Book Excerpt: Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale 1966 Million-Dollar Contract Holdout

Rogers Hornsby: “People ask me what I do in winter when there’s no baseball. I’ll tell you what I do. I stare out the window and wait for spring.”

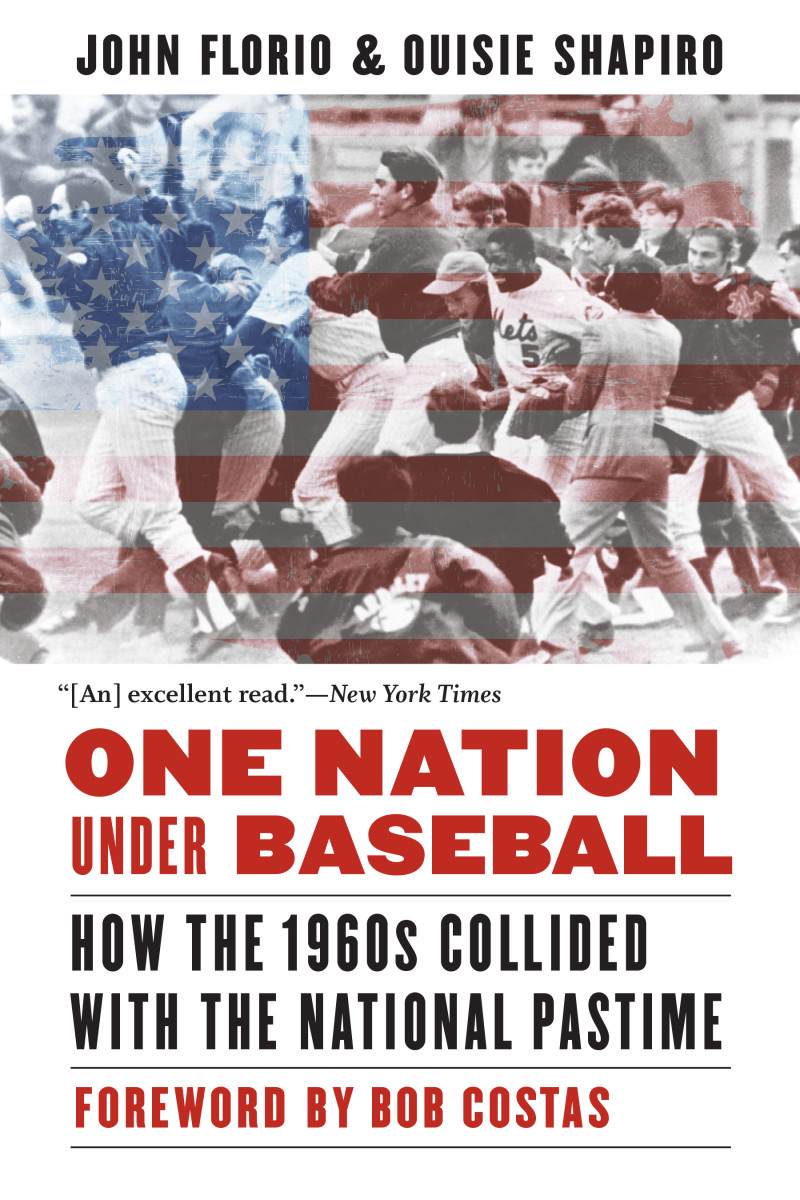

If we imagine Hornsby staring out the window, with no live steaming TV to watch and no online sellers to send books to his doorstep, we might just think, "hey, we don't have it so bad." Well, I don't know about you, but I'm getting my baseball fix by reaching for the bookshelf. And I can personally recommend this volume to you. It's "One Nation Under Baseball: How the 1960s Collided with the National Pastime" by John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro (April 2017, University of Nebraska Press, $9.99 Kindle, $14.64 paperback).

Florio describes the book this way:

"One Nation Under Baseball explores the intersection between American society and America’s pastime during the 1960s. It looks at the central issues -- race relations, the role of the press, and the labor wars between the players and the owners -- and reveals the events that reshaped the game.

"The decade was rich with memorable events. We spoke with insiders like Bill White and Elston Howard’s widow, Arlene, about the Jim Crow laws in Florida that segregated black players during spring training. Civil rights leader Andrew Young gave us a firsthand account of what it took for the city of Atlanta, determined to set itself apart from the backward South, to attract Henry Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves.

