Inside Christian Yelich’s Remarkable Comeback Season With the Brewers

Christian Yelich is back. All the way back. Don’t just take it from me. Take it from Yelich himself.

“I still feel like the player that I was in ’18 or ’19,” the Brewers’ left fielder says. “I can still do that. I feel like I have been that player for the last couple of months.”

“The .600 slugging?” I ask him.

“I think that’s still in there. I think since May or June, it has kind of been that.”

Welcome to one of the most remarkable comeback stories of this season. Yelich has emerged from more than three years lost in the baseball woods to become an impact hitter again. The latest evidence was a walk-off single Monday night to beat Cincinnati, 3–2, and keep Milwaukee in first place in the NL Central. It was his first walk-off hit since ... 2019.

“Oh, he’s back,” Brewers pitcher Wade Miley says. “We see it. He is locked in and ready to go off.”

“Baseball,” says Milwaukee manager Craig Counsell, “is a team game. It’s not the kind of game where you typically say one player can go out and win a game for you. But we have two players right now who can do that: Corbin [Burnes] and Christian. They can impact the outcome of a game by themselves.”

The arc of Yelich’s career is virtually unprecedented, given the enormities of its rise and fall. He was one of the best players in baseball over the 2018–19 seasons—even historically great. He won one MVP and finished second in another while becoming the first player with 80 homers and 50 stolen bases in his age 26–27 seasons.

Watch the Brewers with fuboTV. Start your free trial today.

And then he crashed. Hard. The guy who slugged .631 in 2018–19 slugged .388 over the next three years. Don Mattingly, who tumbled quickly from similar greatness because of a back injury, was his rare comp for someone who fell so far so young. For Yelich, a broken kneecap in September ’19, the oddness of the COVID-19-truncated season of ’20 and a sore back in ’21 helped reduce him to a passive, groundball-hitting shell of himself. He lost the ability to drive the ball in the air. He hit 35 homers over those three down years, less than he hit in ’18 or ’19 alone.

His nine-year, $215 million contract extension acquired the bad karma of an albatross for the small-market Brewers from the moment it began in 2020. Yelich heard the criticism. He knew people expected more years like ’18 and ’19.

“You know, I was talking to some of our guys about this the other day,” Yelich says. “Like if you have to have an 1.100 OPS to be considered a success, that’s a pretty tough bar. You could be disappointed.

“It’s like, ‘Oh, man. Where's the 1.000 OPS? What happened?’ If that’s your benchmark, then you know, it’s a tough bar to set for yourself. But that’s kind of what happened. Coming here it was like my first two years was a 1.000 OPS and 1.100 OPS, and obviously the next few years I didn’t reach that. I didn’t have the years I wanted to, but ...”

“Did you feel responsibility to try to match those years?”

“I think that just kind of becomes like the standard for people. They just look at you and go, ‘Well, it’s just like a given, all right? You can pencil in a 1.000 OPS.’ And it's like, ‘No, no, no! That’s not how baseball works—for the greatest players you ever played—anything like that.’

“And I mean, I’m better than what I was showing the last few years, and you deal with some stuff ... get into some bad habits and then yeah, it gets to be kind of a battle. But I don’t really think anybody’s career is always smooth sailing.”

Yelich is one of 14 players in baseball history to post two qualified 1.000 OPS seasons by age 27. (Twenty-four others did it three or more times.) Seven of the 14 never did it again: Prince Fielder, Vlad Guerrero Sr., Nomar Garciaparra, Juan González, Babe Herman, Chick Hafey and Jesse Burkett. Careers are not linear.

“I think there are ups and downs,” Yelich says. “You’ve got to fight through adversity and make adjustments and changes. Even the best players who play this game have to make adjustments. You’ve seen it, right? Cal Ripken can have different stances all the time. Albert Pujols had different stances at the end. Like, yep, if these guys have got to do that, then so do you, you know what I mean?”

The inside story of how Yelich got his groove back is about one of those small but impactful adjustments. But first, you must start with his health. Back in 2020, Yelich cut his swing rate from 44% to 34%. Major league average is 47%.

“When you don’t have confidence you can do it, you don’t swing as much,” Counsell says.

This year he is back to 44%, his highest swing rate since 2019.

“I feel physically healthy,” he says. “I feel great, like my body and everything. It feels really good. But I think going through some of that stuff, I got in some bad habits. And then once I got healthy, I couldn’t get out of the bad habits.

“I got off to a pretty bad start in April this year. You’re in a little hole that you dig yourself and have to go from there.”

On April 23, Yelich managed a weak infield single in three at bats against Tyler Anderson, including a strikeout on three swings and misses, the last on a 93-mph fastball over the plate. He was hitting .232 and slugging .354. The next day, a Saturday, Yelich arrived early at American Family Field and headed to the indoor batting cage across the hall from the Brewers’ clubhouse. Inside that cage is where his comeback began.

Yelich typically hits with a leg kick that begins when the pitcher takes the ball out of his glove. Former teammate Mike Moustakas once described Yelich in the batter’s box as The Samurai and The Swan—The Samurai for the poised stillness of the warrior-like upright pose of his stance and The Swan for the grace of his movements as he sweeps the bat through the zone. But the exquisite flow and timing of his swing had stopped working.

In the cage, he replaced the leg kick with a toe tap. The trigger mechanism begins at the same time as the leg kick, but because the front foot and knee remain closer to the ground his body is more controlled and quieter.

