Nothing Reveals More About a Pitcher Than His Decision on a Full Count

In 1924, a doctor in Ferris, Texas, who specialized in obstetrics noticed a certain drug prevented patients from creating rationalizations. The patients revealed only what they considered to be true. Robert Ernest House discovered what soon came to be known as “truth serum,” often known under the trademarked name Sodium Pentathol.

The full count pitch is the Sodium Pentathol of pitching. It reveals the truth about what a pitcher feels about his stuff. When you have exhausted the tree of possible pitch counts to its last limb—when there are no more pitches to waste and you must throw a competitive pitch—what will you throw? Your choice says much about who you are as a pitcher.

I’ve long been fascinated by full counts. I remember how Bobby Valentine, after managing in Nippon Pro Baseball, said the full count was regarded with such honor in Japan that pitchers strove to steer at bats toward the 3-and-2 pitch. It is considered the epitome of the art of war between the pitcher and batter.

Watch MLB with fuboTV. Start your free trial today.

Think of your backyard dreams as a kid. What was the count in your mind’s eye when you hit that winning home run in the World Series? Full, of course—same as it was for Kirk Gibson and Derek Jeter in real life.

Whenever I broadcast games, I make sure to have on hand a pitcher’s full count history. Never mind what I think of your stuff. What do you think? The full count pitch reveals it.

Last Saturday, for instance, I knew heading into a Red Sox–Yankees game that Gerrit Cole of the Yankees throws his four-seam fastball 75% of the time on full counts, the kind of overwhelming percentage hitters love to see. Sure enough, Cole threw six pitches on full counts, and every one of them was a fastball. Not once did he get strike three. Connor Wong smacked the last one for a two-run homer.

What does it tell you? With pride and confidence, Cole will go to his fastball when he needs a pitch. And Boston could sell out for it.

Max Scherzer, on the other hand, throws his four-seamer only 44% of the time on full counts. In 2016, when he threw harder and won his second Cy Young Award, he used his fastball 66% of the time on full counts. The truth serum in his case tells you he doesn’t trust his fastball as much, has growing conviction in his changeup and slider, and does not mind walking batters in certain spots.

Here’s another bit of truth serum: James Paxton of the Red Sox should throw his fastball more. He throws it 55% of the time until he gets to a full count, then chooses his heater 64% of the time in full counts. The result? He has allowed the lowest on-base percentage this year among pitchers who have faced at least 50 batters in a full count (.321, tied with Zack Greinke). The revelation from the truth serum for Paxton: Trust your fastball more. It’s working when you must throw a strike.

Surprisingly, Framber Valdez of Houston is the worst pitcher in baseball on full counts (.426/.581/.630). Why? He elevates his favorite pitch, the sinker, to the middle of the strike zone rather than keep it on the edges and risk a walk.

Who has the edge in full counts, the pitcher or the hitter? The pitcher has a huge edge when it comes to preventing hits. But if you define “winning the war” of full counts as getting on base, the hitter has the big edge.

Batters this year are hitting only .190 on full counts—the lowest in any full season since pitch tracking began in 1988. But their on-base percentage is .455, only the 11th lowest in those 45 years.

Only on 3–0 and 3–1 counts are hitters more likely to get on base. And here’s how much pitchers should avoid getting to a full count: If a 2-and-2 pitch is a ball, the hitter’s probability of getting on base jumps from 18.3% to 45.5%. That should be a huge incentive to challenge hitters at 2-and-2.

But what qualifies as “challenging” a hitter these days? We know despite rising velocity there are fewer fastballs in the game today than ever before. In just the past five years, the percent of fastballs (not including cutters) has dropped from 55% to 47%.