"We also look at the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK through the eyes of ballplayers who were deeply affected by the events. Mudcat Grant had met John Kennedy in 1960 and was devastated when he heard the news of Kennedy’s death. Bob Gibson reacted to Dr. King’s murder by channeling his fury onto opponents during the ’68 season. Don Drysdale, who’d had a personal connection to Robert Kennedy, took his death to heart.

"We also cover fascinating stories featuring lesser-known names. George Gmelch was a minor-league prospect for the Tigers when he was called to the draft board. Fearing deployment to Vietnam, he and two other players schemed to flunk their physicals. And Michael Feinberg, who as a teenager worked as a vendor at Shea Stadium, smoked pot with John Lennon in the dressing room before the Beatles went on stage.

"The bad boy of the decade, Jim Bouton, tells us how he threw the sport into chaos with baseball’s first tell-all. “Ball Four” shook the game to its core; no one was more shaken than Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who did his best to censor the book. Bouton’s recollection of his encounter with Kuhn the day he was summoned to the commissioner’s office is both hilarious and disturbing."

While the entire book is fascinating, we thought we'd whet Dodgers' fans appetites with Chapter 11, which focuses on the 1966 Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale million-dollar contract holdout. Trust me; savvy baseball fans, you will love this.

Read the entire chapter below:

In the winter following the 1965 World Series, Sandy Koufax met Don Drysdale and his wife, Ginger, at a Russian restaurant in the San Fernando Valley. The two pitchers, both twenty-nine, had become friendly when they went through basic training in Fort Dix, New Jersey, in the late ’50s. They hit it off, despite coming from wildly different backgrounds. The Brooklyn-born Koufax had attended the University of Cincinnati and taken night classes in architecture at Columbia University. He was studious and humble—and most comfortable at home, listening to classical music or reading. The blue-eyed Drysdale was a product of Van Nuys High School in Southern California; he looked as though he’d been plucked off a surfboard and was usually trailed by admiring teammates and hangers-on.

As heroes of the world championship Dodgers, Koufax and Drysdale were the toasts of LA. They’d won a combined forty-nine regular-season games, more than half the team’s total, and three more in the Series. Everyone knew the Dodgers would have been a middling bunch without them.

Which is why Koufax was so irritable at dinner.

He’d spent the morning in general manager Buzzie Bavasi’s office, negotiating his salary for the ’66 season. The meeting hadn’t gone well. Despite being a unanimous choice for the NL Cy Young award and taking World Series MVP honors, Koufax hadn’t been able to squeeze more than ninety-five thousand dollars out of Bavasi.

“You walk in there and give them a figure that you want to earn,” Koufax said to Drysdale. “And they tell you, ‘How come you want that much when Drysdale only wants this much?’”

The story irked Drysdale, mainly because Bavasi had pulled the same stunt on him, offering a mid-nineties salary and telling him Koufax was happy with less.

Bavasi had obviously been playing one pitcher against the other. Justifiable or not, he’d had his reasons. For starters, he prided himself on signing players for as little as possible. He also felt that starting pitchers were worth less than, say, shortstops, since starters worked every fourth day. Most important, though, was that Koufax and Drysdale were looking to top one hundred thousand dollars. Like all general managers, Bavasi saw that mark as an informal barrier, a glass ceiling that, once shattered for an elite athlete, would become meaningless when negotiating with lower-caliber players. The six-figure category was hallowed ground, strictly reserved for Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle.

Knowing Koufax and Drysdale had little choice but to sign, Bavasi hadn’t worried that he was screwing with box office gold, that his figures showed the two stars generating as much as six hundred thousand dollars in ticket sales. He also hadn’t concerned himself with another obvious truth: without the dynamic duo, the Dodgers wouldn’t have made it to the World Series, which turned out to be the most lucrative in history. The Dodgers and Twins had brought in nearly three million dollars from those seven games alone.

Ginger Drysdale listened as her husband and Koufax compared notes. Having worked as a model and an actress, and having been a member of the Screen Actors Guild, she couldn’t understand why ballplayers didn’t have agents. This wasn’t the first time the issue had come up. In 1962, when Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris made cameo appearances in the Hollywood movie Safe at Home, the film’s star Patricia Barry was surprised to learn that neither player had an agent. She casually mentioned as much to the Yankees’ general manager, Roy Hamey, who responded with an invective-laced diatribe.

