Mariners’ Jarred Kelenic Is Primed for a Turnaround in 2023

The Mariners recently invited their players to a bat-fitting session. They hired a private company to run players through motion-capture technology to find what size, shape and weight of bats best fit their swing movements. The star of the show was the second-worst hitter ever with at least 550 plate appearances.

Mariners outfielder Jarred Kelenic is a career .168 hitter. Only John Vukovich (.161) was worse with that many times at bat in the big leagues. Vukovich was a journeyman utility infielder who played 277 games over 10 seasons. Kelenic is 23 years old and only two years ago was ranked ahead of Julio Rodríguez as the fourth-best prospect in baseball. Mariners hitting coach Jarret DeHart said the motion-capture results graded Kelenic’s swing “off the charts” in terms of efficiency.

“Kelenic made some significant swing adjustments,” DeHart says. “As we did our bat fitting, we were checking on some of the adjustments we made with him last season and some things we were hoping to address with him. He addressed everything we asked of him, just in terms of his body working more efficiently.”

The AL West is a deep, fascinating division. Only Oakland is not a legit playoff contender. How it plays out may come down to one difference maker who realizes a huge upside. Last year it was Justin Verlander of Houston, the first pitcher to win the Cy Young Award after not throwing a pitch the previous season. This season it could be Kelenic, a career .168 hitter, who could become a star, or at least a key contributor.

Before I explain Kelenic’s potential turnaround, I give you the biggest swing players on each team in the AL West, ranked by their singular impact—for better or worse—on how the division plays:

Biggest Swing Players, AL West

1. Jacob deGrom, Rangers

He has the best pure stuff of anybody in baseball, but because of the pandemic and injuries has made only 38 starts over the past three years. Day 1 of his five-year contract with Texas began with tightness in his left side that kept him off the field on a cool day. A big deal? No. By itself, very minor. But this comes after six weeks of throwing and questions at age 34 about his durability because of how fast his body moves through his delivery.

