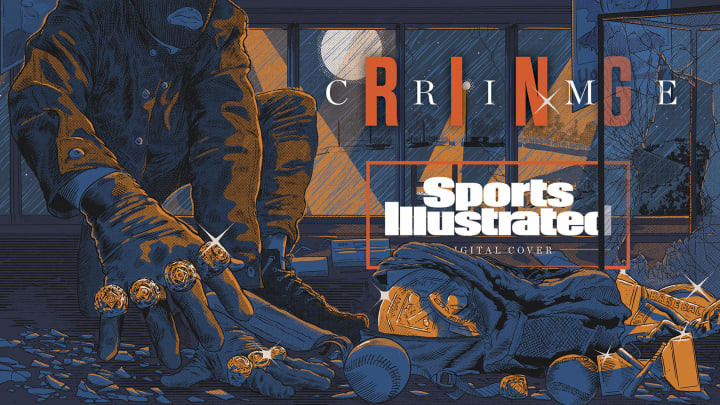

Crime Ring: The Story of the Sports World’s Most Infamous Thief

It sat there, upright and pristine and crisp in a display case, looking like a sacred garment attire worn by royalty.

Which, in a sense, it was. The 1906 baseball season accounted for 22 of the 373 wins in the Hall of Fame career of Christy Mathewson. And, as he mowed down batter after batter for the New York Giants, he was clad in this thick, off-white, woolen jersey.

In large block letters embroidered across the chest, the uniform top bore the words world’s champions, a reference to the team’s triumph the previous autumn. The 6' 1", 195-pound Mathewson had cut the right sleeve off at the elbow, so he could pitch without loose fabric interfering with his motion.

In the summer of 1999, that game-worn jersey, nearing 100 years in age, was preserved in plexiglass at Keystone Junior College in La Plume, a crumb on the map in northeast Pennsylvania. Mathewson, raised in nearby Factoryville, had attended Keystone in 1898, two years before making his major league debut.

Each summer, the highlights of Keystone’s Mathewson collection—baseballs he’d thrown with force and accuracy, books by and about him, his military clothing from World War I—all came tumbling out of mothballs for the annual Christy Mathewson Day, a local celebration held in conjunction with the pitcher’s Aug. 12 birthday.

On the night of Aug. 13, 1999, a local actor delivered a Mathewson-based monologue inside the library. As the rest of the audience sat rapt, listening to Dead Ball era tales and accounts of Big Six’s battles against Ty Cobb, one man in the crowd was distracted by the crisp vintage jersey.

Tommy Trotta was a devoted baseball fan. He was also a devoted thief. Though only 24 at the time, he had long since settled into a life of crime. Trotta was never violent. Only on rare occasions were his heists truly lucrative. But burglary was his full-time job. And, more critically, a kind of compulsion.

He reveled in preparing for heists, accumulating and poring over videos of his targets the way batters watch film of opposing pitchers. He’d become an expert in picking locks, outwitting security systems and fashioning escape routes. He’d survived close encounters. With cops. With dogs. With the kind of bad luck that could undermine even the best-laid plans. Both adventures and misadventures imbued him with a surge of joy and vitality.

That evening, Trotta and a friend, also a baseball fan, had driven up from Trotta’s home in Scranton, less than 20 miles away. He came with no specific designs of thievery. But that Christy Mathewson jersey? It was the equivalent of a hanging curveball.

Sitting in the audience, Trotta swiveled his gaze. He noticed that, in addition to the jersey, there were two of Mathewson’s signed playing contracts resting inside the case. He recalls saying to himself, It can’t be this f---ing easy.

In the early morning of Aug. 14, hours after the festivities had ended, Trotta returned to Keystone. Only this time, he came with a different friend, dressed not as a baseball fan but instead wearing a mask and black clothes, armed with a crowbar in one hand, a bag in the other.

