power. The deep free-agent field included 11 players named to the All-Star team this year.

But the factor I find most fascinating is the new theory among clubs that sport science can keep a player producing at an advanced age better than in the past. Every club has boosted its investment in sport science in recent years by hiring experts in nutrition, kinesiology, recovery, sleep, biomechanics and other nonplaying areas. It is not unusual for a manager to give a day off to a healthy player strictly on the advice of the team’s sport performance coaches, based on energy expenditure and schedule. The general term for such proactive workload management is “prehabilitation.” It is designed to prevent injuries rather than respond to them.

But here’s the catch: Clubs are working with only a theory that such advances will produce a generation of players who remain productive through their late 30s. There is no evidence that is happening. In fact, the opposite is happening.

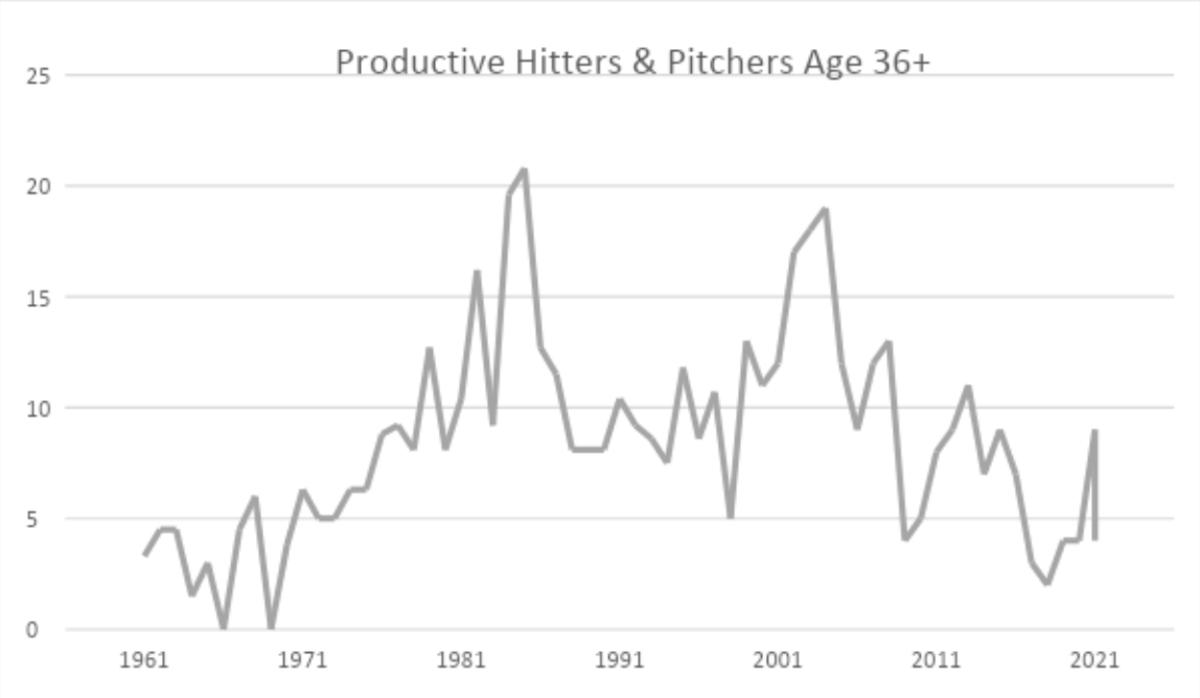

Productive players in their late 30s are the rarest they have been in 50 years. To put together a quick actuarial chart on this subject, I looked at each of the 62 seasons of the expansion era (since 1961). I started with a question: How many players 36 and older were productive in each season? I defined “productive” as satisfying two basic requirements: enough plate appearances or innings to be considered qualified and either an OPS+ or ERA+ at 100 or better. “Productive” loosely means being at least an average regular.

To account for differences in the number of teams, I prorated each season’s number of productive older players by 30 teams. For instance, seven such players among 24 teams in 1976 is equivalent to 8.8 today.

What did the numbers yield? A 62-season trendline that loosely resembles an uppercase M—and ever since baseball began testing for PEDs the game has been writing the last downstroke of the M.

Some highlights:

- Baseball was a young man’s game in the 1960s and ’70s, through three expansions. In those times many players still took offseason jobs and used spring training to “get in shape.”

- The early 1980s saw such a huge growth in extended careers that it looks like an outlier. The years ’82 to ’87 averaged 13 productive players per season, compared to 6.5 in the 11 years before and 7.9 in the 11 years after.

- The steroid era extended careers. From 1999 through 2008, which reflects the last group who accrued the benefits before testing began in ’04, the game averaged 13.6 productive older players each year—an extended peak compared to the early-’80s spike.

- In 14 years after the steroid era’s peak, the number of productive older players has been cut by more than half, to an average of 6.1 per season. Last season saw only four productive older players: Justin Turner, Carlos Santana, Justin Verlander and Adam Wainwright. In 2004 there were 19.

