The Truths and Non-Truths of Max Scherzer’s ‘Sticky’ Suspension

The fallout from the Max Scherzer suspension is, to borrow a new phrase in the baseball vernacular, sticky-sticky.

Enforcement of how much is too much when it comes to sticky fingers remains a matter of umpire opinion. Umpire James Hoye let Yankees pitcher Domingo German off the hook April 15 because his hand was “tacky.” Four days later umpire Phil Cuzzi warned Scherzer after the second inning about a “slightly sticky, tacky” hand, then warned him in the third inning about a “sticky” glove and finally ran him before the fourth inning for a hand “far more sticky than anything that we felt.”

MLB officials are satisfied with how the situation was handled and have no plans to amend the protocols of enforcing the ban on sticky substances, according to multiple league officials. Some players are confounded by the level of tackiness that is allowable.

Says Scott Boras, the agent for Scherzer, “The fact of the matter is, I still don’t know sticky from sticky-sticky, so I can advise my pitchers. They’re all coming to me and asking, ‘What do I do?’

“You’ve got [pitchers] in cars with no speedometers. They’re riding with the flow of traffic, but they don’t know how fast they are going.”

Boras pointed to the history of Cuzzi, who has been involved in all three of the ejections since MLB’s ban on sticky substances began in June 2021. (It was Tom Hallion who ejected one of them, Caleb Smith. Cuzzi was on Hallion’s crew then.)

“He graduated magna cum laude from Sticky School,” Boras says.

Scherzer has his history, too. Angels visiting clubhouse manager Bubba Harkins told Sports Illustrated in 2021 that Scherzer was among his 15 to 20 clients who ordered tins of Harkins’s homemade sticky stuff, a combination of liquid pine tar, stick pine and rosin, to better grip the baseball.

Scherzer did not appeal his automatic 10-game suspension from his April 19 ejection, saying he considered it fruitless to argue before an MLB official who would consider a grievance.

“He had no intent to cheat,” Boras says.

Because of the judgment needed for enforcement, this is not the last such case of differing opinions. A pitcher who has an abundance of sticky substance on his hand or any other area, including his glove, is subject to search and ejection—whatever the source of that substance. It is up to the umpire what constitutes an abundance of sticky stuff—that’s the sticky-sticky gray area.

Keep in mind umpires have performed thousands of these routine checks over the past three seasons. They have context as to what anomalous sticky stuff looks like, even if, to Boras’s chagrin, there is no equivalent of a posted speed limit.

Until the next inevitable controversy, let’s—ahem—stick to the facts. Let’s throw judgment and narrative aside and look at the facts of Stickygate. Then you can decide for yourself what happened and why more disputes are coming.

Spin rates are not used to determine violations.

There are several problems with using jumps in spin rate to determine violations. For one, the players are not enamored with the idea of using off-field metrics to decide on-field discipline. For another, you can get anomalies. Braves pitcher Max Fried averages 2,170 rpm on his fastball, but had one fastball clocked at 3,596 rpm, the fastest-spinning fastball by any pitcher and more than 1,000 rpm faster than any other of his fastballs.

Moreover, spin rate can be fickle. While four-seam spin rates are generally unique and stable to the individual in the manner of fingerprints, they do have some variance. An increase in velocity, for instance, can boost spin.

Take the Rangers’ Jacob deGrom as an example. His four-seam spin rate in a game has varied from 2,180 in 2015 to 2,593 last season. That’s a boost of 413 rpm, or 19%. But deGrom threw 95 mph in that ’15 game and 98.8 mph in that game last year. Gains in strength and improvement in mechanics can alter velocity, and thus spin.

Where would you set the rpm increase limit before you get flagged? And using spin rates opens the possibility of a player getting busted for cheating when there is no physical evidence. It’s too dicey.

Spin rates alone tell only a partial story.

The truer measurement of ball flight is the relationship between spin and velocity, or SVR (spin to velocity ratio). The average MLB SVR is about 24.0.

Jhoan Duran of the Twins is the hardest thrower in baseball, with a four-seamer that averages 100.8 mph. But because his heater has below-average spin (2,172 rpm), his SVR is well below average (20.9).

