Before Jackie Robinson, This Forgotten Man Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier

George Washington. Jackie Robinson. Neil Armstrong. Many men and women have immortalized themselves by being first—you’re first; you’re remembered.

That is, until you’re not.

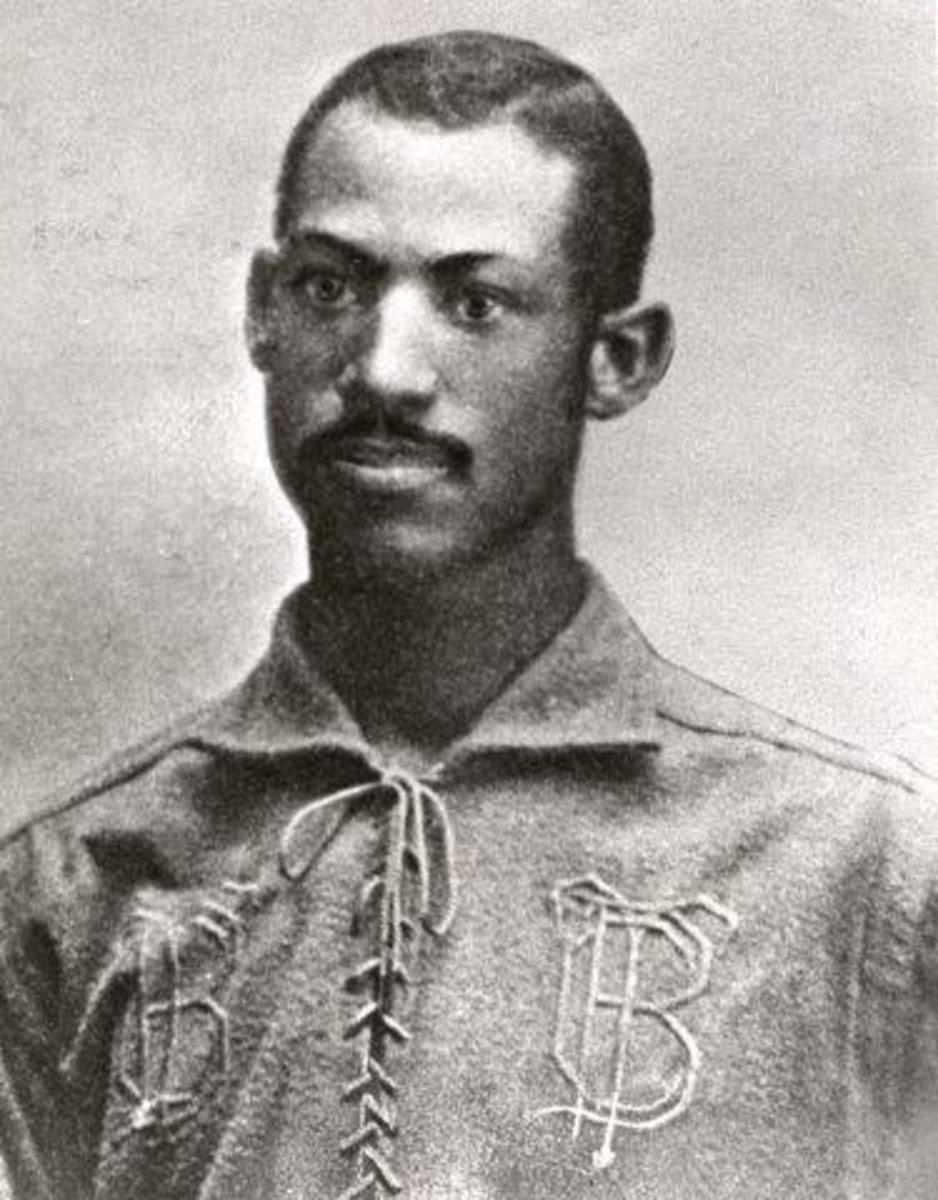

In 1884—63 years before No. 42 stepped into a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform—Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker suited up for 42 games with the Toledo Blue Stockings, a professional club in the American Association (now the American League), becoming the first Black man to play in the major leagues. But even in the city where he played, Walker is often overlooked, says John Husman, a baseball historian and member of the Society for American Baseball Research.

Why? It’s complex.

For starters, many players become forgotten because of a lack of record keeping, says SABR’s Adam Darowski, a baseball statistician and historian who chairs the organization’s 19th Century Overlooked Legends Committee. In Walker’s case specifically, Darowski says his time in the big leagues was too brief.