In the case of Koufax and Drysdale, Ginger offered some unsolicited advice: “Why don’t you just walk in there and hold out together?”

A bell went off. Go in together? As a pair? Like a union? It had never been done before. But there was no denying it would give them more leverage.

According to Ginger, the two committed to a joint holdout right then and there.

“The only thing that was left for them to figure out was the representation,” she recalls. “Sandy had a business manager that was also an agent for some very big stars, and he suggested that J. William Hayes manage the negotiations for the both of them. So they made a pact that they were going to deal through this man only.”

The two pitchers met with Hayes, who recommended they go in with a package deal: $1 million for three years, or $166,666 per pitcher per year. Following Hayes’s advice, the pair walked into Bavasi’s office, together, and gave him their proposal. Then they told the GM that all negotiations would go through Hayes

Bavasi, no doubt thrown that he was suddenly dealing with a union, albeit a small one, reached for one of his most tried-and-true tactics. “Why don’t you head down to spring training?” he suggested. “We’ll straighten it out there.” But Koufax and Drysdale had made a pact—with Hayes, and with each other.

“Speak to Hayes,” they said.

Ginger remembers hearing about Bavasi’s reaction. “[The Dodgers] were absolutely shocked that Don and Sandy both said to the front office, ‘We’re not negotiating these contracts. We have an agent, and he will be handling our affairs.’ And at first, the front office took the position, ‘Well, we don’t talk to agents; you boys are gonna be out on the street because we just don’t operate that way.’ And so there was a long period of time that there was nothing said between the two parties.”

Eventually, though, Bavasi suggested the gang of two meet him at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Soon, the three were sitting at a table in the corner of the empty room, trying to settle on a number that would satisfy everybody.

Koufax scribbled a figure on a piece of paper. Bavasi took one look and grimaced.

Koufax tried again, this time lowering the total package price to $900,000, but Bavasi still scoffed at the number. He also made it clear that he wouldn’t agree to a multiyear deal and that he was through negotiating with Koufax and Drysdale as a unit.

The three left the hotel as they’d walked in: at a stalemate.

In the spring of 1966, nearly one out of every four American wage earners belonged to a union. That statistic included professional baseball players, even though their union was financed by the owners and came with virtually no bargaining power. It existed almost solely to run the pension fund.

Since the late 1800s, baseball players had tried, periodically, to organize themselves into an independent union—mainly to fight the reserve clause. But the courts had repeatedly sided with the league. It didn’t help the players that there were no rival leagues, no threats to dangle over an owner’s head. That is, until 1946—which is when outfielder Danny Gardella refused to re-up with the Giants, choosing instead to double his salary by joining the Mexican League.

When he returned to the States, Gardella found that no team would hire him, so he sued baseball for running what he argued was an illegal monopoly. His lawsuit raised the question, since teams were receiving income from radio and TV broadcasts, and doing business in several states, weren’t they subject to antitrust laws?

The league had little time for such distinctions.

Baseball officials badmouthed Gardella in the press. Branch Rickey called him a communist. But the league must have felt it was on shaky ground, because it settled with Gardella—and gave amnesty to any other players who’d joined the Mexican League. Moreover, to ward off any further rebellion, the owners had conceded to a minimum salary of five thousand dollars, a maximum pay cut of 25 percent, and a weekly spring training allowance of twenty-five dollars.

As the 1966 season was getting underway, many players were again growing dissatisfied, this time because their pension fund was malnourished. They’d seen too many retired players, broke and without any job prospects, scraping by on miniscule retirement checks.

According to the Uniform Player’s Contract, the owners were to contribute to the pension fund 60 percent of TV and radio revenue from the All-Star game and World Series, plus 60 percent of the box office receipts from the All-Star game. In 1966 that equation yielded $2.5 million, a paltry sum for a pension plan of that size. Still, the rumor mill was rife with speculation that the owners, particularly Walter O’Malley, were out to revise the agreement when it expired the following year. All indicators pointed toward TV revenue growing exponentially and the owners trying to freeze their payments by agreeing to a flat fee instead of a percentage-based figure. The deal would greatly benefit the owners.