“I stayed in the cage and then did it in the game that same day,” he says. “Took it right into that game.”

“And it felt good right away?”

“Uh, I mean, it felt all right. Any time you change something like that, it doesn’t feel super great right away. You’re constantly working at it.

“It’s just a little change. Nothing too crazy. But it’s just more about being more controlled with smaller movements and consistency. It’s about being on time, and then you can control your body a little better.”

Here is Yelich on April 28, when he was late on the 93-mph fastball from Anderson:

And here he is the next day against Reid Detmers after switching to the toe tap:

Yelich went 0-for-4 that night but felt the improvement in his timing and the simplicity of his movements. Counsell gave him the next day off as a two-day mental break (the Brewers were off the next day) after a nine-game stretch in which Yelich hit .172 with no home runs. His season average was down to .223.

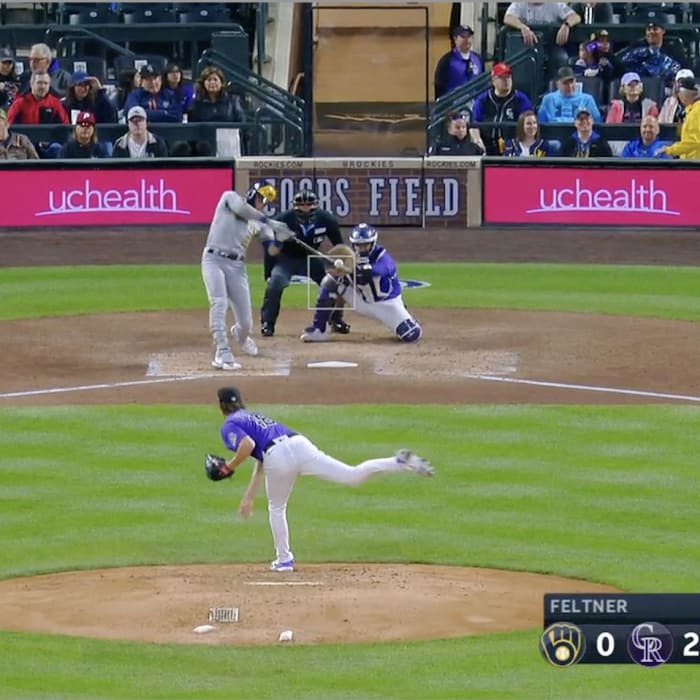

The Brewers’ next game was in Colorado. That’s when the affirmation happened. With the toe tap, Yelich scorched this ball at 109.5 mph for a double:

Thanks to the toe tap, Yelich was officially back. Here you can see the difference in his timing on similar pitches. In the strikeout on the left, Yelich is late. You can tell by the weak position of his back foot and leg. On the right, his backside is driving through the ball at impact, with the knee more bent and the heel raising because of the weight shift.

The snowball started rolling. The next day Yelich went 1-for-3, including a lineout to center field at 105.5 mph. The day after that he pounded three hits: singles at 96.9 and 107.7 mph and a home run at 107.8. He was on his way. Ten days later he smoked a home run off Jordan Lyles of Kansas City at 113.5. It was the hardest home run Yelich had hit since ... 2019.

The toe tap reversed the downward trajectory of his career. This year alone, the change is stunning:

Yelich 2023 Season Splits

G | Avg/OBP/SLG | HR | |

|---|---|---|---|

Thru April 28 | 26 | .232/.327/.354 | 3 |

Since with toe tap | 71 | .310/.395/.522 | 11 |

And once Yelich began to feel right, he began doing something he had not done consistently for years: pulling the ball in the air with power. In 2019 alone, Yelich hit 20 home runs to the pull side. He hit only 16 in the four seasons since, but three of those have come since he adopted the toe tap. Counsell says he sees Yelich “hitting the ball out front more,” which leads to more power.

“It’s not like a conscious effort to go the other way or to pull the ball,” Yelich says. “It’s just how it works out sometimes, but yeah, there’s been some pull home runs the last couple of weeks.

“You kind of realize like there’s not one way to go about hitting. Just because you’ve done it one way for a really long time doesn’t mean that’s the only way to do it. If you look around the game, it’s pretty evident because everybody hits different.

“So it’s like, ‘Why do you have to be married to this? Find a different way to go about it.’ Once you stop beating your head against the wall that’s a good attitude to have, man. The toe tap is a good example of that. It’s something small. It’s not like I did anything drastic. But it’s still different, you know? It takes some work, but I think if you want to play a really long time in the big leagues, you have to be able to adjust.

“You have to adjust throughout your career. I think it’s just like a natural career arc. Now I feel healthy. I feel great now physically. And I try and help these guys win every night.”

For three seasons and one month into a fourth, the same darn question dogged Yelich: Can he ever return to being even close to the star he was in 2018 and ’19? Since he went to the toe tap, and especially over the past six weeks as he has grown comfortable with the change, Yelich has provided the answer. Here it is in statistical form:

Yelich Comparison

Avg. | OBP | SLG | OPS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2018–19 | .327 | .425 | .621 | 1.046 |

Since June 11 | .348 | .423 | .623 | 1.046 |

The answer is right there. Yelich is back. It is also there in every swing when he catches the ball out front and sends it screaming through infields or over outfield walls. And it is also there in the certainty of his voice when you ask him whether he can be that player again: “I can still do that.”