At around 3 a.m., he slithered through the door. Trotta thought he saw the security guard. Already bathed in sweat, he debated with himself whether he could outrun the guard. But as he inched closer, he realized it was a night cleaner, operating a vacuum. Not only was a cleaner less menacing than a guard, but also the purring and whirring of the vacuum would muffle the soundtrack of his breaking and entering.

Trotta prepared to smash the glass, but, realizing the case was unlocked, he simply “shimmied it loose.” Baseballs dribbled onto the floor. Ignoring them, he snatched the jersey and the two contracts. Then, he used a walkie-talkie to tell his accomplice it was time to pick him up.

On the ride back to Scranton, Trotta’s co-conspirator, also a baseball fan, explained that the contracts were signed by John McGraw, the Giants’ esteemed manager. The wingman speculated that the documents could be worth $500,000 each. You’ve got a million bucks right there, he hissed.

Trotta, though, had no interest trading on the seamy sports memorabilia market. He was more interested in the jersey. “It was like a thick Spalding wool thing,” he recalls. “I would wear it periodically, just put it on,” he says, even as news outlets like CNN and The New York Times reported on the theft. “Like it was a treat.” It draped over his 5' 8" physique like awkward scaffolding, but he didn’t care.

Where’s that jersey now? He’s not quite sure. Maybe in a friend’s garage. The contracts? No idea.

Trotta would continue his string of cat burglaries, stealthily lifting everything from jewelry to rugs to art to Amish weather vanes over the years. But the Mathewson heist was a kind of gateway drug. Trotta got hooked on stealing sports memorabilia. Rings, belts, trophies, plaques.

For the next two decades, again and again, throughout the United States, sports museums and libraries reported break-ins and thefts. The museums usually offered a reward for the return of the items. They often also offered a theory of the crime. “Inside job” was the fallback. And there was conjecture that there were multiple copycat thieves.

But now, after decades of missing treasures, we know: There was one man responsible for virtually it all.

Today, Tommy Trotta, now 49, is heavy with shame and remorse. He can also resemble a former athlete recounting “good years” and lucrative scores, and also “screwy screw-ups” and stinging misses. Confronted with the suggestion that he’s probably the biggest sports memorabilia thief in history, he pauses, running a hand over his bald head.

“Ya think? I never really saw it that way. Maybe you’re right.”

When Trotta was finally arrested in 2019, he came clean. Asked by a judge how he pleaded to various charges, Trotta responded, “Very guilty.” He confessed and then cooperated with state and federal investigators, leading to the 2023 indictments against eight alleged co-conspirators. First in the Luzerne (Pa.) county jail and then, upon his release last summer, in Scranton, Trotta spoke to 60 Minutes and Sports Illustrated, giving up the game, as it were, and telling his whole story.

How do you become a career thief? It’s not dissimilar from the way you become a career athlete. Though Trotta was always a decent jock—and even had an aunt who played baseball for the Rockford Peaches—he figured he would need to be fast. So he spent mornings at a local track and, he says, shaved his time in the 400 to a respectable 57 seconds. And he watched a lot of film.

As with sports, it helps—if that’s the word—to have a parent experienced in the field. When Tommy Trotta Jr. was born in 1975, his father, a Vietnam veteran, was serving on the Passaic, N.J., police force. Not for long. When Tommy Jr. was 5, Tommy Sr. was hired by local mobsters to set fire to a local gay bar. He got caught and spent time in prison. When he was released, the family moved to greater Scranton.

Marooned in northeastern Pennsylvania, Tommy Jr. noticed that his father had emerged from prison harder, not softer. “He always had something cooking,” Tommy recalls. He would go to Gettysburg and enlist Tommy Jr. as a late-night lookout while he would walk around battlefields and enter historic homes with a metal detector. Another time he paid Tommy Jr. to count how often a car drove past our house. “I was like, ‘Forty times, Dad.’ He was like, ‘Oh, s---, Really?’ I later learned it was the FBI.”