A trio of veterans -- Robin Roberts, Jim Bunning, and Harvey Kuenn -- formed a search committee to find a new director for the Players Association, one that would help turn it into a bona fide union. Surprisingly, the committee’s biggest hurdle was the group it represented. The new executive director would have to be elected by the players, and many of them -- not to mention managers and coaches, who also had a vote -- came from the South. To them, “union” was a dirty word.

With that in mind, the committee’s first choice had been Robert Cannon, a Milwaukee district court judge who’d been serving as the Association’s de facto director for years, taking no pay, raising no ire, and championing no causes. While hardly an ideal choice, Cannon had one significant check in the plus column: he’d get votes from conservative players and the blessing of owners, who’d be signing his fifty-thousand-dollar paycheck. How could he not? He’d shown a decidedly hands-off approach, and if anything he had sided with management on most major disputes. John Galbreath, the owner of the Pirates, had been so keen on the candidate, he’d promised to include him in the players’ pension fund. But it turned out that Judge Cannon had no interest in leaving his courtroom, let alone moving his family to New York.

And so the committee turned to its second choice: a highly respected, mustached, silver-haired labor attorney named Marvin Miller.

Employee disputes had been in Miller’s blood for most of his forty-nine years. As a youngster in Brooklyn, he’d joined his father on the garment workers’ picket lines; he’d also watched his mother become one of the first members of the New York City teachers’ union. Miller had gone on to earn economics and law degrees from New York University, after which he’d spent sixteen years serving as the chief economist and contract negotiator for the United Steelworkers, a union of more than a million members.

Miller was largely responsible for turning the steelworkers into the biggest and most powerful industrial union in the country. To sell the staunchly pro-labor Miller to the players, Robin Roberts suggested bringing on former Republican vice president, Richard Nixon, as general counsel.

To Miller, the idea was practically laughable. He discussed the proposal in his book, A Whole Different Ball Game.

“Work shoulder to shoulder with Tricky Dick?” he wrote. “After twenty-five years in labor relations -- on the side of labor -- I could scarcely think of anyone I would have liked less to work with. . . . [He was] the neophyte congressional candidate from California who won election by slandering his opponent, Jerry Voorhis. I knew him as the senatorial candidate who weaseled into office using rotten Red Scare tactics against Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas . . . [as] a politician who consistently supported antiunion legislation.”

Miller told the committee that if Nixon was in, he was out; he called the politician an “owners’ man” with “no background whatsoever in representing employees and wouldn’t know the difference between a pension plan and a pitcher’s mound.” Besides, Miller had said, Nixon was already putting together a run at the presidency in 1968.

The owners, wanting no part of an agitator like Miller, proceeded to assault him with an unfettered smear campaign, painting him out to be a club-wielding labor boss, a headbanger straight out of On the Waterfront. Soon, a petition -- allegedly written by players -- appeared in the Herald Examiner. It read, “Our feeling is that [the new director of the Players Association] should have a legal background that the owners can respect. We have progressed a great deal in the past few years and we think this relationship between the owners and the players should continue.”

Miller ignored the attacks, as did the committee. Robin Roberts and his crew approved him, and Miller set out to gain votes by visiting all twenty spring training camps in Arizona and Florida.

“There were six hundred major league players. I could meet with and talk with every team,” Miller said to Major League Baseball years later. “That’s the essence of being an effective union president, to be able to communicate, and I don’t mean in writing. I mean to meet with one-on-one, and talk, and [share] ideas.”

By all accounts, Miller was an excellent listener, and what he heard in those meetings was that most players had no concept of trade unionism. He sought to point out that the steelworkers had used collective bargaining to improve wages and working conditions -- as the industry’s profits soared. But convincing pro ballplayers of what they could accomplish was a whole different matter.

“To my dismay,” Miller said, “when I started talking about the reserve clause, I found that players had been so brainwashed they had extreme doubts. I had players mouthing the management line -- that the owners would take their bats and balls and go home. It would be impossible to have competitive leagues.”

At one point, Miller had stood in the New York Yankees’ locker room, addressing the team and explaining why players had to get rid of the reserve clause. When he finished, Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton pulled him aside. Having attended a year and a half of college at Western Michigan University, Bouton had a deeper education than many players. He also had a keen interest in baseball’s labor situation.