There are many pitchers with below-average velocity fastballs that have much higher SVRs because they have great spin, which gives their fastballs better gravity-fighting “ride” that make them harder to hit. Those pitchers include San Diego’s Joe Musgrove (93.1 average velocity, 27.4 SVR), Tampa Bay’s Jason Adam (93, 27.9), Seattle’s Paul Sewald (91.4, 27.1), Houston’s Phil Maton (89.6, 28.4) and Colorado’s Kyle Freeland (88.5, 27.0).

The Mets questioned Musgrove’s pitches in Game 3 of the NL wild-card series last year. They could see during the game that his four-seam spin rate reached a season high 2,666 rpm, 111 above his average. But Musgrove’s SVR (28.4), the more telling metric, was lower than it was in a May 1 start (28.5) and not far off his season averages for 2022 and ’23 (27.4).

Before his ejection, Scherzer was checked twice by umpires and instructed each time to make modifications to comply with the rule.

After the second inning, Cuzzi told Scherzer his fingers were too sticky and instructed him to wash his hand. In the third inning, Cuzzi told Scherzer his hand was clean but, upon finding a sticky substance in the webbing of his glove, ordered Scherzer to switch gloves. Scherzer complied.

It was before the start of the fourth inning that Cuzzi and home plate umpire Dan Bellino ruled Scherzer’s hand was sticky enough to be in violation of the rule—without throwing a pitch. Boras says Scherzer initiated that check, proving his lack of intent to cheat. Bellino told a pool reporter Scherzer’s hand was the stickiest he had encountered in three years of running daily checks on pitchers—“far more,” Bellino said.

After touching Scherzer’s hand, Bellino’s fingers became so sticky he asked a bat boy to fetch him a towel between innings to try to wipe off the gunk.

O.K., maybe TMI.

Scherzer and Boras said the pitcher used alcohol to wash his hands.

Scherzer defended himself by repeating he used only rosin and sweat. Those are two legal substances—but only up to a point. Rosin can be considered an illegal substance “when used excessively or otherwise misapplied,” according to a March 16 memo sent to clubs. The admission of an alcohol wash introduces a third element.

The handwashing is a key moment.

Rosin and sweat can create tackiness and buildup, but another element can be used to produce extreme stickiness, such as sunscreen lotion (a favorite before the crackdown), soft drinks like soda or alcohol. Why did Scherzer use alcohol to wash his hands?

“Pitchers can’t use soap and water because it softens the tissues of the fingers, and that’s how you can get blisters,” Boras says.

Describing his actions, Scherzer told reporters, “I am in front of the MLB official that is underneath [near the dugout]. I wash my hands with alcohol in front of the official.”

The “MLB official” near the dugout is a part-time seasonal employee with no administrative authority.

The official is a gameday compliance monitor (GCM) who is “responsible for monitoring and reporting Club compliance with gameday requirements, as well as providing support to the sign stealing and use of electronic devices enforcement program,” according to an MLB job posting description. GCMs are paid $27.50 per hour. They are eyes and ears only for MLB. They report any violations but do not intervene.

Scherzer’s SVR in the second inning spiked to a 51-start high.

Scherzer Four-Seam SVR by Inning, April 19

Inning | No. | SVR |

|---|---|---|

First Inning | 17 | 25.94 |

Second Inning | 5 | 28.02 |

Third Inning | 4 | 25.99 |

(Scherzer’s SVR was 25.9 last season and is 25.4 this season.)

Scherzer’s SVR in that second inning marked the first time his SVR was at least 27.5 in any inning since June 2021, when the sticky substance crackdown began. It was after that second inning Cuzzi found Scherzer’s hand to be sticky and ordered him to wash it.

Scherzer’s average spin rate of 2,606 in the second inning was his highest spin rate of his 296 innings since the crackdown began.

It was up 230 rpm from the second inning of his previous start.

Scherzer reached 2,720 rpm on a fastball to Luke Williams in the second inning.

It was the highest rpm among 2,081 fastballs Scherzer has thrown since the crackdown began in June 2021 (including the postseason).

Scherzer’s spin rate was up, but his velocity was down.

Scherzer averaged 92.8 mph on his fastball in the second inning, equaling his lowest second-inning velocity in his past 55 starts. Last season he averaged 94.2 mph in the second inning, including 93.8 in April. Spinning the ball faster while throwing slower produces a higher SVR.

