Swing Changes Could Elevate Yankees’ Anthony Volpe, Other MLB Hitters

In the second half of last season, I spoke to St. Louis Cardinals manager Oliver Marmol about rookie outfielder Jordan Walker, who was hitting too many ground balls, especially for someone listed at 6' 6" and 250 pounds. We both agreed Walker needed to make mechanical changes to his odd swing.

“Not now,” Marmol said. “Those things are better for the offseason.”

“Like Nolan Gorman?” I said.

“Like Nolan Gorman,” he said, nodding.

As a rookie with the Cardinals in 2022, Gorman could not hit a high fastball in the zone (.097). Every team knew it. He worked in the offseason on swing changes to take a bit of the loop out of his swing. He improved to .204 against high fastballs in the zone. A 27-homer hitter, Gorman improved his slugging from .420 to .478.

Swing changes can sound this time of year like another version of “best shape of my life” stories. They make for good spring training narratives. But they can turn careers around, as they have done for Josh Donaldson, José Bautista, Justin Turner, J.D. Martinez, Mookie Betts, Brandon Crawford, Aaron Judge and so many others.

I was thinking about swing changes this week as Cody Bellinger finally re-signed with the Chicago Cubs. Bellinger settled for a three-year deal (with opt outs) because the industry was not convinced his bounceback season last year was real enough for a longer commitment.

I’m convinced it was real. And it’s because of a swing change that started in the offseason. Bellinger may not be the slugger he was in 2019, but he made a real effort to get the barrel to the baseball on a better path. He became the best two-strike hitter in baseball this side of Luis Arráez. (So please don’t tell me about his exit velocity; if you watched him play a little bit last year, you saw a major effort to simply put the ball in play with two strikes and with runners on.)

Bellinger moved his hands slightly higher to stay above the ball, started his hands and feet a bit earlier to be on time, loaded more on his back hip and entered the hitting zone with the barrel a bit flatter. It took an entire offseason of work.

So, who will be this year’s Bellinger? Who is going to be rewarded for the hard work of dialing in a swing change in the offseason? Who is more than a cute spring training story but a breakout star? Here are four candidates:

Jeremy Peña, Houston Astros

I was always perplexed at Peña’s setup and swing. He would dip the bat behind him as the pitcher gathered to throw, as if dipping a flag standard, a quirk that often would create timing problems with his load. It often appeared that he was “reaching” for off-speed pitches rather than staying back.

Like a lot of Houston hitters, Peña never gets off the fastball. His huge 2022 postseason was built mostly on fastballs (.462 with an .808 slug) and not secondary pitches (.250, .500). That’s the story of his career: crush fastballs (.294, .450), survive against all else (.220, .354).

Last year his setup and swing caught up to him. Peña was a ground-ball-hitting nightmare. He hit just 10 home runs, none after July 5. He finished with the 10th highest ground ball rate (54.4%) and with the ninth biggest ground ball increase (+6.7%). He was so lost by the postseason that he couldn’t hit a fastball (.182).

Always known as a hard worker, Peña immediately went under the hood to diagnose the problem. He started with his setup. No more dropping the bat. Peña created a new trigger mechanism in which he starts with the bat on his back shoulder, then raises to the proper load angle as the pitcher shows his front hip. In early video, it appears that Peña is in a ready position earlier and with more balance.

When I first saw video this spring of Peña, the first guy that came to mind was Manny Machado. Similar setup: open stance off the plate, bat resting on shoulder before that front hip of the pitcher starts to turn homeward. Simple. Balanced. Consistent timing.

Here’s a look at Peña last year with that drooping of the bat as the pitcher kicks his leg, and next to it is Machado at the same point as quietly coiled as a cat just waiting to pounce.

Anthony Volpe, New York Yankees

The Yankees in recent years pushed an organizational hitting philosophy of getting the ball in the air. And why not? The four teams that hit the most flyballs last year? The Los Angeles Dodgers, Astros, Texas Rangers and Atlanta Braves, four very good teams.