Bouton questioned Miller about his vision. How could baseball work without a reserve clause? If players could move freely from team to team, wouldn’t the richest teams get the best players?

“You mean like the Yankees do now?” Miller asked him.

Bouton considered Miller’s response. For years, small-market teams like the Kansas City A’s had become, essentially, farm systems for the Yankees, often trading their best players for cash.

“I never thought about it like that,” Bouton said.

Miller recalled the conversation years later. “If one of the brightest players had been brainwashed to that extent, I knew that the task ahead was a very large one, indeed.”

When the time came to cast their ballots, players in Arizona’s Cactus League rejected Miller, 102–17. But in Florida’s Grapefruit League, where the rosters of the Dodgers, Cardinals, Phillies, Braves, Twins, and Pirates were fully integrated, Miller won a sweeping victory, 472–34.

“You now had a great many black and Latino players,” Miller told Counterpunch, looking back at that fateful spring. “You now had a much more diverse sampling of the American people than in the ’40s. You now had at least some people who were able to think in terms of what was wrong with the society, what was wrong with the conditions, people much more accustomed to thinking about these things.”

And so Miller became the first fulltime executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association. On day one he picked up the phone and called the owners to set a meeting. He didn’t expect the warmest of greetings, but he surely assumed his calls would be returned.

He was wrong.

While the Dodgers were working out in Vero Beach, Koufax and Drysdale were sitting at home, following the advice of J. William Hayes. They hadn’t shown up at spring training. They were being firm. They were ready to walk away.

For Koufax, the advice was easy to follow. He was making plenty in endorsements and had just signed to write his life story with author Ed Linn for a reported advance of $160,000. He also couldn’t stand the stronghold the owners had on players. This was his chance to even the score. Most important, though, was the deterioration of his arthritic elbow. There was little doubt that continuing to pitch would leave him permanently disabled. Even if he signed, the 1966 season would probably be his last.

The negotiations were tougher on Drysdale. He had plenty of life left on his arm and was just starting to raise a family. He was part-owner of a restaurant in Van Nuys, Don Drysdale’s Dugout, but as Ginger remembers it, “it was scary. We had just moved into a bigger house; we had expenses. We were two kids without a lot of investments because we were just learning how to operate in the big world.”

To make matters worse, all signs pointed to an extended holdout.

Walter O’Malley, by now accustomed to the role of Machiavelli, took his case to the press. “I admire the boys’ strategy, and we can’t do without them, even for a little while,” he said. “But we can’t give in to them. There are too many agents hanging around Hollywood looking for clients.”

Unlike O’Malley, Koufax and Drysdale stayed clear of the press. They held out in silence, surely aware of the stakes at hand. Thanks to their stratospheric seasons, they were in a position to fight for every player in the league. And the timing couldn’t have been better.

As Michael D’Antonio wrote in Forever Blue, his biography of O’Malley, “in California especially, the ’60s counterculture was in full bloom and it was hardly the time to stand in the way of anyone seeking to assert their rights.”

According to the New York Times, “Both Koufax and Drysdale . . . are amply aware of the economic implications of their negotiations, though they flatly refuse to talk about them. They know collective bargaining is anathema to baseball. They know that if they succeed in blowing the top off baseball pay scales the whole salary structure inevitably will rise. They know that the sort of hardnosed bargaining they are conducting is unknown to a sport in which the players have traditionally been the pawns.”

Players around the league were divided in their opinions of the holdout.

Leon Wagner, left fielder for the Cleveland Indians, said, “Fifty percent of [players] probably feel that [Koufax and Drysdale] are classing themselves as twenty times better than the average player and this hurts their pride. The other fifty percent feel the guys should get all they can. I make $35,000 a year. Koufax is good, all right, but I don’t think he’s a five-times better ballplayer than I am.”

The Yankees’ Elston Howard worried about the long-term impact of the holdout. “It could get out of hand,” he told the press. “I think the best method is the individual going in before management and bargaining his own salary.”

Vic Power, the onetime Yankees prospect who had recently retired from the Angels, said, “Never in my life have I been a holdout. I told all my general managers, ‘You pay me what you think I’m worth. If you think I’m worth ten cents, pay me ten cents -- but don’t expect me to play like a twenty-cent ballplayer.’”