Tommy also got an introduction to crime from his older sister’s boyfriend. “I was doing burglaries,” Trotta says, “when I still believed in Santa Claus.” He started as a lookout. But Tommy reckons he was 12 or 13 when he joined a group of older kids to break into the local True Value hardware store. They stole power tools. And then used them to open the safe. He says his share of the loot was $1,400. “And it felt,” he says, “like a million bucks.”

Eventually, Trotta and his ragtag crew of buddies and neighborhood toughs became interested in the tools of the trade: crowbars and blow torches and sledgehammers for ransacking equipment. Breaking into vending machines and ATMs somehow seemed less morally culpable than breaking into someone’s home and taking personal items.

They also devised a tool to break into the golf ball dispensers arrayed on driving ranges. Late one night, Tommy Sr., who died in April 2023, walked downstairs to find Tommy Jr., then 15 or so, on the floor with friends divvying up money and golf balls. Tommy recalls, “He said, ‘Today, it’s golf balls. Tomorrow it’s something else. And it’s never gonna end.’ But he didn’t necessarily say, ‘Don’t do these things.’ ”

After the Mathewson jersey theft, Trotta spent the next few years with his crew rampaging locally, often reselling the stolen merchandise online. He made a decent living, reckoning that it beat a real job. And the game of it all—the preparation, the risk, the outwitting of police—was as much a motivation as the money.

Then, the week before Thanksgiving in 2005, Trotta upped the stakes. Scranton’s Everhart Museum, the kind of small omnibus arts center that hosts Hot Chocolate Night and offers science programming for children, also boasts a gallery of significant American artwork. Trotta first visited the museum on school field trips. On return visits as an adult, he took his infant niece and nephew. While they stared at art and objects, he held out a video camera, casing the joint. “Everyone thought I was an uncle [videoing] cute kids,” he says. “I didn’t look like no art thief, I guess.”

Trotta studied the window and alarm system and the movements of the guards. He also bought a copy of Davenport’s Art Reference & Price Guide, an index to art prices. Flipping through it one day, he noticed paintings by the abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock. “I didn’t know nothing about Pollock at the time,” he says. “I’m like, Holy s---, there’s one of them down at the Everhart.”

After midnight on Friday, Nov. 18, Trotta and his friends were at a Scranton sports bar, Whistles Pub, when a brawl erupted. Trotta and his crew weren’t involved, but they watched as half of Scranton’s police force came to break up the fight. Inspiration struck: With so much local enforcement restoring peace at Whistles, it would be an ideal time to deploy the museum plan.

It was after 2 a.m. when Trotta used a ladder to shatter a glass door in the back of the building. The alarm system was triggered, as Trotta suspected it would be. But he caught a break. The surveillance cameras weren’t operational. First, he grabbed Springs Winter, a 40-by-32-inch oil canvas Pollock had painted in 1949, on loan to the museum from a private collector, hanging on a wall. Then Trotta took La Grande Passion, a 40-by-40-inch silkscreen that pop artist Andy Warhol created in 1984 for a cognac ad campaign.

By the time the police arrived four minutes after the alarm sounded, Trotta was gone. The Warhol was estimated to have an auction value of $15,000. As for the Pollock, a similar painting had sold the year before at auction for $11.6 million.

There was one fundamental problem: What now? With an eight-figure painting in their possession, Trotta and his crew realized there was no actual market. This was the Mathewson jersey all over again. Except the purloined objects in question were worth millions to collectors. “[The burglary] got all this attention,” he says. “I realized if we tried to sell this thing, we’d be busted right away.”

Chastened by the art heist that, while successful, didn’t make him any wealthier, Trotta focused on sports memorabilia. As with the paintings, there was a steep risk that came with trying to sell stolen goods on the $25 billion sports memorabilia market. So instead of trying to find buyers, Trotta seized on an idea whereby he could lift valuable sports artifacts, get some money, and then rest assured the objects would disappear.