But not all hitters are built for launching. Volpe is one of them. Volpe hit with such an uphill swing path last season that he was one of the worst hitters in baseball against high fastballs (not including cutters).

Player | Average |

|---|---|

J.D. Davis, Giants | .068 |

Anthony Volpe, Yankees | .105 |

Corbin Carroll, Diamondbacks | .111 |

James Outman, Dodgers |

Volpe did adjust his setup (not his swing) during the season, and he did manage to pop 21 homers, even if six of them were fastballs he carved into the short porch at Yankee Stadium. But Volpe hit .209, the worst by a qualified Yankee in 55 years. He also struck out 167 times. No Yankee ever hit so low and struck out so often—and it’s one of only 18 such seasons by any player.

There was just no way he was going to become a consistent hitter without a better swing path. He also needed to become “quieter” with his head. Volpe would start tall, sink into his knees and then rise again as his shoulders tilted. The excess movement is one reason why he was such a poor breaking ball hitter: .147, fourth worst in MLB.

To his credit, he recognized it and went to work after the season and has been showing a “flatter” swing this spring—a catchall term that basically means the barrel of his bat is entering the hitting zone more even with the ball path rather than under it.

If he needs a swing role model, it’s Nico Hoerner of the Cubs. With Volpe’s speed, if he puts more balls in play, he becomes closer to the 97 OPS+ Hoerner posted than the 81 Volpe had last year. Volpe should not try to be a 30-home run hitter—not yet. He should be Hoerner, a master at getting on top of high fastballs. Last year Hoerner hit .308 against high heaters, 10th best in MLB. The league average is just .211.