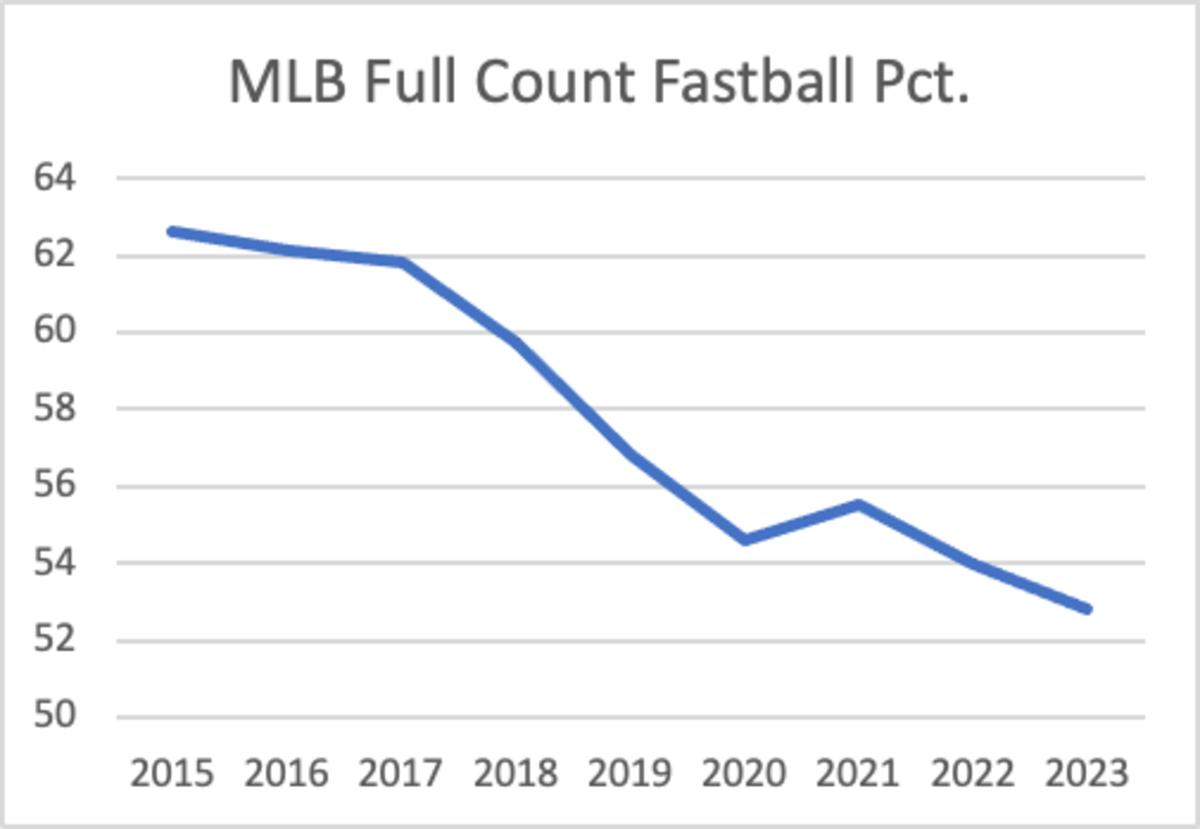

A similar decline is happening in full counts. Eight years ago, a hitter could expect a fastball 63% of the time in a full count. This year it’s a veritable flip of a coin as to what’s coming: 53% fastballs. The decline of throwing fastballs in full counts has accelerated in the past five years:

Is it working? That is, is the trend away from fastballs when you “must” throw a strike allowing pitchers to win those battles more often? Yes and no.

