The Great MLB Jersey Caper

Giants home clubhouse manager Brad Grems has a system for everything. Before each game, he repaints the batting helmets, erasing the dings they picked up the night before. He insists that his staff yank the zippers on all equipment bags to the middle. He spaces the hangers in each locker a finger-width apart.

Grems can identify at a glance whether someone has touched something he laid out. So when one of his assistants began pulling dirty uniforms from bags shortly before midnight on Sept. 2, 2020, after returning from a series against the Rockies, Grems could tell immediately that something was wrong. First, the zippers were askew. Then they got inside the bag.

Normally, his staffers fold pants inside of jerseys before dropping the whole bundle into a hamper. “So when there’s only pants in there and there’s not the jersey,” says Grems, “you’re like: ‘O.K., what happened?’ ”

Grems would spend the next six weeks trying to answer that question. What first seemed like an accident—two jerseys could go missing any number of ways—would grow into an investigation that entangled five teams and two police departments.

Equipment had disappeared before, but never under circumstances quite like this. It had not been six months since the pandemic paused American life. People were still disinfecting their groceries and loading up on toilet paper. Major League Baseball, in deciding to stage a 60-game season, had created a tightly guarded, sterile environment. Support staffers had been tasked with rearranging locker rooms to create social distance between players; distributing masks and policing their use; and cleaning and disinfecting everything, everywhere, all the time. The Giants’ clubhouse staff had gone so far as to install clap-on lights so that no one ever had to touch a switch.

Years earlier, when a newspaper employee posing as a journalist stole Tom Brady’s jerseys at Super Bowl LI, the NFL had to comb through the 20,000 credentials it had issued for the game to search for leads. But in 2020, MLB had limited the number of people allowed into a clubhouse to 125 per team, including the 60-man roster. So there were no journalists or other guests to suspect. Baseball had somehow stumbled into a locked-room mystery, more Agatha Christie than Christy Mathewson, more Sherlock Holmes than Homer Bailey. At the root of teams’ concern was not a few $250 shirts; it was that—as interviews, witness testimony and police reports depict—not only had MLB’s carefully constructed COVID-19 bubble been pierced, but so had the integrity of a baseball team’s most sacred space.

There seemed to be a fox in the clubhouse. Who could have possibly taken the jerseys? And how?

First Grems considered the innocent possibilities. Maybe these two away jerseys—one bearing righty Johnny Cueto’s No. 47, another with DH Pablo Sandoval’s No. 48—had ended up in another bag. Possibly they’d been left behind entirely and were twisted up in the washing machine at Coors Field. Grems knew they had made it to Denver; he had personally verified that Sandoval possessed both jerseys a day earlier, because the infielder was changing sizes. Perhaps Cueto and Sandoval had each grabbed a jersey to trade with another player, or to give away, and had forgotten to inform Grems’s team.

But when the jerseys did not turn up over the next two days in San Francisco, and after Alan Bossart, the Rockies’ visiting clubhouse manager, couldn’t find them, and with Cueto and Sandoval clueless about what had happened, Grems began to grow suspicious.