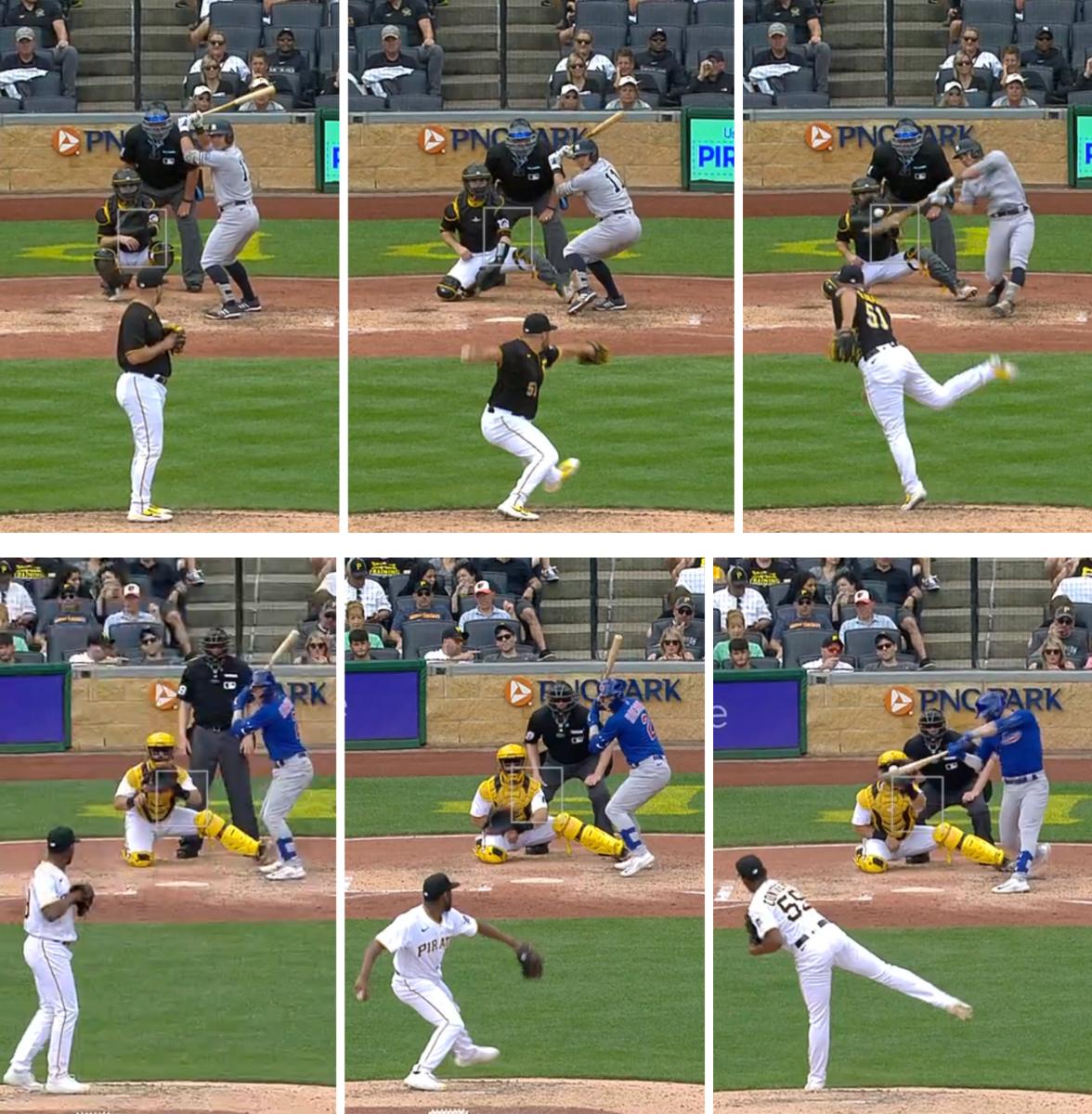

Here is a comparison between Volpe and Hoerner as they swing at high fastballs at three key stages: setup, load and swing path.

Key takeaways:

- Head position: Volpe’s head moves too much. It’s up, then down and then tilted because of the extreme angle of his shoulders. Hoerner’s head is quiet. He gets to the high fastball with the classic position of chin down the ball.

- Hands: Volpe likes to hit with his hands away from him. Hoerner keeps them tighter in a more connected position, which leads to a shorter swing.

- Barrel position: Volpe’s barrel enters the hitting zone under the ball. With the velocity in the game today, that’s a huge red flag. Hitting is like riding a bike: If you work uphill, you’re going to move slower. Hoerner takes his barrel to the ball above the pitch.

By the way, the result of those swings: swinging strikeout by Volpe; home run for Hoerner.

Joey Wiemer, Milwaukee Brewers

I like to watch Wiemer hit because he’s an athletic, fast mover in the manner of Hunter Pence, which is a reminder that no one should be teaching a cookie-cutter approach to swinging the bat. It’s similar to the golf swing: As long as you get to the impact point on time and on balance, how you get there can be highly personal.

But Wiemer pushed the limits of pre-impact movements too far. He used three different timing mechanics, including dipping and pumping his bat before his swing even started. (Former Brewer Keston Hiura suffered from similar complications.)

Wiemer’s swing seemed crafted to always gain ground on the fastball, which is not a bad idea in today’s high-velocity game. But in fact, the movements created so much length that he hit just .209 against pitches 95+ mph.

Worse, the swing made him extremely vulnerable to breaking pitches. Great breaking ball hitters have quiet hands and good balance. Wiemer had neither because of his excess movement. Boy, did pitchers notice:

Player | Pct. | Avg. |

|---|---|---|

Joey Wiemer, Brewers | 43.0% | .160 |

Teoscar Hernández, Mariners | 41.2% | .212 |

Harold Ramírez, Rays | 39.8% | .310 |

Let’s take a look at the sequencing of that busy swing on a left-handed breaking ball:

Key takeaways:

- Barrel is high above his head.

- Barrel is low behind his back (timing mechanism #1).

- Barrel is dipped in front of him as part of a pumping action (timing mechanism #2).

- Toe tap (timing mechanism #3) and extremely low hands.

