The Family That Inspires the Rays

The bullpen catcher is unique in sports. He is not a player. He is not a coach. He squats in the bullpen before, during and after games, receiving pitches from anyone who wants to throw them. He calms over-amped relievers and reassures nervous ones. He helps pitchers feel important. He keeps track of what each one needs, physically and emotionally, and he provides it. He knows none of this is about him. His is a position of ultimate service.

When the broadcast flashes to an image of a reliever warming up, the bullpen catcher is sometimes in the shot, but off to the side. Every baseball fan knows he is there. But they never know his name. They never see his face. They never give him a thought.

The bullpen catcher is easy to miss. Until he is gone.

Carlos Ramírez is still licking his lips from his gigantic portion of brisket when the woman approaches. She is a Tropicana Field employee, and at first he barely notices her. But then she asks whether he is Jean’s dad, and he knows what is coming.

Her son tried to kill himself last year, she says. It was in part because of the resources the Ramírezes have shared that she was able to help him.

This is the best news Carlos has gotten since the last time someone told him something similar, a few weeks earlier. It serves as proof that he and his wife, Toni, have helped save someone. It is also a devastating blow. It serves as a reminder that they did not save the person they would most have wanted to.

Carlos thanks the woman for sharing her story and wishes her family well. Then, his face pale and his stomach churning, he dashes to the bathroom. An interaction like this often knocks him and Toni out “all day,” he says a few minutes later. But he does not have all day. He has about an hour. Sixteen months after Jean, the Rays’ bullpen catcher, took his own life at 28, the team is honoring Toni and Carlos for the work they have done to promote suicide prevention. Both the Rays and the opposing Yankees are wearing green ribbons on their uniforms in honor of mental health awareness month. The Tropicana Field jumbotron will play a tribute video.

So Carlos does what he has done ever since Jean died. He tries to heal the Rays, and he tries to let the Rays heal him. Carlos throws up, and then he throws out the first pitch.