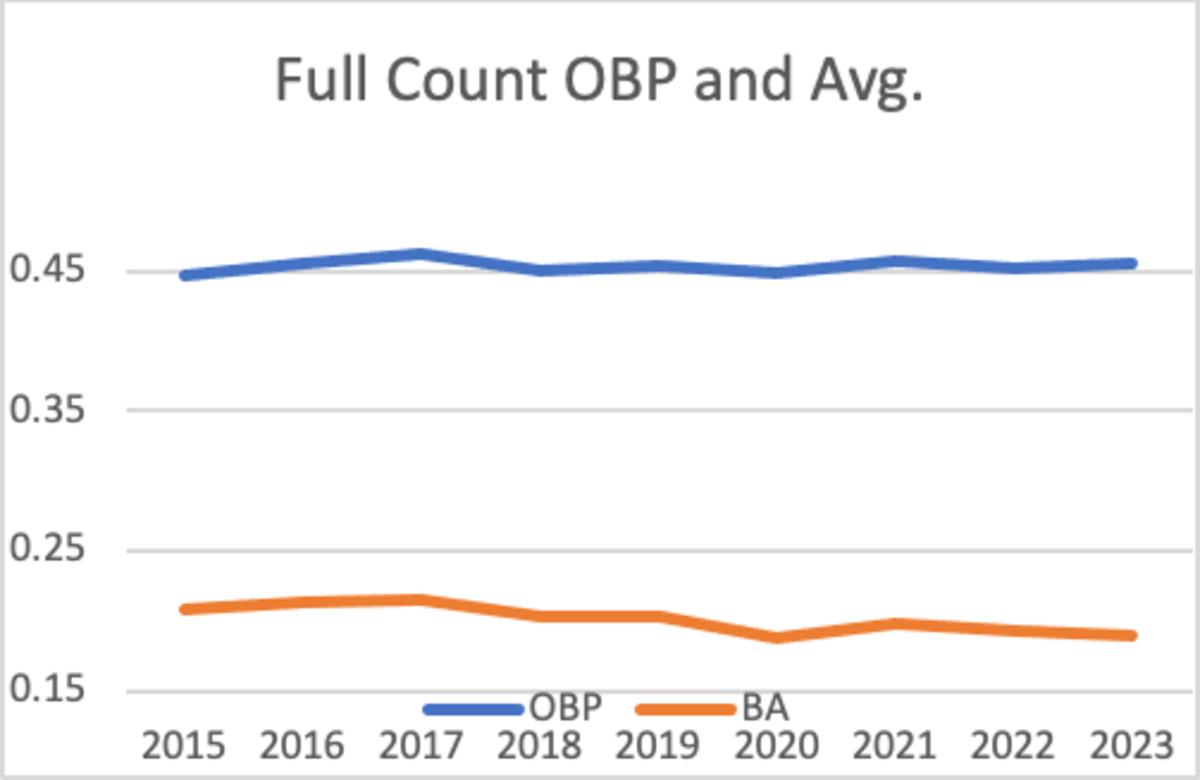

Again, throwing fewer fastballs in full counts is reducing hits to levels not seen since 1988:

Lowest Average in Full Counts Since 1988

Avg. | ||

|---|---|---|

1 | 2020 | .188 |

2 | 2023 | .190 |

3 | 2022 | .194 |

4 | 2021 | .199 |

5 | 2019, 2018 | .203 |

Full count batting average has dropped from .216 in 2017 to .190 this year. Slugging is down to a record low this year in full counts (.325, tied with last season for the worst since 1988).

But all those nonfastballs are leading to more walks. The on-base percentage in full counts has remained steady despite fewer hits:

Despite the pitch timer and the ban on shifts, the game still pivots more on home runs than anything else. And throwing more nonfastballs in full counts—not “challenging” hitters—is part of this passive-aggressive defense of the home run. A common tenet of pitching today is “a walk is not a bad play.”

