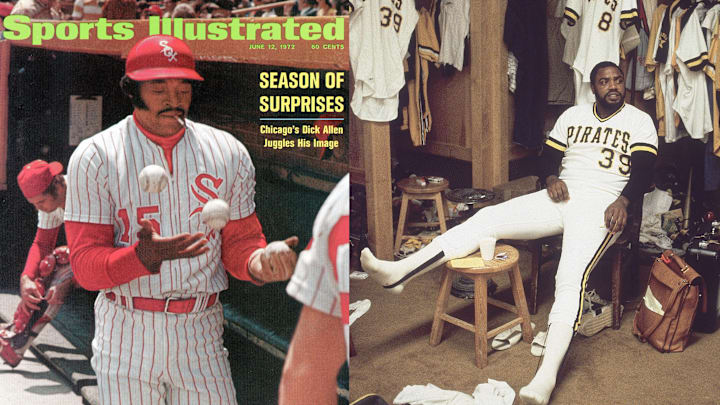

Though Long Overdue, Dick Allen and Dave Parker Fittingly Enter Hall of Fame Together

Forty-seven years after he played his last game and two years and one day after he drew his last breath, Dick Allen is a Hall of Famer. Thirty-three years after his last game and 12 years after a tremor in his right hand eventually led to a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, Dave Parker is a Hall of Famer.

Allen and Parker have a shared history, so it is right that they be enshrined together next summer. Both were among the best hitters of their generations who hit the ball so hard they were imposing threats in the batter’s box. Both became the highest paid players in baseball (Allen in 1973, Parker six years later). Both were managed at the top of their game by Chuck Tanner, a man who allowed them to flourish by treating them with respect when others did not. Both suffered open racial prejudices. Both endured waits for the Hall not much different than their careers: long and difficult.

On Sunday, the Classic Era Committee corrected long oversights by recognizing that Allen and Parker have been underappreciated all these years, especially during their careers. Parker was named on 14 of the committee's 16 ballots and Allen by 13 of them—clear favorites on a solid ballot. Of the maximum 48 votes, Parker, Allen and third-place finisher Tommy John (seven votes, five short of election) accounted for 71% of the most possible votes.

Allen had fallen one vote short twice before. His credentials included the highest OPS+ (156) of any hitter not in the Hall and not connected to PEDs (min. 1700 games). Over his first 11 full seasons (1964 to ‘74), he led the majors in OPS+ (165). The players behind him? Willie Mays, Frank Robinson and Henry Aaron. He swung a 42-ounce bat with viciousness.

Allen spent 15 years on the writers’ ballot and never pulled as much as 20% support. What hurt Allen was a reputation for disrupting clubhouses. In one six-year period, from 1969 to ‘75, Allen was traded five times. The sabermetrician Bill James wrote 30 years ago, “He did more than anybody else to keep his team from winning, and if that’s a Hall of Famer, I’m a lug nut.” What most people missed or chose to ignore was the turmoil and racism Allen faced as one of the first black stars of the Phillies.

In 1963 when Allen was 21, the Phillies assigned him to Triple A in Arkansas. Allen, who grew up in Western Pennsylvania, later wrote that he begged the Phillies not to send him there. He had never been in the South, and he knew Little Rock was a cauldron of racial unease. When he arrived for the opener on April 17, 1963, Allen was greeted by white supremacists picketing the ballpark. The Associated Press reported, “The game was the first desegregated baseball game at Little Rock and several hundred Negroes were among the crowd that watched Gov. Orval E. Faubus throw out the first ball.” Faubus was the same man who six years earlier refused to comply with Brown vs. Board of Education and ordered the Arkansas National Guard to bar black students from attending Little Rock Central High.

When Allen joined the Phillies later that same year, he found more racial animus in his home ballpark and state. The Phillies were the last National League team to integrate. They fielded all-white teams until 1957, exactly a decade after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, when they gave shortstop John Kennedy a brief trial. In 1965, Allen and white teammate Frank Thomas engaged in a clubhouse fistfight. The Phillies released Thomas, but many fans blamed Allen.

Over the years Allen weathered so much abuse from fans, including objects they threw at him, that he took to wearing a helmet when in the field.

Like Allen, Parker had to play through verbal abuse and flying objects, even in his home ballpark. The anger directed at him grew in Jan. 1979, coming off a second straight batting title and the MVP award, Parker signed a five-year contract that paid him just under $1 million per year, making him the highest paid player in baseball. (Ten months later, Nolan Ryan would break the $1 million barrier when he signed as a free agent with the Astros.)

It was early in the free-agent era, a time of rising salaries and concurrent rising resentment from fans. Parker became a target because as great as he was—“He’s the best player in the world,” Tanner said—nobody is great all the time. Pittsburgh fans booed Parker. (The same treatment was evident for Mike Schmidt in Philadelphia the previous season.) In 1979, Parker’s car was vandalized in the Three Rivers Stadium parking lot. Three times somebody broke into his house. People sent him racist mail filled with epithets and telling him to “go back to Black Africa.” Parker kept those letters and postcards.

“It gives me inspiration,” he explained then, “When I’m tired, I look at them.”

The next year a fan at Three Rivers Stadium threw a battery at him while he was playing right field. It came so close to his head he heard it whoosh by.

“You pay your money, you’ve got a right to do something, verbally,” he said after the incident. “But this … it’s getting unbearable. If this keeps going, I can’t continue my career.”

Meanwhile, Parker had demons off the field that would not come to light until the infamous Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985. Parker testified that he used cocaine from 1976 to ‘82, sometimes facilitating access for his supplier to the Pirates’ clubhouse and airplane. By then, Parker’s great skills were eroding. Parker averaged 4.6 WAR over his first seven years, but fell to 0.7 per year over the next three after his MVP season.

“I stopped using in the late part of ’82,” Parker testified. “I felt my game was slipping and I feel it played some part in it.”

Parker played another nine years. While he did not return to his elite late-70s prowess, in that second stage to his career, he made three All-Star teams, finished in the top five MVP voting twice, won his first RBI title and became a clubhouse leader with the Reds, A’s (where he won a World Series in 1989), Brewers, Angels and, briefly, Blue Jays. Teams kept signing Parker because he could still hit and he knew how to keep a team loose. Parker was a renowned wit who spoke his mind, such as the time when someone asked him about the Pirates possibly facing Montreal Expos lefthander Bill Lee.

“Bill Lee pitching against us is like walking into a lion’s den with a hamburger suit on,” he roared.

Allen and Parker dealt with the hostility directed at them in different ways. Allen was more of a loner who stewed after slights. He left the White Sox with two weeks left in the 1974 season because of a feud with a teammate. Though Allen won the home run title that year, Chicago sold his contract to the Braves. He refused to report. He retired at age 33. The Phillies talked him out of retirement. He played three more seasons, largely as a part time player. Parker was gregarious and outspoken, often the loudest man in the room and with a smile on his face.

Allen and Parker waited too long to get their due, especially with Allen being honored posthumously and Parker battling Parkinson’s. But it just seems right that when finally it did come, they are part of the same class. With this honor, those that never saw them play especially need to discover their stories. There is so much Allen and Parker share in how well they played baseball. And how much they endured.

More MLB on Sports Illustrated

feed