Specifically, a member of Trotta’s crew was adept in welding and metalworks. The gang would take stolen items back to a rural garage. There, they would remove jewels and then melt the contents until only precious metal remained.

Then Tommy and crew headed to the Diamond District in Manhattan where, he says, a Russian dealer paid them cash for gems and precious metals, no questions asked. “We would come in with stuff. He’d then weigh the gold or silver,” says Trotta. “He’d tell us how much. He’d go to this machine that spat out the bills. We’d ask for a little extra for bridge tolls and gas and stuff. Then we’d go home.”

In 2011, Trotta and crew drove to the Scranton Country Club. There, they made off with 11 trophies, including four awarded to Art Wall, Jr., a local golfer who won the Masters in 1959. Trotta says that it was also around this time that he began making a series of “research trips” to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., two hours north of Scranton. He estimates that he had more than 20 hours of reconnaissance footage. Trotta had learned of the Hickok Belt held there, an award that, between 1950 and ’76, was conferred on the Athlete of the Year in the U.S. The belt—with a buckle of solid gold and studded with diamonds and jewels—was valued at more than $200,000.

The first Hickok Belt was presented to the Yankees’ Phil Rizzuto, whose family later donated it to the Baseball Hall of Fame. But while finalizing a plan, Trotta learned that, before making their donation, the family had removed the jewels from the belt and embedded fake gems in their place. “That,” Trotta says flatly, “is the only reason I didn’t do Cooperstown.”

Undeterred, Trotta began studying other Hickok Belt winners. Golfer Ben Hogan won it in 1953, the same year he won three majors. After Hogan died in ’97, his estate donated a replica of the belt to the U.S. Golf Association Museum in Liberty Corner, N.J., 100 miles from Scranton. In early 2012, Trotta began making trips to the museum. He dressed as a tourist and filmed at every opportunity. He and his accomplices waited for a rainy night, which they figured would buy them some time when police responded to alarms.

On May 15, 2012, they rented a Lincoln Continental. (“Fancy cars help,” Trotta explains. “Piece of s--- cars get pulled over.”) It was around his customary “go time” of 2 a.m. on May 16 when the driver exited off I-80 and dropped Trotta on a side road. He ran through woods and fields and approached the stately venue through its security office. Using an axe and pick, he punched his way in through a window with blunt force but cut his hand.

Bleeding, he headed to the Ben Hogan Room, where the golfer’s memorabilia was on display. After smashing the case, Trotta made off with the Hickok Belt and dashed to another part of the museum to pick up—after much exertion, swinging his axe through a thick glass case—a gold U.S. Amateur trophy. He threw it in a bag with the belt and jumped out a window.

As he sprinted through a field, he called the getaway driver on a burner phone. The driver picked up Trotta, who promptly tossed the phone out the window. According to public records, police responded to an activated alarm that went off at 2:29 a.m. By the time they got there, Trotta was riding shotgun in the Lincoln.

That same year, Trotta knocked off the Harness Racing Museum & Hall of Fame in Goshen, N.Y., making off with 14 trophies valued at more than $300,000. A year after that, he ventured to the National Racing Museum & Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., where he took five items, including the 1903 Belmont Stakes trophy. Again and again they would take the stolen items to the garage, melt them down, accumulate the gold and silver and then exchange the metals for cash in Manhattan.

How does a man who, at the time had a wife and family, duck off on these excursions? “I would concoct a lot of stories,” Trotta recalls. “I would mostly say, A lot of my buddies have contracting businesses. I’m working for this one, I’m doin’ this job in North Dakota. It’s like [I was] a professional liar. Which is horrible.”

In 2014, Trotta undertook perhaps his most high-profile target: the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center near Montclair, N.J. After waiting weeks for a rainy forecast, finally, on Tuesday, Oct. 7, he and an accomplice made the drive to northern Jersey.

Shortly after 2 a.m., Trotta ran across a baseball field that abuts the Berra museum. Using a ladder, he climbed into a skybox above home plate. He then shattered a museum window, entered and headed to the trophy cases.