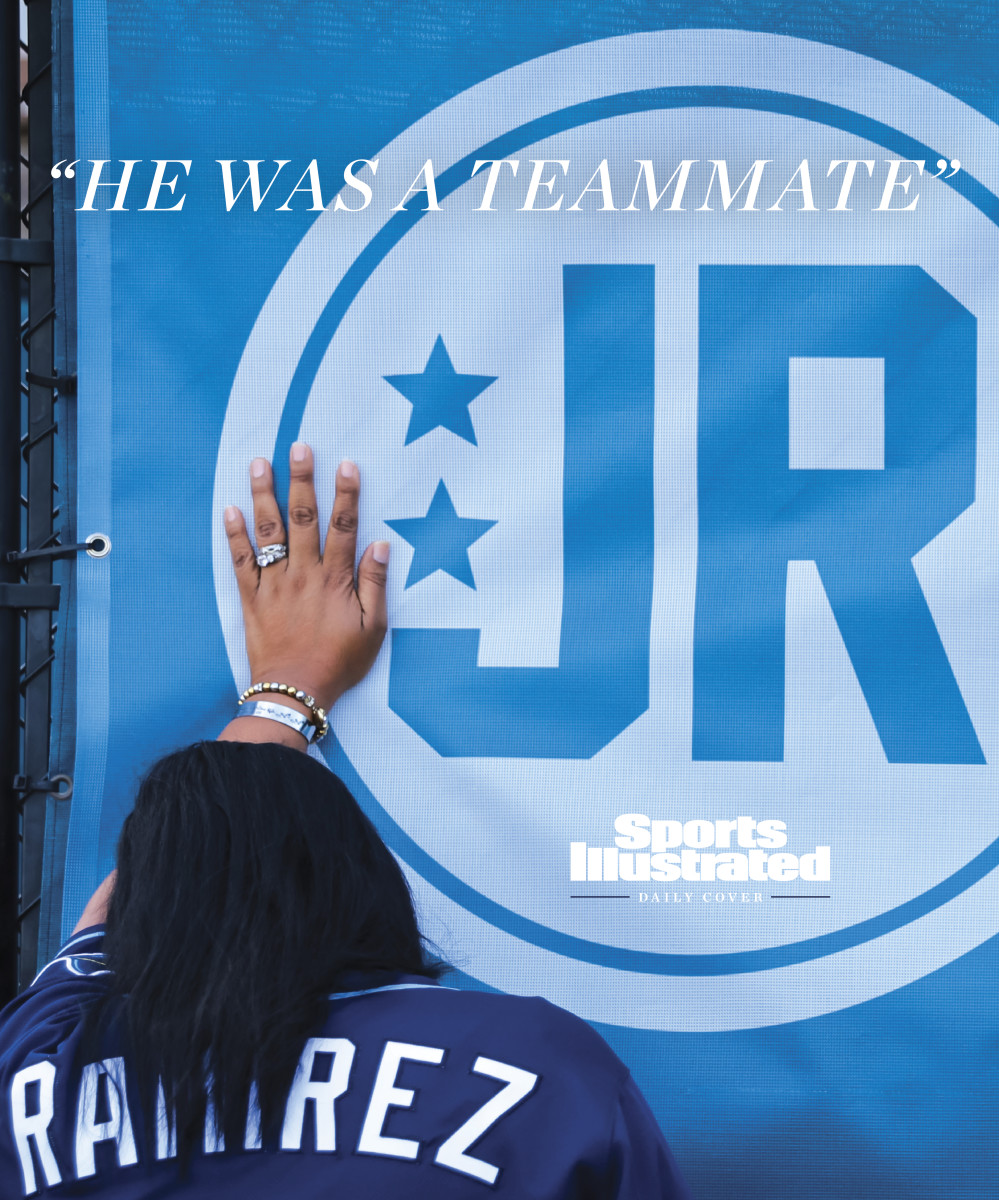

To the Rays, Jean was more than a guy crouching just out of the picture. “He wasn’t a bullpen catcher,” says manager Kevin Cash. “He was a teammate.”

No matter how determinedly the bullpen catcher relegated himself to the side of the frame, his friends saw him in the middle of it. They played golf with him. They shared dinners and drinks on the road. They looked for him when they arrived at the ballpark in the morning or early afternoon, catching a glimpse of his wide grin and smiling back.

In nearly every memory the people who loved Jean most can conjure of him now, he is beaming. As a 3-year-old running the bases after his dad’s Puerto Rican league games; as a college catcher playing for Arkansas, then Grayson (Texas), then Illinois State, transferring twice in search of playing time; as a 28th-round draft pick trying to make the Show; as a major league bullpen catcher who wore his No. 98 jersey with pride.

He topped out at Low-A as a player, not even enough of a hitter to be a glove-first catcher. But the Rays see the position of major league bullpen catcher as a first step toward a career as a major league coach or even manager. The idea is to get a promising candidate some big league experience, then send him down to the minors and let him work his way back. When a second spot opened up alongside Misha Dworken heading into the 2019 season, they had just the guy in mind.

Three of Jean’s Arkansas teammates—relievers Jalen Beeks, Colin Poche and Ryne Stanek—were expected to make the Rays’ roster that season, and Jean had caught pitching prospects Shane McClanahan, Shane Baz and Brendan McKay in the minors. Everyone had raved about Jean as a teammate. And the Rays had just released him as a player.

“I’m like, Man, this is fantastic,” says Kyle Snyder, the Rays’ pitching coach since 2018. “I mean, it’s an opportunity for a player to help kind of usher along former teammates that he has relationships with.”

Jean fit in immediately. He was the first to welcome a new player or staffer, echoing what his mom had told him when he got the bullpen catcher job.

“You made it to the big leagues,” Toni kept repeating. “You made it to the big leagues.”