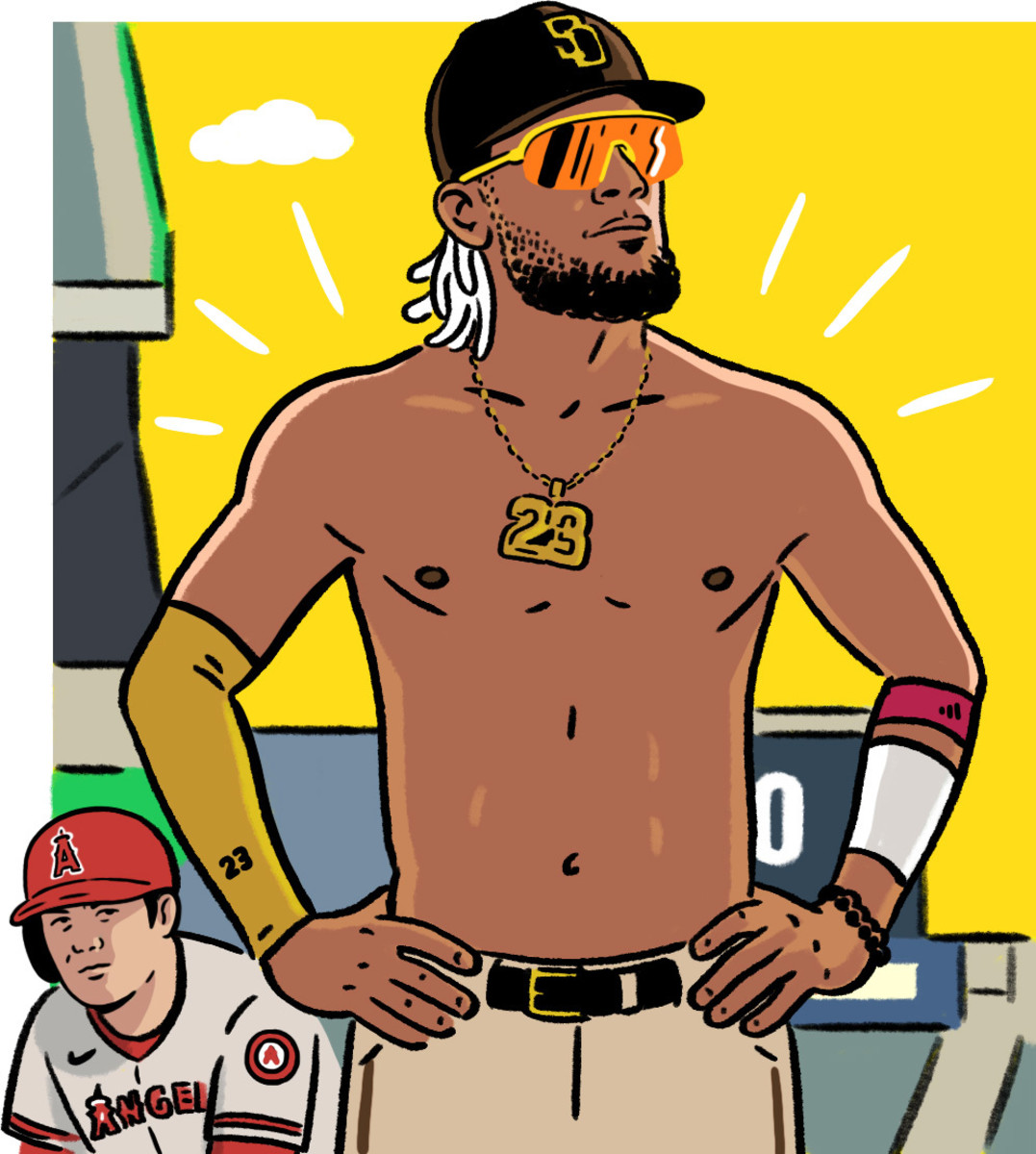

Meanwhile, San Diego’s equipment manager, Spencer Dallin, was putting out a small fire. The Padres were in Anaheim, five games into a nine-game road trip that had begun in Denver. They had worn only their pinstriped road jerseys so far, so Dallin hadn’t noticed that shortstop Fernando Tatis Jr. was missing his brown road No. 23. With the Padres slated to wear those brown uniforms Sept. 3, now Tatis had a problem. Soon, Dallin would realize that Tatis was also missing a home jersey, which he’d brought along to trade with another player. Just as Dallin made this discovery, Grems called to ask whether the Padres had lost anything in Denver.

Grems’s next call was to the Rockies’ clubhouse manager, Mike Pontarelli.

“Hey, I don’t want to accuse you guys; we’ve known each other a long time,” Grems said. “But I think you might have a problem.”

Pontarelli, in turn, called his boss, assistant general manager Zack Rosenthal, and met with Bossart, the visiting clubhouse manager, who said he would go through the security video with Kevin Kahn, the team’s vice president of ballpark operations.

To social distance, the Rockies had split visiting players between the main visiting clubhouse and an auxiliary clubhouse, across the hall; and since the whole area was restricted to essential personnel, the team had left those doors open, meaning that hallway security cameras captured activity between the two clubhouses, in addition to the main entrances.

