Scherzer vs. Pfaadt: What to Expect from the World Series Game 3 Pitching Matchup

PHOENIX — World Series Game 3 looks on paper like a decided pitching advantage for the Rangers: Max Scherzer going up against Arizona rookie Brandon Pfaadt. One guy has won the Cy Young Award three times. The other has three round trips to Reno—just this year.

But this being the upside-down World Series—the first one with two teams two years removed from losing 100 games—the matchup is not what it seems to be. After three demotions to AAA, Pfaadt takes the better stuff into this game.

This is the inside story of how Pfaadt went from a commuter on the Reno shuttle to Game 3 of the World Series.

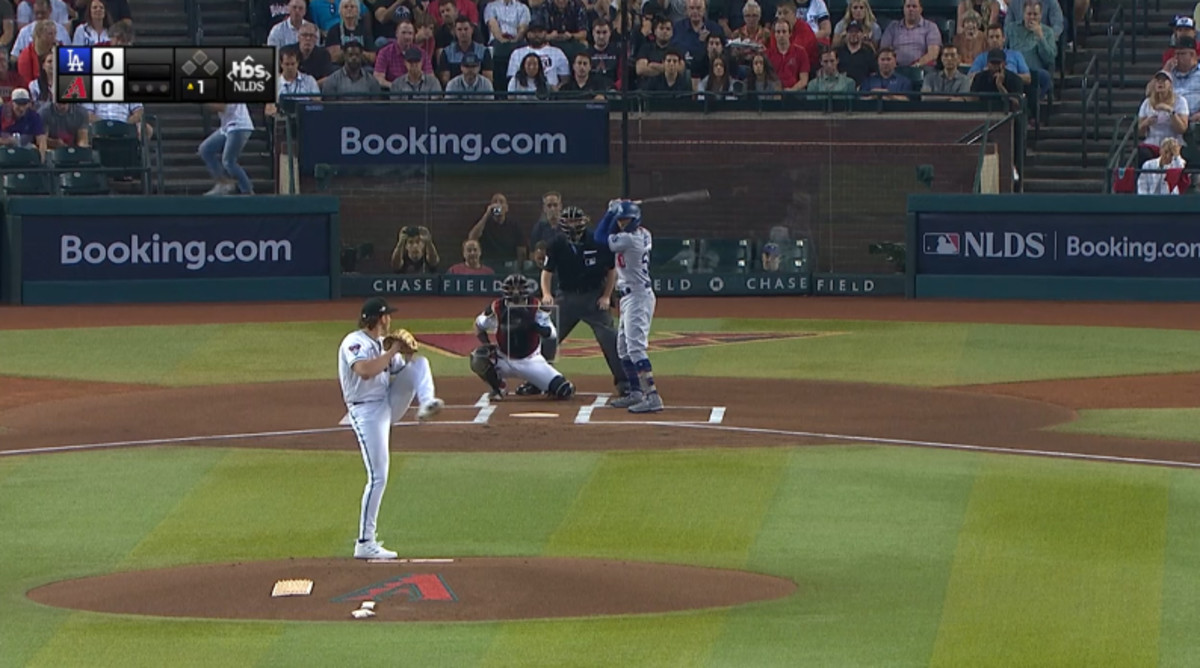

While Scherzer is still knocking off rust from his 36-day break caused by a teres major strain, the D-Backs are 4–0 this postseason when Pfaadt takes the ball. He has started games under pressure each time: the first game of the postseason (ALWC Game 1), the NLDS clincher against the Dodgers (Game 3) and two veritable must-win games against the Phillies (Game 3, down two games to none, and Game 7). Now he gets the ball with the World Series tied at one game each.

In his four starts, constrained by a quick hook from manager Torey Lovullo, Pfaadt has no decisions, a 2.70 ERA and, most impressively, only three walks against 22 strikeouts.

Pfaadt, 25, is a former fifth-round pick out of Bellarmine University, only the third pitcher to reach the big leagues from that Louisville school (Brad Pennington and Todd Wellemeyer). The D-Backs sent him down first when he did not make the Opening Day roster as a non-roster invitee, a second time May 27 after he made five appearances and a third time June 30 after one appearance.

Pfaadt is an elite mover with hyper flexibility. He has 80th percentile extension (letting the ball go nearly seven feet in front of the rubber) with a low release point (about 5.5 feet off the ground), a combination that gives superb ride to a four-seamer with average velocity (93.7 mph). It’s a tremendous physical package to confuse hitters, but Pfaadt needed refinement. Pitching coach Brent Strom kept giving him homework assignments each time he went back to the minors.

Lesson No. 1: Throw fewer fastballs.

Pfaadt could whiz his riding fastball past AAA hitters, but MLB hitters have slugged .650 against it. He has cut his fastball use from 45% in the regular season to 41% in the postseason. The better mixture of pitches is working. Batting average against his fastball has dropped from .325 in the regular season to .238 in the postseason.

“All of a sudden you get your ears pinned back [in the majors] and so he had to make an adjustment in terms of [using] his off-speed pitches,” Strom says. “Get him to use his curveball a little bit more to lefties. Then the changeup. The changeup was the biggest thing for me.”