Justin Su’a, the Rays’ mental skills coach, met Jean in spring training of 2019, their mutual first season in St. Petersburg, and was struck by that smile. “I remember thinking to myself, This is a very happy man,” he says, adding, “Sometimes you’re in this game for a long time and you can easily take things for granted. Jean didn’t take anything for granted. He appreciated the flights. He appreciated the weather. He appreciated the new gear. He appreciated the food. He savored things.”

Jean was a better bullpen catcher than he ever was a player, because the task demanded a selflessness that came naturally to him. In 2018, when McClanahan was promoted to the advanced rookie ball Princeton (W.Va.) Rays, he and Baz were discussing an annoying travel itinerary. Jean, then their teammate, volunteered to drive them to the airport, two hours each way, to make their days a bit easier. “Literally within a couple weeks of meeting the guy,” says McClanahan. “That was my first time really hanging out with him.”

Once Jean joined the major league staff, he kept looking for opportunities to help.

“He was always kind of what we needed him to be,” says reliever Ryan Thompson. “He was always looking after somebody else. He was always checking on guys in the bullpen. ‘What do you need? I’ll go in the clubhouse and get it.’ All that stuff was just above and beyond what his job entails.”

He threw batting practice to anyone who asked, even when he confessed to interpreter Manny Navarro, his best friend with the Rays, that he was exhausted. But there the bullpen catcher would be the next day, ready to do whatever anyone asked of him.

He served as team barber in 2020, buying a pair of clippers and inviting players to the balcony of his hotel room. And in ’21, he began painting cleats. Jean had always been a talented artist and something of a sneakerhead, and, when the rest of the Rays found out, they began clamoring for their own pairs.

And so he spent bus rides and flights watching video tutorials, then hours at home perfecting each brushstroke. “Here he is trying to really hone his craft,” says Su’a. “He doesn’t do it professionally, but if these major league players are saying, ‘Hey, take care of my shoes,’ he was going to do everything he could to the best of his ability.”

Perhaps because he had bounced around so much in his life, Jean always seemed to assign himself the task of making new guys feel welcome. He was born in Puerto Rico and grew up in Florida and then Texas before attending three different colleges. He would greet recent arrivals in their language, then help interpret for them so they could fit into the clubhouse.

Bobby Kinne, now the Rays’ coordinator of major league operations, transferred in June 2019 from the advance scouting department to the position of replay assistant. On his first day out of the front office and in uniform, as he tried to get his mind around his new clubhouse role, Jean approached him. “You look very confused,” he said.

“Instead of leveraging that against me, like some baseball people might, he was just like, ‘Let me help you,’” says Kinne. “‘Stand here. Do this.’ He was so great about that. When I was new, he looked out for me.”

And he kept looking out for him. Two years later, the Rays’ 2020 pennant win earned their coaches the right to staff the American League side at the All-Star Game. Jean was chosen to catch the Home Run Derby. He asked officials to extend the same opportunity to Kinne, who’d played infield in college. They agreed.

“In a moment where he was probably really excited and nervous, he spent his time prioritizing me,” says Kinne. “The best experience I’ve had in baseball was a direct result of his generosity and kindness.”

And he only teased Kinne a little when he let a ball get by him.

Jean had a talent for saying the right thing. Often when a pitcher gets shelled, his teammates leave him alone to stew. The bullpen catcher never did. Let that one go, he would say. Or he might identify a bright spot in the player’s outing.

“He goes out of his way to kind of get your head back on straight,” Thompson says. “If you lose it one-eighth mentally, you can spiral. Jean was really good about noticing guys that maybe were kind of in a rut, and he would be able to pull them out of that.”

He notes the terrible irony: The bullpen catcher needed help, and no one else noticed. No one else pulled him out.

Sports Illustrated spoke to more than a dozen of the people closest to Jean. All say they remain baffled by what happened to him. It is difficult in any case of suicide for those left behind to untangle the threads that led to that decision. But even in retrospect, the people around Jean have been unable to find the fabric. When they search their minds, they find no clues, only frustration. They are not aware of any evidence that Jean was experiencing depression. He shared no inciting incident. He left no note.