Pontarelli is in charge of overseeing visiting players’ uniforms, so the Rockies figured the jerseys must have been stolen while he was away from the facility. (No one ever suspected Pontarelli, who started with the team as a 9-year-old batboy.) As it turned out, this was a very small window: The Rockies and the Giants had played a night game Sept. 1 and a day game Sept. 2. Pontarelli left the facility at 1 a.m. after the first game and returned five hours later. On Sept. 8, club officials huddled over a monitor, scanning footage from that period. They watched as, at 4:06 a.m., a female custodian entered the clubhouse wearing a backpack.

Finally, they had a lead. On Sept. 9, Rockies senior director of security Tony Lopez met with Brian Crandell, the facilities GM for Aramark, which manages the cleaning crews. They reviewed the footage together and agreed that Crandell would speak to the custodian in question. Three days later, when she returned for her next shift, Crandell interviewed her. She denied taking anything. Crandell believed her. The trail was cold once again.

If it wasn’t someone coming into the clubhouse, what about someone who was already there?

The 2020 season created challenges for every team, but the Rockies were unique in how they handled them. Led by owner Dick Monfort, they were one of the few clubs that avoided laying off, furloughing or cutting pay for full-time employees. Instead, Colorado furloughed its part-time employees and required most full-time staffers to take on a second job, filling in, for example, at the team store or on the grounds crew. Or in the clubhouse.

The job of a clubhouse attendant is a delicate one, and for that reason the Rockies doubled up their analytics and player-development staff here, figuring they would fit in better than, say, a 23-year-old ticket salesperson. But the transplants struggled at times to adapt. They often worked 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. from home at their regular job, then drove to Coors Field to toil until 1 or 2 a.m., performing a job in which they had almost no experience.

Technically, clubhouse attendants are employed by their respective teams—laundering uniforms and shining shoes and the like—but practically they work for the players, doing just about anything they ask. Players tip clubbies; and if their team makes the playoffs, those players can vote to award shares—or partial shares—of the resulting extra revenue to the clubbies, as well. Which can be life-changing money. (In 2022, a full player share for the World Series–winning Astros was $516,347.)

Baseball players spend more time in the clubhouse during the season than they do in their own homes. They trust clubbies almost completely. Both parties speak often of the “code.” (The clubhouse is “a sanctuary,” says Rockies manager Bud Black. “I hang jeans up with a couple hundred bucks in there ... because I trust people.”) So, it would be nearly unthinkable for a professional clubhouse attendant to swipe a few jerseys. But what about someone who was thrust suddenly into that role?

On Sept. 16, Grems’s phone pinged. It was Gavin Werner, the Giants’ director of authentications, whose job included certifying game-used memorabilia. He wanted to know whether Grems had given out any jerseys.

No, Grems texted back.

Werner replied with a screenshot of an eBay listing for Sandoval’s and Cueto’s jerseys. The listing mentioned that the items had been acquired when the team was in Colorado.

Oh s---, Grems thought. He called Pontarelli, with the Rockies.

A few days later, the Giants found a listing, posted by a different eBay seller, for the missing Tatis gear: two jerseys plus batting gloves available for $15,000. The Padres had also found the Tatis listing, and a furloughed Padres memorabilia authenticator named Russell Wuerffel confirmed the items’ legitimacy. (Pinstriped jerseys are a bit like fingerprints: Because they are handmade, each one is slightly different, and thus identifiable by where the stripes intersect the letters and the seams. For Tatis’s solid brown road jersey, Wuerffel compared photos from the eBay listing to photos from games; the loose threads on the E and the O in

san diego matched.)

Meanwhile, the Dodgers landed at Denver International Airport for a weekend series.

Game 2 between the Rockies and Dodgers was Sept. 18. Grems’s heart nearly stopped that evening when he saw that the eBay account that had been selling Sandoval’s and Cueto’s jerseys was now listing a pair of batting gloves belonging to Dodgers right fielder Mookie Betts. All Grems could think was: Did they get Clayton Kershaw’s fielding glove?