Berra, of course, won more World Series rings than any other player in major league history. But reckoning that it was tacky to wear more than one at a time, he kept nine of the 10 under glass. Nearby were two of his American League MVP plaques.

Trotta knew that, often, once glass display cases splinter, they’re easy to cut through. “But now the Yogi Berra cases were somethin’ special—a kind of bulletproof glass that was never gonna shatter. So I had the grinder with a rescue blade. And I actually cut the cases open, reached and grabbed the rings, went to the other case, pyramid cut them to get the two MVP plaques out also.”

The museum alarms sounded. But by the time police responded, navigating the slick roads, Trotta was gone. The total haul? Nine World Series rings, seven additional rings and two MVP plaques. Conservatively, it was valued at more than $1 million.

What did Trotta do with the loot? “Cut ’em, melted ’em. And it bothers me, even sayin’ it right now to you…. I thought about him. I used to go to Yankees games when I was younger. I don’t think they want me goin’ to the games now.”

When the crew went to Manhattan, they exchanged the melted gold and jewels for $12,500. Pressed that selling $1 million in memorabilia for $12,500—barely pennies on the dollar— doesn’t exactly sound like a business model worthy of Ocean’s Eleven, Trotta pushes back. “It was money, it was cash,” he says. “I didn’t look at it as what it was worth. I looked at it as $12,000 is good money for one night of work.”

Other outings were less successful. In November 2015, Trotta rode shotgun as an accomplice drove a rental car, headed toward the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, N.Y., blasting AC/DC’s “Thunderstruck” as psych-up music.

His accomplice, it turned out, had forgotten to bring a stepladder. So while Trotta had designs of entering through the roof, he instead needed to smash his way in with an axe (cutting his hand in the process). Once inside, he made his way past Mike Tyson’s old heavy bag and an array of robes and signed gloves. He headed to a glass case and snatched six title belts that belonged to former welterweight champ Carmen Basilio and middleweight Tony Zale, each glittering with gold and valuable jewels.

Back in Scranton, they wore the boxing belts and pretended to hit each other with them, WWE-style. Giddiness turned to disappointment when they discovered the composition of their haul. Says Trotta: “We have these little acid tests. We’re testing it, scratching it. Every f---ing belt’s fake. They told [the boxers] it was gold, but it wasn’t.”

Distress deepened when Trotta stripped the gems off the belts and took the jewels to his fence in the Diamond District. The dealer studied the gems and shook his head. “They’re synthetic. Garbage. Where’d you get these belts, Kmart?”

Says Trotta: “I felt bad cause I wouldn’t even have taken the things if I knew we weren’t gonna get any money. I would’ve mailed them things back up to them.”

But he didn’t. He turned to stealing another Hickok Belt, this one awarded to Berra’s former Yankees teammate Roger Maris. For months, Trotta made scouting trips to North Dakota, where the Roger Maris Museum is housed in the West Acres Mall. Trotta focused not just on Maris’s Hickok Belt from 1961, but also his ’60 American League MVP Award. There was one significant impediment. “I knew,” Trotta says, “there were security guards at the mall.”

Trotta’s solution was to ditch his usual ninja getup and instead dress as a security guard, “with a badge and everything.” In July 2016, on his third trip to Fargo, Trotta made his play. He broke into the display case, swiped the items and left without detection.

Trotta was never armed, never carried a knife, never took a hostage, never so much as threw a punch. He was a nonviolent criminal. But he was a criminal nonetheless. And the crimes were not victimless.

Lindsay Berra has worked as an ESPN journalist, an entrepreneur and a filmmaker. But her ultimate life’s labor is preserving the legacy of her beloved grandfather. In 2014, she was working on a project for Major League Baseball when she received the call from the director of the Yogi Berra Museum. “There was disbelief that someone would break into a place like a museum,” says Berra. “I mean, you see it on the Thomas Crown Affair; you don’t expect it’s going to happen at the little Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center.”