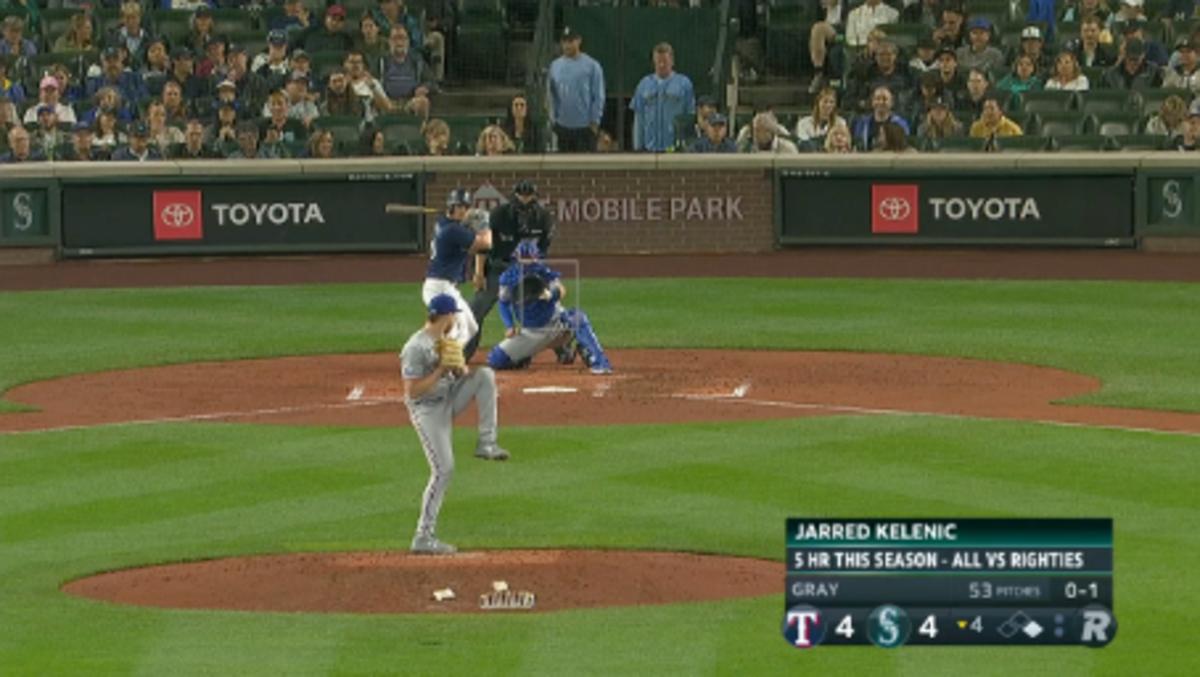

2. Kelenic, Mariners

Seattle won 90 games last season with a below-average offense (18th in scoring) and little help from the left side. He is their X factor.

3. Anthony Rendon, Angels

He has played only 102 games over the past two years because of injuries and been a below-average hitter (97 OPS+). At 33, time is working against him. Only two qualified third basemen that old have posted better than a 100 OPS+ over the past three seasons: Eduardo Escobar and Justin Turner.

4. Jose Abreu, Astros

One of the best free-agent fits, Abreu at 36 has lost nothing off his productive bat (93rd percentile last year in average exit velocity and at 92.2 mph the second hardest of his career). First base was one of the rare spots where Houston needed an upgrade. Its first basemen ranked 25th last year in OPS and 28th in RBIs.

5. Seth Brown, A’s

He has the talent to be an All-Star. Brown was one of only a dozen players last year with 25 homers, 25 doubles and 10 stolen bases. I’ve always loved his swing—he destroys fastballs—and the ban on shifts should lift him well above his career .229 batting average. He does have one glaring weakness: Brown is a career .275 hitter/.552 slugger against fastballs but only .184/.359 against non-fastballs.

Kelenic still has an enormous ceiling. He was one of the top prospects in baseball who posted a career .909 OPS in the minors, has size (6'1", 206 pounds), decent speed, power from the left side and a strong throwing arm. The tools are there. But they have not translated to major league success.

He was late on velocity. Kelenic last year hit .130 on pitches 95 mph or faster.

He didn’t make good swing decisions vs. spin. This is the biggest separator between hitting in the minors and majors today. Kelenic is a career .128 hitter against breaking balls. Most alarmingly, with two strikes he chases breaking pitches out of the zone 44% of the time. He hits .034 when he does that.

He was not on time when he got his pitch. This is telling. Even the worst hitters should exploit count leverage. Kelenic hit .150 on first pitches last season. He swung six times at 3-and-0 fastballs and whiffed three times and fouled off two.

Sounds ominous, right? It’s not as bad as it seems. Kelenic hasn’t lost the tools that made him a top prospect. He is healthy and still very young. What he needs to do is get out of his own way. Stop being so mechanical at the plate. Stop chasing results and trust a simplified process. Perhaps the lowered expectations will allow a breakout to happen.

“Physically, you probably wouldn’t notice too much that’s different,” DeHart says. “It’s really exciting because he’s going to have a mental fresh start. He’s coming in with a more relaxed mindset.

“The [swing] changes are a little more subtle. It’s similar to what he did last year in terms of setup. But the biggest thing is his cleaning up some things in his bat path. He’s taking out some inefficiencies and useless movements. Posturally, he’s a little taller with a little more adjustability that creates more balance. The bat path is a lot different from last year. It’s much, much better.”

Let me show you what it means to struggle as a young player with high expectations and how it can create a downward spiral. Let’s first focus solely on Kelenic’s setup—using the moment when the pitcher is at the top of the leg kick.

April 10

Fairly balanced. The bat is off his shoulder. What you don’t see is that Kelenic uses a slight waggle with the bat while waiting. That can be a trigger mechanism or an indicator of tension.