It should not come as a surprise to know that this “defending the home run” mindset is leading to more full counts:

Plate Appearances Reaching Full Counts

2023: 14.1%

2013: 12.8%

2003: 12.2%

1993: 11.1%

It takes a certain kind of pitcher to excel in full counts. It takes someone who can throw multiple pitches for strikes. You can see that common thread in this list:

Lowest OBP Against, Full Counts Since 1988 (min. 1,000 PA)

1 | Greg Maddux | .376 |

|---|---|---|

2 | Dan Haren | .394 |

3 | Zack Greinke | .401 |

4 | Mark Buehrle | .402 |

5 | Pedro Martínez | .404 |

On the offensive side, high-contact hitters who control the strike zone tend to fare best on full-count outcomes:

Highest OBP, Full Counts (min. 500 PA)

1 | Quilvio Veras | .561 |

|---|---|---|

2 | Nick Johnson | .554 |

3 | Tim Raines | .553 |

4 | Barry Bonds | .552 |

5 | Dave Magadan, Larry Walker | .549 |

That seems an eclectic group, but Veras posted a career on-base percentage of .372 and walked almost as often as he struck out. He hit only 32 career homers in seven seasons but was the most difficult hitter to put away in full counts.

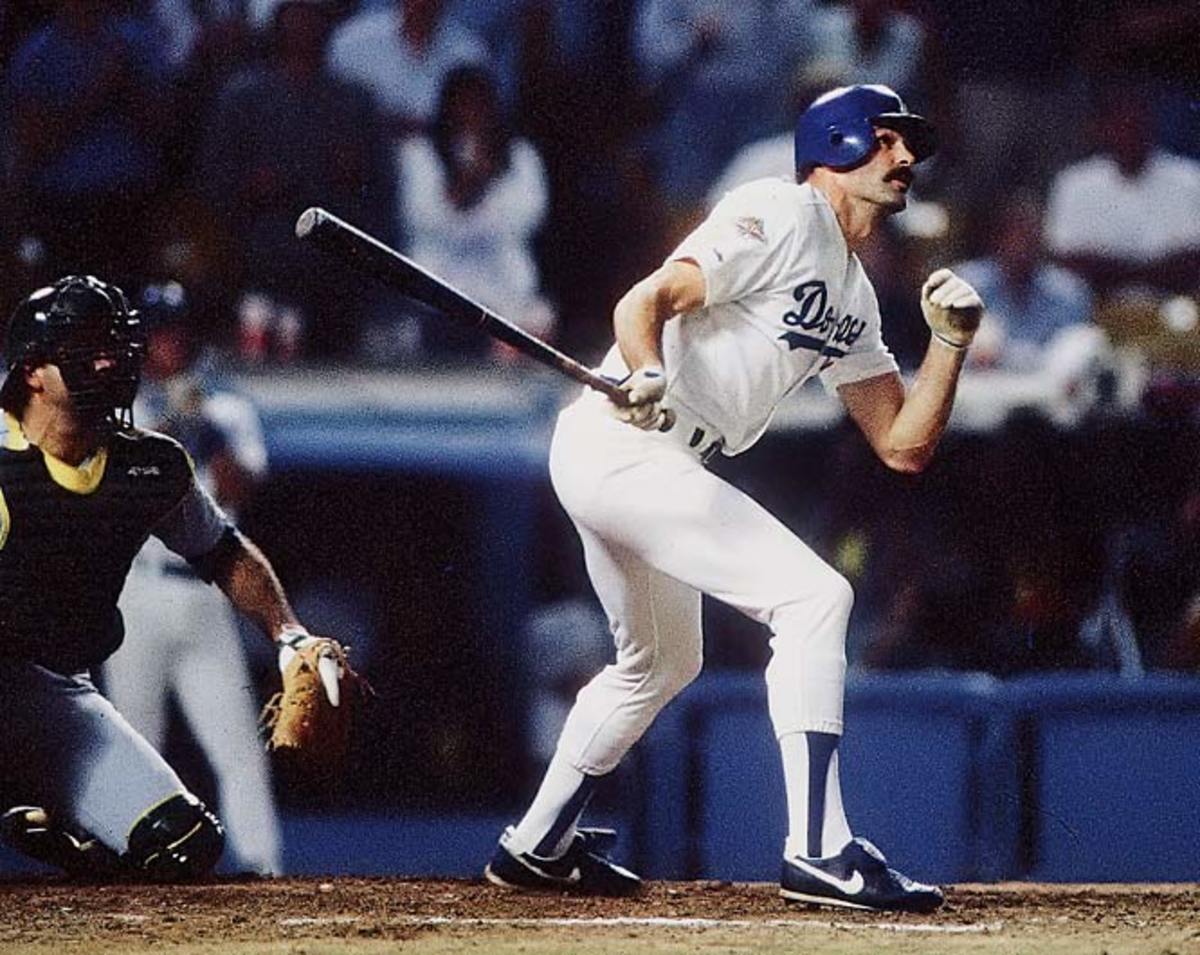

The full count is the batter-pitcher confrontation pushed to the brink, especially late in a close game. The full count added drama—and a classic backstory—to the Gibson home run in Game 1 of the 1988 World Series.

On the eve of the game, three left-handed Dodgers hitters, Mike Scioscia, Mike Davis and Gibson, sat on the floor of the clubhouse with their backs against the wall as they listened to scout Mel Didier give his report on Oakland’s pitchers. Didier had been watching the A’s for a month. He ran through the Oakland pitching staff one by one, finishing with Eckersley, the closer.

Didier pointed at the Dodgers’ lefties and said, “Podnuh, let me tell you this: If Eckersley gets you at 3–2 and there’s a runner at second base or third base and it’s the tying or winning run, Eckersley will throw you a backdoor slider on 3–2. Don’t forget that, because that’s what he will do as sure as I am standing here breathing.”

Didier later said he had seen Eckersley do it only twice, “but I felt confident enough to tell them.”