Lesson No. 2: Make your pitches more competitive.

This is the key move. Strom made this adjustment with Pfaadt after his third demotion: He moved the righthander from the third-base side of the rubber to the first-base side of the rubber.

Why? With his lower, slingshot arm slot, Pfaadt was releasing the ball in line with the chalk of the right-handed batter’s box. He wasn’t getting enough chase swings because hitters did not see the ball starting in the zone. By moving a foot to the first-base side, Pfaadt released the ball so that it was in line with the strike zone as it left his hand. Now, hitters would need to read whether the pitch that began in line with the zone stayed straight (four-seamer), moved right (two-seamer), left (sweeper) or down (change and curve).

“He was kind of like a golfer who has a slice,” Strom says. “What do you do? You move in the tee box.

“When he was on the third-base side, everything was not on the plate. Here, my whole thing is forcing the fastball coming in [the zone], speeding up, and changeups right behind it going down, curveball going down and sweeper going that way. So basically, it’s just creating this separation. That's what I was trying to get. Over here on the third-base side, I couldn't do it. It's not even starting on the plate.”

The change is dramatic because of how every pitch looks competitive out of his hand. He is forcing hitters to make more swing decisions, especially more difficult swing decisions. That’s exactly how Merrill Kelly shut down the Rangers in Game 2.

Check out these two fastballs from Pfaadt here: the ones on top from June 29 (the day before he was sent down a third time) and the ones below from NLCS Game 3.

On the left side, notice the big difference in the placement of his plant foot on the rubber, and on the right side the difference in where the ball leaves his hand in relation to home plate.

One more change: this time without going to the minors, and the sharp-eyed among you may have caught it in the above pictures. More impressively, it was done by a rookie in between postseason starts.

Pfaadt had a habit of pulling the ball out of his glove at the top of the delivery and then putting it back in as his leg came down. Showing the baseball at any point in a delivery can sometimes lead to pitch-tipping in this age when teams use AI and base coaches to decipher any “tells.”

Using his usual “ball-out-of-glove” timing mechanism in Game 1 of the Wild Card series against Milwaukee, Pfaadt gave up three runs on seven hits. Here’s what it looked like in that game:

And here’s what it looked like in the first inning of his next start, NLDS 3 against the Dodgers:

The ball stays in the glove until the front leg has come down and kicks out. Since then, Pfaadt has a 1.29 ERA and has held batters to a .170 batting average. He is keeping the ball hidden from cameras and base coaches.

It’s easy to see why Arizona has so much confidence in Pfaadt. He has taken his physical gifts of elite extension and low arm angle and refined his delivery over the past seven months, even of it took three trips to the minors without complaint.

“I think the hardest moment was definitely getting sent down,” Pfaadt said, meaning especially the two times after the season began. “That's going to be hard for everybody. It all depends on the way you take it, which road you want to take.

“And I chose the road to the positive mindset and go down and work on things, get better and here we are. It all paid off.”

Says Strom: “He’s a young man who’s not flustered by it too much. He took his emotions great. When he’s getting his brains beaten in, he did a lot better than I would have. Yeah, he realized that he needed to make some changes and adjustments, and he has.”

The Scherzer Story

Scherzer should be better after making the equivalent of two rehab starts that followed five weeks off. He has thrown 63 and 44 pitches in those two starts. The arm strength is there; velocity is good.

Two big questions remain unanswered heading into Game 3:

1. Does his slider have bite?

Scherzer has only two swings and misses on his slider in his two postseason starts. When you compare his postseason slider to the one he had in August, you can see the pitch is rolling more than it is biting. It has less vertical movement and what is the most horizontal movement on his slider since he pitched poorly against San Diego in the postseason last year. (He would rather have the movement be sharp and late so that it presents as a fastball.)

Scherzer Slider

Avg. | Vertical Movement | Horizontal Movement | |

|---|---|---|---|

August | .111 | 1.9 | 3.1 |

Postseason | .500 | 1.6 | 5.1 |

2. Does he trust his changeup?

So far, the answer has been “no.” Scherzer has thrown only six changeups out of 107 postseason pitches, or 6%, down from 15% in August.

Those six changeups average the least depth on his change in the past four years. Weirdly, the only two changeups he threw to lefties (Yordan Álvarez and Kyle Tucker of Houston) moved toward the hitter.

Scherzer’s changeup to lefties should be a weapon for him; he threw it 17% of the time and held them to a .210 average in the regular season. He has yet to show his confidence is back with that pitch.

This is a huge start for Scherzer. He has the pedigree that Pfaadt does not, but he must quickly find the feel for his two best secondary pitches to be effective. Then there is the matter of his postseason record. Scherzer’s teams are 14–15 when he pitches in the postseason, 10–14 when he starts. In his past four postseason starts, Scherzer is 0–2 with a 9.19 ERA (16 earned runs in 15 2/3 innings).

With Arizona running a bullpen game in Game 4 and Texas likely starting Andrew Heaney, Game 3 presents itself as a huge swing game in the series.