The theft of a uniform is an inconvenience, but not a catastrophe. Most equipment managers travel with spares; in a pinch, they could cobble something together to get the team on the field.

Some items, though, are irreplaceable, such as a player’s fielding glove. And one glove was widely considered to be the most so: the black Wilson 2000A-CK22 belonging to Kershaw, L.A.’s ace and future Hall of Famer, who had used the mitt in every game since his second season in the majors.

Grems immediately called Dodgers equipment manager Alex Torres, who with his staff took a quick inventory of their equipment. Kershaw’s glove was safely ensconced in his locker—but they still had a problem. They were short one gray jersey each for Betts and Cody Bellinger, the two former MVPs on their roster, as well as one for pitcher Joe Kelly. According to a statement Torres gave police, he alerted the Rockies’ Bossart, who he described as “visibly disturbed,” and Bossart notified stadium security. Bossart assured Torres that his team would take security measures overnight, and indeed the Rockies placed a chain and lock on the back door of the visitors’ clubhouse. They also stationed a guard at the front door to take the name of anyone who entered and search anyone who left. Again, video footage showed nothing suspicious.

And this, Pontarelli says, was the hardest part: having to look closely at his own guys. He was confident they hadn’t done anything wrong. But he had to investigate as if maybe they had.

“We pride ourselves on high character,” says Pontarelli. “I’m born and raised in Colorado. To have something like that happen in my hometown—you take that personally.”

Pontarelli, says Black, is “like the governor” of the Rockies’ clubhouse. “He felt bad. I go: ‘Tiny’ ”—as he’s called—“ ‘it’s O.K. We’ll find this guy.’ ”

Still, the next day, the Dodgers’ staff took another quick inventory and found that they were also missing a blue Kershaw No. 22 jersey, a blue Bellinger No. 35 jersey and a blue Betts No. 50 jersey. Torres told Bossart this was unacceptable; again Bossart called security, according to the police report. Before the Dodgers’ clubhouse staff packed up to fly home following the series, they took a more complete visual inventory of uniforms. Everything was accounted for.

By the time they got back to Dodger Stadium on Sept. 20, though, they were missing four more jerseys: two gray Kershaw jerseys, a gray Bellinger jersey and a gray Betts jersey.

By now the Denver Police Department was involved. Detective Randy Hinricher was compiling statements and getting a crash course in authenticating memorabilia. Rockies clubhouse staffers shared detailed timelines of their activities during the Dodgers series, down to the time that one person forgot his wallet and had to run back into the clubhouse.

Security footage continued to turn up nothing, and, the more Hinricher heard, the less likely it seemed to him that the clubhouse was in fact the crime scene.

“They had it locked down,” Hinricher says. “They had checked ceiling tiles. They had done everything.”

Which led him to wonder: How was the equipment getting to and from the ballpark?

Here again the pandemic added a challenge: Normally, many equipment managers ride in the truck to the airport and watch workers load bags onto the team plane, so they know who’s touching what. But health and safety protocols forbade that.

On the morning of Sept. 21, the day after the Dodgers returned to L.A., Torres called the owner of the Denver company that drives team equipment to and from the airport to report the theft. That company had been using the same three drivers for years; the company’s owner spoke with the drivers and reported back: He was satisfied that they weren’t involved.

So, it wasn’t a custodian. It wasn’t a clubhouse staffer. It wasn’t a driver. That left ... no one, it seemed. But then the Rockies finally got to the bottom of who owned the eBay account that had been selling Sandoval’s and Cueto’s jerseys: a 44-year-old woman from Kent, Wash., named Julia Hylton. Along with her husband, Hylton runs an eBay account, Bidoncoolstuff, that sells everything from antique silverware to sports memorabilia. Hylton, who declined to comment for this story, had bought the baseball gear online, intending to resell it at a profit—hers were the eBay listings that Grems and his peers saw. Hylton told police that her husband bought his first jerseys on Mercari, an online marketplace, but for future transactions the seller moved the exchange to Facebook to avoid Mercari’s seller fees. And on Facebook, police now had not just a user name but a real name: Dakota Devon Reeves.