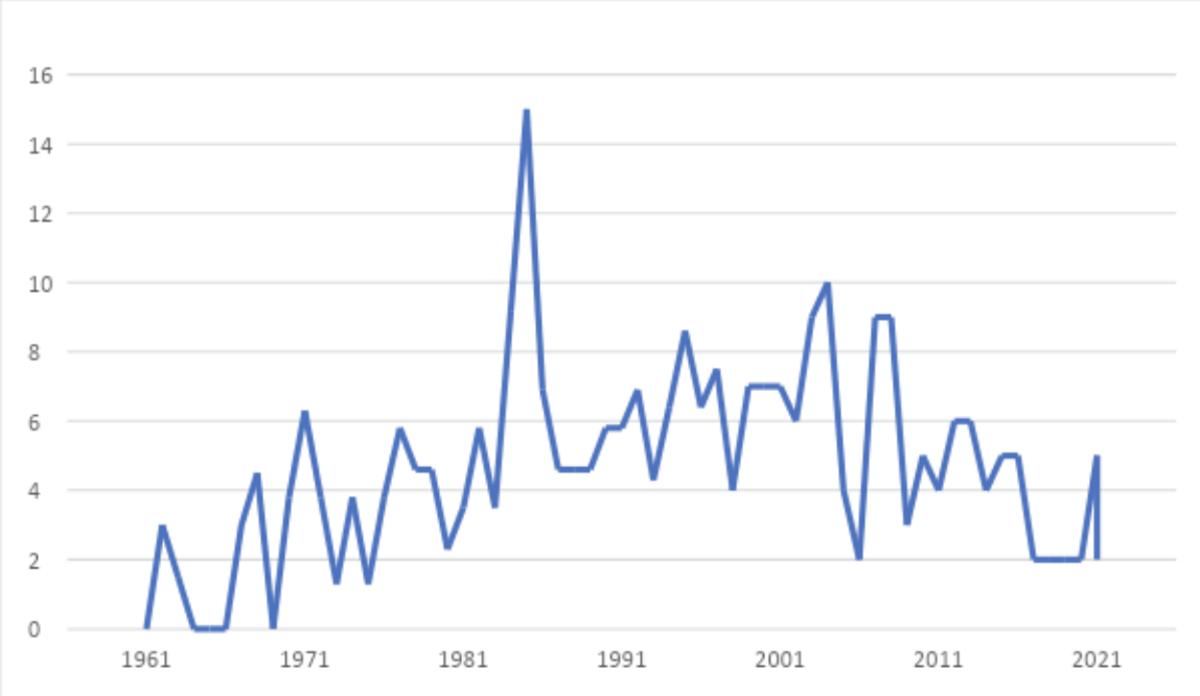

Maybe the numbers are going down because fewer pitchers overall throw enough innings to qualify. So, let’s remove pitchers and examine the aging patterns for hitters:

Again, there's been a decline since 2009, and the numbers do not support the massive investments in aging hitters. The past six seasons have seen only 15 older productive hitters, an average of just 2.5 per year—or half as many as the previous six-year average and down from seven per year in the steroid era.

Two snapshots of productive age-36-plus hitters:

- 2004 (10): Moises Alou, Jeff Bagwell, Craig Biggio, Barry Bonds, Vinny Castilla, Jeff Conine, Steve Finley, Jeff Kent, Tino Martinez, Rafael Palmeiro.

- 2022 (2): Carlos Santana, Justin Turner

Older players are getting more money as the game is getting younger. The average age of a hitter last season was 28.3. In 2004, it was 29.3, the oldest mark in baseball history (with the exception of the years 1944 and ’45, when many players served in the military).

The average age of a hitter exceeded 29 every year from 2000 to ’07, thanks largely to steroids. Except for 1944 to ’45, it never happened once before or since. It has been no higher than 28.4 for the past eight seasons—the first such extended emphasis on youth since the 1970s.

This is not to say sport science isn’t working. Remember that it benefits younger players, too. As velocity and spin rise, the game tilts more to youth.

Fast forward to 2031, when at least eight players will be 36 or older on current contracts:

2031 Salaries, Age 36+

Age | AAV | |

|---|---|---|

Aaron Judge | 39 | $40M |

Francisco Lindor | 37 | $34.1M |

Corey Seager | 37 | $32.5M |

Mookie Betts | 38 | $30.4M |

Trea Turner | 38 | $27.2M |

Carlos Correa | 36 | $26.5M |

Xander Bogaerts | 38 | $25.45M |

Bryce Harper | 38 | $25.4M |

Two more issues are worth mentioning in these investments in aging players:

1. Inflation. Albert Pujols’s $24 million AAV ranked him as the third-highest-paid player when he started his 10-year contract with the Angels. At the end of the contract, it placed him 24th. The $24 million in 2012 was the equivalent of $28.3 million in ’21.

2. Market resources. Bad contracts don’t alter the way the biggest clubs do business. After the Yankees signed free agent Jacoby Ellsbury to a seven-year, $153 million deal through age 36, Ellsbury returned one productive season (his first). He did not play at all in the final three seasons of that deal. Yet the $21.85 million in dead money each year did not deter New York: It made the postseason each of those years and finished seventh, third and first in payroll.

In 2022 and ’23, 11 contracts worth at least $100 million over five or more years will have ended. In most cases, the final year would not qualify as productive: Canó, 40; Joey Votto, 40; David Price, 36; Davis, 36; Evan Longoria, 36; Yu Darvish, 36; Charlie Blackmon, 36; J.D. Martinez, 34; Justin Upton, 34; Andrus, 33; and Heyward, 33.

The newest class of players with megacontracts includes more money at more advanced ages. Until the trendline changes, the incentive for clubs is less about sport science than it is accounting and the cost of acquiring the player.