- Top hand is turning over early (and about to leave the handle) because he has committed too soon—what hitters call “running out of barrel” because the barrel is through the hitting zone before the ball arrives.

- Classic finish of early commitment: top hand off the bat, sinking deeply into legs to try to buy more time and off-balance posture.

There’s a saying among pitchers that despite all the laser-guided pitch-tracking technology, nothing measures the quality of your stuff like the hitter’s bat. The inverse of that aphorism is nothing will reveal a hitter’s holes like the way pitchers attack him. It was clear to Wiemer that pitchers told him he was vulnerable to spin.

To put more balls in play against spin, he needed to quiet his hands and improve his balance. When I saw his rebuilt swing this spring training, one hitter immediately came to mind:

Judge has made two major swing changes in his career. After hitting .179 as a rookie in 2016, he tweaked his swing to load more on his back hip. He promptly hit 52 homers and was MVP runner-up.

After a fourth-place MVP finish in 2021, Judge changed the position of his hands at setup so that, as he likes to say, they could always “see the pitcher.” In other words, they start in front of him. That posture corrected a slight over-rotation problem in his load. His hands used to get stuck behind his head sometimes (no longer able to “see the pitcher”). The adjustment with his hands made his swing path shorter to the baseball and closed a hole he had on velocity in. He promptly hit 62 home runs, including 26 to the pull side—10 more than he ever hit in a season.

Like Judge, Wiemer sets his hands so they can “see the pitcher.” More importantly, he keeps his hands quiet as he maintains barrel integrity throughout the load phase. His hands never get stuck behind him. They also don’t get so low.

The swing is much more balanced and simpler. He is better able to leverage his strength and quick-twitch movements against a wide range of velocity.

Jordan Walker, St. Louis Cardinals

Important fact: Walker is only 21 years old. Last season he slashed .276/.342/.445 with a 114 OPS+ even with mechanical issues. He is going to be a monster hitter. I remember when Mark McGwire told me when he looked back on his league-leading 49 homers and .618 slug as a rookie, “I have no idea how I did it. I had no clue what I was doing.”

The way Walker swung the bat last year with a weak lower half, he could not drive low pitches and he could not use the opposite field much at all. The typical MLB hitter hits 17 points worse on pitches in the lower third of the zone than those above it. Walker’s delta was a staggering 118 points:

Zone | Avg. | SLG |

|---|---|---|

Middle and top third | .385 | .680 |

Bottom third | .267 | .370 |

And Walker clearly likes to hit the ball out front, which leads to great pull-side power but also too many rollover grounders.

Direction | H | Avg. | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|

Pull | 55 | .440 | .832 |

Middle | 42 | .362 | .431 |

Opposite | 19 | .253 | .440 |

Walker needs to hit more balls in the air. He needs to use the gaps more. Even more importantly, he needs a better base. He needs to load on his back hip—the way Judge figured out after his rookie season—and needs to keep his back side from collapsing to drive through the baseball, not over it.