In early January 2022, Jean called his parents. He’d just broken up with his girlfriend but he said he was O.K. and wanted to come home for a couple of days. Toni was in Honolulu, where Carlos was an assistant coach with the Hawaii Pacific baseball team and she was a sixth grade teacher, but Carlos was at their house in Fort Worth, Texas. Carlos also works as a crew chief of ground services with American Airlines, so he put Jean on a flight to Dallas. A few days after Jean got home, he picked Carlos up from work. The car broke down, and they sat there chatting lightly while they waited for the tow truck. When they got home, they sat in the backyard smoking cigars, “talking about random stuff,” Carlos says. It could have been any of a thousand nights they’d spent together.

The next day, their younger son, Anthony, called Carlos at work and said Jean seemed a little off. Carlos called Jean, who said he was fine. They agreed that he’d pick his dad up from work at 2:30 p.m.

At 1:30, Anthony called again. “Dad,” he said. “Jean just walked out. And I saw a gun case on his bed.”

Anthony dashed to his car and searched the neighborhood while Carlos got someone to bring him home, alternating between calls with Toni and the police. “I was desperate,” Toni says now. “Can you imagine? Eight hours away.”

Carlos was still on his way home when he got a text from Jean, apologizing for not giving him grandchildren. Then Anthony told him: The police had found Jean’s body.

His parents could not understand how this could be real. Jean was so happy, so alive. They had no suspicions something was wrong, and now they had no idea what had happened. They say he was not distraught over the breakup. They say they would like to believe that he was overcome by some darkness and made a terrible snap decision, that he might have made a different one even an hour later. They will never know.

They decided “right away” that they wanted to be honest about what had happened, Carlos says. “Within minutes.”

Jean died on a Monday afternoon. Tuesday morning, Toni called Su’a and told him that Jean had died, by suicide. The Rays’ statement that evening said only that his death was “unexpected.” Toni and Carlos spent the next two days making sure Anthony, then 23, felt comfortable with the plan, then on Thursday, they publicly announced the cause of death, adding that they planned to honor Jean’s life by helping other families and that “struggling in silence is not OK.”

Toni and Carlos flew to Tampa to pack up Jean’s locker and apartment. As they drove his Volkswagen Passat home to Fort Worth, as they cycled through the grief and questions and exhaustion, a new fear gripped them. Jean’s life seemed perfect, Toni says. They began to wonder: How many of the other Rays are going through the same thing?

At that moment, the other Rays were scrambling. Among the brutal details of Jean’s death is that it occurred amid disputes over a new collective-bargaining agreement; the owners had locked out the players in December, meaning that per league policy, club employees could not communicate with players.

This manifested in a few ways. Socially, Jean was basically a player. According to United States labor law, he was management. So he found himself suddenly cut off from many of the people who had made up his daily life since he was in college. The isolation was challenging, he told Navarro. And many players felt the same way.

A week before Jean died, Poche tapped out a text checking in on him. The lockout was dragging on, but Poche felt sure the sides would reach a deal soon and spring training would begin. He wanted to tell his friend how excited he was to see him. But then he stopped. He was not sure what the penalty was for a team employee who broke the rules about communicating with players, nor was he sure what constituted communicating with players. Poche didn’t want to get the bullpen catcher in trouble. So he never sent it. He thinks about that decision a lot.

“It’s not like, Oh, if I sent him that text he wouldn’t have done it,” he says. “But I missed out on another chance to let him know I was thinking about him and I missed him and cared about him.”

No one blames the lockout for Jean’s death. But it did make the days that surrounded it more complicated. Tampa brass decided to ignore the rules for a moment. (“I don’t mind that this is part of the story,” says general manager Erik Neander. “If anyone has a problem with it, I don’t much care.”) Team officials notified MLB that they would be informing players of what had happened. They called as many people as they could, trying to start with Jean’s closest friends, then finally sent out an email and a notification on the Teamworks app that most clubs use to stay connected. The system was imperfect; second baseman Brandon Lowe found out from an ESPN alert.