She informed her grandfather, who was 89 at the time. He had two immediate responses. He minimized the trauma with a typically philosophical take. “Well, I know I won those things,” he said. His bigger concern: Could the remnants of the burglary be cleaned up in time before the next group of school kids visited the museum?

By her own admission, Lindsay had a harder time taking the high road. “I was a thorn in the side of the Passaic County Sheriff’s Department for a long time,” she says. “I was calling the detective probably once a week. They kept telling me there’s nothing new, nothing new.”

As she began investigating on her own, she read about the other sports museums and Halls of Fame that had been violated. “I immediately thought, Oh my goodness, it has to be the same people—otherwise it’s just too much of a coincidence,” she says.

When she led tours at her grandfather’s museum, inevitably she was asked the same questions: Didn’t this place get broken into? Did they ever find his stuff? “And then I had to say, Yes and No.” The Yankees and Major League Baseball were able to replace most of the missing objects, so there are now 10 rings, though not the ones Berra actually wore on his fingers. There are replicas of the MVP trophies as well. But the sense of violation lingers. “They were his, they weren’t anybody else’s to take and destroy,” she says. Then she corrects herself: “You know what? As much as they were his, they were my family’s, they were mine, they were yours, they were Yankees fans’, and baseball fans’ everywhere, they were [for] the people who come in here just to learn about Grandpa Yogi’s life.”

It was strikingly similar to the sentiment voiced by the Maris family in North Dakota. And the family of golfer Art Wall in Scranton. And the folks at the Christy Mathewson exhibit. A day after the theft at the Boxing Hall of Fame, the local mayor held a press conference expressing “deep sadness” for the entire community. A radio station offered a reward. As one local said when interviewed about the theft by The New York Times: “The town is just beside itself. It’s a crime perpetrated against all of us.”

The endgame came gradually, then suddenly. And it had little to do with sports. Trotta says that by 2017, he was weary of his life of crime and all the lies it necessitated. He conceived of one, potentially final, high-risk, high-reward job. Sounding not unlike an aging boxer, he says, “It was going to be my last. Then I was going to retire.”

The wealthiest woman in the United States for most of her life, Marjorie Merriweather Post inherited her father’s cereal fortune and invested much of it in art and jewels. She died in 1973 and her estate was turned into an eponymous museum in Washington, D.C. Trotta made a series of scouting trips and set his sights on a jewel-studded coronation crown and “gold chalices from this czar.” Trotta figured he’d lift the crown—“we’re talking hundreds of diamonds worth millions”—sell the gems and get out of the game.

When Trotta finally entered the museum and prepared to smash its glass case with his axe, he heard the cat burglar’s most dreaded word.

“Freeze!”

A security guard Trotta hadn’t anticipated working the shift approached. Trotta didn’t freeze. He ran like hell and leapt out a window. But he didn’t grab the crown.

Trotta escaped. But standing so tantalizingly close to his biggest score—and, perhaps, his retirement—and failing to close? “It messed with me big-time,” says Trotta. He says he went through months of depression, replaying what went wrong. He increased his drinking. His marriage broke up. He returned to burglary—“gotta eat”—but lost interest in meticulous planning and exotic targets.

Then, the third act, so cliché it verges on inevitable: The thieves get sloppy. Back in Scranton, late one night in 2016, Trotta had stolen a snowplow, lassoed it to an ATM at the local ShopRite and hit the gas, uprooting the ATM and towing it away with him. He also never adjusted his m.o. for the explosion in surveillance technology or DNA technology.

On March 4, 2019, Trotta was driving erratically and was pulled over on Route 307 near Scranton. He not only failed the field sobriety test, but also his plates didn’t match his car. When police contacted the owner of the car, a cousin of Trotta’s, she granted permission to search the trunk. Police found a trove of evidence. A sledgehammer. A crowbar. An axe. Ski masks. Walkie-talkies. Stolen jewelry.