Hinricher immediately found Reeves’s Facebook account, which included a series of photos of himself at work.

At Denver International Airport.

As Hinricher would detail in his police report, Reeves worked for Menzies Aviation, at DIA, loading and unloading equipment for private charter flights. The 30-year-old had been there several years, restricting his unprofessional behavior to sneaking photos of athletes as they deplaned—which is when it occurred to him that maybe a few items could go missing from time to time without anyone noticing. To pull off his heist, Reeves wore compression tights under a pair of sweatpants. When he was in the belly of the plane he would open a team bag, root around quickly, find a jersey and stuff it inside the tights. The baggy sweatpants would camouflage the bumps.

Reeves usually hit teams only on their departure, but the L.A. series was the Rockies’ last home stand of the year, and this time he struck on both the Dodgers’ way in and their way out.

The final tally: from the Padres, two Tatis jerseys and a pair of Tatis’s batting gloves; from the Giants, one Cueto jersey, one Sandoval jersey and a Giants COVID-19 face mask; from the A’s, one No. 26 Matt Chapman jersey; and from the Dodgers, three Bellinger jerseys, three Betts jerseys, three Kershaw jerseys, one No. 17 Kelly jersey and a pair of Betts’s batting gloves. (The A’s had not noticed that Chapman’s jersey was missing, because he was injured.) That’s 15 jerseys, two pairs of batting gloves, a mask ... and a bag of jelly beans that Reeves had sent to Hylton with Cueto’s jersey. “The beans were in cueto’s bag,” Reeves had messaged Hylton and her husband. “Figured why not throw one in there lol.”

Reeves was charged with the theft of items valued between $20,000 and $100,000, a Class 4 felony. He had no prior criminal record and quickly agreed to a deal in which he pleaded guilty to thieving items of lesser value (a Class 6 felony—the lowest level) and accepted a year of probation.

“I think [Reeves] had a certain amount of remorse,” says Hinricher. “The more we talked about it, he just realized that he made a mistake. He was short on money. ... It was a pretty costly mistake.”

Reeves did not respond to a request for comment, but he did post on Facebook last March, writing that he had cleared probation and found a new job. “Applying this pressure,” he added, “has changed this minor setback and flipped it toward a MAJOR comeback. Best head space I’ve been in in a long time. Watch what I do next!”

What everyone else did next was go back to their lives. The teams printed new jerseys, and the players got new batting gloves. (Many of those players didn’t even know about the thefts; support staffs tend not to bother players with problems outside their control.) In the end, Grems told William Khoury Dillon, the chief deputy D.A. who prosecuted the case and a huge Giants fan, that he could keep the team’s recovered jerseys; but ethics rules prohibit prosecutors from accepting gifts, so instead they sit, along with the A’s and Dodgers memorabilia, in the Denver PD property office. If no one picks up the items in the next five years, police will destroy them.

Authorities never recovered the Tatis jerseys, which Reeves sold to someone other than Hylton. (Detectives were unable to trace that sale, according to the police report.) The missing brown Tatis jersey did later appear, though, on the website for a memorabilia company called USA Sports Marketing. Tatis had worn it when he hit his first career grand slam, which came on a 3–0 count with his team up 10–3 against the Rangers, and sparked a brief furor over baseball’s unwritten rules. Some time after Reeves nabbed it, the jersey made its way back to Tatis, who signed it, writing: 1st career g/s 8/17/2020 and i’m sorry i hit a grand slam! In the listing, Tatis is pictured holding the jersey and mock-pouting. The item was listed at $99,999.95, and a representative from USA Sports Marketing says that it sold for somewhat less than that price.

That closed one chapter. But in 2021, reports began to circulate among equipment managers that gear was going missing in another National League city. The situation was dire enough that, when the Giants arrived in town, the home team asked Grems and his staff to set a trap, by attaching tiny RFID trackers to bats. “I planted bats all over the place,” Grems says, laughing. But whoever it was didn’t strike—and seemed to go quiet in 2022. Which is why Grems does not want to be more specific about the location: That thief is still out there.