But it gave them enough time to mobilize for the funeral. Toni and Carlos initially planned to hold the reception in their living room, until they heard that more than 200 people would be there, including almost a dozen Rays.

One after another, they hugged Toni and Carlos and burst into tears. Most of them had never met Jean’s parents. But they understood one another’s pain.

“They greeted us with open arms, as if we were their kids,” says Thompson. “We could just feel how much they cared about us.”

Poche says, “I think that was really important. One, for us, and two, to show his parents how much we care. A bunch of people made last-minute plans to hop on a plane because we cared about Jean. And you know, it hit the coaching staff just as hard. I was sitting at the funeral next to Kyle Snyder, and he’s the pitching coach—he spends as much time with Jean as anybody—and it hit everyone hard. It was just a good reminder that these people are all here for you and it’s O.K. to be vulnerable with these people.”

They just wish they had done more to show the bullpen catcher that he could be vulnerable with them, too.

After the funeral, they separated, the Rays players and staffers scattered across the country, Toni and Carlos and Anthony back to the three-bedroom ranch home full of memories of Jean. They could have left it there, grieved separately and tried to return to their lives.

But the Ramírezes quickly realized that they felt closest to Jean when they were around the Rays. And the Rays realized they felt closest to Jean when they were around the Ramírezes.

These days, Jean is everywhere at his parents’ house: Rays flag in the driveway, four memorials to him in the living room alone, his seat at the dining table marked by a framed photo. When there are more than five people over, they eat in shifts so as not to disturb it. His Tampa jerseys hang on nearly every wall.

The ones that are not framed are wrapped around Carlos, who wears them to Tropicana Field, occasionally drawing double takes from Jean’s friends, so similar are their mannerisms. Toni and Carlos make it to about a dozen Rays games a year, mostly in St. Petersburg. They watch all the other ones religiously on TV, recording any they miss live so they can play them later. (Some Rays employees joke that not even they catch all 162.) Carlos says he will keep coaching the Weatherford College Coyotes, who finished third at the junior college World Series, but this will be his last season with the summer collegiate league Port Angeles Lefties; he wants to spend more time following the Rays around.

“I lost my son,” Toni says. “But God gave me 40 sons.”

They make dinner for the team when the Rays play at the Rangers. They track not just team results but also individual ones, so they can reach out to anyone who might need a little support. When players struggle, they often check their phones afterward and find a text from Toni: “It’s just a game.” When former Ray and current Tiger Austin Meadows went on the 15-day injured list with anxiety this year, after a similar stint at the end of last season, Toni texted him to tell him how proud she was of him. They want every one of those young men to know they love them, no matter what. No more loose threads, no more missing fabric. When Toni asks how they are doing, she expects an honest answer.

“Sometimes we feel like, The boys aren’t playing good. Let’s go over there,” Carlos says.

They make the trip in early May, not because the Rays are scuffling—in fact, they are the best team in the sport—but because it is mental health awareness month, and the team has asked them to come throw out that first pitch. What might be a life highlight for someone else barely registers for them. All they want to do is hug their boys.

“You just kind of feel Jean’s presence when they’re here,” says Poche.

They hold court on the field during batting practice, accepting embraces from owner Stu Sternberg, Cash and so many players that they have to cut each conversation short to greet the next one. Even people who never knew Jean come to pay their respects, especially Charlie Valerio, who replaced their son as bullpen catcher. The first time they met, Carlos urged Charlie not to feel he had to live up to Jean; in fact, he said, Charlie should try to be even more successful than Jean. The Ramírezes would be rooting for him, they told him.

Valerio heard their words. But he does want to live up to Jean, he says: “For me, I represent him.”

Later that day, Toni and Carlos will wait in the tunnel outside the clubhouse, greeting players as they leave. Beeks will stride by, focused on getting home, when he catches sight of them and gasps in joy. Injured starter Tyler Glasnow, being driven through the stadium, will stop the cart so he can get off and visit. Navarro will make plans to eat lunch with them the next day at Jean’s favorite restaurant.