April 28

Only 18 games into the season, hitting .148, Kelenic changes his setup. He opens his stance, puts more weight on his back leg and holds the bat nearly straight vertical. He bounces the bat off his back shoulder before reloading.

July 31

The Johnny Damon phase (without the same results). After two months in the minors, he comes back with another new setup: even more open, with more bend in his legs and a pumping mechanism with the bat. It did not work. After going 2-for-27 over 10 games, he is sent back to the minors.

September 29

Now he found something. Quieter. More balanced. Weight evenly distributed. Simpler. The extraneous movements are reduced or eliminated. He sets the bat on the shoulder—no waggle or pump—before moving it up only when the pitcher “shows him his front hip,” which is about at the top of the pitcher’s leg lift.

The effect of these changes is to be more on time with less movement and a better (less uphill) bat path.

Now we can compare what happens after the setup: two swings on similar fastballs, one in April and one in September.

Load

April

September

There is excess rotation in April. The bat is wrapped behind his head with the back shoulder raised, creating a longer, steeper bat path. In September he is more connected in a hitting position nearly identical to that of Max Muncy, one of the best fastball hitters in baseball.

In Hitting Zone

April

September

What is being “on time”? Yes, it’s about getting the barrel to the spot in the hitting zone to square up the pitch. But it’s also about sequencing the kinetic chain to get there. In April, he has yet to turn into the ball when it’s in the zone. Look at his front foot. It’s closed off, which means his front hip cannot open in time. (Brandon Nimmo had a similar problem as a rookie.) In September, the foot and hip are opening, and the bat is coming through in a connected manner. There is more freedom in his movements. His head is better at staying over his center of gravity (core).

The swing from April is a whiff. He was late getting the barrel to the ball. The barrel works too far from underneath the baseball.

The swing from September was an opposite-field home run.

His September slash line of .180/.294/.420 doesn’t look like much, but it was his best month of the season. Instead of heading home to Wisconsin, as he normally did, Kelenic spent the winter working with private coaches in California and Arizona to build on his September changes.

Does this mean Kelenic will suddenly become an All-Star? Not likely. But here are reasons to believe in Kelenic as a key contributor.

1. With Taylor Trammell out with a broken hand, Kelenic has a clear runway toward playing time in leftfield.

2. With A.J. Pollock on board to do his usual mashing against lefties, Kelenic won’t be overexposed against lefthanders.

3. Like many left-handed hitters, Kelenic will benefit from the ban on shifts. Last year Kelenic had one groundball hit to right field—one! His launch angle was 18 degrees, which is too high. Being rewarded for hard-hit grounders and line drives combined with the improved bat path DeHart raved about should bring that down.

4. The more balanced setup from last September and better bat path look sustainable. He must trust the approach and not abandon it for something else 18 games into the season if he starts slow.

By the way, Rodríguez was hitting .188 after his first 18 games last year and never panicked. But Rodríguez has extraordinary trust in himself for such a young player and is not result-oriented. More typically for someone trying to establish himself in the big leagues, Kelenic grinds hard at the mechanical side of hitting and is more prone to frustration.

5. There is pop in that bat. Kelenic swung and missed far too often last year. The good news is that when he made contact he barrelled it up 13.6% of the time, which would have tied him with Matt Olson for 13th best in baseball if he had enough plate appearances.

6. Turnarounds at 23 are not so uncommon. Matt Williams (.611, 16 HR through 136 games), Jonathan Schoop (.605, 17, 142) and Lloyd Moseby (.640, 14, 214) struggled at this age like Kelenic (.589, 21, 147).

As bad as Kelenic has been, he still hit those 21 homers in his first 147 MLB games through his age-22 season. Only 15 other hitters in the wild-card era have had that kind of pop that young. It’s not nothing.

Kelenic doesn’t have to be a star just yet. Mariners left fielders hit .212 last year with 190 total bases, ranking 27th and 28th in MLB. A solid platoon of Pollock and Kelenic could upgrade that position significantly and make a difference in the AL West.