Most problematically, police found the pair of gloves Trotta had worn when he relieved the ShopRite of its ATM; gloves that had been caught on video. Trotta was taken to jail. When Joe D’Andrea, a prominent local defense lawyer, met with his newest client, he didn’t mince words. “Well, Tommy,” said D’Andrea, “they found everything but Jimmy Hoffa in your trunk.”

D’Andrea realized this case was going to metastasize quickly. There were open investigations throughout the country. Having cut himself in and on assorted windows and glass displays, Trotta had left copious amounts of plasma and DNA at numerous crime scenes.

D’Andrea says that when he “got a handle on the real depth of this,” he began to concoct a strategy. With a client willing to not only admit guilt but cooperate, D’Andrea took the rare step of reaching out to U.S. attorneys to initiate federal charges. This way, Trotta would face a consolidated prosecution from one federal jurisdiction, avoiding traipsing around the country from one court proceeding to the next.

It was over for Trotta. And he was relieved. Channeling Yogi Berra himself, Trotta says, “When it’s over, it’s over, you know?”

Starting in the spring of 2019, Trotta began serving a sentence—it would end up being 51 months—at a jail in Wilkes-Barre, 20 miles from Scranton. While Trotta is reluctant to comment on this point, he cooperated generously with law enforcement and, by multiple accounts, figured prominently as they built their case. He gave up his alleged co-conspirators, the getaway drivers, the lookouts, the gold-melters. The ringleader turned government witness. Last summer, the FBI held a press conference announcing that they had broken up “a major multistate theft ring” implicating nine people.

Five, including Trotta and his sister, entered guilty pleas. Four pleaded not guilty. (One went missing as a fugitive, before returning from months hiding in the woods and turning himself in earlier this year.) The indictment referenced everything from the art, to three antique firearms worth a combined $1 million, to $400,000 in gold nuggets stolen from a mining museum. And then there was the sports memorabilia. Belts. Plaques. World Series rings. And at least 33 separate trophies.

The vast majority of the stolen items were unrecovered, either melted down or, in the case of some artwork that couldn’t be fenced, burned. Trotta believes that the Mathewson jersey and the Pollock painting “are still out there.” He suggests they’re in a New Jersey stash that belongs to two of the alleged accomplices. But he says he has seen neither since his arrest. (Citing the open case and pending trials, U.S. attorneys declined to comment on the status of the missing items.)

Awaiting sentencing on a final federal charge of museum theft, Trotta went back to Scranton, trying to restart his life. He was back to working late at night, but it was legit: He landed a job in a restaurant supply warehouse. In May, however, he was found to have violated the terms of his pre-sentencing release and was ordered to report to prison.

Ideally, when he gets out, Trotta would like to work in security, putting his accumulated knowledge to good use. He’s aware of the reputational repair work that lies ahead. “It looks like I’m the biggest scumbag on Earth,” he says in his clipped Pennsylvania accent. “And I’m not. I am different now.”

He is particularly contrite about the Yogi Berra theft. “All the jobs were [of] historical significance, the importance of these items. But that one bothered me most out of all of them…. I’m so sorry.”

One state over in New Jersey, Lindsay Berra is still confronting her swirl of emotions. “You sell the stuff that you steal for pennies compared to what it’s actually worth?” she says, adding, “You’re destroying historical artifacts with significance so much beyond the gold and diamonds that they’re made of. It’s callous, and disrespectful, and dumb. I don’t get it.”

Asked whether her grandfather would have accepted Tommy Trotta’s apology, Lindsay Berra doesn’t hesitate. “He forgave George [Steinbrenner] after 14 years. Grandpa was such that if you owned up to your mistakes and you showed remorse, he would certainly forgive you.”

She thinks about her grandfather taking the high road—“It just kinda speaks to the way he lived his life and his humility”—and it provides comfort.

If there’s any gold in the story, maybe this is it.