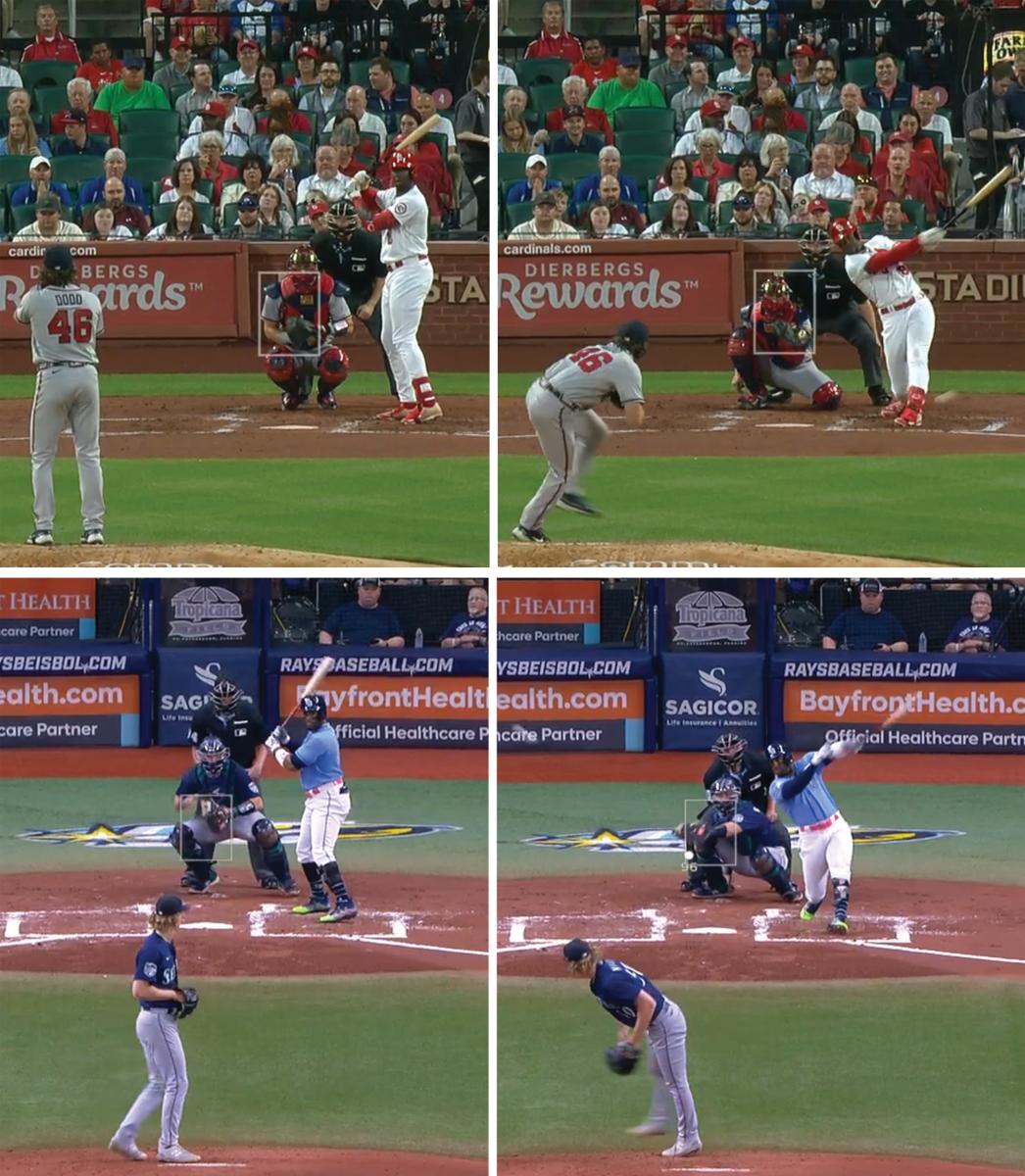

If you need a model for staying through the baseball with a strong lower half, there’s no better one than Yandy Díaz, who hit a staggering .397 last year on low strikes. Here are setups and swings from Walker and Díaz last year on the same pitches, fastballs low and away in the strike zone:

Key takeaways:

- Setup: extremely similar in terms of where they set their feet and hold their hands.

- Swing: Walker’s back knee drops and turns inward toward his front leg—away from the ball. The weakness of his lower half is evident by the way his back foot and ankle “roll.”

Díaz has driven his knee toward the ball, and you can see his heel lift in a “kickstand” posture with his foot as his weight has transferred through the ball.

On these swings, Walker topped a weak grounder to third (the ball is near his front foot) and Díaz smashed a line single to right.

One more point: Without a strong lower half, Walker finished with a more severe torso angle than does Díaz:

Last season Walker hit 47% ground balls, which is above the major league average of 45%. Look for him to cut that rate to no more than 43%, which would put him in the company of hitters such as Hernández and Rafael Devers and bring a 30+ homer season into play.