Tim McCarver Was Baseball’s Renaissance Man Who Was ‘on a Perpetual Picnic’

In the summer of 1959, a writer from Memphis, David Bloom, visited Rochester, N.Y., and the Triple-A Red Wings to check in on 17-year-old catcher Tim McCarver, who had graduated only two months earlier from Memphis’s Christian Brothers Academy.

“As for McCarver, he’s on a perpetual picnic,” Bloom wrote. “Happiest guy around, full of fun, in the midst of everything the Red Wings do.”

The picnic never ended, at least not until he took his last breath. Tim McCarver died Thursday in his beloved Memphis at the age of 81. A man of immense interests, McCarver enjoyed them with gusto. He wrote five books, read poetry, studied and enjoyed fine wine, recorded an album of American standards, hosted a TV sports interview show, won three sports Emmys, appeared in movies and visited art museums wherever his travels took him.

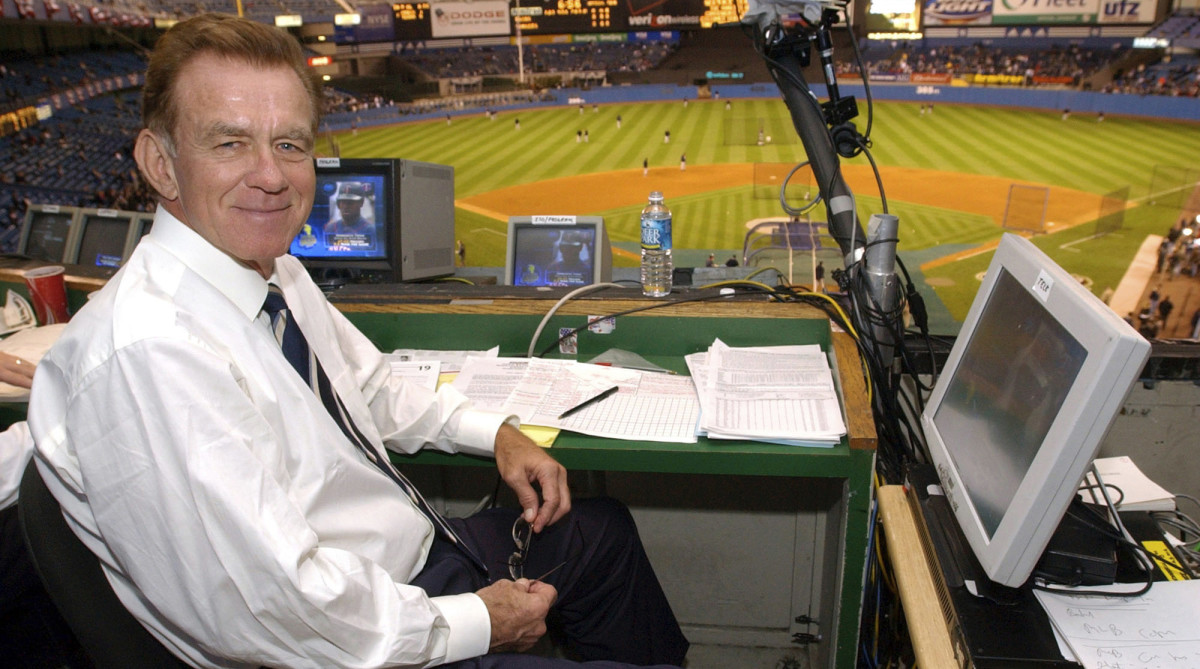

His impact on baseball was astoundingly deep and prolific. McCarver played major league baseball 21 years across four decades, beginning with that summer of ’59 when he debuted at 17. He became a broadcasting legend for his work with several ballclubs but especially on national broadcasts when he became the definitive baseball television analyst. Watching and studying the game he so deeply loved, McCarver radiated joy. Being around Tim at a ballpark, and even knowing his varied interests, you knew two things were true: 1) you were going to learn something about baseball, and 2) there was no other place he’d rather be.

“He was the best audience I’ve ever had,” says Joe Buck, his Fox partner from 1996 to 2013. “His laugh lit up a room and was all encompassing. He actually knee-slapped. The only person I have ever met who did that.”