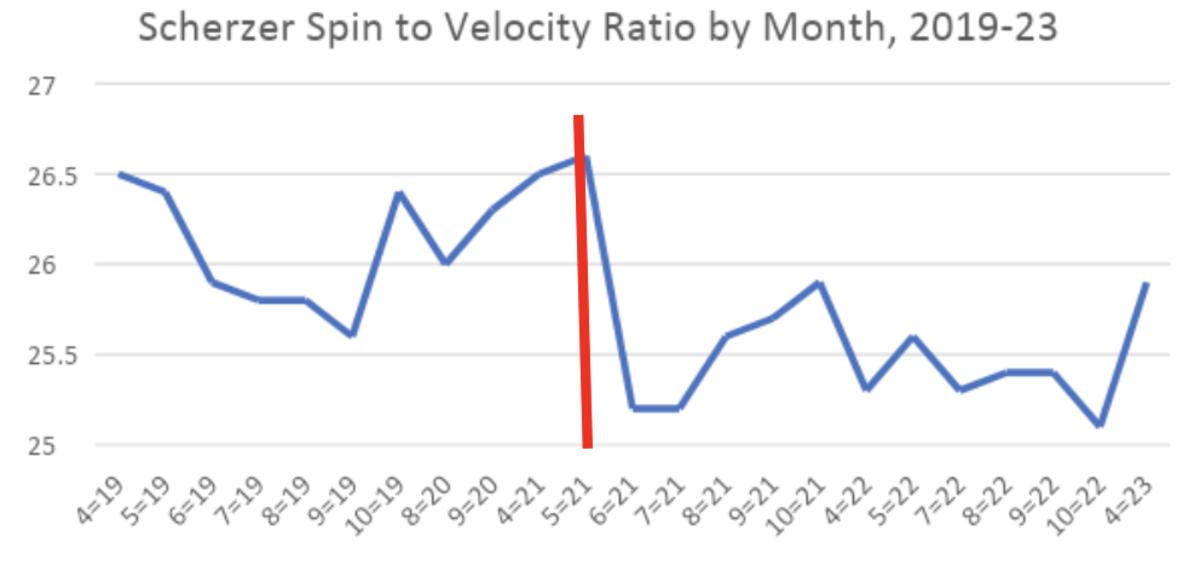

Until this month and since the 2021 crackdown, Scherzer’s SVR had been trending down.

Here are Scherzer’s monthly SVRs since 2019. The redline in the middle marks the start of MLB’s crackdown on sticky substances. His April increase from 25.1 to 25.9 marks his biggest monthly increase since the ’19 postseason.

Scherzer’s automatic 10-game suspension is outdated.

Pitchers rarely start on the fifth day anymore. What historically was intended to be a two-start penalty effectively has been cut in half. Scherzer will miss only one start.

Fifteen years ago, most starts were made with four days of rest (51.1%). That percentage has been dropping ever since, to 49.4% 10 years ago, to 37.9% five years ago, to just 23.7% this year.

An MLB source said the league proposed the automatic penalty to be set at 20 games to account for the rule’s original intention of penalizing a starting pitcher two starts, but the players association did not agree with the proposal.

Older pitchers are struggling with the new rules, which include a pitch timer and more rigid enforcement of the sticky substance ban.

Pitchers 36 Years Old and Older

Year | W-L | Ptc. | ERA | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2022 | 124–117 | .515 | 3.60* | .693* |

2023 | 14–28 | .333 | 4.93+ | .752+ |

*-Best of any age group | +-Worst of any age group |

MLB baseballs are too slick.

The answer to the Stickygate madness is obvious: baseballs with tackier leather.

A study this year by a professor of tribology (the study of friction) at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan, found the MLB baseball to be 20% slicker than the ball used by Nippon Pro Baseball. MLB baseballs are rubbed with mud before games. NPB baseballs have a tackier leather and are rubbed with sand. (Both leagues allow rosin.)

MLB has talked since 2017 about changing to a tackier leather and has experimented with spraying baseballs with a uniform substance to enhance grip. In 2018, MLB bought Rawlings, the manufacturer of the baseballs. It has made little progress in what should be a top priority.