“I think that a lot of his contributions were lost,” Darowski says. “Jackie Robinson was a star. He was so in your face that you couldn’t ignore him, whereas Walker was there for a year, and then he disappeared from the official record.”

Husman, who’s written several articles about Walker for SABR, has his own interpretation: “I think Jackie Robinson has been the overriding factor for most people for many years. Trying to undo that or debunk it is pretty tough. It would be easier to debunk Santa Claus than debunk the Jackie Robinson story.”

In Husman’s profile of Walker, he quotes biographer David W. Zang, who said Walker “was no ordinary man, [and] no ordinary baseball player.”

Darowski says, in a time when baseball and America were deeply segregated, Black men had to work to get access to the game themselves. He says that Walker in particular was a “pioneer” who got “lost in the middle,” because he arrived on the scene before the Negro Leagues were invented.

“Moses came a little too soon, when there weren’t many Black teams being organized,” Darowski adds. “So he actually never played on an all-Black team in his life. He was always playing on integrated teams, and that was pretty rare.”

The teams that did let Walker play weren’t necessarily trying to make a statement or be pacesetters in integrating the game, though. Husman says the motivation was a lot simpler—Walker could play, and teams were willing to pay him.

“I think if you announced that that was your goal, that you were going to try and integrate the game, it would have been overwhelmingly opposed,” Husman says. “The climate then was so much different.”

After playing collegiately at both Oberlin College and the University of Michigan, Walker left school to pursue baseball professionally. He ended up signing with Toledo for the 1883 season, playing in 60 of the team’s 84 championship games and appearing in preseason and postseason contests, as well.

It was during that season that Walker first faced opposition from future Hall of Fame inductee Cap Anson in what Darowski says is one of his favorite anecdotes about Walker.

Anson, Darowski says, was “probably the greatest player of the 19th century, but also a terrible racist.” On Aug. 10, 1883, Anson’s Chicago White Stockings (now the Chicago Cubs) came to Toledo for an exhibition game. Walker, who was injured, wasn’t even scheduled to play, but his presence still caused a stir. The Chicago team, led by Anson, asserted that they wouldn’t play if a Black man was there, but Toledo Blue Stockings manager Charlie Morton called their bluff.

“Morton said, ‘Well, now that you’ve said that, he is going to play,’” Darowski recounts. “Even though he was injured, Walker was put in the lineup, and Anson threw a fit, but ultimately he relented, because he wouldn’t get his gate money if he canceled the game.”