Until McCarver came along, no one had ever done more than 10 World Series as an analyst, due partly to a rotation of networks covering the series, the star power of play-by-play callers and guest “name” analysts. McCarver elevated the position by merit. He covered 24 World Series across three networks (ABC, CBS and Fox) and with four play-by-play broadcasters (Al Michaels, Jack Buck, Sean McDonough and Joe Buck).

His Memphis drawl, interest in humanities, cornball humor (“That was a Linda Ronstadt fastball: blew-by-you”) and critical eye—his father was a Memphis police lieutenant and his pitching mentors and good friends were the uncompromising Bob Gibson and Steve Carlton—made him the quintessential baseball analyst. He didn’t talk too much. He let the game breathe, interjecting only when he had something salient to say, which is the essence of making one’s words even more impactful.

The adroitness of McCarver was never more evident than in the bottom of the ninth in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, right after Luis Gonzalez of the Diamondbacks fouled back a first-pitch cutter from Mariano Rivera of the Yankees. McCarver saw how Yankees manager Joe Torre, opting to be more aggressive than passive, played the infield in with the bases loaded and one out and the score tied.

“The one problem is Rivera throws inside to lefthanders,” McCarver said. “And lefthanders get a lot of broken bat hits into shallow outfield. The shallow part of the outfield. That’s the danger of bringing the infield in with a guy like Rivera on the mound.”

He made his point. He did not belabor it.

On the very next pitch, Gonzalez hit a broken-bat single into the shallow part of the outfield.

Buck: “Floater ... Center field ... The Diamondbacks are world champions!”

And then the two of them said nothing for the next three minutes, 31 seconds.

The versatile McCarver could be jocular or bitingly critical. The Mets fired him in 1999 essentially because players and management believed he was too critical. McCarver, for instance, routinely would point out how Darryl Strawberry never bothered to change his positioning much in right field. “The Strawberry patch,” he called the worn sod in right field where Strawberry stood.

“He also had his core beliefs about the game and about the right way to play,” Buck says, “and he was never afraid to share them, and he was never afraid to criticize if somebody’s play didn’t fit in those parameters. And he was always the first one in the clubhouse the next day ready to let a manager or a player have their say. So, he would criticize but he would also face the person that he criticized the night or the day before.”

As with players and musicians, you can tell a lot about a broadcaster by work habits. What does a person do when no one is watching—when it is not showtime? Springsteen, for instance, does run-throughs with the same intensity as a concert. I always knew what game Fox was broadcasting on a Saturday afternoon when I saw Timmy Mac in both teams’ clubhouses on the Friday night before the game. He wanted to talk to the starting pitchers or, of course, the catchers to better prepare for the broadcast. He played 21 major league seasons and never stopped learning. He was the smartest of baseball analysts: smart enough to know what he didn’t know. Following him into that World Series analyst chair, along with Harold Reynolds, forever will be one of my most humbling and proudest honors.

In that summer of ’59, when the perpetual picnic began, Tim McCarver was considered the finest athlete to come out of Memphis in half a century. A star also in basketball and football, he conditionally accepted a football scholarship from Tennessee. Six major league scouts attended his high school graduation. A few days later, he signed a “bonus baby” contract with the Cardinals for $75,000, an enormous amount in those pre-draft days. Three months later, still only 17, he was batting leadoff for the Cardinals, the first catcher to hit leadoff at least four times in a season in 20 years. When the season ended, he enrolled in classes at Christian Brothers College, wearing the derby hat all freshmen were required to wear at the time.

That’s an image that never faded: a big league player taking college classes in a derby. It fit McCarver. He was more than a ballplayer and the finest baseball analyst. He was a renaissance man in the true sense of the word. Renaissance comes from the Italian phrase la rinacita, meaning a rebirth, in the original form referring to a rediscovery of Greek and Roman antiquity, especially in the arts and humanism. McCarver kept learning. Kept striving. He followed his heart, and while at the top of his game at a time when platforms and social media began to hand out bullhorns to the unhappy, he stayed the course.

“Best teammate I ever had,” Buck says. “He was a fierce defender of people who were in his circle. He taught me to deal with criticism at a young age. It was two words. The second was ’em.”