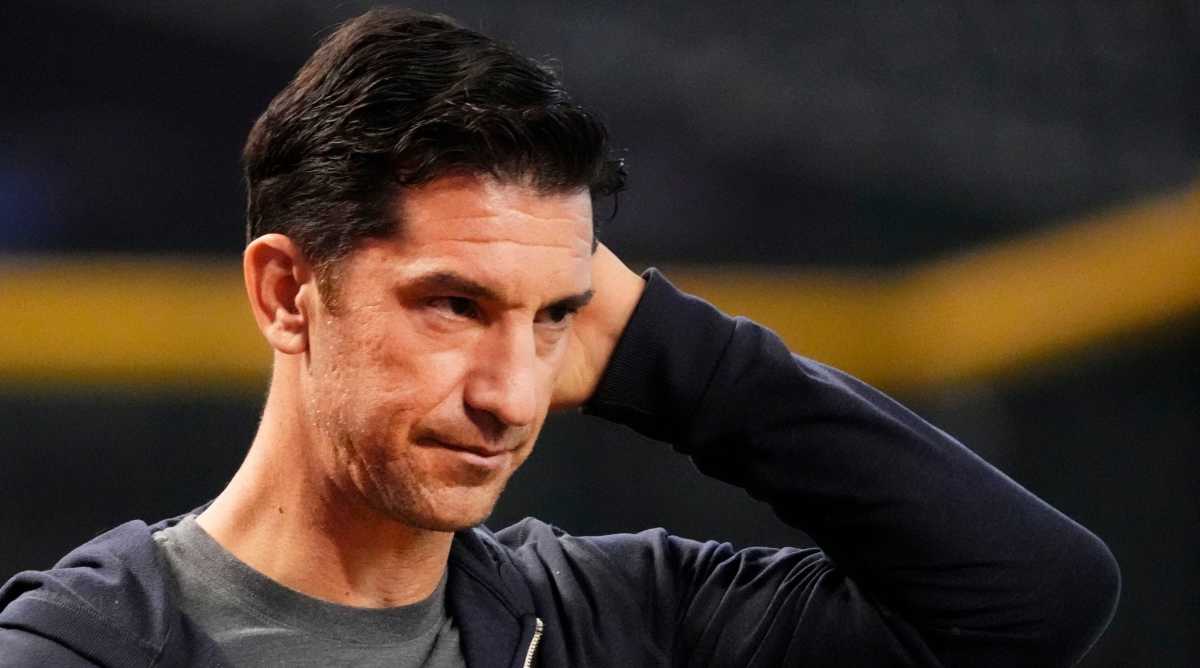

Diamondbacks’ Mike Hazen Might Be the Most Superstitious GM in Baseball

Something terrible happened to Mike Hazen on Saturday: The Diamondbacks roster he assembled won Game 2 of the World Series. The victory marked the latest step in a dream Hazen has been building since he arrived here before the 2017 season. It also created a real problem for one of the most superstitious people in a sport built on delusion.

Historically, Hazen has not permitted himself to watch the end of games. He catches the first eight or eight and a half innings in a suite with his assistants, watching the Diamondbacks hit live and pitch on TV, then he flees into the bowels of the ballpark for the final three outs. Ideally he would cocoon himself in a dark room, wearing noise-canceling headphones to block out the crowd roar, waiting for the post-game text from his mother-in-law, Phylis Ferrara, who informs him of a win. If the team loses, he does not find out until the players trudge back into the clubhouse.

With just a few outs remaining in Game 7 of the National League Championship Series last week, manager Torey Lovullo hurried to the bathroom in his office. He opened the door to find Hazen there, with the lights off, sitting on the seat of the shower “with headphones on, staring at what looked like a blank computer screen,” says Lovullo, his voice conveying something between pity and horror. (It wasn’t blank, Hazen insists. He was reading. He declines to say what.)

But Hazen followed his usual routine during World Series Game 1, and the Diamondbacks lost after the Rangers hit a game-tying home run in the bottom of the ninth and a walk-off in the 11th. So during Game 2, he went down an inning early, and he watched the end of the game, and it worked.

“I’m very fearful of what’s gonna happen moving forward,” Hazen says. “Because now that I’ve done that and we’ve won, I don’t know that I can go back to the way it was.”

He knows this is ridiculous. He knows it. And yet … “I wear the same pair of shoes until we lose and then I switch shoes,” he says. “All season long. I think what I wear, how I drive, what route I take, has a direct impact on the outcome of the game.”

He switches chairs in the suite when the opponent scores. He changes sport jackets and pants and socks after losses. He refuses to be specific about his laundry schedule.

“I wash my clothes,” he says. “I don’t wash all my clothes.”

Every game day since August, he has listened to country singer Morgan Wallen’s new album, One Thing at a Time. “The only days that I’m allowed to listen to something else are off-days,” Hazen says. “I like a lot of other songs on my Spotify playlist. But I can’t listen to them.” (His Spotify Wrapped, the data the music service makes available each December to its listeners about their habits, is going to be a bloodbath.)

He has trained the people in his life not to bother him during games. “I don't want texts,” he says. “Because people only text me during games when what happens?”

Something bad.

“Something bad. Nobody ever sends me a text message saying, ‘Wow, did you see that grand slam?’ They’re always like, ‘How the f--- did we give that up?’ ‘Why did we throw that pitch?’ ‘What are we swinging at?’ So I made a rule a couple years ago. No one can text me unless it’s about roster moves that we have to prep.”

It’s worth noting here that he has four sons ranging in age from 13 to 17. But they know the rule, and they follow it, as does everyone else.

“You have no control over it,” he says. “It matters so much. It's this sick combination of those two things coalescing, and you're responsible for all of it. So you feel that pressure, too, when you're at home and you're losing by, like, eight runs. You’re chewing on it. So I try to find places that work and ways that work and I will stick with those until they don’t work and then I’ll abandon them. So it’s a whole host of things, but it’s always in my mind. It’s in my mind 24/7. ‘What am I doing? I didn’t do this yesterday. We won. I can’t do this. I gotta do that.’”

Most general managers exhibit some level of unhinged behavior; the role does not attract the truly well-adjusted. But this degree of neurosis has to be unusual among his peers.

“There’s only a handful that would admit it,” he muses. “You’re never going to get the real answer. I’m letting you behind the curtain a little bit. This isn’t something I’m proud of.” Finally he decides that he likely ranks “in the bottom five.”

Hazen is a smart guy. He went to Princeton. Surely he could get a job that doesn’t give him this many ulcers. But he insists he’s having fun—just not for the nine innings the game is played. “The rest of it’s great,” he says.

Has he always been like this?

“Like, a freak?

Yeah, kind of.

“Yeah. It’s not good.”

He shakes his head sadly and walks off—hopefully to wash his socks.