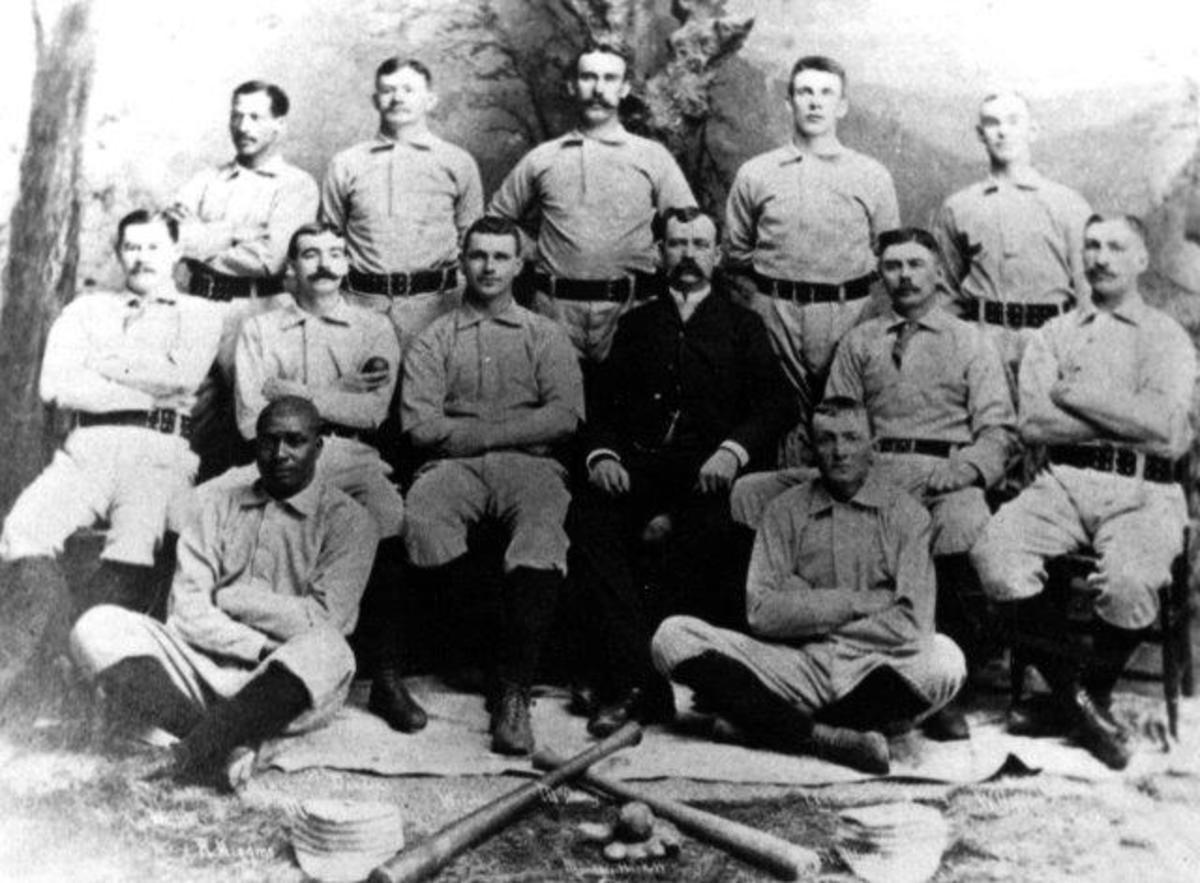

Walker and the Blue Stockings’ success during 1883 propelled the team to the American Association for the 1884 season. That promotion officially made Walker the first Black player in Major League Baseball. His younger brother, Weldy Walker, also joined the team for five games midseason, making him the second Black man to break baseball’s color barrier. (That, technically, makes Jackie Robinson the third, a fact Husman says he uses to stump people during baseball history quizzes.)

During that season, Walker, who was a catcher, faced opposition not just from other teams, but from fellow Blue Stockings players as well. Husman says a story that sticks out is Walker’s relationship with Toledo pitcher Tony Mullane.

According to Husman, Mullane said he “would not take orders from a Black man” and was resistant to following Walker’s signals.

Mullane himself recounted the tension decades later in a newspaper interview: “[Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals. One day he signaled me for a curve and I shot a fast ball at him.”

Ultimately, Walker told Mullane that he would catch without giving signals, but wouldn’t allow himself to be crossed up by Mullane. For the rest of that season, Walker caught everything without knowing what was coming, which was “pretty brutal” considering players caught barehanded during that time, Husman says.

Unfortunately, Husman adds Mullane’s attitude was not uncommon during the time Walker was active.

“There were many people who felt that way,” he says. “In fact it may have been the prevailing opinion. That was the way of life for a Black man moving in white circles.”

Ultimately, after 42 games with Toledo, Walker was released midseason due to injury. He never played in the major leagues again. He bounced around different teams, finally landing in Newark with the International League’s Little Giants. There, he formed an all-Black battery with pitcher George Stovey.

During an exhibition game on July 14, 1887, Anson reared his head again—only this time, the outcome was different.

After the 1883 incident in Toledo, Anson vowed “he would never take the field against a Black man again.”

“He made good on that. He did that,” Husman says.

Sure enough, Anson’s White Stockings didn’t have to worry about Stovey and Walker during the 1887 exhibition game. On that same day, the International League said it would not approve the contracts of any additional Black players.

Walker moved from Newark to Syracuse, also in the International League, but his play slumped. After playing in Syracuse for the 1888 and ’89 seasons, he was cut—officially ending Black participation in the International League until Robinson joined the Montreal Royals in 1946.

Husman says another reason Walker’s contributions might be overlooked is because of how his story ended in comparison to Robinson’s.

“[Walker and Robinson] fought the same fight, fought the same bigotry and suffered at the hands of people that wanted to do them harm,” he says, “but I think the result is different. Fleet Walker actually led to segregation of the game, which most people think is a negative, and Jackie Robinson’s effect on the game was opposite.”

Though Walker’s contributions have been largely overlooked, organizations like SABR are doing their part to set the record straight. Darowski says there’s “a lot of momentum around his story.” In 2022, SABR’s Overlooked 19th Century Baseball Legends Project named Walker—a first time finalist—one of their “Overlooked 19th Century Base Ball Legends.” The award honors historical baseball figures who have not yet been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Darowski says it’s important to “know what came ahead of you” and which pioneers to be thankful for.

“You need to try and be accurate,” Husman agrees. “We’re just trying to get the story right.”