In fact, Eckersley went to a full count against a left-handed hitter only eight times all year, regardless of game situation. Four of those occasions happened in May, when Didier would not have been scouting Oakland. Only one of them happened since Sep. 17. In Game 1 of the American League Championship Series, Eckersley had a full count to a left-handed hitter Rich Gedman with the tying run at second base—the exact scenario in which Didier told the Dodgers’ hitters that Eckersley would throw a backdoor slider “sure as I’m standing here breathing.”

Eckersley did not throw a backdoor slider. He threw Gedman a fastball. It missed off the plate for ball four.

Gibson didn’t know that when he called timeout with the count full. Eckersley had thrown 17 straight fastballs. Gibson knew only what Didier told him.

Said Gibson, “I said to myself, looking at Eckersley, ‘As sure as I’m standing here breathing, you’re gonna throw a backdoor slider.’ Then I stepped back in.”

Gibson widened his stance and told himself to shorten his stroke. Eckersley threw a slider. Gibson hit it out. As he rounded third, he screamed at third base coach Joey Amalfitano, “Backdoor slider!”

Nineteen eighty-eight was the first year of tracking pitches by count. Eckersley was such a premier strike thrower he had gone to a full count only 21 times all season—just 7.5% of the plate appearances against him. He had held batters to a .133/.381/.133 slash line in full counts. It would be another eight years before Eckersley gave up another home run on a full count pitch.

The tension of a full count also helped give us the at bat of the year: Shohei Ohtani pitching to Mike Trout with a one-run lead and two outs in the ninth inning of the WBC final. One slider and four fastballs brought the count to 3-and-2.

Trout would later say, “He didn’t throw me a split that whole at bat. That was in the back of my mind.”

What pitch would Ohtani throw at 3-and-2? Ohtani can throw his fastball 100 mph. But in full counts the previous season, Ohtani threw only 24% fastballs. When pushed to the brink in counts, Ohtani’s favorite pitch is the sweeper, which he threw 58% of the time in those spots last year. He remained true to his favorite pitch against Trout with the WBC on the line. In terms of velocity and break, it was the nastiest sweeper Ohtani has thrown in the big leagues. Trout swung and missed.

Think about everything behind that pitch. At 3-and-2 and the game on the line, a pitcher who can throw 100 mph opted to throw a nasty breaking pitch rather than a challenge fastball. As trends go, it was the Sodium Pentathol of pitches in today’s game.