“There's so much turnover in baseball,” says Poche. “Each year, you get more and more players who weren’t here when he was here. Obviously coaching staff and stuff will stay the same. But I think for the guys who are here, it’s important to get something positive out of what happened and kind of [further] his legacy, because there’s people who don’t know him here. It’s a little sad to think things just go on as normal for a lot of people, but for some of us, we still think about it every day.”

Meanwhile, once or twice a month, Toni and Carlos relive the worst thing that ever happened to them. They return to that day in January, telling Jean’s story to anyone who asks and to plenty of people who do not. They first addressed the Rays just over two months after Jean died, flying down to spring training and giving talks to major and minor leaguers, in English and in Spanish. They told them about Jean’s life and about his death. They said that if the players didn’t have someone else to talk to, they could talk to them. They told them that when they looked at them, they saw Jean.

The sessions made enough of an impact—on both the players and on them—that they began repeating them elsewhere. They speak to college teams across the country. When they return to visit family in Puerto Rico, they hold a toy drive and speak to those children as well. Nearly every time they speak, about 10 times in all, they hear later that someone in the audience heard their message and sought help. That is the outcome they hope for. It leaves them broken.

“Everywhere we go, we talk as parents,” Carlos says. “Not as professionals, but as parents.” He adds, “We talk about what they leave behind.”

Jean left behind a million questions. Toni didn’t sleep for months, combing through every interaction she ever had with her son, wondering what he was telling her that she didn’t hear. She studied photos of him, looking for the moment a darkness appeared in his eyes. But then a friend of hers advised that she stop looking for answers. She was never going to find any that made sense to her.

The Rays are still searching.

“It hasn’t gotten easier, because nobody really knows, like, how did this happen?” says Cash. “Nobody gets it. Sometimes there's more pieces to the puzzle you find out a year later or two months later. That hasn't come out. Nobody understands.”

They wonder what they missed. “I was mad at myself for not seeing signs, if there were signs,” Snyder says. “You look inward. You try to figure out, What in the world? I consider myself to be a pretty compassionate person in the way I go about my life and my job and all that stuff, and not seeing it for what it was—the ministry of presence is so big in our jobs. It may not even be what you say, but just being there, and to me, I felt for a long time, like, What is it? I understand people well. I think that’s a lot of what provides me the ability to do my job to the degree that I do it, and not seeing that was something that baffled me for quite some time.

“I’m still confused. It kind of goes to a stigma with men, an unwillingness to share weakness. I feel like I’m approachable. I could’ve been a guy that he was willing to share some things with. But those are the things that have been frustrating. Because I feel like I have that relationship with a lot of the other players and guys that are down there that are willing to bring things to me that they may not be willing to bring to another coach that they've had in the past. I just wish I would have seen something that would have initiated a conversation.”

Many players and staffers wear gear bearing the logo of the JR98 foundation, which Jean’s parents set up to raise money for mental health resources. Every staff member took a mental health first aid course, designed to help them spot the signs of someone in crisis and direct them to a professional. The team also has as a resource a licensed clinical social worker, Vince Lodato, and after Jean’s death added mental health staff at every minor league level. Players carried Jean’s jersey to the bullpen before every game last year and placed it at his spot on the bench. A JR98 sticker marks that seat now, commemorating the man who calmed them and reassured them and made them feel important. And they try to prevent a similar tragedy by being more honest with one another about how they are feeling. Snyder says people have come to him this season to express concern about their own mental health. Kinne says he has begun speaking with a therapist. The bullpen catcher never told them something was wrong—but they never asked. So now the Rays ask one another how they are doing, and they listen to the answers.

“The hardest part is knowing that he was hurting and we weren’t there for him,” says Thompson. “So I think for all of us here, we’re letting that be a learning experience to be there for each other and to just kind of go above and beyond.”

That, they think, might be the best way to honor the bullpen catcher: Just as he did, they make one another feel important.