As for the Dodgers, they were in full support of the striking pitchers, squashing any notion that they resented either one.

Reliever Ron Perranoski had been with the Dodgers since 1961. “Knowing Sandy the way I do,” he told the press, “I’m sure he’s concerned about what the rest of us think. I can tell him, though, we’re behind him one hundred percent. I hope he shows up, though. I’d hate to have to pitch 162 of those games by myself.”

Dodgers outfielder Lou Johnson was equally sympathetic. “I hope they get [the money]. I only wish I was in a position to negotiate like that. Us resent what they’re asking? Baloney. More power to them both. I’d love both of them to get what they want.”

One player, who spoke anonymously, was quoted as saying, “Anyone of us who’s resentful of what [Koufax] is asking ought to have his head examined. We ought to get down on our knees and thank him. He’s sticking his neck out for all of us. The way I understand it, he feels, ‘Why should the top baseball salary be arbitrarily set at $100,000?’ I know I’ll never get that much, or anywhere near that, but what Koufax is doing now is bound to help us all.”

What few players asked, but what Sports Illustrated wanted to know, was what made some players worth more than others.

The following is from the magazine during the stalemate: “What are Koufax and Drysdale worth to the Dodgers? In terms of standings, the Dodgers are world champs with them, second-division bums without them and their 49 wins. A second-division finish means at least a 300,000 attendance drop, and at $4.50 per fan that is a loss of $1.35 million. What’s more, Koufax draws an extra 10,000 fans when he pitches, and he starts twenty times at home. So there is another $900,000, making the total loss $2.25 million, not counting road receipts. Walter, give Buzzie the money.”

Koufax and Drysdale hoped O’Malley was reading. In the meantime, they stayed in shape -- Drysdale worked out at Pierce College in Los Angeles -- but they also started planning careers outside of baseball. They signed to act in a movie, Warning Shot, which was to star David Janssen, and they told Hayes to accept any offers that paid well. Hayes listened, lining up more television deals, plus an exhibition tour in Japan.

It was around this time that Hayes unearthed a state law making it illegal to extend personal service contracts in California beyond seven years. The result of a 1944 lawsuit brought by actress Olivia de Havilland against Warner Brothers, the law had been enacted to break the stranglehold Hollywood studios had on their actors and actresses. As Hayes saw it, the same law could be applied to the Koufax-Drysdale holdout.

He began preparing a lawsuit against the Dodgers. He kept his findings under wraps but did tell the press that if the two pitchers were to successfully challenge baseball’s reserve clause, they’d be “the Abraham Lincolns of the game.”

Someone, very possibly movie producer Mervin LeRoy, tipped off Walter O’Malley as to Hayes’s strategy --and softened the Dodgers’ stance.

On March 30, Chuck Connors, the star of TV’s hit show The Rifleman, and a onetime Dodgers prospect, stepped in and set up a meeting between Bavasi and the two pitchers.

Koufax was unable to attend, but Drysdale kept the appointment and met with Bavasi at Nikola’s, a restaurant near Dodger Stadium. They drank coffee and talked numbers. According to Drysdale, Bavasi agreed to pay him $115,000 and Koufax $125,000. Drysdale called Koufax on the phone and relayed the offer while Bavasi called O’Malley. Both came back to the table with a green light, ending a holdout that had lasted thirty-two days.

When the deal was announced to the press at Dodger Stadium, O’Malley immediately kicked into damage control, making it clear that the two pitchers were signed as individuals, not as a unit. They were being paid different salaries, he said. They were signed for one year, and they’d represented themselves. No agent.

Koufax kept the focus on baseball. “Thank god I don’t have to act in that movie,” he said.

He would never again act in any movie but would turn in another superb pitching performance. In 1966 he’d go 27-9 and lead the Dodgers to another pennant. He’d also take home his third Cy Young award, again by a unanimous vote.

As for Don Drysdale, the $115,000 pitcher would go 13-16 during the regular season and lose two games in the World Series.

The Dodgers would be swept by the Orioles in four games.

And Sandy Koufax, as he’d planned, would retire after the World Series, finally resting his blessed, arthritic elbow.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter.