MLB Is About to Become Much More Exciting

“A stalling game is a game between coaches. But the [shot] clock gives the game back to the players.”

—Jacksonville basketball coach Bob Wenzel, 1982

This is the year baseball gives the game back to the players. The bans on shifts and stationing infielders in the outfield help restore baseball as an athletic competition, not an intramural competition among analytics departments as to who can build a better algorithm.

The Shift Era is over. Good riddance. May it never come back.

It was an ugly era and even more deleterious to your enjoyment of the game than you realized. The biggest cost of The Shift Era: it destroyed left-handed hitting.

The shift turned traditional baseball upside down. By design and by human nature, baseball always was a game that favored left-handed hitting. Because players run the bases counterclockwise, left-handed hitters begin closer to first base than righthanders. Because most pitches are thrown by righthanders (73% last year), lefties get the platoon advantage far more often.

But then shifts came along. The adoption was slow at first—only 12% of pitches in 2017. Then shifts more than doubled in just two years, to 26%. And then it became mainstream as teams invested more resources in analytics and saw how much it depressed offense. Over the past three years the shift rate was 32%—but most importantly, 52% to lefties.

In that time of rapid growth, teams learned how to pitch into the shift. For instance, from 2017 to ’22 cutters from right-handed pitchers to left-handed hitters—pitches boring on a hitter’s hands and almost impossible to carve away to the opposite field—jumped 49%!

Lefties were put at a major disadvantage—not by their own making, but by the making of front offices and by MLB, which allowed the entertainment-killing scheme to continue. Shifts rendered left-handed hitting the worst it’s been in at least a generation.

(Shifts work better against lefties than righties because with a shorter throw to the pull side infielders can play deeper, covering more ground.)

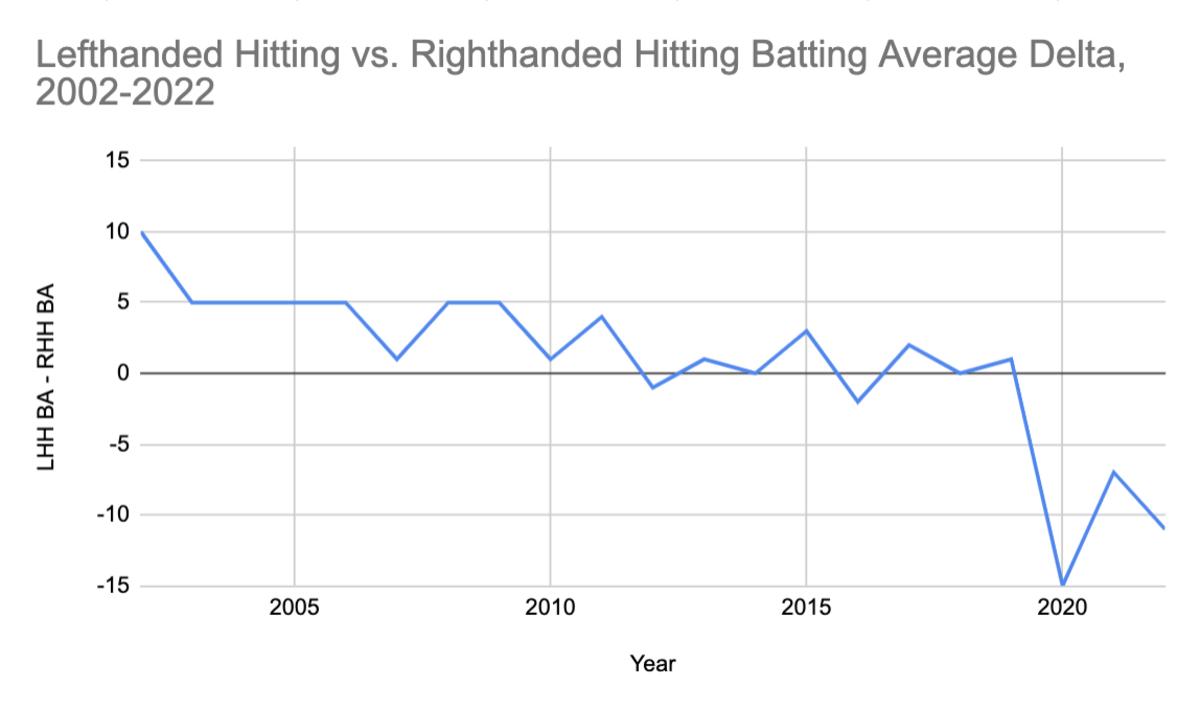

This line graph tells you how fast and by how much shifts changed the game. It tracks the difference in batting averages of left-handed hitters vs. right-handed hitters since 2002. The delta shows the age-old edge for lefties—until ’20, when baseball truly became an unfair game for lefties.

If there is an argument in favor of shifts it is that they are intellectual capital that should be protected, not regulated. If my team builds a better mousetrap than your team, why should we be punished by regulations that even the playing field?

Such an argument works fine in capitalism, but it is garbage when it comes to why big-time sports exist: entertainment. Nobody bought a ticket to watch analytics departments crunch numbers. Every sport must balance innovation—or in today’s parlance, the hacking of the sport—against entertainment. A thumb must always be placed on the entertainment side of the scale.

Fifty years ago, on a Friday night in December, Temple played at Tennessee in the championship game of a season-opening basketball tournament, the Volunteer Classic. Tennessee had run DePaul off the court, 96–61, in the semis. Temple coach Don Casey wasn’t going to let that happen. With no shot clock then, he decided his Owls would milk the clock with each possession.

Tennessee coach Ray Mears had his own play. He decided to stick to a zone defense rather than play man-to-man against the quicker Temple team. What happened that night was that two coaches staged the most boring college basketball game ever played.

The score at halftime was 7–5, Tennessee. The second half did not include a single field goal. Temple held the ball—with two guards passing the ball back and forth while the Vols stuck to their zone—for 32:05 of the 40 minutes. Tennessee won, 11–6.

The fans pelted the floor with ice. Tennessee was so embarrassed that the school president asked Mears to bring the team back to the floor to play an intrasquad scrimmage.

Scoring declined every year for the next decade in men’s college basketball. Coaches ruled the game with zone defenses and stall tactics, taking the game away from the players and fans. Dean Smith of North Carolina was considered a genius for his four-corners offense. He once said he used the clock-killing, sleep-inducing tactic 107 times to protect a lead between 1966 and ’72. His record with that tactic: 105–2.

Intellectual capital? Baloney. The Sun Belt conference, which saw a 22–20 championship game snoozer in 1978, understood. It adopted a shot clock in ’81. Four years later, the NCAA introduced a 45-second clock, which became a 35-second clock in ’93. The game thrived. Players decided games, not coaches.

Baseball finally is having its shot-clock moment, an awareness that the most entertaining form of sport is when the game belongs to those who play it. The shift altered careers. Players such as Brandon Belt, Brian McCann, Jay Bruce, Kole Calhoun, Alex Gordon, Ryan Howard, David Ortiz, Carlos Santana, Kyle Schwarber and Joey Votto have statistics less than what they would have been in a traditional game—and yes, Shohei Ohtani, too.

Ohtani made 64 outs on balls hit at least 100 mph against the shift last year. Only Corey Seager and Yordan Alvarez suffered more often on such extremely hard-hit balls when facing the shift. Overall last year there were 4,080 100-mph rocket outs against the shift, about four times as many as in 2015 (1,067). Ohtani, Seager, Alvarez ... these are stars of the game being held down by “intellectual capital.”

Seager is the most extreme example of how the shift changed the game and careers. In 2016, when he saw just 11% shifts, Seager hit .333 on balls in play to the pull side. Last year, he hit .239 on those same balls while facing 93% shifts.

Seager lost at least eight hits just on balls that were hit 100 mph or more, usually with the second baseman playing in short right field. Watching a second baseman catch a line drive 210 feet from home plate is the equivalent of watching a college basketball team run the four corners. It’s a bad look for everyone except the genius who concocted how to take fun and athleticism out of athletics.

This year baseball will look better. The traditional spacing of infielders will return, inviting athleticism and effort, rather than the clusters of large appliance-sized fielders planted where a laminated card cooked up by math wizards tells them to stand. You will see more diving attempts and more well-struck balls being the hits they always have been, which means more rallies and more baserunning.

Watch MLB games live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

The shift turned baseball into what college basketball was before the shot clock: a more boring game dictated by people not competing on the field. After the Sun Belt adopted the shot clock, then-South Alabama coach Cliff Ellis explained why the game had to be taken out of coaches’ hands.

“When a family spends $40 on tickets, food and beverages, a 22–20 game won’t make them happy,” he said. “We’re in the entertainment business, and that’s not entertainment.”

This year you will enjoy baseball like you have not for years (and that’s not even considering baseball’s hallelujah innovation, the pitch timer). But nobody will enjoy it more than left-handed hitters. Here is how badly The Shift Era destroyed left-handed hitting:

- Since the mound was lowered in 1969, there had never been a season with as few as 10 left-handed hitters with 150 hits. Then it happened in 2021. And again in ’22. That was half as many as there were in ’17 (20) and less than a quarter as in ’98 (43).

- Left-handed hitters’ on-base percentage (.309), batting average (.236) and wOBA (.306) last season were the worst in at least 21 years.

- Yankees left-handed hitters last year set the template to how the shift skewed the traditional reward system: Don’t try to hit through it; try to hit over it. They hit just .214 while leading the majors in fly-ball percentage and pull percentage and finishing last in ground-ball percentage. Nearly one quarter of their hits from lefthanders were home runs (24%).

- The big-picture proof of the skewed reward system: left-handed hitters last year had 4,088 fewer hits than they did in 2009, a decline of 21%. They lost 29 points off their batting average (.265 to .236) and 22 points when they put the ball in play (.305 to .283). But they did hit home runs at a higher rate.

- Blue Jays left-handed hitters hit just 20 home runs and had 202 hits. Both totals were fewer than Charlie Blackmon had by himself in 2017. They have since added Daulton Varsho, Kevin Kiermaier and Brandon Belt, all lefties.

- Twenty-five free agents signed contracts of three years or more this winter. Only two were left-handed hitters with big-league experience: Brandon Nimmo (8 years, $162 million) and Andrew Benintendi (5 years, $75 million), neither of whom has ever hit more than 20 homers or driven in more than 90 runs. A third lefty batter, Masataka Yoshida, signed with the Red Sox for five years and $90 million after playing seven professional seasons in Japan.

To worsen matters, while the shift took away hits from left-handed hitters, the flow of lefties into the big leagues declined. There are fewer left-handed hitters in MLB than at any time in the past two decades. From 2013 to ’22, at bats by lefties dropped 12%. They accounted for 44% of at bats a decade ago but only 39% last year.

Ah, but now there is hope. Twelve of the top 29 draft picks last year were left-handed hitters, plus two switch-hitters. The baseball world that Jackson Holliday, Termarr Johnson and the other lefties of their generation will inherit is set up to be a fairer and more entertaining one.